Doomed to Re-Repeat History: the Triangle Fire, the World Trade Center Attack, and the Importance of Strong Building Codes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Skål USA Executive Committee - Monthly Conference Call Meeting Agenda Monday, April 5Th, 2021 4:00PM EDT

Skål USA Executive Committee - Monthly Conference Call Meeting Agenda Monday, April 5th, 2021 4:00PM EDT Type of Meeting: Monthly Conference Call Call-in mode: Go-to-Meeting hosted by ABA Meeting Facilitator: Jim Dwyer, President Invitees: Skål USA Executive Committee ______________________________________________________________________________ PLEASE DO NOT USE SPEAKERPHONES. IF USING YOUR COMPUTER PLEASE USE HEADPHONES. Call to Order - President Jim Dwyer Roll Call – Richard Scinta President’s Update – Jim Dwyer • Approval of Consent Agenda 1. President’s Written Report – Jim Dwyer 2. March (Feb Month end) Financial Report – Art Allis 3. VP Administrator’s Written Report – Richard Scinta 4. IS Councilor’s Written report – Holly Powers 5. VP Membership’s Written report – Tom Moulton 6. VP of PR & Communication’s Written report – Pam Davis 7. Directors of Membership’s Written reports (2) – Morgan Maravich & Mark Irgang • Skal Canada Website – Team Discussion • Streamyard EC Ratification • Bylaws and Articles of Incorporation Modifications - Holly • Articles of Incorporation Review – Holly and Richard International Skål Councilor – Holly Powers Financial Report – Art Allis Administration Update – Richard Scinta • Philanthropic Events VP Membership – Tom Moulton • New Career Center Discussion – New Benefit Approval Director Membership – Morgan Maravich Mark Irgang VP Communications – Pam Davis Next Meeting: Monday, May 3rd, 2021 4:00 PM EST Skal USA President Report March 2021 Einstein “the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result Dwyer “Negativity is the cornerstone of failure” Meetings and Zooms • International Skål Zoom with Skål Miami and Skal Sydney • International Zoom with Skal Mexico and proposed the twinning of Skal Mexico City and Skal New Jersey which may take place on May 5. -

Winter League AL Player List

American League Player List: 2020-21 Winter Game Pitchers 1988 IP ERA 1989 IP ERA 1990 IP ERA 1991 IP ERA 1 Dave Stewart R 276 3.23 258 3.32 267 2.56 226 5.18 2 Roger Clemens R 264 2.93 253 3.13 228 1.93 271 2.62 3 Mark Langston L 261 3.34 250 2.74 223 4.40 246 3.00 4 Bob Welch R 245 3.64 210 3.00 238 2.95 220 4.58 5 Jack Morris R 235 3.94 170 4.86 250 4.51 247 3.43 6 Mike Moore R 229 3.78 242 2.61 199 4.65 210 2.96 7 Greg Swindell L 242 3.20 184 3.37 215 4.40 238 3.48 8 Tom Candiotti R 217 3.28 206 3.10 202 3.65 238 2.65 9 Chuck Finley L 194 4.17 200 2.57 236 2.40 227 3.80 10 Mike Boddicker R 236 3.39 212 4.00 228 3.36 181 4.08 11 Bret Saberhagen R 261 3.80 262 2.16 135 3.27 196 3.07 12 Charlie Hough R 252 3.32 182 4.35 219 4.07 199 4.02 13 Nolan Ryan R 220 3.52 239 3.20 204 3.44 173 2.91 14 Frank Tanana L 203 4.21 224 3.58 176 5.31 217 3.77 15 Charlie Leibrandt L 243 3.19 161 5.14 162 3.16 230 3.49 16 Walt Terrell R 206 3.97 206 4.49 158 5.24 219 4.24 17 Chris Bosio R 182 3.36 235 2.95 133 4.00 205 3.25 18 Mark Gubicza R 270 2.70 255 3.04 94 4.50 133 5.68 19 Bud Black L 81 5.00 222 3.36 207 3.57 214 3.99 20 Allan Anderson L 202 2.45 197 3.80 189 4.53 134 4.96 21 Melido Perez R 197 3.79 183 5.01 197 4.61 136 3.12 22 Jimmy Key L 131 3.29 216 3.88 155 4.25 209 3.05 23 Kirk McCaskill R 146 4.31 212 2.93 174 3.25 178 4.26 24 Dave Stieb R 207 3.04 207 3.35 209 2.93 60 3.17 25 Bobby Witt R 174 3.92 194 5.14 222 3.36 89 6.09 26 Brian Holman R 100 3.23 191 3.67 190 4.03 195 3.69 27 Andy Hawkins R 218 3.35 208 4.80 158 5.37 90 5.52 28 Todd Stottlemyre -

TM 3.1 Inventory of Affected Businesses

N E W Y O R K M E T R O P O L I T A N T R A N S P O R T A T I O N C O U N C I L D E M O G R A P H I C A N D S O C I O E C O N O M I C F O R E C A S T I N G POST SEPTEMBER 11TH IMPACTS T E C H N I C A L M E M O R A N D U M NO. 3.1 INVENTORY OF AFFECTED BUSINESSES: THEIR CHARACTERISTICS AND AFTERMATH This study is funded by a matching grant from the Federal Highway Administration, under NYSDOT PIN PT 1949911. PRIME CONSULTANT: URBANOMICS 115 5TH AVENUE 3RD FLOOR NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10003 The preparation of this report was financed in part through funds from the Federal Highway Administration and FTA. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The contents of this report reflect the views of the author who is responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do no necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the Federal Highway Administration, FTA, nor of the New York Metropolitan Transportation Council. This report does not constitute a standard, specification or regulation. T E C H N I C A L M E M O R A N D U M NO. -

Frise Historique

Construction on the north tower The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey began began. obtaining property at the World Trade Center site. 01/08/1968 01/03/1965 Demolition at the site began with the clearance of thirteen square blocks of low rise buildings for construction of the Minoru Yamasaki, The The Port Authority chose the current site for the World Trade World Trade Center. architect of the World Center. 01/01/1966 Trade Center. 20/09/1962 1960 Minoru Yamasaki was selected to design the project. He was a second generation Groundbreaking for the construction began on Japanese-American who studied architecture at the August 5, 1966. Site preparations were vast and University of Washington and New York University. included an elaborate method of foundation work Construction of He considered hundreds of different building for which a "bathtub" had to be built 65 feet configurations before deciding on the twin towers below grade. The bathtub was made of a bentonite the south tower design. The Port Authority unveiled the $525 million (absorbent clay) slurry wall intended to keep out World Trade Center plan to the public. It was a groundwater and the Hudson River. began. composite of six buildings comprised of 10 million Yamasaki's design for the World Trade square feet of office space. At its core were the Twin Center was unveiled to the public. 01/01/1969 Towers, which at 110 stories (1,368 and 1,362 feet) The design consisted of a square plan each would be the world's tallest skyscrapers. approximately 207 feet in dimension on each side. -

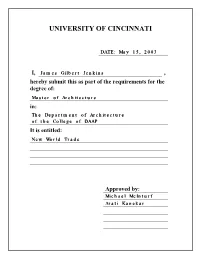

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI DATE: May 15, 2003 I, James Gilbert Jenkins , hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Architecture in: The Department of Architecture of the College of DAAP It is entitled: New World Trade Approved by: Michael McInturf Arati Kanekar NEW WORLD TRADE A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE In the Department of Architecture Of the College of Design, Art, Architecture, and Planing 2003 by James G. Jenkins B.S., University of Cincinnati, 2001 Committee Chair : Michael Mcinturf Abstract In these Modern Times, “facts” and “proofs” seem necessary for achieving any credibility in a field where there is a client. To arrive at a “truth,” many architects quickly turn to a dictionary for the final “truth” of a word, such as “privacy” or to a road map to find the “truth” in site conditions, or to a census count for the “truth” of people migration. It is, of coarse, part of the Modern Crisis that many feel the need to go with the way of technology, for fear that Architecture might otherwise fall by the wayside because of its perceived irrelevancy or frivolousness. Following this action, with time, could very well reduce Architecture to a form of methodology and inevitably end with the replacement or removal of the profession from its importance- as creators of a “Truth.” The following thesis is a serious reclamation. The body of work moves to take back for Architecture its power, and specifically it holds up and praises the most important thing we have, but in modern times have been giving away: Life. -

SEPTEMBER 11Th: ART LOSS, DAMAGE, and REPERCUSSIONS Proceedings of an IFAR Symposium

International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR) www.ifar.org This article may not be published or printed elsewhere without the express permission of IFAR. SEPTEMBER 11th: ART LOSS, DAMAGE, AND REPERCUSSIONS Proceedings of an IFAR Symposium SPEAKERS • Saul S. Wenegrat: Art Consultant; Former • Dietrich von Frank: President and CEO, AXA Art Director, Art Program, Port Authority of NY and NJ Insurance Corporation • Elyn Zimmerman: Sculptor (World Trade Center • Gregory J. Smith: Insurance Adjuster; Director, Memorial, 1993) Cunningham Lindsey International • Moukhtar Kocache: Director, Visual and Media Arts, • John Haworth: Director, George Gustav Heye Center, Lower Manhattan Cultural Council Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian • Suzanne F.W. Lemakis: Vice President and Art • Lawrence L. Reger: President, Heritage Preservation, Curator, Citigroup Heritage Emergency National Task Force IFAR SYMPOSIUM: THE ART LOST & DAMAGED ON 9/11 INTRODUCTION SHARON FLESCHER* Five months have passed since the horrific day in September that took so many lives and destroyed our sense of invulner- ability, if we were ever foolish enough to have had it in the first place. In the immediate aftermath, all we could think about was the incredible loss of life, but as we now know, there was also extensive loss of art—an estimated $100 mil- lion loss in public art and an untold amount in private and corporate collections. In addition, the tragedy impacted the art world in myriad other ways, from the precipitous drop in museum attendance, to the dislocation of downtown artists’ Left to right: Sharon Flescher, Saul S. Wenegrat, Elyn studios and arts organizations, to the decrease in philan- Zimmerman, Moukhtar Kocache, and Suzanne F. -

Photographs of Falling Bodies and the Ethics of Vulnerability in Jonathan Safran Foer’S Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close Chris Vanderwees

Photographs of Falling Bodies and the Ethics of Vulnerability in Jonathan Safran Foer’s Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close Chris Vanderwees Abstract: The article explores the ethical and political relationship between Jonathan Safran Foer’s Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close and the photographs of those who fell (or leapt) from the World Trade Center on 11 September 2001. Drawing on Judith Butler’s theorization of the ethics of vulnerability, the article briefly outlines ongoing debates around the photography of atrocity in order to suggest that rather than reaffirm tropes of American exceptionalism and victory culture in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, Foer’s novel and its engagement with the falling body may prompt readers to consider ethical recognition and responsibility to others. Keywords: Jonathan Safran Foer, Judith Butler, September 11 terrorist at- tacks, photography, visual culture, ethics, trauma Re´sume´ : Cet article explore la relation e´thique et politique entre le roman Extreˆmement fort et incroyablement pre`s de Jonathan Safran Foer et les photo- graphies des personnes qui sont tombe´es (ou se sont jete´es) du World Trade Center, le 11 septembre 2001. S’inspirant de l’e´thique de la vulne´r- abilite´ telle qu’elle est the´orise´e par Judith Butler, l’article e´voque brie`ve- ment le de´bat re´current sur la photographie de l’atroce pour sugge´rer que le roman de Foer, dans son rapport e´troit au corps qui chute, ne renforcer- ait pas ne´cessairement, dans le sillage des attentats du 11 septembre, les lieux communs sur l’exceptionnalisme e´tatsunien et la culture de la vic- toire, mais inciterait plutoˆt les lecteurs a` re´fle´chir a` une e´thique de la reconnaissance et a` la responsabilite´ envers autrui. -

DH&S New York Celebrates Move to World Trade Center

University of Mississippi eGrove Haskins and Sells Publications Deloitte Collection 1981 DH&S New York celebrates move to World Trade Center Anonymous Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/dl_hs Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation DH&S Reports, Vol. 18, (1981 no. 1), p. 21-28 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Deloitte Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Haskins and Sells Publications by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. t was with panache and a distinctive Big Apple flair that the New York Ioffice formally celebrated its relo- cation to the World Trade Center, mark- ing the event with not one, not two but three separate receptions — one for clients and other guests, the second for alumni and a third for families of DH&S people. On the other hand, seen in per- spective against the time and planning required for moving a practice office of almost eight hundred people without seriously interrupting the normal flow of professional activity, and the awesome size of the World Trade Center itself, the three receptions held last fall were cer- tainly in scale. Pat Waide, partner in charge in New York, began talks with the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, owner of the World Trade Center, almost two years earlier Before moving to the WTC the office had been located at Two Broadway, near Battery Park at the southern tip of Manhattan Island. -

Basketball Has Always Been a Tall Man's Game…

Basketball has always been a tall man’s game…. except when it isn’t. A realization that their mostly immigrant clientele included a lot of short people, coupled with a desire to involve as many youngsters as possible in healthy afterschool recreation, prompted founding administrators to adopt a two-tiered system of basketball: heavyweight and lightweight when the Catholic League was formed in 1912. The league would feature separate levels of varsity competition for players of varying sizes. Weight was, originally, the determining factor. Later it was changed to height: a 5foot 8 inches limit, then a still less-than-towering 5 foot 9 inches. The names never changed; the bigger team was known as the “heavies” and the smaller one as the “lights” for the 60+ years the system existed. Lightweight basketball went away when the Catholic League joined the IHSA for the 1973- 74 school year. Mendel, which also has gone away, holds the distinction of being the last lightweight league champion, crowned in 1973. Some still mourn the passing of short-guy basketball. “It gave guys like me a chance to play,” said Dick Devine, the former Cook County State’s Attorney who jumped center at 5foot8 for Loyola Academy’s Catholic League North lightweight champions in 1962. “There was no way I was going to play on the heavies.” Whatever was in the water that restricted growth might also have fueled the political ambitions of certain players. In addition to Devine, former Mayor Richard M. Daley played lightweight basketball at De La Salle in 1959-60. -

Wake Forest Magazine December 2001

2000-2001 Honor Roll of Donors Wake For e st M A G A Z I N E Volume 49, Number 2 December 2001 Wake For e st M A G A Z I N E and Honor Roll of Donors Features 16 After Disaster by Cherin C. Poovey An American tragedy bonds the University community in patriotism, compassion, unity, and hope. 23 Religion of Peace? by Charles A. Kimball Understanding Islam means grasping its complexities, which are rooted in rancor. 28 Opportunity Knocks by Liz Switzer The Richter Scholarships open doors for five students to study abroad— and open their eyes as well. Page 16 Essay 34 Great Expectations Page 28 by Leah P. McCoy Reflective students in the Class of 2001 say Wake Forest met most of theirs. Departments Campus Chronicle 2 52 Honor Roll of Donors 14 Sports 37 Class Notes Page 34 Volume 49, Number 2 December 2001 2 Campus Chronicle New school ‘a natural partnership’ Engineering a President Thomas K. Hearn Dean, senior vice president for Jr. said the new school will aid health affairs of Wake Forest. r esource in the transformation of “Currently, all of the top NIH- Winston-Salem’s economy. funded institutions have an AKE FOREST and “The school will strengthen engineering school or biomed- WVirginia Tech (Virginia Wake Forest’s intellectual ical engineering department. Polytechnic Institute and resources, thereby strengthening This new school will address State University) have the capabilities of the Piedmont the goals of both institutions.” announced plans to establish Triad Research Park.” If the planning proceeds as a joint School of Biomedical “This is a natural partner- hoped, the universities will Engineering and Sciences. -

2019 Fordham Baseball

Fordham Game Notes ~ NCAA Regional 2019 Fordham Baseball Associate Sports Information Director (Baseball Contact): Scott Kwiatkowski Email: [email protected] | Office: 718-817-4219 | Cell: 914-262-5440 | Fax: 718-817-4244 2019 NCAA Regional MEDIA INFORMATION Morgantown, W. Va. - Monongalia County Ballpark Webcast: ESPN3/WatchESPN FORDHAM RAMS (38-22) VS. Live Stats: NCAA.com #15 WEST VIRGINIA Live Audio: WFUVsports.org MOUNTAINEERS (37-20) May 31, 2019 - 8 PM FORDHAM IN 2019 Overall Record ................................. 38-22 Atlantic 10 Record ............................. 15-9 Home Record ..................................... 21-4 Tale of the Tape (2019 Stats) Away Record ................................... 17-17 Fordham West Virginia Neutral Record .................................... 0-1 .253 Batting Average .261 298 Runs 320 SERIES HISTORY 99 Doubles 110 vs. West Virginia ................................. 1-3 13 Triples 9 25 Home Runs 47 250 RBI 292 FORDHAM AT NCAA 177-225 SB-Att 93-133 Championship Appearances ................ 8 3.08 ERA 3.63 (1952, 1953, 1987, 1988, 1990, 1993, 1998, 2019) 17 Saves 14 Record at Championship ................. 4-12 592 Strikeouts 562 Last Game at NCAA .......................L, 5-1 .220 Opponent Batting Average .218 vs. The Citadel (5/22/98) PROBABLE STARTERS Fordham’s Probable Starters in the Field... RHP John Stankiewicz (8-3, 1.21) vs. LHP Nick Snyder (8-1, 2.71) Follow the Rams... @FordhamBaseball (Twitter) #18 Baker #32 Godrick #7 Melendez @FordhamBaseball (Instagram) FordhamAthletics (Facebook) #3 MacKenzie #10 Vazquez FordhamAthletics (Instagram) FORDHAM MED. GREY FORDHAM MAROON FORDHAM BLACK PANTONE BLACK 30% PANTONE 209 C PANTONE BLACK @FordhamRams (Twitter) #12 Tarabek #28 Labella #11 Bardwell Did You - Fordham is the Winningest Baseball Program in NCAA History with over 4,450 Wins - Former Fordham Head Coach Jack Coffey was a part of 1,000 wins as a player and Know? coach, while being the only major league player to play with Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth. -

2019 California League Record Book & Media Guide

2019_CALeague Record Book Cover copy.pdf 2/26/2019 3:21:27 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 2019 California League Record Book & Media Guide California League Championship Rings Displayed on the Front Cover: Inland Empire 66ers (2013) Lake Elsinore Storm (2011) Lancaster JetHawks (2014) Modesto Nuts (2017) Rancho Cucamonga Quakes (2015) San Jose Giants (2010) Stockton Ports (2008) Visalia Oaks (1978) Record Book compiled and edited by Chris R. Lampe Cover by Leyton Lampe Printed by Pacific Printing (San Jose, California) This book has been produced to share the history and the tradition of the California League with the media, the fans and the teams. While the records belong to the California League and its teams, it is the hope of the league that the publication of this book will enrich the love of the game of baseball for fans everywhere. Bibliography: Baarns, Donny. Goshen & Giddings - 65 Years of Visalia Professional Baseball. Top of the Third Inc., 2011. Baseball America Almanac, 1984-2019, Durham: Baseball America, Inc. Baseball America Directory, 1983-2018, Durham: Baseball America, Inc. Official Baseball Guide, 1942-2006, St. Louis: The Sporting News. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 2007. Baseball America, Inc. Total Baseball, 7th Edition, 2001. Total Sports. Weiss, William J. ed., California League Record Book, 2004. Who's Who in Baseball, 1942-2016, Who's Who in Baseball Magazine, Co., Inc. For More Information on the California League: For information on California League records and questions please contact Chris R. Lampe, California League Historian. He can be reached by E-Mail at: [email protected] or on his cell phone at (408) 568-4441 For additional information on the California League, contact Michael Rinehart, Jr.