The Rational Activist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The BCCI Affair

The BCCI Affair A Report to the Committee on Foreign Relations United States Senate by Senator John Kerry and Senator Hank Brown December 1992 102d Congress 2d Session Senate Print 102-140 This December 1992 document is the penultimate draft of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee report on the BCCI Affair. After it was released by the Committee, Sen. Hank Brown, reportedly acting at the behest of Henry Kissinger, pressed for the deletion of a few passages, particularly in Chapter 20 on "BCCI and Kissinger Associates." As a result, the final hardcopy version of the report, as published by the Government Printing Office, differs slightly from the Committee's softcopy version presented below. - Steven Aftergood Federation of American Scientists This report was originally made available on the website of the Federation of American Scientists. This version was compiled in PDF format by Public Intelligence. Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................ 4 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF INVESTIGATION ............................................................................... 21 THE ORIGIN AND EARLY YEARS OF BCCI .................................................................................................... 25 BCCI'S CRIMINALITY .................................................................................................................................. 49 BCCI'S RELATIONSHIP WITH FOREIGN GOVERNMENTS CENTRAL BANKS, AND INTERNATIONAL -

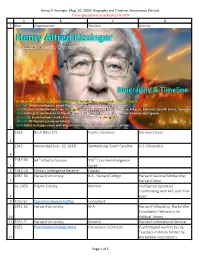

Henry A. Kissinger. (Aug

Henry A. Kissinger. (Aug. 20, 2020). Biography and Timeline. Anonymous Patriots. *.xlsx spreadsheet attached to this PDF A B C D 1 Year Organization Position Activity Henry Alfred Kissinger (b. 1923, Fuerth, Germany) Biography & Timeline Dedicated his career to the (British) Pilgrims Society "new world order" 200-year plan ca. 1948: British intelligence; joined Pilgrims Society; Pilgrims Rockefeller "advisor" 1948: Runner for the Marshall Plan stolen gold created by Pilgrims Society Stimson, Acheson, Marshall, Sarnoff, Dulles, Donovan 1971: Killed gold standard w/ 12 Nixon Pilgrims Cabinet members incl. Volcker; ran American intelligence 1971-2008: Exploited Swiss Bank of International Settlements stolen gold 2007-09: VP Pilgrims Society w/ Volcker 2008: Killed mortgage values with Pilgrims Clinton, Bush, Obama, Summers, Volcker 2 1923 Birth (May 27) Fuerth, Germany German Citizen 3 1943 Naturalized (Jun. 19, 1943) Spartanburg, South Carolina U.S. Citizenship 4 1943-46 84th Infantry Division 970th Counter-Intelligence 5 Corps 6 1946-59 Military Intelligence Reserve Captain 1947-50 Harvard University B.A., Harvard College Harvard National Scholarship; 7 Harvard Detur ca. 1950 Pilgrim Society Member Intelligence operative coordinating with MI6 and "Five 8 Eyes" 9 1950-61 Operations Research Office Consultant 1951-52 Harvard University M.A. Harvard Fellowship; Rockefeller Foundation Fellowship for 10 Political Theory 11 1951-71 Harvard University Director Harvard International Seminar 1952 Psychological Strategy Board Consultant to Director Psychological warfare (using Tavistock Institute funded by 12 Rockefeller Foundation) Page 1 of 5 Henry A. Kissinger. (Aug. 20, 2020). Biography and Timeline. Anonymous Patriots. *.xlsx spreadsheet attached to this PDF A B C D 1 Year Organization Position Activity 13 1952-54 Harvard University Ph.D. -

The Kissinger Associates Firm: a New Vehicle for British Influence

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 9, Number 36, September 21, 1982 The Kissinger Associates firm: a new vehicle for British influence by Scott Thompson When Henry A. Kissinger first emerged in control of U.S. have had a longer friendship with him than with any other executive branch policy during the late 1960s, it was the leading British political figure." A trustee of the Aspen In Trilateral Commission and that less-well-known conduit of stitute, Gyllenhammar helped Anderson arrange a computer European oligarchical policy, the Bilderberg Society, which interface among Aspen, Control Data in Sweden, IFIAS ensured Kissinger's rise to power and controlled his activi (which serves as a Swedish-basedfront for the Muslim Broth ties. A new vehicle has been prepared for Kissinger's re erhood), Soviet computers, and IIASA, the Vienna-based emergence as the leading U. S. enforcer of the programs think tank of the KGB-linked Djermen Gvishiani. Gyllen dictated to the United States by the British and European hammar is also a Chase International board member. oligarchy: Kissinger Associates, Inc. General Brent Scowcroft, who was Kissinger's Nation Kissinger Associates, a Washington, D.C.-based "con al Security Council deputy until named as his replacement as sulting firm," boasts the following board members: National Security Adviser. It was Scowcroft, Kissinger, and Lord Carrington, former British Foreign Secretary� De Haig who ran the White House inside track of Watergate, spite his resignation over the Malvinas crisis, Lord Carring supported from the outside by the Washington Pbst'$ trial ton remains one of the most influential "one world" strate by-press attacks. -

Engineering Empire

2013 Engineering Empire: An Introduction to the Intellectuals and Institutions of American Imperialism in the Age of Obama Engineering Empire: An Introduction to the Intellectuals and Institutions of American Imperialism in the Age of Obama A 2013 Hampton Institute report by Andrew Gavin Marshall Hampton Institute a proletarian think tank www.hamptonthink.org 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ENGINEERING EMPIRE ……………………………. 3 Meet the Engineers of Empire …… 4 Dynastic Influence on Foreign Policy …. 5 Intellectuals, 'Experts,' and Imperialists Par Excellence: Kissinger and Brzezinski ……. 8 From Cold War to New World Order: 'Containment' to 'Enlargement' …. 11 The Road to "Hope" and "Change" …. 16 CSIS: The 'Brain' of the Obama Administration … 18 Imperialism Without Imperialists? ….. 25 Notes …. 26 EMPIRE UNDER OBAMA, PART 1: POLITICAL LANGUAGE AND THE ‘MAFIA PRINCIPLES’ OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS ……. 30 Mafia Principles and Western 'Values' …. 33 Notes …. 39 EMPIRE UNDER OBAMA, PART 2: BARACK OBAMA’S GLOBAL TERROR CAMPAIGN … 41 Notes … 48 EMPIRE UNDER OBAMA, PART 3: AMERICA’S “SECRET WARS” IN OVER 100 COUNTRIES AROUND THE WORLD ……. 51 Notes …. 57 EMPIRE UNDER OBAMA, PART 4: COUNTERINSURGENCY, DEATH SQUADS, AND THE POPULATION AS A TARGET …… 60 Notes …. 68 2 Educating yourself about empire can be a challenging endeavor, especially since so much of the educational system is dedicated to avoiding the topic or justifying the actions of imperialism in the modern era. If one studies political science or economics, the subject might be discussed in a historical context, but rarely as a modern reality; media and government voices rarely speak on the subject, and even more rarely speak of it with direct and honest language. -

2020 Virtual Gala

2020 Virtual Gala Tuesday, November 17, 2020 Celebrating 46 years of Diplomacy in Action NATIONAL COMMITTEE ON AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY 2020 VIRTUAL GALA SPONSORS Silver Sponsors Thomas S. Hexner Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in New York Bronze Sponsors John V. Connorton, Jr., Esq. Brendan R. McGuire, Esq. Richard and Elizabeth Howe Jeffrey and Mary Lou Shafer The Ronald and Jo Carole Donald and Genie Rice Lauder Foundation Donald Zagoria National Committee on American Foreign Policy Board of Trustees Honorable Jeffrey R. Shafer - Chairman of the Board Honorable Nancy E. Soderberg - Vice Chairman of the Board Ambassador (ret.) Susan M. Elliott - President and CEO Richard R. Howe, Esq. - Executive Vice President & Treasurer Donald S. Rice, Esq. - Senior Vice President Professor Donald Zagoria - Senior Vice President John V. Connorton, Jr., Esq. - Secretary Dr. George D. Schwab - President Emeritus Grace Kennan Warnecke - Chair Emeritus Honorable David Adelman - Trustee Honorable Donald M. Blinken - Trustee Andrew L. Busser - Trustee Steven Chernys - Trustee Honorable Karl W. Eikenberry - Trustee Thomas S. Hexner - Trustee Kimberly Kriger - Trustee Brendan R. McGuire, Esq.- Trustee Honorable Thomas Pickering - Trustee Nicholas R. Thompson - Trustee NATIONAL COMMITTEE ON AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY MISSION STATEMENT The National Committee on American Foreign Policy, Inc. (NCAFP) identifies, articulates, and helps advance American foreign policy interests from a nonpartisan perspective within the framework of political realism. Founded in 1974 by Professor Hans J. Morgenthau and others, the NCAFP is a nonprofit policy organization dedicated to the resolution of conflicts that threaten U.S. interests. The NCAFP fulfills its mission through Track I ⁄ and Track II diplomacy. These closed-door and off-the-record conferences provide opportunities for senior U.S. -

Kissinger: a Case Study from The

KISSINGER: A CASE STUDY FROM THE CHINESE PERSPECTIVE & PROPOSAL TO EXPAND THE AMERICAN SECRETARIES OF STATE DATA VISUALIZATION PROJECT John Ferguson Final Seminar Paper Harvard Law School 3061 Negotiation Lessons from American Secretaries of State Professors Robert Mnookin, Jim Sebenius, Nicholas Burns December 20, 2020 Table of Contents Introduction 1. Kissinger’s Humor a. Documents & Multimedia (data visualization) 2. Kissinger’s Networks a. 3D Force-Directed Graphs (data visualization) 3. Kissinger’s Canvas a. Multilevel Timeline (data visualization) Conclusion Acknowledgements Data visualization proof-of-concepts created for the preparation of this paper: All secretaries video demo (CLICK HERE) All secretaries interface (CLICK HERE) Kissinger video demo (CLICK HERE) Kissinger interface (CLICK HERE) 1 Introduction This paper is a one-half Kissinger case study and one-half proposal for the next step of the American Secretaries of State Project visualization integrated in one. Henry Kissinger’s example is used as the vehicle through which I demonstrate the utility of why and how the American Secretaries of State Project interactive visualization interface could develop and expand. Given the enormous English literature that already exists on Kissinger including Professor Sebenius, Burns, and Mnookin’s own Kissinger the Negotiator, the analysis in this paper primarily uses Chinese-language sources. After careful study of Henry Kissinger’s interviews, books, biographies, and transcripts of all types through the lens of Chinese diplomats and scholars, three specific attributes have emerged in further explaining why Henry Kissinger was arguably the most successful Secretary of State—humor, networks, and the canvas. Each attribute explanation is immediately followed by a proposal to expand the data visualization project. -

Dr. Henry Kissinger 56Th United States Secretary of State Chairman, Kissinger Associates, Inc

The Economic Club of New York 475th Meeting 110th Year ______________________________________ Dr. Henry Kissinger 56th United States Secretary of State Chairman, Kissinger Associates, Inc. ______________________________________ December 5, 2017 New York City Interviewer: Glenn Hutchins Vice Chairman, Economic Club of New York Founder, North Island Capital and Silver Lake Capital The Economic Club of New York – Dr. Henry Kissinger – December 5, 2017 Page 1 Introduction Chairman Terry J. Lundgren Welcome to the 475th meeting of the Economic Club of New York. My name is Terry Lundgren. I’m Chairman of the Economic Club and Executive Chairman of Macy’s, Inc. The Economic Club is the nation’s leading nonpartisan forum for speeches and conversations on economic, social, and political issues. More than 1,000 prominent guests have spoken before our Club over this past century. I’d like to take a moment to recognize and thank the members of the Centennial Society sitting in our front row here. Those are the individuals who have contributed more than $10,000 each to our Club and they make up the financial backbone of this organization and allow us to do so many of these events. I’d also like to welcome the students and faculty who are joining us tonight. They are from Columbia Law School, Columbia School of International and Public Affairs, Fordham Gabelli School of Business, and Manhattan College. We’re glad to have you here as always. 2017 was an important year for the Economic Club and we accomplished many things, including a record-breaking number of events and different types of events. -

Challenges and Opportunities

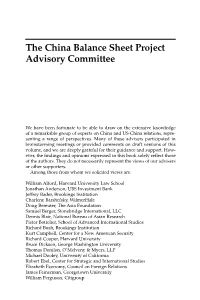

The China Balance Sheet Project Advisory Committee We have been fortunate to be able to draw on the extensive knowledge of a remarkable group of experts on China and US-China relations, repre- senting a range of perspectives. Many of these advisers participated in brainstorming meetings or provided comments on draft versions of this volume, and we are deeply grateful for their guidance and support. How- ever, the findings and opinions expressed in this book solely reflect those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of our advisers or other supporters. Among those from whom we solicited views are: William Alford, Harvard University Law School Jonathan Anderson, UBS Investment Bank Jeffrey Bader, Brookings Institution Charlene Barshefsky, WilmerHale Doug Bereuter, The Asia Foundation Samuel Berger, Stonebridge International, LLC Dennis Blair, National Bureau of Asian Research Pieter Bottelier, School of Advanced International Studies Richard Bush, Brookings Institution Kurt Campbell, Center for a New American Security Richard Cooper, Harvard University Bruce Dickson, George Washington University Thomas Donilon, O’Melveny & Myers, LLP Michael Dooley, University of California Robert Ebel, Center for Strategic and International Studies Elizabeth Economy, Council on Foreign Relations James Feinerman, Georgetown University William Ferguson, Citigroup 256 CHINA’S RISE Joseph Fewsmith, Boston University David Finkelstein, CNA Charles Freeman, Center for Strategic and International Studies Michael Gadbaw, General Electric Company, retd. Paul Gewirtz, Yale University Bonnie Glaser, Center for Strategic and International Studies Morris Goldstein, Peterson Institute for International Economics Michael Goltzman, The Coca-Cola Company Thomas Gottschalk, Kirkland & Ellis, LLP Maurice Greenberg, C.V. Starr & Company, Inc. Scott Hallford, Federal Express Carol Lee Hamrin, Global China Center Harry Harding, George Washington University Benjamin Heineman, Harvard Law School David Henson, Caterpillar Inc. -

Corporate Data and Shareholder Information

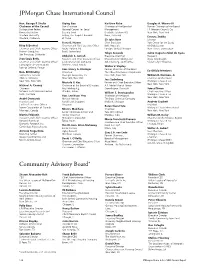

JPMorgan Chase International Council Hon. George P. Shultz Xiqing Gao Kai-Uwe Ricke Douglas A. Warner III Chairman of the Council Vice Chairman Chairman of the Board of Former Chairman of the Board Distinguished Fellow National Council for Social Management J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. Hoover Institution Security Fund Deutsche Telekom AG New York, New York Stanford University Beijing, The People’s Republic Bonn, Germany Ernesto Zedillo Stanford, California of China Sir John Rose Director Franz B. Humer Chief Executive Yale Center for the Study Riley P. Bechtel Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Rolls-Royce plc of Globalization Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Roche Holding Ltd. London, United Kingdom New Haven, Connecticut Bechtel Group, Inc. Basel, Switzerland Tokyo Sexwale Jaime Augusto Zobel de Ayala San Francisco, California Abdallah S. Jum’ah Executive Chairman President Jean-Louis Beffa President and Chief Executive Officer Mvelaphanda Holdings Ltd Ayala Corporation Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Saudi Arabian Oil Company Johannesburg, South Africa Makati City, Philippines Compagnie de Saint-Gobain Dhahran, Saudi Arabia Walter V. Shipley Paris-La Défense, France Hon. Henry A. Kissinger Former Chairman of the Board Ex-Officio Members Hon. Bill Bradley Chairman The Chase Manhattan Corporation Former U.S. Senator Kissinger Associates, Inc. New York, New York William B. Harrison, Jr. Allen & Company New York, New York Chairman of the Board Jess Søderberg New York, New York JPMorgan Chase & Co. Mustafa V. Koç Partner and Chief Executive Officer New York, New York Michael A. Chaney Chairman of the Board of Directors A.P. Møller-Maersk Group Chairman Koç Holding A.S.Ç Copenhagen, Denmark James Dimon National Australia Bank Limited Istanbul, Turkey Chief Executive Officer William S. -

FREEPORT-Mcmoran COPPER & GOLD INC. 2003 ANNUAL REPORT

THE STRENGTH OF OUR METALS FREEPORT-McMoRan COPPER & GOLD INC. FREEPORT-McMoRan COPPER & GOLD INC. 1615 POYDRAS STREET 2003 ANNUAL REPORT NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA 70112 WWW.FCX.COM FREEPORT-MCMOR AN COPPER & GOLD INC. Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold Inc. (FCX) conducts its STOCKHOLDER INFORMATION operations through its subsidiaries, PT Freeport Indonesia, PT Puncakjaya Power, PT Irja Eastern Minerals and Atlantic Copper, S.A. PT Freeport Indonesia’s operations in the INVESTOR INQUIRIES COMMON SHARE DIVIDENDS Indonesian province of Papua include exploration and The Investor Relations Department will be pleased to There were no cash dividends paid on FCX common development, mining and milling of ore containing copper, receive any inquiries about the company's securities, stock during 2002. In February 2003, the Board of including its common stock and depositary shares, or Directors authorized a new cash dividend policy for gold and silver, and the worldwide marketing of concentrates about any phase of the company's activities. A link to FCX’s common stock with the initial $0.09 per share containing those metals. PT Puncakjaya Power supplies power our Annual Report on Form 10-K filed with the Securities quarterly dividend being paid on May 1, 2003. Below to PT Freeport Indonesia’s operations. Eastern Minerals and Exchange Commission, which includes certifications is a summary of the common stock cash dividend conducts mineral exploration activities in Papua. Atlantic of our Chief Executive Officer and Chief Financial Officer declared and paid for the quarterly periods of 2003: and the company’s Ethics and Business Conduct Policy, Copper, FCX’s wholly owned subsidiary in Huelva, Spain, is available on our web site. -

Kissinger Caught in Web of Lies on BCCI Ties

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 18, Number 47, December 6, 1991 Kissinger caught in web of lies on BCCI ties by Scott Thompson EIR has obtained copies of documents which show that Dr. was Marine Midland Bank, which has been owned since Henry Kissinger and his employee Alan Stoga were deeply 1978 by the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corp., whose involved in the Bank of Credit and Commerce International involvement in illegal narcotics dates back to the 19th-centu (BCCI) scandal dating back to 1988. The documents, which ry "Opium Wars." EIR has documented extensive ties be were the basis of articles appearing in the Nov. II and 12 tween the "Hongshang" and Kissinger Associates in past Boston Globe, show that former Brazilian ambassador to the articles, but one highlight is iliat Hongshang board member U.S. Sergio Correa da Costa was chairman of BCCI Brazil Li Kai-shing ("the Red Fatdat") is believed to be a major at the same time that he was a special consultant to Kissinger financial backer for newspaper acquisitions, like the buy-up during 1986-88. One letter, from former First American of the London Daily Telegraph and the Jerusalem Post, by Bankshares chairman Clark Clifford, suggests that Kissing Conrad Black's HollingerCotp. Kissinger is a board member er's personal attorney, William D. Rogers, may have helped of Hollinger Corp. Then, the Hongshang also signed a global cover up the BCCI scandal when it first broke. merger with Midland Bank PLC, which is not only a client of Ambassador L. -

Joshua Cooper Ramo Co-CEO, Kissinger Associates, and Author of the Age of the Unthinkable and the Seventh Sense

Joshua Cooper Ramo Co-CEO, Kissinger Associates, and Author of The Age of the Unthinkable and The Seventh Sense Joshua Cooper Ramo is Co-Ceo of Kissinger Associates, the advisory firm of former U.S. Secretary of State Dr. Henry Kissinger. His last book was the international best seller, The Age Of The Unthinkable. Based in Beijing and New York, Ramo serves as an advisor to some of the largest companies and investors in the world. He is a member of the boards of directors of Starbucks and FedEx. A Mandarin speaker who has been called “one of China’s leading foreign-born scholars” by the World Economic Forum, Ramo is best known for coining and articulating “The Beijing Consensus,” among other writings on China. His views on global politics and economics have appeared in the Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, Time, Foreign Policy, and Fortune. He has been a frequent guest on CNN, CNBC, NBC, and PBS. In 2008 he served as China analyst for NBC during the Beijing Olympic Games. For his work with Bob Costas and Matt Lauer during the Opening Ceremony, Ramo shared in a Peabody and Emmy award. Before entering the advisory business, Ramo was a journalist. He was the youngest senior editor and foreign editor in the history of Time magazine, wrote more than 20 cover stories, and ultimately over- saw the magazine’s technology coverage and online activities. Ramo has been a member of the World Economic Forum’s Global Leaders for Tomorrow, The Leaders Project, The Asia Society 21 Group, a term member of the Council on Foreign Relations, a founder of the US-China Young Leaders Forum, and Crown Fellow of the Aspen Institute.