Semiotext(E) Intervention Series 21 Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dialogic Linguistic Landscape of the Migrant and Refugee Camps in Calais, France

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Linguistics Linguistics 2016 Cries from The Jungle: The Dialogic Linguistic Landscape of the Migrant and Refugee Camps in Calais, France Jo Mackby University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.210 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Mackby, Jo, "Cries from The Jungle: The Dialogic Linguistic Landscape of the Migrant and Refugee Camps in Calais, France" (2016). Theses and Dissertations--Linguistics. 13. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/ltt_etds/13 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Linguistics at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Linguistics by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Occupy Wall Street: a Movement in the Making

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 5-20-2012 Occupy Wall Street: A Movement in the Making Hannah G. Kaneck Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the American Politics Commons, Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Economic Policy Commons, Education Policy Commons, Energy Policy Commons, Environmental Policy Commons, Health Policy Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, International Law Commons, Law and Gender Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Law Enforcement and Corrections Commons, Organizations Law Commons, Political Economy Commons, and the Social Policy Commons Recommended Citation Kaneck, Hannah G., "Occupy Wall Street: A Movement in the Making". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2012. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/245 Occupy Wall Street: a movement in the making Hannah Kaneck Spring 2012 1 Dedicated to my grandmother Jane Armstrong Special thanks to my parents Karrie and Mike Kaneck, my readers Stephen Valocchi and Sonia Cardenas, the Trinity College Human Rights Program, and to my siblings at Cleo of Alpha Chi 2 Table of Contents Timeline leading up to September 17, 2011 Occupation of Wall Street…………………….……………….4 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………..……………………………….….……..6 Where did they come from?...........................................................................................................7 -

Weathering the Legal Academy's Perfect Storm

The Paralegal American Association for Paralegal Education Volume 28, No. 2 WINTER 2013 The Future of Paralegal Programs in Turbulent Times: Weathering the Legal Academy’s Perfect Storm See article on page 21 AAFPE 33RD ANNUAL CONFERENCE Las Vegas/Summerlin See you in Las Vegas/ Summerlin, Nevada! The Paralegal American Association for Paralegal Education The Paralegal Educator is published two times a year by the American Association for Paralegal Education, OF CONTENTS 19 Mantua Road, Mt. Royal, New Jersey 08061. table (856) 423-2829 Fax: (856) 423-3420 E-mail: [email protected] PUBLICATION DATES: Spring/Summer and Fall/Winter Service Learning and Retention in the First Year 5 SUBSCRIPTION RATES: $50 per year; each AAfPE member receives one subscription as part of the membership benefit; additional member subscriptions The Annual Speed Mock Interview Meeting 9 available at the rate of $30 per year. ADVERTISING RATES: (856) 423-2829 The Perils of Unpaid Internships 12 EDITORIAL STAFF: Carolyn Bekhor, JD - Editor-in-Chief Julia Dunlap, Esq. - Chair, Publications Jennifer Gornicki, Esq. - Assistant Editor The Case for Paralegal Clubs 16 Nina Neal, Esq. - Assistant Editor Gene Terry, CAE - Executive Director Writing in Academia 19 PUBLISHER: American Association for Paralegal Education Articles and letters to the editor should be submitted to The Future of Paralegal Programs in Turbulent times: the Chair of the Publications Committee. Weathering the Legal Academy’s Perfect Storm 21 DEADLINES: January 31 and May 31. Articles may be on any paralegal education topic but, on occasion, a Paralegal Educator issue has a central Digital Badges: An Innovative Way to Recognizing Achievements 27 theme or motif, so submissions may be published in any issue at the discretion of the Editor and the Publications Committee. -

Occupy Wall Street: a Movement in the Making Hannah G

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Trinity College Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Works 5-20-2012 Occupy Wall Street: A Movement in the Making Hannah G. Kaneck Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Recommended Citation Kaneck, Hannah G., "Occupy Wall Street: A Movement in the Making". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2012. Trinity College Digital Repository, http://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/245 Occupy Wall Street: a movement in the making Hannah Kaneck Spring 2012 1 Dedicated to my grandmother Jane Armstrong Special thanks to my parents Karrie and Mike Kaneck, my readers Stephen Valocchi and Sonia Cardenas, the Trinity College Human Rights Program, and to my siblings at Cleo of Alpha Chi 2 Table of Contents Timeline leading up to September 17, 2011 Occupation of Wall Street…………………….……………….4 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………..……………………………….….……..6 Where did they come from?...........................................................................................................7 New York, NY: A History of Occupation……………………………………………………………………………………..8 Talking Shop and Jamming Hard: Adbusters roots…………………………………………………………………..11 Inspiration is Just around the Corner: Bloombergville……………………………………………………………..16 The Devil’s in the Details: Organizing through Direct Democracy………….……………………………......17 The Occupation…………..…………………………………………………………………………….…………………………….18 -

American Studies Newsletter

American Studies Volume 9, Issue 1 Summer 2012 Newsletter American Studies Ph.D. Graduates 2011 -2012 Inside this issue: During the 2011-2012 academic year, the American Studies program at Purdue University conferred seven doctoral degrees to students from diverse academic backgrounds. Mark Bousquet, who con- 2011 ASA ANNUAL 2 centrated in English, successfully defended his dissertation entitled, MEETING “Driftin’; Round the World in a Blubber Hunter”: Nineteenth-Century 2012 PURDUE 3 American Whaling Narratives.” Currently, he is the Assistant Director AMST SYMPOSIUM of Core Writing at the University of Nevada-Reno. In June 2012, Bousquet published another book of fiction entitled, Gunfighter 2011-2012 ASGSO YR. 4 IN REVIEW Gothic Volume 0: Blood of the Universe. Recent Ph.D. graduate, Phi- lathia Bolton, will serve as a lecturer in English during the forth- MEET THE NEW 5 STUDENTS (2011) coming academic year. Her dissertation was entitled, “Making Dead and Barren”: Black Women Writers on the Civil Rights Movement and the APAC 5 Problem of the American Dream. ANNOUNCEMENT Recent Ph.D. graduate: Another Ph.D. graduate, Jamie Hickner, successfully defended Philathia Bolton COMMUNITY 6 her dissertation in the fall of 2011. Hickner’s dissertation entitled, ENGAGEMENT “History Will One Day Have Its Say”: Patrice Lumumba and the Black Freedom Movement, built upon her 2011 EISINGER 7 lengthy research and study on this Congolese independence leader during her time here at Purdue. SPOTLIGHT During the same semester (and in the same week), Charles Park defended his dissertation which was entitled, “Between a Myth and a Dream”: The Model Minority Myth, the American Dream, and Asian Americans 2011-2012 WALLA 8 in Consumer Culture. -

1 United States District Court for the District Of

Case 1:13-cv-00595-RMC Document 18 Filed 03/12/14 Page 1 of 31 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ) RYAN NOAH SHAPIRO, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 13-595 (RMC) ) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, ) ) Defendant. ) ) OPINION Ryan Noah Shapiro sues the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), 5 U.S.C. § 552, and the Privacy Act (PA), 5 U.S.C. § 552a, to compel the release of records concerning “Occupy Houston,” an offshoot of the protest movement and New York City encampment known as “Occupy Wall Street.” Mr. Shapiro seeks FBI records regarding Occupy Houston generally and an alleged plot by unidentified actors to assassinate the leaders of Occupy Houston. FBI has moved to dismiss or for summary judgment.1 The Motion will be granted in part and denied in part. I. FACTS Ryan Noah Shapiro is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Science, Technology, and Society at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Compl. [Dkt. 1] ¶ 2. In early 2013, Mr. Shapiro sent three FOIA/PA requests to FBI for records concerning Occupy Houston, a group of protesters in Houston, Texas, affiliated with the Occupy Wall Street protest movement that began in New York City on September 17, 2011. Id. ¶¶ 8-13. Mr. Shapiro 1 FBI is a component of the Department of Justice (DOJ). While DOJ is the proper defendant in the instant litigation, the only records at issue here are FBI records. For ease of reference, this Opinion refers to FBI as Defendant. 1 Case 1:13-cv-00595-RMC Document 18 Filed 03/12/14 Page 2 of 31 explained that his “research and analytical expertise . -

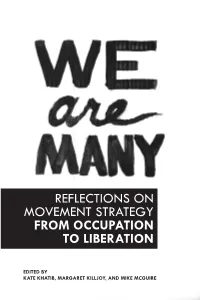

Reflections on Movement Strategy from Occupation to Liberation

REFLECTIONS ON MOVEMENT STRATEGY FROM OCCUPATION TO LIBERATION EDITED BY KATE KHATIB, MARGARET KILLJOY, AND MIKE MCGUIRE We Are Many: Reflections on Movement Strategy From Occupation to Liberation Edited by Kate Khatib, Margaret Killjoy, and Mike McGuire All essays © 2012 by their respective authors. This edition © 2012 AK Press (Oakland, Edinburgh, Baltimore) ISBN: 978-1-84935-116-4 | e-ISBN: 978-1-84935-117-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2012914345 AK Press AK Press 674-A 23rd Street PO Box 12766 Oakland, CA 94612 Edinburgh, EH8 9YE USA Scotland www.akpress.org www.akuk.com [email protected] [email protected] The above addresses would be delighted to provide you with the latest AK Press distribution catalog, which features the several thousand books, pamphlets, zines, audio and video products, and stylish apparel published and/or distributed by AK Press. Alternatively, visit our websites for the complete catalog, latest news, and secure ordering. Visit us at: www.akpress.org | www.akuk.com | www.revolutionbythebook.akpress.org Printed in the USA on acid-free, recycled paper. Cover and interior design by Margaret Killjoy | www.birdsbeforethestorm.net Cover image based on a sign painted by Erin Barry-Dutro The images on the following pages are licensed Creative Commons - Attribution 3.0: 38, 150, 162, 204, 216, 238, 314, 336, 350, 360, 372 The images on the following pages are licensed Creative Commons - Attribution - Share-alike 3.0: 122, 254, 416 The images on the following pages are licensed Creative Commons - Attribution - Noderivs 3.0: 74 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: Kate Khatib . -

Occuprint Portfolio Occuprint, Roger Peet, Favianna Rodriguez, Art Hazelwood, Josh Macphee, Lmnopi

OCCUPRINT PORTFOLIO OCCUPRINT, ROGER PEET, FAVIANNA RODRIGUEZ, ART HAZELWOOD, JOSH MACPHEE, LMNOPI Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Occuprint Medium: silkscreen, letterpress Binding: loose pages Dimensions: Pages: 31 Edition Size: 100 Origin Description: “Occuprint emerged when The Occupied Wall Street Journal asked us to guest curate an issue dedicated to the poster art of the global Occupy movement. The Occuprint website is meant to connect people with this work, and provide a base of support for print-related media within the #Occupy movement. http://occuprint.org/ “Occuprint showcases posters from the worldwide Occupy movement, all of which are part of the creative commons, and available to be downloaded for noncommercial use, though we ask that artists be given attribution for their work. Our Print Lab is collaboration with the Occupy Wall Street Screen Printing Guild. The OWS Screen Printing Guild is an official working group within the OWS General Assembly. It is an open working group that regularly incorporates new members into its process and can be contacted at owsscreenguild(at)gmail(dot)com. “We look forward to creating and distributing more printed matter by supporting the development of screen-printing labs at other locations worldwide, and by printing more of the wonderful posters that we are receiving.” —Occuprint The silkscreen portfolio has thirty-one 12” x 18” hand silk-screened artists’ prints on French paper in an archival silk-screened presentation folder. This project was designed and curated by Occuprint organizer, Jesse Goldstein, various Occuprint editorial committee members (including Molly Fair, Josh MacPhee, and John Boy) and Booklyn's Directing Curator Marshall Weber. -

Occupy Online 10 24 2011

Occupy Online: Facebook and the Spread of Occupy Wall Street Neal Caren [email protected] Sarah Gaby [email protected] University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill October 24, 2011 Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1943168 Occupy Online: Facebook and the Spread of Occupy Wall Street Summary Since Occupy Wall Street began in New York City on September 17th, the movement has spread offline to hundreds of locations around the globe. Social networking sites have been critical for linking potential supporters and distributing information. In addition to Facebook pages on the Wall Street Occupation, more than 400 unique pages have been established in order to spread the movement across the US, including at least one page in each of the 50 states. These Facebook pages facilitate the creation of local encampments and the organization of protests and marches to oppose the existing economic and political system. Based on data acquired from Facebook, we find that Occupy groups have recruited over 170,000 active Facebook users and more than 1.4 million “likes” in support of Occupations. By October 22, Facebook pages related to the Wall Street Occupation had accumulated more than 390,000 “likes”, while almost twice that number, more than 770,000, have been expressed for the 324 local sites. Most new Occupation pages were started between September 23th and October 5th. On October 11th, occupy activity on Facebook peaked with 73,812 posts and comments to an occupy page in a day. By October 22nd, there had been 1,170,626 total posts or comments associated with Occupation pages. -

INSIDE Country

WatchdogThe t h e m r c ’ s m o n t h l y m e m b e r s ’ r e p o r t CREATING A MEDIA CULTURE IN AMERICA WHERE TRUTH AND LIBERTY FLOURISH Vol. 18 • Issue 12 • December 2011 Liberal Media Ignore Deaths, Violence, and Anti-Semitism at ‘Occupy’ Protests To Protect Obama and Left-Wing Agenda The liberal media, particularly the to other cities. By Nov. 10 there were big guns ABC, CBS, NBC, and CNN are more than 2,700 arrests at Occupy sites MRC Headquarters • Alexandria, Va refusing to report on the widespread nationwide. In addition, there were and deadly violence occurring at many at least 75 incidents of sexual assault, “Occupy Wall Street” protests across the violence, vandalism, drug dealing, INSIDE country. When they do say something public nudity, public masturbation, and about the violence, it is usually brief anti-Semitism. One protestor defecated PAGE 3 and downplayed. on a police car. 20 Reasons to End That’s liberal bias by By Nov. 13 at least Public Broadcasting’s omission: not reporting three people had been $460-Million Gravy Train something to protect killed: One young man PAGE 4 or advance a left-wing was shot to death at Bits & Pieces: agenda. We are con- Occupy Oakland; in City Michael Moore B.S., tinuing to document, Hill Park in Burlington, What’s He Benn Drinking? expose, and neutralize Vt., a veteran shot him- Commie Comment, that bias through our self in the head; and at Democrat? various divisions at the At Occupy Wall Street, MRC TV Occupy Salt Lake City a ABC, CBS, NBC: Shh! Media Research Center. -

December 21, 2011 MINUTES

4211 BOARD OF ESTIMATES December 21, 2011 MINUTES REGULAR MEETING Honorable Bernard C. “Jack” Young, President Honorable Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, Mayor Honorable Joan M. Pratt, Comptroller and Secretary George A. Nilson, City Solicitor Alfred H. Foxx, Director of Public Works David E. Ralph, Deputy City Solicitor Ben Meli, Deputy Director of Public Works Bernice H. Taylor, Deputy Comptroller and Clerk * * * * * * * * The meeting was called to order by the President. * * * * * * * * President: “I will direct the Board members attention to the memorandum from my office dated December 19, 2011, identifying matters to be considered as routine agenda items, together with any corrections and additions that have been noted by the Deputy Comptroller. I will entertain a motion to approve all of the items contained on the routine agenda.” City Solicitor: “Move the approval of all items on the routine agenda.” Comptroller: “Second.” President: “All those in favor say ‘AYE’. Those opposed ‘NAY’. The routine agenda has been adopted.” * * * * * * * * 4212 BOARD OF ESTIMATES 12/21/2011 MINUTES BOARDS AND COMMISSIONS 1. Prequalification of Contractors In accordance with the Rules for Qualification of Contractors, as amended by the Board on October 30, 1991, the following contractors are recommended: Adams-Robinson Enterprises, Inc. $ 84,708,000.00 Baltimore Pile Driving & Marine $ 7,992,000.00 Construction, Inc. Cossentino Contracting Company, Inc. $ 8,000,000.00 Goel Services, Inc. $ 40,563,000.00 Hempt Bros, Inc. $ 38,466,000.00 Kokosing Construction Company, Inc. $510,966,000.00 MWH Constructors, Inc. and $139,608,000.00 Subsidiaries Morgan-Keller, Inc. $ 61,677,000.00 Reglas Painting Co., Inc. -

AFL-CIO Young Worker Groups Research Project

AFL-CIO YOung WOrker grOups reseArCh prOjeCt Prepared by: Monica Bielski Boris (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign), David Reynolds (Wayne State University) and Todd Dickey, Jeff Grabelsky and Ken Margolies (Cornell University), under the auspices of The Worker Institute at Cornell University preface At the quadrennial AFL-CIO Convention in 2009, AFL-CIO delegates committed to growing and strengthening the labor movement by passing Resolution 55, “In Support of the AFL-CIO Programs for Young Workers.” Out of that, the Next Up Young Worker Program was born, with the goals of engaging, empowering and mobilizing union members and nonunion workers under the age of 35. Since then, the young worker program has hosted two national summits, established a Young Worker Advisory Council and helped launch dozens of young worker groups at the local level. In an effort to support this work, the AFL-CIO commissioned “The Young Worker Groups Research Project.” This study looked at eight different young worker groups—and their respective leadership—to better understand and support the development of young worker groups within state federations, area labor federations and central labor councils. By gleaning the best practices and looking at the challenges of existing young worker groups, this study can be used as a tool and as a resource for labor leaders who want to establish their own young worker programs. Thanks to the work of a research team assembled by the new Worker Institute at Cornell that included labor educators from Cornell University, University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign and Wayne State University, we now have a useful tool for developing and supporting young workers.