Jesuit Beliefs About the Value of Institutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013 October

Volume 14, Issue 4 October, 2013 Coming Events In This Issue Oct Time Event Location Coming Events 1 3 6:30 PM CCMI & PLANNING MEETING KNIGHT'S HALL Grand Knight’s Report 2 4 4:00 PM FIRST FRIDAY CHAPEL CHAPEL 9 9:30 AM LADIES AUXILIARY MEETING KNIGHT'S HALL Rob Baker Golf Tourney 2 9 8:00 AM HOT DOG DAY VA HOSPITAL PARISH HALL Field Agent Report 3 10 6:00 PM VESPERS CHAPEL Deacon’s Teaching 4 10 7:00 PM KOC BUSINESS MTG KNIGHT'S HALL Council Officers 5 11 4:00 PM FALL FESTIVAL ST. ROSE Ladies Auxiliary Officers 5 12 10:00 AM FALL FESTIVAL ST. ROSE Council Chairmen/Directors 6 13 10:00 AM FALL FESTIVAL ST. ROSE Saints Alive 7 18 5:30 PM KOC SOCIAL KNIGHT'S HALL Soccer Challenge 11 17 7:00 PM KOC ASSEMBLY 2823 KNIGHT'S HALL Holiday Cheese Ball Order 12 25 5:30 PM KOC SOCIAL KNIGHT'S HALL 26 9:00 AM PARK AVE CLEAN-UP PARISH HALL Pro-life Personhood Amend 13 26 LADIES AUX CRAZY BINGO PARISH HALL 26 4:00 PM CORPORATE COMMUNION CHURCH Editor’s Note 27 November Newsletter It’s your newsletter. Officers and Articles Due committee chairmen are encouraged to submit articles. Anyone who would like to contribute an article please send it to 7027newsletter @gmail.com by the last Sunday of the month to be published in the fol- 2 lowing month’s newsletter. The Newsletter Editor 11 8 WWW.KofC7027.COM [email protected] Page 1 Volume 14, Issue 4 October, 2013 Grand Knight's Report Many believers long to spend daily time with God, praying and reading His Word. -

Archivum Historicum Societatis Iesu Table of Contents

VOL. LXXIX FASC. 158 JULY-DECEMBER 2010 ARCHIVUM HISTORICUM SOCIETATIS IESU Paul Oberholzer, S.J. Editor Advisory Editors Sibylle Appuhn-Radtke (Munich) Julius Oswald S.J. (Munich) Pau! Begheyn S.J. (Amsterdam) Antonella Romano (Florence) Robert L. Bireley SJ. (Chicago) Flavio Rurale (Udine) Louis Boisset SJ. (Rome) Lydia Salviucci Insolera (Rome) Francesco Cesareo (Worcester, Ma.) Klaus Schatz SJ. (Frankfurt/M) Rita Haub (Munich) Nicolas Standaert SJ. (Leuven) Jeffrey Klaiber SJ. (Lima) Antoni J. Oçerler SJ. (Oxford) Mark A Lewis SJ. (New Orleans) Agustin Udias SJ. (Madrid) Barbara Mahlmann-Bauer (Bern) TABLE OF CONTENTS Sif?yl!e Appuhn-Radtke, Ordensapologetik als Movens positivistischer Erkenntnis. Joseph Braun SJ. und die Barockforschung 299 Matthieu Bernhardt, Construction et enjeux du savoir ethnographique sur la Chine dans l'oeuvre de Matteo Ricci SJ. 321 Heinz Sprof~ Die Begriindung historischer Bildung aus dem Geist des Christlichen Humanismus der Societas Iesu 345 Cristiana Bigari, Andrea Pozzo S.J. e la sua eredità artistica. Antonio Colli da discepolo a collaboratore 381 Lydia Safviucci, Richard Biise~ Mostra su Andrea Pozzo SJ., pittore e architetto 407 Elisabetta Corsi, ''Ai crinali della storia". Matteo Ricci S.J. fra Roma e Pechino 414 Emanuele Colombo, Jesuits, Jews and Moslems 419 Pau/ Beghryn SJ., Bibliography 427 Book Reviews 549 Jesuit Historiographical Notes 591 Scientific activity of the members of IHSI 603 Index 606 BIBLIOGRAPHY ON THE HISTORY OF THE SOCIETY OF JESUS 2010 Paul Begheyn, S.J. I am grateful to the -

Ignatius, Prayer and the Spiritual Exercises

IGNATIUS, PRAYER AND THE SPIRITUAL EXERCISES Harvey D. Egan ECAUSE OF HIS EXTRAORDINARY apostolic success, and later that of B the order he founded, Ignatius’ reputation as one of the greatest mystics in the Christian tradition still remains somewhat obscured. When, years ago, I told a friend from a contemplative order that I was writing a book centred on Ignatius’ mysticism, he all but denied that Ignatius had a mystical side.1 Ignatius’ life, however, was profoundly affected by four foundational mystical events: his conversion experience while recovering at Loyola from the Pamplona battlefield injury; an experience of the Virgin Mary during that same recuperation which confirmed his desire to live a chaste life henceforth; the subsequent enlightenment at the River Cardoner; and his vision at La Storta leading him to a mysticism of service.2 In addition, God blessed him with numerous extraordinary secondary mystical phenomena. And one of the purest examples of the direct reporting of mystical experiences in Christian history can be found in Ignatius’ short Spiritual Diary. This extraordinary document contains irrefutable evidence of Ignatius’ deeply trinitarian, Christ-centred, Marian reverential love, and of the priestly, eucharistic and apostolic aspects of his mysticism. Also permeating it is a profoundly mystical emphasis on discernment, visions, intellectual and affective mystical events, somatic phenomena, mystical tears and mysterious loquela—a phenomenon consisting of different levels of inner words saturated with meaning, tones, rhythm and music. Bernard of Clairvaux, John of the Cross and others in the Christian tradition emphasized mystical bridal sleep—that is, swooning lovingly in God’s embrace at the centre of the soul—as the most valuable way of serving God, the Church and one’s neighbour. -

Ignatius, Prayer and the Spiritual Exercises 47–58 Harvey D

THE WAY a review of Christian spirituality published by the British Jesuits April 2021 Volume 60, Number 2 IGNATIUS AND THE FIRST COMPANIONS THE WAY April 2021 Foreword 5–6 Ignatius and the Stars 8–17 Tim McEvoy Ignatius of Loyola has a reputation as a hard-headed administrator, guiding and steering his nascent religious order from the heart of the Church in Rome. His personal writings, however, reveal other sides to his character. Here Tim McEvoy considers his predilection for gazing contemplatively at the stars, and asks what it can tell us about him in the light of the cosmology of his time. Ignatian Discernment and Thomistic Prudence: Opposition or 18–36 Harmony? Timothy M. Gallagher and David M. Gallagher Although Ignatius has become well known as a teacher of discernment, his methods have also attracted criticism at times. It has been suggested, for instance, that Ignatius’ thought lacks the precision to be found in the writings of Thomas Aquinas.Timothy and David Gallagher discuss how the Thomistic virtue of prudence might relate to, and supplement, Ignatian discernment. Core Ingredients in Ignatius' Recipe 37–45 Gail Paxman The well-known spiritual writer Anthony de Mello likened the text of the Spiritual Exercises to a cookery book. Here Gail Paxman develops that simile, exploring six of the ‘key ingredients’ in the Ignatian system, and looking at how they work together to produce the kind of conversion that is the goal of the Exercises themselves. Ignatius, Prayer and the Spiritual Exercises 47–58 Harvey D. Egan What is Ignatian prayer? His Spiritual Diary suggests that Ignatius himself spent long hours in mystical contemplation, yet he forbade his earliest followers to do the same. -

SJ Liturgical Calendar

SOCIETY OF JESUS PROPER CALENDAR JANUARY 3 THE MOST HOLY NAME OF JESUS, Titular Feast of the Society of Jesus Solemnity 19 Sts. John Ogilvie, Priest; Stephen Pongrácz, Melchior Grodziecki, Priests, and Mark of Križevci, Canon of Esztergom; Bl. Ignatius de Azevedo, Priest, and Companions; James Salès, Priest, and William Saultemouche, Religious, Martyrs FEBRUARY 4 St. John de Brito, Priest; Bl. Rudolph Acquaviva, Priest, and Companions, Martyrs 6 Sts. Paul Miki, Religious, and Companions; Bl. Charles Spinola, Sebastian Kimura, Priests, and Companions; Peter Kibe Kasui, Priest, and Companions, Martyrs Memorial 15 St. Claude La Colombière, Priest Memorial MARCH 19 ST. JOSEPH, SPOUSE OF THE BLESSED VIRGIN MARY, Patron Saint of the Society of Jesus Solemnity APRIL 22 THE BLESSED VIRGIN MARY, MOTHER OF THE SOCIETY OF JESUS Feast 27 St. Peter Canisius, Priest and Doctor of the Church Memorial MAY 4 St. José María Rubio, Priest 8 Bl. John Sullivan, Priest 16 St. Andrew Bobola, Priest and Martyr 24 Our Lady of the Way JUNE 8 St. James Berthieu, Priest and Martyr Memorial 9 St. Joseph de Anchieta, Priest 21 St. Aloysius Gonzaga, Religious Memorial JULY 2 Sts. Bernardine Realino, John Francis Régis and Francis Jerome; Bl. Julian Maunoir and Anthony Baldinucci, Priests 9 Sts. Leo Ignatius Mangin, Priest, Mary Zhu Wu and Companions, Martyrs Memorial 31 ST. IGNATIUS OF LOYOLA, Priest and Founder of the Society of Jesus Solemnity AUGUST 2 St. Peter Faber, Priest 18 St. Alberto Hurtado Cruchaga, Priest Memorial SEPTEMBER 2 Bl. James Bonnaud, Priest, and Companions; Joseph Imbert and John Nicolas Cordier, Priests; Thomas Sitjar, Priest, and Companions; John Fausti, Priest, and Companions, Martyrs 9 St. -

Jesuit Parish Report

A Jesuit Response to Laudato Si’ A Survey of Parishes in the Maryland & USA Northeast Jesuit Provinces on Parish-Sponsored Pastoral Initiatives, Education Programs, Arts Initiatives, Activities and Collaborations Inspired by Laudato Si’ September 2016 Colorful strips of paper containing students' handwritten commitments to protect the environment form an “Earth Ball” at St. Ignatius Church, Boston. Prepared by: Kate Tromble, Holy Trinity Parish Fran Dubrowski, Director, and Farley Lord Smith, Outreach Advisor, Honoring the Future® Suzanne Noonan, Volunteer, Honoring the Future® & Holy Trinity parish With guidance and support from: Fr. Edward Quinnan, SJ, Assistant for Pastoral Ministries, and Nicholas Napolitano, Assistant for Social Ministries, Maryland and USA Northeast Jesuit Provinces Introduction In response to Pope Francis’ 2015 encyclical, Laudato Si’: On the Care of Our Common Home, many parishes have actively discerned ways to respond to climate change and engaged in a variety of climate justice activities in their communities. The Maryland and USA Northeast Provinces invited Jesuit parishes to share their activities, actions, and resources in order to inform and inspire others. In partnership with Honoring the Future®, a nonprofit project which harnesses the power of art to educate, empower, and engage the public on climate change, the Provinces then compiled the parishes’ responses in this report. This report organizes parish responses into five main categories: Pastoral Initiatives, Education Programs, Arts Initiatives, Activities and Collaborations. This report also provides recommended resources from national Catholic and nonprofit organizations. We hope to inspire all parishes to respond to Laudato Si’ in their own unique way, offering these tangible eXamples and eXtensive resources as a starting point. -

Sacred Heart Catholic Church Sunday, October 27, 2019 30Th Sunday in Ordinary Time

SACRED HEART CATHOLIC CHURCH Sunday, October 27, 2019 30th Sunday in Ordinary Time All Saints Day Holy Day of Obligation Friday, November 1 9:00am Mass DAYLIGHT SAVINGS TIME ENDS NEXT WEEKEND, HAPPENINGS AT THE HEART SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 3RD! Remember to Set Your Clocks Back! David the King Presentation Sunday, October 27, 10:00am Bible Study Monday, October 28, 1:00pm Religious Ed. Monday, October 28, 6:00pm Tenderhearts Bible Study Wednesday, October 30, 7:00pm AA Meeting Thursday, October 31, 12:00 Noon All Saints Day Friday, November 1 Paul and Betty Nagy Holy Day of Obligation Masses 9:00am & 7:00pm AND Men’s Scripture Reflection Saturday, November 2, 7:30am Stephanie Bald and her AA Meeting Saturday, November 2, 8:00am daughter Adrianna Page 2 Sacred Heart Catholic Church HEARTS ON FIRE at Sacred Heart Where Faith is Known, Lived, & Shared OF THE WEEK I have come to set the earth on fire, and how 30th Week of Ordinary Time I wish it were already blazing. (Luke 12:49) On October 30, it is the feast day of St. Alphonsus Rodriguez, LISTEN to the Archbishop: GUIDEPOST 7 - who was born in Spain in 1531, of a well-to-do commercial FAMILIES; Marker 7.3: The Witness of Families household of Segovia, the third of 11 children. When Alphon- (cont.)—I encourage families who are living the sus was 11 years old, he and his older brother were sent to a Gospel to exercise radical generosity in inviting Jesuit college which had just been founded. He had already others to share in your family life, even if you are well manifested great joy in serving the Jesuits when they had given aware that it is not perfect. -

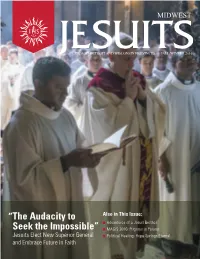

The Audacity to Seek the Impossible” “

MIDWEST CHICAGO-DETROIT AND WISCONSIN PROVINCES FALL/WINTER 2016 “The Audacity to Also in This Issue: n Adventures of a Jesuit Brother Seek the Impossible” n MAGIS 2016: Pilgrims in Poland Jesuits Elect New Superior General n Political Healing: Hope Springs Eternal and Embrace Future in Faith Dear Friends, What an extraordinary time it is to be part of the Jesuit mission! This October, we traveled to Rome with Jesuits from all over the world for the Society of Jesus’ 36th General Congregation (GC36). This historic meeting was the 36th time the global Society has come together since the first General Congregation in 1558, nearly two years after St. Ignatius died. General Congregations are always summoned upon the death or resignation of the Jesuits’ Superior General, and this year we came together to elect a Jesuit to succeed Fr. Adolfo Nicolás, SJ, who has faithfully served as Superior General since 2008. After prayerful consideration, we elected Fr. Arturo Sosa Abascal, SJ, a Jesuit priest from Venezuela. Father Sosa is warm, friendly, and down-to-earth, with a great sense of humor that puts people at ease. He has offered his many gifts to intellectual, educational, and social apostolates at all levels in service to the Gospel and the universal Church. One of his most impressive achievements came during his time as rector of la Universidad Católica del Táchira, where he helped the student body grow from 4,000 to 8,000 students and gave the university a strong social orientation to study border issues in Venezuela. The Jesuits in Venezuela have deep love and respect for Fr. -

Heaven's Heroes

October 2018 Missionary Childhood presents Saint of the Month: Heaven’s Heroes Saint Alphonsus Rodriguez, SJ October 30 Goal: To provide a lesson for children about a saint or saints who exemplify a deep relationship with God and the ability to share it with others Materials Needed: This lesson plan, accompanying story, and any necessary materials for follow up activities Objectives: 1. To assist children in developing the understanding that all of God's people are called to a life of holiness 2. To help children respond appropriately to the question: What is a saint? One who: • is proclaimed by the Church, after their death, to have lived a life of holiness • teaches others about Jesus by their example • lives like Jesus 3. To introduce one of our Church’s saints, Saint Alphonsus Rodriguez, SJ, telling as much of the story that you feel will interest the children at your grade level 4. To learn that Alphonsus was a saint because he lived in a way that respected the Gospel of Jesus 5. To learn that we are called by God to share the Gospel with our lives 6. To help the children develop listening skills Procedure: 1. Prepare the children to listen to Alphonsus’ story. 2. Read, or have read, the attached story of Saint Alphonsus. Elaborate or abbreviate as necessary for time constraints or age level of listeners. 3. Use the follow up questions (below). 4. Present follow-up activities below (optional). Any follow-up activity can be substituted. Saint Alphonsus Rodriguez, SJ Born in Spain in 1532, Alphonsus Rodriguez was the son of a wool merchant and his wife. -

Elizabeth Bayley Seton: Collected Writings, Volume Iiib #7

-655- Index Note: The documents 12.17 ("Elizabeth Seton's Day Book"), A-12.18 ("St. Joseph's Academy and Free School Roster 1809-1821"), and 12.25 (" 1812-1822 Receipt Book") are not included in the index. Each ofthese doc uments includes many names of students, merchants, and workers from the Emmitsburg area during the early years of the Sisters of Charity. A I Corinthians: 222, 236, 257, 300, 315, 584,587 Abelly, Rev. Louis: Elizabeth Seton's 2 Corinthians: 110 translation of biography of Vincent de Daniel: 89, 91, 92, 98 Paul, 217-354; citations of his work, 491 , David: 89 494,495,616 Ecclesiastes: 98 Adams, Rev. John: 635 Ephesians: 106, 340 Ann of Austria, Queen: 370 Elijah: 40 Astronomy: Elizabeth's interest in, 102 Exodus: 49, 54, 91, 96,100, 106,219 A vrillon, Jean Baptiste: 487, 616, 635 Ezechiel: 54, 106, 408 Galatians: 378 B Genesis: 25, 38, 90, 91, 96, 100, 101 ,238, Babade, Rev. Pierre, S.S.: inscription on a 240,295 painting, 593; references in letters, 619, Habakkuk: 63, 91 628; errata, 652 Holy Innocents: 26-27 Barreau, Jean: 492 Holy Spirit: 365 Barruel, Rev. Augustin: 475 Isaiah: 3, 89, 90, 91, 99, 105,263,264, Bayley, Guy Carleton (half-brother): 593 289, 302, 344 Bayley, Rev. James Roosevelt (nephew): 603, Jairus: 47 605 Jeremiah: 89,228, 295 Bayley, Dr. Richard (father): underlining in Job: 89, 97,101,102 Bibles of references to physicians, 92; Joel: 99, 244 636 John: 26, 35, 37, 43, 44, 54, 55, 68, 70, Bean, Sr. Scholastica: biographical note, as 75,89, 106,227,236,238, 239,305, incorporator of community, 117 310,319,322,324,325,345,355,389, Bennel, Sr. -

St Francis Xavier Church

A TOUR OF from these steps. Three weeks later, on April body and blood of Christ; and alpha and T RANCIS AVIER HURCH 7, 1882, a devastating fire gutted the interior omega, first and last letters of the Greek S F X C of the church, and destroyed the spire. alphabet, signifying God as the beginning Despite tremendous damage, the church was and end. The 2nd shows the Ten restored within a year, with the spire rebuilt Commandments and Holy Bible, the 3rd the by another Cincinnati architect, Samuel Greek IHS for Jesus, and the chi and rho for Hannaford. With the exception of two Christ; and again the alpha and omega. The windows behind the main altar the original 4th recalls the crucifixion: nails, hammer windows survived, although some are and pliers, and behind a Roman ax and whip obscured by the 20th century vestibule and the monogram “INRI”, Jesus of Nazareth, choir loft. Today this elaborately decorated King of the Jews. THE HISTORY building, notable for its pointed arches, The gray figures in the 5th are two WELCOME TO ST. XAVIER CHURCH! This spires, gargoyles, finials, and many marble symbols of the four Evangelists. The lion building, completed in 1861, is the third one altars, is considered the finest example of represents Mark and his gospel of on this site. The first Catholic church in Gothic Revival in Cincinnati. resurrection; Luke’s is the sacrificial ox Cincinnati, a little wooden structure built in In 1987 the interior furnishings were representing the priesthood of Christ. The 1819 at Liberty and Vine, was moved here on reconfigured to conform to changes called 6th shows the papal mitre and keys to rollers in 1821. -

Ignatian Prayer"

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/saintignatiusspe282veal i^n SIS ESS* HH 9k EffrMSWrn . 2vSSraT Zft&WM l(H dOC. .¥» t.V»* raffias HHT 4 u Saint Ignatius Speaks about "Ignatian Prayer" Joseph Veale, SJ. NEILL LIBRARY to t 28/2 MARCH 1996 ON COLLEGE THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY A group of Jesuits appointed from their provinces in the United States. The Seminar studies topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and practice of Jesuits, especially American Jesuits, and communicates the results to the members of the provinces. This is done in the spirit of Vatican II's recom- mendation that religious institutes recapture the original inspiration of their founders and adapt it to the circumstances of modern times. The Seminar wel- comes reactions or comments in regard to the material that it publishes. The Seminar focuses its direct attention on the life and work of the Jesuits of the United States. The issues treated may be common also to Jesuits of other regions, to other priests, religious, and laity, to both men and women. Hence, the studies, while meant especially for American Jesuits, are not exclu- sively for them. Others who may find them helpful are cordially welcome to read them. CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR George M. Anderson, S.J., is associate editor of America, in New York, and writes regularly on social issues and the faith (1993). Peter D. Byrne, S.J., is rector and president of St. Michael's Institute of Philoso- phy and Letters at Gonzaga University, Spokane, Wash. (1994).