I Slummary This Report, Which Attemptss to Evaluate the Case for Separate Senior High Schools in N.S.W. , Ccommences with Backgr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 GONSKI FUNDING NSW Public Schools by Federal Electorate

2017 GONSKI FUNDING 1 of 2 NSW public schools by federal electorate Federal electorate: Cook Federal MP party affiliation: Liberal Total increase in recurrent funding (2014-2017): $4,455,967 State MP 2017 funding Total funding State School party change from change electorate affiliation 2016 ($) 2014 - 2017 ($) BALD FACE PUBLIC SCHOOL Oatley Liberal 32,963 55,153 BLAKEHURST PUBLIC SCHOOL Kogarah Labor 28,352 32,892 BOTANY BAY ENVIRONMENTAL Cronulla Liberal 5,981 8,472 EDUCATION CENTRE BURRANEER BAY PUBLIC SCHOOL Cronulla Liberal 93,531 120,522 CARINGBAH HIGH SCHOOL Cronulla Liberal 81,784 173,826 CARINGBAH NORTH PUBLIC SCHOOL Cronulla Liberal 104,698 141,286 CARINGBAH PUBLIC SCHOOL Cronulla Liberal 23,042 62,876 CRONULLA HIGH SCHOOL Cronulla Liberal 78,941 264,962 CRONULLA PUBLIC SCHOOL Cronulla Liberal 29,975 67,362 CRONULLA SOUTH PUBLIC SCHOOL Cronulla Liberal 32,911 58,670 ENDEAVOUR SPORTS HIGH SCHOOL Miranda Liberal 187,134 360,245 GYMEA BAY PUBLIC SCHOOL Cronulla Liberal 113,094 216,855 GYMEA NORTH PUBLIC SCHOOL Miranda Liberal 60,250 104,713 GYMEA TECHNOLOGY HIGH SCHOOL Miranda Liberal 72,208 319,347 JAMES COOK BOYS TECHNOLOGY HIGH Rockdale Labor 50,045 92,155 KURNELL PUBLIC SCHOOL Cronulla Liberal 50,768 116,941 LAGUNA STREET PUBLIC SCHOOL Cronulla Liberal 59,259 71,337 LILLI PILLI PUBLIC SCHOOL Cronulla Liberal 44,775 89,075 MIRANDA NORTH PUBLIC SCHOOL Miranda Liberal 56,027 90,770 MIRANDA PUBLIC SCHOOL Miranda Liberal 42,677 109,720 MOOREFIELD GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL Rockdale Labor 81,224 198,210 PORT HACKING HIGH SCHOOL Miranda Liberal 156,481 331,429 RAMSGATE PUBLIC SCHOOL Rockdale Labor 96,213 223,918 SANS SOUCI PUBLIC SCHOOL Rockdale Labor 85,585 145,912 ST. -

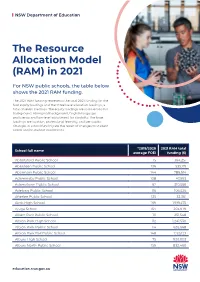

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 347,551 Alma Public -

Carnival Program

New South Wales Combined High Schools Sports Association Boys’ Football Championships 4 ‐ 6 May 2021 Kirrawee Hosted by Sydney East Schools Sports Association in conjunction with the NSW Department of Education School Sport Unit NSWCHSSA Executive President Simon Warren BWSC – Umina Campus Vice Presidents Brett Austine Belmont HS Margot Brissenden Woolgoolga HS Jacqui Charlton Swansea HS Mark Skein Canobolas Technology HS Treasurer Gavin Holburn Kingswood HS Executive Officer Jacky Patrick School Sport Unit Football Convener Ron Pratt Wyndham College Sydney East SSA Executive President Dave Haggart Kogarah HS Senior Vice President Dave Stewart The Jannali HS Vice President Craig Holmes Heathcote High School Treasurer Peter George SSC Blackwattle Bay Campus Executive Officer Bruce Riley School Sport Unit Sydney East Convener Peter Slater Blakehurst High School Championship Management Vicki Smith School Sport Unit Garry Moore The Jannali High School Welcome from the NSWCHSSA President Sport continues to play a significant role in building the Australian character and that of the youth of today, not only in Football but also in all the sports that the NSWCHSSA conducts. The Association endeavours to provide a wide range of sporting activities and opportunities for all students in our public high schools. For over 130 years, competition has been provided at a variety of levels by willing and dedicated teachers to help the pupils in our schools reach their potential at their selected sport. At this stage, I must thank all those principals, coaches, managers, parents, officials and participants who have strived so hard to make our championships successful. Much of this time is done on a voluntary basis and it is greatly appreciated. -

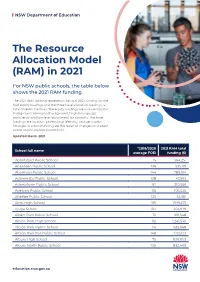

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. Updated March 2021 *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 -

Volunteer Availability

Volunteer Availability Name: SESSION DATE/TIME VISITOR DETAILS AVAILABILITY (please tick) Wednesday, 4 June 2014 11:00 AM - 1:00 PM David Martin Macquarie College 17 students (17 Yr 12 PDHPE ) Thursday, 5 June 2014 9:00 AM - 11:00 AM Lorna Fitzgibbons St Andrews Cathedral School 30 students (30 Yr 12 Bio ) 11:00 AM - 1:00 PM Steven Millard Tyndale Christian School 23 students (23 Yr 12 Bio ) 11:00 AM - 1:00 PM Phil Pratt Galstaun College 7 students (7 Yr 12 Bio ) 11:00 AM - 1:00 PM Rina Naiker East Hills Boys Technology High School 41 students (41 Yr 12 Bio ) 11:00 AM - 1:00 PM Rina Naiker East Hills Boys Technology High School 37 students (37 Yr 12 Bio ) 1:00 PM - 3:00 PM Cayte Pryor St Pauls, Booragul 30 students (30 Yr 12 Bio ) Friday, 6 June 2014 9:00 AM - 11:00 AM Marian Redmond St Mary Star of the Sea College 51 students (51 Yr 12 Bio ) 11:00 AM - 1:00 PM Narelle Wawrzyniak Model Farms High School 40 students (40 Yr 12 Bio ) 11:00 AM - 1:00 PM Zeina Hitti St Charbels College 25 students (20 Yr 12 Bio 5 Yr 12 SS 5 Yr 12 PDHPE ) 1:00 PM - 3:00 PM Terence McGrath Aquinas Catholic College 22 students (22 Yr 12 Bio ) 1:00 PM - 3:00 PM Rodrigo Cortez St Maroun's College 8 students (8 Yr 12 Bio ) Tuesday, 10 June 2014 9:00 AM - 11:00 AM Emma Coleman Leumeah Technology High School 30 students (30 Yr 12 Bio ) 11:00 AM - 1:00 PM Sue Hanrahan Oxley College 24 students (20 Yr 12 Bio 4 Yr 12 PDHPE ) Wednesday, 4 June 2014 Page 1 of 4 SESSION DATE/TIME VISITOR DETAILS AVAILABILITY (please tick) 11:00 AM - 1:00 PM Paul Boon Rosebank College 18 -

From Our Principal Celebrating Student Achievement

FROM OUR PRINCIPAL CELEBRATING STUDENT ACHIEVEMENT LIVE PERFORMANCES RETURN TO NHSPA! Congratulations to Year 12 student Olivia Term 2 is in full swing with many exciting activities planned in Fox who received the Department’s Nanga coming weeks. Our Performing Arts staff and students are busy Mai award for Outstanding Achievement in Performing, Creative and Visual Arts. Olivia preparing for the first Showcase Season since lockdown. With will be presented with her award at Year 12 over forty companies featured including choirs, percussion, wind Graduation next term. and string ensembles, jazz orchestra, junior and senior dance and Olivia Fox Year 12 drama companies, the season is bound to be an exciting and entertaining one. Showcase opened with Alumnight, an art Congratulations also to Year 8 student Aurielle Smith who was exhibition featuring the works of Newtown alumni. This is bound runner up in the playwriting to be a fascinating insight into the post school world of our section of the Young Writers’ talented former students. The exhibition will be held in our Art Competition held at the Glen St Gallery on King Street and open from 5.30-6.30pm on Showcase Theatre last holidays. nights. Aurielle Smith, Year 8 We are thrilled that our gifted music students at NHSPA will again perform with internationally acclaimed Greek vocalist Dimitris On the sporting front, Year 10 Basis as part of the 39th Greek Festival of Sydney. It is such a student Oskar Smith captained privilege for our students to play with professional musicians and the NSW under 15 State Hockey to be part of an exciting cultural celebration. -

Premier's Teacher Scholarships Alumni 2000

Premier’s Teacher Scholarships Alumni 2000 - 2016 Alumni – 2000 Premier’s American History Scholarships • Judy Adnum, Whitebridge High School • Justin Briggs, Doonside High School • Bruce Dennett, Baulkham Hills High school • Kerry John Essex, Kyogle High School • Phillip Sheldrick, Robert Townson High School Alumni – 2001 Premier’s American History Scholarships • Phillip Harvey, Shoalhaven Anglican School • Bernie Howitt, Narara Valley High School • Daryl Le Cornu, Eagle Vale High School • Brian Everingham, Birrong Girls High School • Jennifer Starink, Glenmore Park High School Alumni – 2002 Premier’s Westfield Modern History Scholarships • Julianne Beek, Narara Valley High School • Chris Blair, Woolgoolga High School • Mary Lou Gardam, Hay War Memorial High School • Jennifer Greenwell, Mosman High School • Jonathon Hart, Coffs Harbour Senior College • Paul Kiem, Trinity Catholic College • Ray Milton, Tomaree High School • Peter Ritchie, Wagga Wagga Christian College Premier’s Macquarie Bank Science Scholarships • Debbie Irwin, Strathfield Girls High School • Maleisah Eshman, Wee Waa High School • Stuart De Landre, Mt Kembla Environmental Education Centre • Kerry Ayre, St Joseph’s High School • Janine Manley, Mt St Patrick Catholic School Premier’s Special Education Scholarship • Amanda Morton, Belmore North Public School Premier’s English Literature Scholarships • Jean Archer, Maitland Grossman High School • Greg Bourne, TAFE NSW-Riverina Institute • Kathryn Edgeworth, Broken Hill High School • Lorraine Haddon, Quirindi High School -

Carnival Program

NSWCHS Executive President Simon Warren BWSC Umina Campus Vice Presidents Brett Austine Belmont HS Mark Skein Canobolas Technology HS Jacqui Charlton Swansea HS Nerida Noble Gymea HS Treasurer Gavin Holburn Kingswood HS Executive Officer Jacky Patrick School Sport Unit Football Convener Ron Pratt Wyndham College South Coast SSA Executive President Paul Creighton Dapto HS Vice President Jenny Clancy Wollongong HSPA Secretary Adam Sargent-Wilson Figtree HS Treasurer Jayne Rixon Dapto PS Principals rep Ian Morris Bomaderry HS Sport co-ordination officer Meegan Dignam School Sport Unit Girls football convener Daniel Naumovski Illawarra Sports HS Championship manager Ryan Trevor Dapto HS Welcome from the NSWCHS Football Convener It is with great pleasure that I welcome all competitors, Department of Education representatives and visitors to Wollongong for the 2018 NSW Combined High Schools Football State Carnival. The students are here this week representing their School Sports Associations, Schools and families. It is an honour to gain representative status as an athlete and we look forward to the emerging performances of those who may emulate the careers of many of the current and former Matildas, Young Matildas and W-League players who have participated previously at these championships. From this championship the NSW Combined High Schools State teams to compete in the NSW All Schools Tournament during June will be announced for fixtures against Combined Catholic Colleges and Combined Independent Schools. This event also serves as the trials for this year’s National Championships which will be held in Victoria during August. We look forward to some wonderful football with the challenge for all teams to step up to the quality football we saw from last year’s champions, Sydney West who narrowly accounted for Sydney North in the final. -

NSW Government Schools Study Abroad Brochure

New South Wales Government Schools Study Abroad 1 Doing this study abroad program was the best decision I have ever made. I participated in many sports and I joined a how-to-surf class. The places you see, the things you experience and the friends you make are unforgettable. During the holiday period I participated in a tour to Canberra, Melbourne and Queensland. It was the best year of my life and I wouldn’t change a thing about it. Monica, Germany Cronulla High School 2 Study Abroad ~ an experience of a lifetime For high school students, About Sydney and New South Wales a short-term study abroad program at a government Sydney, the capital city of New South Wales, is school in Sydney or country Australia’s largest city. It is famous for its quality New South Wales offers education, friendly people, great climate and an exciting opportunity to multicultural lifestyle. experience a uniquely Australian lifestyle while you study. New South Wales has many regional cities located near magnificent coastal beaches, national parks, There are frequent international mountain ranges and open plains. Summer and flights from Europe, North and winter recreational activities include surfing, South America to Australia. swimming, tennis, football and skiing. 3 About NSW Government Schools New South Wales (NSW) government Students may receive credit for their schools are owned and operated by Australian studies when they resume the NSW Department of Education studies in their home country. and Communities, Australia’s largest education organisation. With schools Schools are safe, friendly, multicultural across the state, you can choose the learning places. -

Participating Schools List

PARTICIPATING SCHOOLS LIST current at Saturday 11 June 2016 School / Ensemble Suburb Post Code Albion Park High School Albion Park 2527 Albury High School* Albury 2640 Albury North Public School* Albury 2640 Albury Public School* Albury 2640 Alexandria Park Community School* Alexandria 2015 Annandale North Public School* Annandale 2038 Annandale Public School* Annandale 2038 Armidale City Public School Armidale 2350 Armidale High School* Armidale 2350 Arts Alive Combined Schools Choir Killarney Beacon Hill 2100 Arts Alive Combined Schools Choir Pennant Hills Pennant Hills 2120 Ashbury Public School Ashbury 2193 Ashfield Boys High School Ashfield 2131 Asquith Girls High School Asquith 2077 Avalon Public School Avalon Beach 2107 Balgowlah Heights Public School* Balgowlah 2093 Balgowlah North Public School Balgowlah North 2093 Balranald Central School Balranald 2715 Bangor Public School Bangor 2234 Banksmeadow Public School* Botany 2019 Bathurst Public School Bathurst 2795 Baulkham Hills North Public School Baulkham Hills 2153 Beacon Hill Public School* Beacon Hill 2100 Beckom Public School Beckom 2665 Bellevue Hill Public School Bellevue Hill 2023 Bemboka Public School Bemboka 2550 Ben Venue Public School Armidale 2350 Berinba Public School Yass 2582 Bexley North Public School* Bexley 2207 Bilgola Plateau Public School Bilgola Plateau 2107 Billabong High School* Culcairn 2660 Birchgrove Public School Balmain 2041 Blairmount Public School Blairmount 2559 Blakehurst High School Blakehurst 2221 Blaxland High School Blaxland 2774 Bletchington -

2018 Minister's and Secretary's Awards for Excellence

2018 MINISTER’S AND SECRETARY’S AWARDS FOR Excellence Welcome It’s with great pleasure that I welcome you to the 2018 Minister’s and Secretary’s Awards for Excellence. These Awards showcase the best of NSW public education - our finest students, our most impressive schools and teachers, and our most committed employees and parents. The Public Education Foundation’s mission is to celebrate and support public schooling, and today’s Awards do this in spades. The Foundation is delighted to manage the Awards on behalf of The Honourable Rob We are grateful to the IPAA NSW for Stokes MP, Minister for Education & Mr Mark sponsoring these awards. Scott AO, Secretary of the NSW Department IPAA NSW is the not-for-profit professional of Education. association for people who work in or with You’ll hear today about many the public sector. Our members include extraordinary achievements and initiatives staff from all current NSW Clusters, the from across the state, from the Sydney Story NSW Public Service Commission, a range of Factory in-residence program at Canterbury Agency partners and individual members. Boys High to a new model of HUB Learning We have more than 3,000 members and at Kurri Kurri High in the Hunter Valley. deliver services directly to a community of more than 12,000 customers across the We will also show you something we’re NSW public sector. IPAA NSW facilitates high very proud of – a short clip from our new quality public administration and capability public education campaign, “Building Great development across the public sector. -

2019 Higher School Certificate- Illness/Misadventure Appeals

2019 Higher School Certificate- Illness/Misadventure Appeals Number of Number of HSC Number of Number of Number of Number of HSC Number of HSC Number of Number of HSC students student exam student exam student exam applied courses School Name Locality student exam student exam course mark exam students lodging I/M courses applied components components fully or partially courses components changes applications for applied for upheld upheld Abbotsleigh WAHROONGA 164 7 922 1266 25 31 31 25 17 Airds High School CAMPBELLTOWN 64 3 145 242 9 16 12 6 6 Al Amanah College LIVERPOOL Al Noori Muslim School GREENACRE 91 9 377 447 15 17 17 15 12 Al Sadiq College GREENACRE 41 5 212 284 9 10 10 9 4 Albion Park High School ALBION PARK 67 2 323 468 2 2 2 2 2 Albury High School ALBURY 105 6 497 680 12 13 13 12 7 Alesco Illawarra WOLLONGONG Alesco Senior College COOKS HILL 53 3 91 94 3 3 3 3 3 Alexandria Park Community School ALEXANDRIA Al-Faisal College AUBURN 114 2 565 703 6 7 7 6 5 Al-Faisal College - Campbelltown MINTO All Saints Catholic Senior College CASULA 219 10 1165 1605 27 32 31 27 14 All Saints College (St Mary's Campus) MAITLAND 204 10 1123 1475 13 15 12 10 7 All Saints Grammar BELMORE 45 2 235 326 3 3 0 0 0 Alpha Omega Senior College AUBURN 113 7 475 570 12 12 11 11 6 Alstonville High School ALSTONVILLE 97 2 461 691 4 5 5 4 2 Ambarvale High School ROSEMEADOW 74 3 290 387 9 11 11 9 6 Amity College, Prestons PRESTONS 159 5 682 883 12 14 14 12 8 Aquinas Catholic College MENAI 137 4 743 967 9 13 13 9 7 Arden Anglican School EPPING 76 9 413 588