Photographs of Falling Bodies and the Ethics of Vulnerability in Jonathan Safran Foer’S Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close Chris Vanderwees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flying Man and Falling Man: Remembering and Forgetting 9/11 Graley Herren Xavier University - Cincinnati

Xavier University Exhibit Faculty Scholarship English 2014 Flying Man and Falling Man: Remembering and Forgetting 9/11 Graley Herren Xavier University - Cincinnati Follow this and additional works at: http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/english_faculty Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Herren, Graley, "Flying Man and Falling Man: Remembering and Forgetting 9/11" (2014). Faculty Scholarship. Paper 3. http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/english_faculty/3 This Book Chapter/Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the English at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 9 Flying Man and Falling Man Remembering and Forgetting 9 /11 Graley Herren More than a decade after the September 11 attacks, Ame~cans continue struggling to assimilate what happened on that day. This chapter consi ders how key icons, performances, and spectacles have intersected with narrative reconstructions to mediate collective memories of 9/11, within New York City, throughout the United States, and around the globe. In Cloning Tenvr: The War of Images, 9/11 to the Present, W. J. T. Mitchell starts from this sound historiographical premise: "Every history is really two histories. There is the history of what actually happened, and there is the history of the perception of what happened. The first kind of history focuses on the facts and figures; the second concentrates on the images and words that define the framework within which those facts and figures make sense" (xi). What follows is an examination of that second kind of history: the perceptual frameworks for making sense of 9/11, frameworks forged by New Yorkers at Ground Zero, Americans removed from the attacks, and cultural creators and commentators from abroad. -

Don Delillo and 9/11: a Question of Response

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 5-2010 Don DeLillo and 9/11: A Question of Response Michael Jamieson University of Nebraska at Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Jamieson, Michael, "Don DeLillo and 9/11: A Question of Response" (2010). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 28. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/28 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. DON DELILLO AND 9/11: A QUESTION OF RESPONSE by Michael A. Jamieson A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: English Under the Supervision of Professor Marco Abel Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2010 DON DELILLO AND 9/11: A QUESTION OF RESPONSE Michael Jamieson, M.A. University of Nebraska, 2010 Advisor: Marco Abel In the wake of the attacks of September 11th, many artists struggled with how to respond to the horror. In literature, Don DeLillo was one of the first authors to pose a significant, fictionalized investigation of the day. In this thesis, Michael Jamieson argues that DeLillo’s post-9/11 work constitutes a new form of response to the tragedy. -

TM 3.1 Inventory of Affected Businesses

N E W Y O R K M E T R O P O L I T A N T R A N S P O R T A T I O N C O U N C I L D E M O G R A P H I C A N D S O C I O E C O N O M I C F O R E C A S T I N G POST SEPTEMBER 11TH IMPACTS T E C H N I C A L M E M O R A N D U M NO. 3.1 INVENTORY OF AFFECTED BUSINESSES: THEIR CHARACTERISTICS AND AFTERMATH This study is funded by a matching grant from the Federal Highway Administration, under NYSDOT PIN PT 1949911. PRIME CONSULTANT: URBANOMICS 115 5TH AVENUE 3RD FLOOR NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10003 The preparation of this report was financed in part through funds from the Federal Highway Administration and FTA. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The contents of this report reflect the views of the author who is responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do no necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the Federal Highway Administration, FTA, nor of the New York Metropolitan Transportation Council. This report does not constitute a standard, specification or regulation. T E C H N I C A L M E M O R A N D U M NO. -

11 July 2006 Mumbai Train Bombings

11 July 2006 Mumbai train bombings July 2006 Mumbai train bombings One of the bomb-damaged coaches Location Mumbai, India Target(s) Mumbai Suburban Railway Date 11 July 2006 18:24 – 18:35 (UTC+5.5) Attack Type Bombings Fatalities 209 Injuries 714 Perpetrator(s) Terrorist outfits—Student Islamic Movement of India (SIMI), Lashkar-e-Toiba (LeT; These are alleged perperators as legal proceedings have not yet taken place.) Map showing the 'Western line' and blast locations. The 11 July 2006 Mumbai train bombings were a series of seven bomb blasts that took place over a period of 11 minutes on the Suburban Railway in Mumbai (formerly known as Bombay), capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and India's financial capital. 209 people lost their lives and over 700 were injured in the attacks. Details The bombs were placed on trains plying on the western line of the suburban ("local") train network, which forms the backbone of the city's transport network. The first blast reportedly took place at 18:24 IST (12:54 UTC), and the explosions continued for approximately eleven minutes, until 18:35, during the after-work rush hour. All the bombs had been placed in the first-class "general" compartments (some compartments are reserved for women, called "ladies" compartments) of several trains running from Churchgate, the city-centre end of the western railway line, to the western suburbs of the city. They exploded at or in the near vicinity of the suburban railway stations of Matunga Road, Mahim, Bandra, Khar Road, Jogeshwari, Bhayandar and Borivali. -

3.1 Anti-Colonial Terrorism: the Algerian Struggle

1 EMMANOUIL ARETOULAKIS National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece Terrorism and Literariness: The terrorist event in the 20th and 21st centuries 2 Terrorism and Literariness: The terrorist event in the 20th and 21st centuries Author Emmanouil Aretoulakis NATIONAL AND KAPODISTRIAN UNIVERSITY OF ATHENS, GREECE Critical Reader William Schultz Editor Anastasia Tsiadimou ISBN: 978-960-603-462-6 Copyright © ΣΔΑΒ, 2015 Το παρόν έργο αδειοδοηείηαι σπό ηοσς όροσς ηης άδειας Creative Commons. Αναθορά Γημιοσργού - Μη Δμπορική Χρήζη - Παρόμοια Γιανομή 3.0. Για να δείηε ένα ανηίγραθο ηης άδειας ασηής επιζκεθηείηε ηον ιζηόηοπο https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/gr/ HELLENIC ACADEMIC LIBRARIES Δθνικό Μεηζόβιο Πολσηετνείο Ζρώων Πολσηετνείοσ 9, 15780 Εωγράθοσ www.kallipos.gr 3 Front cover picture Baricades set up during the Algerian War of Independence. January 1960. Street of Algier. Photo by Michel Marcheux, CC-BY-SA-2.5,wikipedia http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image 4 Table of Contents Abbreviation List ........................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 8 The end of History, the Clash of Civilizations and the question of the Real: Historico-Political Peregrinations ............................................................................ 12 Revolutionary Art, Theory, and Literature as Violence ........................................... 18 Notes........................................................................................................................ -

Frise Historique

Construction on the north tower The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey began began. obtaining property at the World Trade Center site. 01/08/1968 01/03/1965 Demolition at the site began with the clearance of thirteen square blocks of low rise buildings for construction of the Minoru Yamasaki, The The Port Authority chose the current site for the World Trade World Trade Center. architect of the World Center. 01/01/1966 Trade Center. 20/09/1962 1960 Minoru Yamasaki was selected to design the project. He was a second generation Groundbreaking for the construction began on Japanese-American who studied architecture at the August 5, 1966. Site preparations were vast and University of Washington and New York University. included an elaborate method of foundation work Construction of He considered hundreds of different building for which a "bathtub" had to be built 65 feet configurations before deciding on the twin towers below grade. The bathtub was made of a bentonite the south tower design. The Port Authority unveiled the $525 million (absorbent clay) slurry wall intended to keep out World Trade Center plan to the public. It was a groundwater and the Hudson River. began. composite of six buildings comprised of 10 million Yamasaki's design for the World Trade square feet of office space. At its core were the Twin Center was unveiled to the public. 01/01/1969 Towers, which at 110 stories (1,368 and 1,362 feet) The design consisted of a square plan each would be the world's tallest skyscrapers. approximately 207 feet in dimension on each side. -

The Falling Man by Tom Junod

The Falling Man By Tom Junod Do you remember this photograph? In the United States, people have taken pains to banish it from the record of September 11, 2001. The story behind it, though, and the search for the man pictured in it, are our most intimate connection to the horror of that day. http://www.esquire.com/features/ESQ0903-SEP_FALLINGMAN Originally appeared in the September 2003 issue of ESQUIRE magazine. In the picture, he departs from this earth like an arrow. Although he has not chosen his fate, he appears to have, in his last instants of life, embraced it. If he were not falling, he might very well be flying. He appears relaxed, hurtling through the air. He appears comfortable in the grip of unimaginable motion. He does not appear intimidated by gravity's divine suction or by what awaits him. His arms are by his side, only slightly outriggered. His left leg is bent at the knee, almost casually. His white shirt, or jacket, or frock, is billowing free of his black pants. His black high-tops are still on his feet. In all the other pictures, the people who did what he did -- who jumped -- appear to be struggling against horrific discrepancies of scale. They are made puny by the backdrop of the towers, which loom like colossi, and then by the event itself. Some of them are shirtless; their shoes fly off as they flail and fall; they look confused, as though trying to swim down the side of a mountain. The man in the picture, by contrast, is perfectly vertical, and so is in accord with the lines of the buildings behind him. -

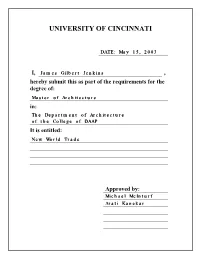

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI DATE: May 15, 2003 I, James Gilbert Jenkins , hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Architecture in: The Department of Architecture of the College of DAAP It is entitled: New World Trade Approved by: Michael McInturf Arati Kanekar NEW WORLD TRADE A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE In the Department of Architecture Of the College of Design, Art, Architecture, and Planing 2003 by James G. Jenkins B.S., University of Cincinnati, 2001 Committee Chair : Michael Mcinturf Abstract In these Modern Times, “facts” and “proofs” seem necessary for achieving any credibility in a field where there is a client. To arrive at a “truth,” many architects quickly turn to a dictionary for the final “truth” of a word, such as “privacy” or to a road map to find the “truth” in site conditions, or to a census count for the “truth” of people migration. It is, of coarse, part of the Modern Crisis that many feel the need to go with the way of technology, for fear that Architecture might otherwise fall by the wayside because of its perceived irrelevancy or frivolousness. Following this action, with time, could very well reduce Architecture to a form of methodology and inevitably end with the replacement or removal of the profession from its importance- as creators of a “Truth.” The following thesis is a serious reclamation. The body of work moves to take back for Architecture its power, and specifically it holds up and praises the most important thing we have, but in modern times have been giving away: Life. -

SEPTEMBER 11Th: ART LOSS, DAMAGE, and REPERCUSSIONS Proceedings of an IFAR Symposium

International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR) www.ifar.org This article may not be published or printed elsewhere without the express permission of IFAR. SEPTEMBER 11th: ART LOSS, DAMAGE, AND REPERCUSSIONS Proceedings of an IFAR Symposium SPEAKERS • Saul S. Wenegrat: Art Consultant; Former • Dietrich von Frank: President and CEO, AXA Art Director, Art Program, Port Authority of NY and NJ Insurance Corporation • Elyn Zimmerman: Sculptor (World Trade Center • Gregory J. Smith: Insurance Adjuster; Director, Memorial, 1993) Cunningham Lindsey International • Moukhtar Kocache: Director, Visual and Media Arts, • John Haworth: Director, George Gustav Heye Center, Lower Manhattan Cultural Council Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian • Suzanne F.W. Lemakis: Vice President and Art • Lawrence L. Reger: President, Heritage Preservation, Curator, Citigroup Heritage Emergency National Task Force IFAR SYMPOSIUM: THE ART LOST & DAMAGED ON 9/11 INTRODUCTION SHARON FLESCHER* Five months have passed since the horrific day in September that took so many lives and destroyed our sense of invulner- ability, if we were ever foolish enough to have had it in the first place. In the immediate aftermath, all we could think about was the incredible loss of life, but as we now know, there was also extensive loss of art—an estimated $100 mil- lion loss in public art and an untold amount in private and corporate collections. In addition, the tragedy impacted the art world in myriad other ways, from the precipitous drop in museum attendance, to the dislocation of downtown artists’ Left to right: Sharon Flescher, Saul S. Wenegrat, Elyn studios and arts organizations, to the decrease in philan- Zimmerman, Moukhtar Kocache, and Suzanne F. -

From “The Falling Man” to Girly Man: American Poetry After 9/ 11 and the Logic of Mourning

【연구논문】 From “The Falling Man” to Girly Man: American Poetry after 9/ 11 and the Logic of Mourning Eun-Gwi Chung (Inha University) 1. “The Falling Man”: Impossibility of 9/11 Representation In October 2001, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, an American poet, painter, and liberal activist, predicted that “poetry from now on would be divided into two categories: B.S. and A.S., Before September 11 and After September 11.”1) His reckoning, reminding me of Adorno’s famous remarks about the impossibility of poetry after Auschwitz,2) goes with the general response to 9/11, which locates 9/11 as a 1) Jeffrey Gray, “Precocious Testimony: Poetry and the Uncommemorable,” in Literature after 9/11, ed. Ann Keniston and Jenne Follansbee Quinn (New York: Routledge, 2008). 2) Lines such as Adorno’s “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric” and “all post-Auschwitz culture, including its critique, is garbage” have been quoted as examples of the limit of representation. Theodor W. Adorno, “Cultural Criticism and Society,” in Can One Live after Auschwitz? A Philosophical Reader, ed. Rolf Tiedemann (Stanford: Stanford UP, 2003), 162; idem, Negative Dialectics, trans. E. B. Ashton (New York: Continuum, 1973), 367. 64 Eun-Gwi Chung watershed moment for American society, culture, and literature. In fact, in so many kinds of literary representations of 9/11, a lingering emotion of loss or a mood of mourning has coexisted with, or ended in, the evocation of the impossibility of representation. For example, Wislawa Szymborska’s 2005 poem, “Photograph from September 11,” begins by describing the stark reality of that day in a controlled, ‘so called, poetic’ mode and ends with the evocation of the impossibility of poetic representation: “They jumped from the burning floors- / one, two, a few more, / higher, lower. -

Falling Men in 9/11 American Fiction

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 2015 FALLING MEN IN 9/11 AMERICAN FICTION Justin D. Shaw Wilfrid Laurier University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Shaw, Justin D., "FALLING MEN IN 9/11 AMERICAN FICTION" (2015). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1713. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1713 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FALLING MEN IN 9/11 AMERICAN FICTION by Justin Shaw DISSERTATION Submitted to the Department/Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Doctor of Philosophy in English and Film Wilfrid Laurier University © Justin Duane Shaw 2014 Abstract “Falling Men” in 9/11 American Fiction Gender critics such as Judith Butler and Michael Kimmel argue that post-9/11 American culture has embraced a traditional gender binary that positions men as the dominant protectors of women, children, and the nation as a whole, exemplified by the widespread veneration of heroic firefighters, soldiers, and the civilians of flight 93 in the media (Kimmel 249). This regression reinforces hegemonic masculinity in American culture, which R.W. Connell defines as “the pattern of practice (i.e., things done, not just a set of role expectations or an identity) that allow[s] men’s dominance over women to continue” (Connell and Messerschmidt 832). -

DH&S New York Celebrates Move to World Trade Center

University of Mississippi eGrove Haskins and Sells Publications Deloitte Collection 1981 DH&S New York celebrates move to World Trade Center Anonymous Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/dl_hs Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation DH&S Reports, Vol. 18, (1981 no. 1), p. 21-28 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Deloitte Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Haskins and Sells Publications by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. t was with panache and a distinctive Big Apple flair that the New York Ioffice formally celebrated its relo- cation to the World Trade Center, mark- ing the event with not one, not two but three separate receptions — one for clients and other guests, the second for alumni and a third for families of DH&S people. On the other hand, seen in per- spective against the time and planning required for moving a practice office of almost eight hundred people without seriously interrupting the normal flow of professional activity, and the awesome size of the World Trade Center itself, the three receptions held last fall were cer- tainly in scale. Pat Waide, partner in charge in New York, began talks with the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, owner of the World Trade Center, almost two years earlier Before moving to the WTC the office had been located at Two Broadway, near Battery Park at the southern tip of Manhattan Island.