Marshall Mcluhan, Rhetoric, and the Prehistory of Media Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

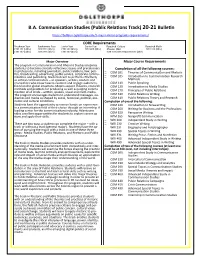

B.A. Communication Studies (Public Relations Track) 20-21 Bulletin

B.A. Communication Studies (Public Relations Track) 20-21 Bulletin https://bulletin.oglethorpe.edu/9-major-minor-programs-requirements/ CORE Requirements Freshman Year Sophomore Year Junior Year Senior Year Required Culture Required Math COR 101 ( 4hrs) COR 201 ( 4hrs) COR 301 (4hrs) COR 400 (4hrs) Choose One: COR 314 (4hrs) COR 102 ( 4hrs) COR 202 ( 4hrs) COR 302 (4hrs) COR 103/COR 104/COR 105 (4hrs) Major Overview Major Course Requirements The program in Communication and Rhetoric Studies prepares students to become critically reflective citizens and practitioners Completion of all the following courses: in professions, including journalism, public relations, law, poli- COM 101 Theories of Communication and Rhetoric tics, broadcasting, advertising, public service, corporate commu- nications and publishing. Students learn to perform effectively COM 105 Introduction to Communication Research as ethical communicators – as speakers, writers, readers and Methods researchers who know how to examine and engage audiences, COM 110 Public Speaking from local to global situations. Majors acquire theories, research COM 120 Introduction to Media Studies methods and practices for producing as well as judging commu- COM 270 Principles of Public Relations nication of all kinds – written, spoken, visual and multi-media. The program encourages students to understand messages, au- COM 310 Public Relations Writing diences and media as shaped by social, historical, political, eco- COM 410 Public Relations Theory and Research nomic and cultural conditions. Completion of one of the following: Students have the opportunity to receive hands-on experience COM 240 Introduction to Newswriting in a communication field of their choice through an internship. A COM 260 Writing for Business and the Professions leading center for the communications industry, Atlanta pro- vides excellent opportunities for students to explore career op- COM 320 Persuasive Writing tions and apply their skills. -

Features of Media Multitasking Experiences

WP2 MEDIA MULTITASKING D2.3.3.6 FEATURES OF MEDIA MULTITASKING EXPERIENCES Media Multitasking D2.3.3.6 Features of media multitasking experience s Authors: Maria Viitanen, Stina Westman, Teemu Kinnunen, Pirkko Oittinen Confidentiality: Consortium Date and status: August 31st , 2012, version 0.1 This work was supported by TEKES as part of the next Media programme of TIVIT (Finnish Strategic Centre for Science, Technology and Innovation in the field of ICT) Next Media - a Tivit Programme Phase 3 (1.1.–31.12.2012) Version history: Version Date State Author(s) OR Remarks (draft/ /update/ final) Editor/Contributors 0.1 31 st August MV, SW, TK, PO Review version {Participants = all research organisations and companies involved in the making of the deliverable} Participants Name Organisation Maria Viitanen Aalto University Researchers Stina Westman Department of Media Teemu Kinnunen Technology Pirkko Oittinen next Media www.nextmedia.fi www.tivit.fi WP2 MEDIA MULTITASKING D2.3.3.6 FEATURES OF MEDIA MULTITASKING EXPERIENCES 1 (40) Next Media - a Tivit Programme Phase 3 (1.1.–31.12.2012) Executive Summary Media multitasking is gaining attention as a phenomenon affecting media consumption especially among younger generations. From both social and technical viewpoints it is an important shift in media use, affecting and providing opportunities for content providers, system designers and advertisers alike. Media multitasking may be divided into media multitasking which refers to using several media together and multitasking with media, which consists of combining non- media activities with media use. In this deliverable we review research on multitasking from various disciplines: cognitive psychology, education, human-computer interaction, information science, marketing, media and communication studies, and organizational studies. -

Media Studies and Production Diploam Program Guide

Media Studies and Production Diploma - 31 credits Program Area: Media Studies (Fall 2019) ***REMEMBER TO REGISTER EARLY*** Program Description Required Courses This program is designed to Course Course Title Credits Term prepare the graduate for a wide MCOM 1400* Intro to Mass 3 Communication variety of positions in media MCOM 1420* Digital Video 3 production. Graduates are trained Production for jobs ranging from highly visible MCOM 1422* Audio for the Media 3 on-the-air assignments to positions ENGL 1106* College Composition I 3 on production or news teams. MCOM 1424 Digital Video Editing 3 Graduates can also gain skills MCOM 1426 Project/Production 3 needed for careers in multimedia, Management DVD authoring, film style MCOM 1428* Interactive Media 3 production, and media project & Production MCOM 1795* Portfolio Production 1 production management. Lake MCOM 1797* Media Studies 3 Superior College media studies Internship students receive valuable hands- Electives 6 on experience in LSC’s own audio (refer to Table 1) and video studios, as well as Total credits 31 through internships and *Requires a prerequisite or instructor’s consent experiences at local broadcast stations and media agencies. Program Outcomes Upon graduation, students will be able to: • Shoot and edit single camera media productions using both analog and digital equipment. • Participate in cooperative media production teams. • Voice, record, edit, and produce audio projects, promotions, and commercials using both analog and digital equipment. • Use terms and techniques common to media production and process. Pre-program Requirements Successful entry into this program requires a specific level of skill in the areas of English, mathematics, and reading. -

Journalism, Advertising, and Media Studies (JAMS)

Journalism, Advertising, and Media Studies Interested in This Major? Current Students: Visit us in Bolton Hall, Room 510B, call us at 414-229-4436 or email [email protected] Not a UWM Student yet? Call our Admissions Counselor at 414-229-7711 or email [email protected] Web: uwm.edu/journalism-advertising-media-studies JAMS at UWM Career Opportunities Media has never been more dynamic. The worlds JAMS students have a wide range of career paths open of journalism, advertising, public relations and film to them. Many seek careers in media, marketing, and are changing and growing at a rapid pace, and the communication. Others go on to pursue graduate work in the Department of Journalism, Advertising, and Media social sciences, humanities, and law. Studies (JAMS) is a great place to learn about them. Our alumni can be found in many prestigious organizations: Whether students see themselves working in news, entertainment, social media, advertising, public • Groupon • SC Johnson relations, or are fascinated by media, JAMS courses • Boston Globe • Milwaukee Brewers enable students to customize their education and • Milwaukee Journal • A.V. Club (Onion, Inc.) prepare for their chosen careers. Sentinel • WI Air National Guard Students choose courses to gain a broad • TMJ4 • United Nations understanding of the media’s place in society and • Foley & Lardner University culture, but also concentrate more closely in one of • Vice News • Boys & Girls Clubs of three areas: • WI State Legislature Greater Milwaukee Journalism. The Journalism concentration emphasizes • Bader Rutter writing, information gathering, critical thinking • New England Journal and technology skills in courses taught by media of Medicine • HSA Bank professionals. -

D4d78cb0277361f5ccf9036396b

critical terms for media studies CRITICAL TERMS FOR MEDIA STUDIES Edited by w.j.t. mitchell and mark b.n. hansen the university of chicago press Chicago and London The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2010 Printed in the United States of America 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 1 2 3 4 5 isbn- 13: 978- 0- 226- 53254- 7 (cloth) isbn- 10: 0- 226- 53254- 2 (cloth) isbn- 13: 978- 0- 226- 53255- 4 (paper) isbn- 10: 0- 226- 53255- 0 (paper) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Critical terms for media studies / edited by W. J. T. Mitchell and Mark Hansen. p. cm. Includes index. isbn-13: 978-0-226-53254-7 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-226-53254-2 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn-13: 978-0-226-53255-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-226-53255-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Literature and technology. 2. Art and technology. 3. Technology— Philosophy. 4. Digital media. 5. Mass media. 6. Image (Philosophy). I. Mitchell, W. J. T. (William John Th omas), 1942– II. Hansen, Mark B. N. (Mark Boris Nicola), 1965– pn56.t37c75 2010 302.23—dc22 2009030841 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48- 1992. Contents Introduction * W. J. T. Mitchell and Mark B. N. Hansen vii aesthetics Art * Johanna Drucker 3 Body * Bernadette Wegenstein 19 Image * W. -

MDST) Is a Distinct Track Within the Umbrella Phd in Media Research and Practice (MDRP)

Ph.D. in Media Studies I. Program Overview The PhD in Media Studies (MDST) is a distinct track within the umbrella PhD in Media Research and Practice (MDRP). Drawing largely from contemporary cultural and critical theory, the Media Studies PhD program focuses on interactions among the major components of modern communication — media institutions, their contents and messages, and their audiences or publics — as a process by which cultural meaning is generated. It examines that process on an interdisciplinary basis through social, economic, political, historical, legal/policy/regulatory and international perspectives, with a strong emphasis on issues involving new communication technology and policy. Students graduate from the program with broad knowledge of the intellectual history of media studies as an important interdisciplinary field of research—its origins; its perennial questions and controversies; its evolution in response to technological, political, economic and cultural change; the full range of methods it employs, both humanistic and social scientific – and a demonstrated capacity to design and execute original and socially significant research about media and their historical and contemporary power and importance. The program strives to produce graduates who demonstrate intellectual leadership, nationally and internationally, in the area(s) of research specialization they choose and/or pioneer, and an interest in and aptitude for generating public awareness and conversation about their scholarship. An important part of doctoral -

Communication Studies Associate in Arts for Transfer

COMMUNICATION STUDIES ASSOCIATE IN ARTS FOR TRANSFER The Communication Studies major analyzes processes of communication, commonly defined as the sharing of symbols over distances in space and time. Hence, communication studies encompasses a wide range of topics and contexts ranging from face-to-face conversation to public speeches to mass media outlets such as television broadcasting and film studies. Communication Studies, as a discipline, is also interested in how audiences interpret information from the political, cultural, economic, and social dimensions of speech and language. There are many areas of specialization offered within the Communication Studies majors including Advertising, Public Relations, Journalism, Digital Media, Organizational Communication, Intercultural Communication, Interpersonal Communication, Rhetoric, and Media Studies. Studying communication will also enhance any career, but a few specific careers include business, public relations, human resources, law [after law school], advertising arts, teaching, social services, human services, and entertainment industries are all suited for graduates with a Communication Studies degree. Finally, students who are interested in the field of Communication Studies but do not wish to complete a Baccalaureate degree in the discipline may pursue a terminal two-year course of study. Such study will prepare them to understand diverse communication messages and practice excellent communication skills in a variety of settings. For more information contact: Dr. Amy Edwards (805) -

STS Departments, Programs, and Centers Worldwide

STS Departments, Programs, and Centers Worldwide This is an admittedly incomplete list of STS departments, programs, and centers worldwide. If you know of additional academic units that belong on this list, please send the information to Trina Garrison at [email protected]. This document was last updated in April 2015. Other lists are available at http://www.stswiki.org/index.php?title=Worldwide_directory_of_STS_programs http://stsnext20.org/stsworld/sts-programs/ http://hssonline.org/resources/graduate-programs-in-history-of-science-and-related-studies/ Austria • University of Vienna, Department of Social Studies of Science http://sciencestudies.univie.ac.at/en/teaching/master-sts/ Based on high-quality research, our aim is to foster critical reflexive debate concerning the developments of science, technology and society with scientists and students from all disciplines, but also with wider publics. Our research is mainly organized in third party financed projects, often based on interdisciplinary teamwork and aims at comparative analysis. Beyond this we offer our expertise and know-how in particular to practitioners working at the crossroad of science, technology and society. • Institute for Advanced Studies on Science, Technology and Society (IAS-STS) http://www.ifz.tugraz.at/ias/IAS-STS/The-Institute IAS-STS is, broadly speaking, an Institute for the enhancement of Science and Technology Studies. The IAS-STS was found to give around a dozen international researchers each year - for up to nine months - the opportunity to explore the issues published in our annually changing fellowship programme. Within the frame of this fellowship programme the IAS-STS promotes the interdisciplinary investigation of the links and interaction between science, technology and society as well as research on the development and implementation of socially and environmentally sound, sustainable technologies. -

Chapter 1. “New Media” and Marshall Mcluhan: an Introduction

Chapter 1. “New Media” and Marshall McLuhan: An Introduction “Much of what McLuhan had to say makes a good deal more sense today than it did in 1964 because he was way ahead of his time.” - Okwor Nicholaas writing in the July 21, 2005 Daily Champion (Lagos, Nigeria) “I don't necessarily agree with everything I say." – Marshall McLuhan 1.1 Objectives of this Book The objective of this book is to develop an understanding of “new media” and their impact using the ideas and methodology of Marshall McLuhan, with whom I had the privilege of a six year collaboration. We want to understand how the “new media” are changing our world. We will also examine how the “new media” are impacting the traditional or older media that McLuhan (1964) studied in Understanding Media: Extensions of Man hereafter simply referred to simply as UM. In pursuing these objectives we hope to extend and update McLuhan’s life long analysis of media. One final objective is to give the reader a better understanding of McLuhan’s revolutionary body of work, which is often misunderstood and criticized because of a lack of understanding of exactly what McLuhan was trying to achieve through his work. Philip Marchand in an April 30, 2006 Toronto Star article unaware of my project nevertheless described my motivation for writing this book and the importance of McLuhan to understanding “new media”: Slowly but surely, McLuhan's star is rising. He's still not very respectable academically, but those wanting to understand the new technologies, from the iPod to the Internet, are going back to read what the master had to say about television and computers and the process of technological change in general. -

Sauterdivineansamplepages (Pdf)

The Decline of Space: Euclid between the Ancient and Medieval Worlds Michael J. Sauter División de Historia Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas, A.C. Carretera México-Toluca 3655 Colonia Lomas de Santa Fe 01210 México, Distrito Federal Tel: (+52) 55-5727-9800 x2150 Table of Contents List of Illustrations ............................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgments .............................................................................................................. v Preface ............................................................................................................................... vi Introduction: The divine and the decline of space .............................................................. 1 Chapter 1: Divinus absconditus .......................................................................................... 2 Chapter 2: The problem of continuity ............................................................................... 19 Chapter 3: The space of hierarchy .................................................................................... 21 Chapter 4: Euclid in Purgatory ......................................................................................... 40 Chapter 5: The ladder of reason ........................................................................................ 63 Chapter 6: The harvest of homogeneity ............................................................................ 98 Conclusion: The -

Critical Discourse Analysis: Mass Media

Critical Discourse Analysis: Mass Media Deti Anitasari Department of English Education, Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Universitas Lancang Kuning [email protected] ABSTRACT: In this paper, the researcher aims are to review some key problems of approaches to research on mass media text from point of view discourse analytical and to present an argument, as well as a Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) structures for analysis of mass media discourse. The researcher regards a number of areas of critical research interest in mass media discourse locally and elsewhere. An instance of actual CDA researches on mass media discourse is reviewed in terms of topics of obviously popular interest among society, before listing methodological, as well as the topical plan by a main support in the field for further work. This paper concludes that CDA’s multidisciplinary approach helps to understand and aware of the hidden socio-political issues and agenda in all kinds of areas of language as a social practice to empower the individual and social groups. Keywords: Critical Discourse Analysis, Critical Discourse studies, Mass Media Discourse, Media text Analysis INTRODUCTION human talks to one another via verbal and non-verbal means, but which Discourse has been explained as concerns messages that are essentially structures and practices that reflect transmitted through a medium (channel) human thought and social realities to reach a large number of people through particular collections of words (Wimmer & Dominick, 2012, Devito, and that simultaneously construct 2011). From the beginning, for a clear meaning in the world (Fairclough, 2003). point of view on the problems relating to Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) mass media effects, it is helpful to proposes a research methodology for clarify what constitutes mass media in deconstructing discourses and fixed current communication studies, i.e. -

Sacramentum Caritatis As the Foundation of Augustine's Spirituality

SACRAMENTUM CARITATIS AS THE FOUNDATION OF AUGUSTINE'S SPIRITUALITY ROBERT 00DARO As a working definition of "Christian spirituality" let me propose one given by the Dutch Augustinian scholar, Father Tarcisius van Bavel. Speaking to a group of Augustinian friars in I 986, he admitted that the notion of Christian spirituality was broad, and that one rarely found it described in religious literature. It might be con· ceived, he said, as a "window on the GospeL an outlook on the Gospel." All authen· tic Christian spiritualities are responses to the Gospel, but "no two persons can read the Gospel in an entirely identical way." Each one "inevitably listens in a personal way, ... lays stress on different things and has a number of favorite texts."' Thus, a window screening in and out of view different concrete features of the Gospel, enables a given spirituality to accent particular evangelical values over oth· ers. At the same time, because each Christian spirituality is a "window on the Gospel," when it is properly embraced it leads its adherents into the whole truth of the Gospel. Father van BaveJ thus distinguishes Augustinian spirituality from its Benedictine, Cistercian, Franciscan, and Ignatian alternatives by stipulating the dis· tinctive role of love of neighbor and community life which Augustinian spirituality emphasizes. By way of illustrating his point, Fr. van Bavel stated, in an off·the-cuff remark, that in the Benedictine tradition, the monastery church was the center of life; in an Augustinian friary, the center of life is found in the common room. Prayer, though important for Augustine, is thus not the center of his spirituality.