An IPAC Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alberta Hansard

Province of Alberta The 28th Legislature Third Session Alberta Hansard Tuesday, March 24, 2015 Issue 25a The Honourable Gene Zwozdesky, Speaker Legislative Assembly of Alberta The 28th Legislature Third Session Zwozdesky, Hon. Gene, Edmonton-Mill Creek (PC), Speaker Rogers, George, Leduc-Beaumont (PC), Deputy Speaker and Chair of Committees Jablonski, Mary Anne, Red Deer-North (PC), Deputy Chair of Committees Allen, Mike, Fort McMurray-Wood Buffalo (PC) Kubinec, Hon. Maureen, Barrhead-Morinville-Westlock (PC) Amery, Moe, Calgary-East (PC) Lemke, Ken, Stony Plain (PC), Anderson, Rob, Airdrie (PC) Deputy Government Whip Anglin, Joe, Rimbey-Rocky Mountain House-Sundre (Ind) Leskiw, Genia, Bonnyville-Cold Lake (PC) Barnes, Drew, Cypress-Medicine Hat (W) Luan, Jason, Calgary-Hawkwood (PC) Bhardwaj, Naresh, Edmonton-Ellerslie (PC) Lukaszuk, Thomas A., Edmonton-Castle Downs (PC) Bhullar, Hon. Manmeet Singh, Calgary-Greenway (PC) Mandel, Hon. Stephen, Edmonton-Whitemud (PC) Bikman, Gary, Cardston-Taber-Warner (PC) Mason, Brian, Edmonton-Highlands-Norwood (ND) Bilous, Deron, Edmonton-Beverly-Clareview (ND), McAllister, Bruce, Chestermere-Rocky View (PC) New Democrat Opposition Whip McDonald, Hon. Everett, Grande Prairie-Smoky (PC) Blakeman, Laurie, Edmonton-Centre (AL), McIver, Hon. Ric, Calgary-Hays (PC) Liberal Opposition House Leader McQueen, Hon. Diana, Drayton Valley-Devon (PC) Brown, Dr. Neil, QC, Calgary-Mackay-Nose Hill (PC) Notley, Rachel, Edmonton-Strathcona (ND), Calahasen, Pearl, Lesser Slave Lake (PC) Leader of the New Democrat Opposition Campbell, Hon. Robin, West Yellowhead (PC) Oberle, Hon. Frank, Peace River (PC), Cao, Wayne C.N., Calgary-Fort (PC) Deputy Government House Leader Casey, Ron, Banff-Cochrane (PC) Olesen, Cathy, Sherwood Park (PC) Cusanelli, Christine, Calgary-Currie (PC) Olson, Hon. -

The Object of Rotary Is to Encourage and Foster the Ideal of Service As A

Rotary Club of Edmonton Page 1 of 4 Tuesday, September 01, 2009 Editor: Russ Mann Print this bulletin for future reference If you have any comments or questions, email the editor. 1 Future Speakers Rotary News Sep 7 2009 Remember that Monday September is a Stat holiday, sooooo no Rotary meeting. Stat Holiday - Meeting Cancelled The Object of Rotary Sep 14 2009 Fred Horne, Chair Alta Health Policy Committee The Object of Rotary is to Sep 21 2009 encourage and foster the ideal of Vikram Seth "Rotaract Project and Trip to service as a basis of worthy Kenya" enterprise and, in particular, to Oct 5 2009 encourage and foster: Lynn Sutherland, VP VrSTORM "From the Web to the Clouds" FIRST. The development of acquaintance as an opportunity for service; Oct 12 2009 SECOND. High ethical standards in business and professions, the Stat Holiday - Meeting recognition of the worthiness of all useful occupations, and the Cancelled dignifying of each Rotarian's occupation as an opportunity to serve Oct 19 2009 society; THIRD. The application of the ideal of service in each Rotarian's Hon. Heather Klimchuk, personal, business, and community life; Minister of Service Alberta FOURTH. The advancement of international understanding, goodwill, Oct 26 2009 and peace through a world fellowship of business and professional Rotarian Julie Mulligan persons united in the ideal of service. "Experiance as a kidnap victim" Rotary Program Monday September 14 Upcoming Events World Community Service The program will feature Fred Horne, Chair of the Alberta Committee Heath Policy Committee Sep 11 2009 - Sep 11 2009 Youth Service Committee meeting Fred Horne (born August 25, 1961 in Whitby, Ontario) is a Sep 14 2009 - Sep 14 2009 Canadian politician and current Member of the Legislative Assembly of Alberta representing the constituency of http://www.clubrunner.ca/CPrg/Bulletin/SendBulletinEmail.aspx?cid=447 9/1/2009 Rotary Club of Edmonton Page 2 of 4 This eBulletin has been Edmonton-Rutherford as a Progressive Conservative. -

Premier Stelmach Sets out Priorities; Names New Cabinet, Reorganizes Portfolios Changes to Government Structure Reflect Government Priorities

March 12, 2008 Premier Stelmach sets out priorities; names new Cabinet, reorganizes portfolios Changes to government structure reflect government priorities Edmonton... Premier Ed Stelmach has laid out the priorities for his new administration, reorganizing portfolios and adding four new ministries. The Premier also named his new Cabinet which features new faces and new assignments for previous members, and introduces the role of parliamentary assistants who will help support ministers on key projects. "This Cabinet and new government structure will focus on building a stronger Alberta and improving the lives of Albertans,” said Premier Stelmach. “The Cabinet team balances experience and new perspectives and is well skilled for the work ahead.” The new Cabinet will be focused on five priorities: ensuring Alberta’s energy resources are developed in an environmentally sustainable way; increasing access to quality health care and improving the efficiency and effectiveness of health care service delivery; enhancing value-added activity, increasing innovation, and improving the long-run sustainability of Alberta’s economy; reducing crime so Albertans feel safe in their communities; and providing the roads, schools, hospitals and other public infrastructure to meet the needs of a growing economy and population. Changes to the government structure will help better meet these priorities. Government’s increased focus on culture is reflected in the new Ministry of Culture and Community Spirit which also has responsibility for the voluntary sector and the Human Rights Commission. The new Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs will help fulfill government’s plan to ensure affordable housing is available to all Albertans and to address emerging urban issues. -

The Warmth of Women's Voices by Erin Ottosen

The warmth of women’s voices by Erin Ottosen First fundraiser for Alberta Women’s Memory Project a success Joy and elation filled the TELUS Centre in Edmonton on November 15, The event resulted in generous donations of services, products and cash when the Alberta Women’s Memory Project (AWMP) held its inaugural from individuals, corporations, AU and the University of Alberta, all of fundraiser, A Celebration of Women’s Voices from the Past to which will be used to create an initial AWMP operating fund, says Jean the Future. Crozier, a member of the project committee. After noshing in the gallery for an hour or so, the audience of almost “Regardless of how much money we brought in through the fundraiser, 200 listened attentively as the Hon. Heather Klimchuk, Alberta minister I really think the big plus is that now a lot more people know about us,” of culture and community services, brought greetings from Premier she continues. “Women’s memories — captured through their artifacts Alison Redford and the guest speakers, Edmonton Journal columnist — have not always been regarded with much respect. Too often, these Paula Simons and breast cancer surgeon Dr. Kelly Dabbs, shared stories materials were destroyed when a woman died. As a result, we’ve had from their lives about working and living in Alberta. few sources of materials to study and from which to understand the “The energy at the event was wonderful,” says Jim McLeod, AU viewpoints of Alberta women, the contributions they’ve made to this manager of community relations and events. “You could tell people province and their influence on our society and our history.” were truly excited about the project and what it’s accomplishing in “We are very grateful to Athabasca University, the University of Alberta, terms of documenting the history of Alberta women. -

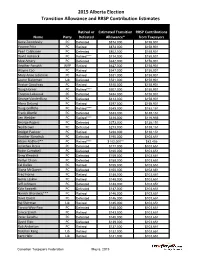

2015 Alberta Election Transition Allowance and RRSP Contribution Estimates

2015 Alberta Election Transition Allowance and RRSP Contribution Estimates Retired or Estimated Transition RRSP Contributions Name Party Defeated Allowance* from Taxpayers Gene Zwozdesky PC Defeated $874,000 $158,901 Yvonne Fritz PC Retired $873,000 $158,901 Pearl Calahasen PC Defeated $802,000 $158,901 David Hancock PC Retired**** $714,000 $158,901 Moe Amery PC Defeated $642,000 $158,901 Heather Forsyth WRP Retired $627,000 $158,901 Wayne Cao PC Retired $547,000 $158,901 Mary Anne Jablonski PC Retired $531,000 $158,901 Laurie Blakeman Lib Defeated $531,000 $158,901 Hector Goudreau PC Retired $515,000 $158,901 Doug Horner PC Retired**** $507,000 $158,901 Thomas Lukaszuk PC Defeated $484,000 $158,901 George VanderBurg PC Defeated $413,000 $158,901 Alana DeLong PC Retired $397,000 $158,901 Doug Griffiths PC Retired**** $349,000 $152,151 Frank Oberle PC Defeated $333,000 $138,151 Len Webber PC Retired**** $318,000 $116,956 George Rogers PC Defeated $273,000 $138,151 Neil Brown PC Defeated $273,000 $138,151 Bridget Pastoor PC Retired $238,000 $138,151 Heather Klimchuk PC Defeated $195,000 $103,651 Alison Redford** PC Retired**** $182,000** $82,456 Jonathan Denis PC Defeated $177,000 $103,651 Robin Campbell PC Defeated $160,000 $103,651 Greg Weadick PC Defeated $159,000 $103,651 Verlyn Olson PC Defeated $158,000 $103,651 Cal Dallas PC Retired $155,000 $103,651 Diana McQueen PC Defeated $150,000 $103,651 Fred Horne PC Retired $148,000 $103,651 Genia Leskiw PC Retired $148,000 $103,651 Jeff Johnson PC Defeated $148,000 $103,651 Kyle Fawcett -

The Alberta Gazette

The Alberta Gazette Part I Vol. 110 Edmonton, Monday, March 31, 2014 No. 06 PROCLAMATION [GREAT SEAL] CANADA PROVINCE OF ALBERTA Donald S. Ethell, Lieutenant Governor. ELIZABETH THE SECOND, by the Grace of God, of the United Kingdom, Canada, and Her Other Realms and Territories, QUEEN, Head of the Commonwealth, Defender of the Faith P R O C L A M A T I O N To all to Whom these Presents shall come G R E E T I N G Kim Armstrong Deputy Attorney General WHEREAS section 2(3) of the Statutes Amendment Act, 2013 (No. 2) provides that section 2 of that Act comes into force on Proclamation; and WHEREAS it is expedient to proclaim section 2 of the Statutes Amendment Act, 2013 (No. 2) in force: NOW KNOW YE THAT by and with the advice and consent of Our Executive Council of Our Province of Alberta, by virtue of the provisions of the said Act hereinbefore referred to and of all other power and authority whatsoever in Us vested in that behalf, We have ordered and declared and do hereby proclaim section 2 of the Statutes Amendment Act, 2013 (No. 2) in force on April 1, 2014. IN TESTIMONY WHEREOF We have caused these Our Letters to be made Patent and the Great Seal of Our Province of Alberta to be hereunto affixed. WITNESS: COLONEL (RETIRED) THE HONOURABLE DONALD S. th ETHELL, Lieutenant Governor of Our Province of Alberta, this 12 day of March in the Year of Our Lord Two Thousand Fourteen and in the Sixty-third Year of Our Reign. -

Legislative Reports

Legislative Reports government’s budget for not shar- evening. Even a brief power outage ing the $1.3 billion resources with that dimmed the lights in the As- average Saskatchewan families. The sembly did not curtail his stamina NDP identified four areas that to continue. Mr. Yates concluded could have been addressed, includ- his remarks by moving an amend- ing immediately doubling property ment to extend the sitting hours to tax relief, doubling the number of 1:00 a.m. on Mondays, Tuesdays new training seats, investing in af- and Wednesdays. fordable housing programs and The Opposition’s successful ef- funding green initiatives to help the forts to delay implementation of the Saskatchewan province meet its climate change extended sitting hours prompted targets. the Government to give notice of he Assembly returned for a Thebudgetdebatewascon- their intent to move closure on the Tshortened spring session on cluded on April 3rd with the As- motion at the earliest opportunity March 10th. Members first paused sembly defeating the Opposition on April 8th. The Opposition House to reflect on the passing of nine for- amendment and adopting the bud- Leader Len Taylor responded by mer Members over the previous get motion. raising a question of privilege on year and to adopt motions of condo- the decision to invoke closure. The Extended Hours Motions lence for each. Subsequent days basis of his submission was that were devoted to considering sup- changes to the standing orders of After growing concerned that there plementary estimates and moving parliaments were traditionally only were insufficient sitting hours to forward on the government’s legis- implemented after opposition par- complete its agenda before the lative agenda. -

P:\HANADMIN\BOUND\Committees

Legislative Assembly of Alberta The 27th Legislature Third Session Standing Committee on Public Safety and Services Department of Service Alberta Consideration of Main Estimates Wednesday, February 17, 2010 6:31 p.m. Transcript No. 27-3-2 Legislative Assembly of Alberta The 27th Legislature Third Session Standing Committee on Public Safety and Services Drysdale, Wayne, Grande Prairie-Wapiti (PC), Chair Kang, Darshan S., Calgary-McCall (AL), Deputy Chair MacDonald, Hugh, Edmonton-Gold Bar (AL), Acting Deputy Chair, February 17, 2010 Boutilier, Guy C., Fort McMurray-Wood Buffalo (Ind) Brown, Dr. Neil, QC, Calgary-Nose Hill (PC) Calahasen, Pearl, Lesser Slave Lake (PC) Cao, Wayne C.N., Calgary-Fort (PC) Forsyth, Heather, Calgary-Fish Creek (WA) Griffiths, Doug, Battle River-Wainwright (PC) MacDonald, Hugh, Edmonton-Gold Bar (AL) Rogers, George, Leduc-Beaumont-Devon (PC) Sandhu, Peter, Edmonton-Manning (PC) Xiao, David H., Edmonton-McClung (PC) Department of Service Alberta Participant Hon. Heather Klimchuk Minister Support Staff W.J. David McNeil Clerk Louise J. Kamuchik Clerk Assistant/Director of House Services Micheline S. Gravel Clerk of Journals/Table Research Robert H. Reynolds, QC Senior Parliamentary Counsel Shannon Dean Senior Parliamentary Counsel Corinne Dacyshyn Committee Clerk Jody Rempel Committee Clerk Karen Sawchuk Committee Clerk Rhonda Sorensen Manager of Communications Services Melanie Friesacher Communications Consultant Tracey Sales Communications Consultant Philip Massolin Committee Research Co-ordinator Stephanie LeBlanc Legal Research Officer Diana Staley Research Officer Rachel Stein Research Officer Liz Sim Managing Editor of Alberta Hansard Transcript produced by Alberta Hansard February 17, 2010 Public Safety and Services PS-193 6:31 p.m. Wednesday, February 17, 2010 Committee members, ministers, and other members who are not Title: Wednesday, February 17, 2010 PS committee members may participate. -

Premier Promotes Verlyn Olson and Greg Weadick to Cabinet Cal Dallas Becomes the New Parliamentary Assistant to Finance

February 17, 2011 Premier promotes Verlyn Olson and Greg Weadick to cabinet Cal Dallas becomes the new Parliamentary Assistant to Finance Edmonton... Premier Ed Stelmach announced today that Wetaskiwin-Camrose MLA Verlyn Olson, QC, has been named Minister of Justice and Attorney General, and Lethbridge West MLA Greg Weadick has been named Minister of Advanced Education and Technology. “I’m pleased to welcome Verlyn and Greg to the cabinet table,” said Premier Stelmach. “Verlyn and Greg bring the necessary talent and experience - Greg as a parliamentary assistant and Verlyn as a long-time member of the bar - to complete our cabinet team. Our cabinet will continue to provide the steady leadership required right now to continue building a better Alberta.” Premier Stelmach also named a new Parliamentary Assistant to the Minister of Finance and Enterprise. “I’m pleased that Red Deer South MLA Cal Dallas, who had been serving as the Parliamentary Assistant in Environment, will take over this important role and work closely with Finance Minister Lloyd Snelgrove,” said the Premier. Premier Stelmach also announced changes to committee memberships. Joining the Agenda and Priorities Committee are Sustainable Resource Development Minister Mel Knight, Children and Youth Services Minister Yvonne Fritz and Agriculture and Rural Development Minister Jack Hayden. New members of Treasury Board are Len Webber, Minister of Aboriginal Relations, Heather Klimchuk, Minister of Service Alberta, and Naresh Bhardwaj, MLA for Edmonton-Ellerslie. The new Cabinet members will be sworn in Friday, February 18 at 8:30 a.m. at Government House. Lloyd Snelgrove was sworn in as Minister of Finance and Enterprise on January 31. -

Alberta Hansard

Province of Alberta The 28th Legislature First Session Alberta Hansard Thursday, November 1, 2012 Issue 13a The Honourable Gene Zwozdesky, Speaker Legislative Assembly of Alberta The 28th Legislature First Session Zwozdesky, Hon. Gene, Edmonton-Mill Creek (PC), Speaker Rogers, George, Leduc-Beaumont (PC), Deputy Speaker and Chair of Committees Jablonski, Mary Anne, Red Deer-North (PC), Deputy Chair of Committees Allen, Mike, Fort McMurray-Wood Buffalo (PC) Khan, Hon. Stephen, St. Albert (PC) Amery, Moe, Calgary-East (PC) Klimchuk, Hon. Heather, Edmonton-Glenora (PC) Anderson, Rob, Airdrie (W), Kubinec, Maureen, Barrhead-Morinville-Westlock (PC) Official Opposition House Leader Lemke, Ken, Stony Plain (PC) Anglin, Joe, Rimbey-Rocky Mountain House-Sundre (W) Leskiw, Genia, Bonnyville-Cold Lake (PC) Barnes, Drew, Cypress-Medicine Hat (W) Luan, Jason, Calgary-Hawkwood (PC) Bhardwaj, Naresh, Edmonton-Ellerslie (PC) Lukaszuk, Hon. Thomas A., Edmonton-Castle Downs (PC) Bhullar, Hon. Manmeet Singh, Calgary-Greenway (PC) Mason, Brian, Edmonton-Highlands-Norwood (ND), Bikman, Gary, Cardston-Taber-Warner (W) Leader of the New Democrat Opposition Bilous, Deron, Edmonton-Beverly-Clareview (ND) McAllister, Bruce, Chestermere-Rocky View (W), Blakeman, Laurie, Edmonton-Centre (AL), Official Opposition Deputy Whip Liberal Opposition House Leader McDonald, Everett, Grande Prairie-Smoky (PC) Brown, Dr. Neil, QC, Calgary-Mackay-Nose Hill (PC) McIver, Hon. Ric, Calgary-Hays (PC), Calahasen, Pearl, Lesser Slave Lake (PC) Deputy Government House Leader Campbell, Hon. Robin, West Yellowhead (PC), McQueen, Hon. Diana, Drayton Valley-Devon (PC) Deputy Government House Leader Notley, Rachel, Edmonton-Strathcona (ND), Cao, Wayne C.N., Calgary-Fort (PC) New Democrat Opposition House Leader Casey, Ron, Banff-Cochrane (PC) Oberle, Hon. -

Alberta Hansard

Province of Alberta The 27th Legislature Fourth Session Alberta Hansard Tuesday, February 22, 2011 Issue 1 The Honourable Kenneth R. Kowalski, Speaker Legislative Assembly of Alberta The 27th Legislature Fourth Session Kowalski, Hon. Ken, Barrhead-Morinville-Westlock, Speaker Cao, Wayne C.N., Calgary-Fort, Deputy Speaker and Chair of Committees Mitzel, Len, Cypress-Medicine Hat, Deputy Chair of Committees Ady, Hon. Cindy, Calgary-Shaw (PC) Kang, Darshan S., Calgary-McCall (AL) Allred, Ken, St. Albert (PC) Klimchuk, Hon. Heather, Edmonton-Glenora (PC) Amery, Moe, Calgary-East (PC) Knight, Hon. Mel, Grande Prairie-Smoky (PC) Anderson, Rob, Airdrie-Chestermere (WA), Leskiw, Genia, Bonnyville-Cold Lake (PC) WA Opposition House Leader Liepert, Hon. Ron, Calgary-West (PC) Benito, Carl, Edmonton-Mill Woods (PC) Lindsay, Fred, Stony Plain (PC) Berger, Evan, Livingstone-Macleod (PC) Lukaszuk, Hon. Thomas A., Edmonton-Castle Downs (PC), Bhardwaj, Naresh, Edmonton-Ellerslie (PC) Deputy Government House Leader Bhullar, Manmeet Singh, Calgary-Montrose (PC) Lund, Ty, Rocky Mountain House (PC) Blackett, Hon. Lindsay, Calgary-North West (PC) MacDonald, Hugh, Edmonton-Gold Bar (AL) Blakeman, Laurie, Edmonton-Centre (AL), Marz, Richard, Olds-Didsbury-Three Hills (PC) Official Opposition Deputy Leader, Mason, Brian, Edmonton-Highlands-Norwood (ND), Official Opposition House Leader Leader of the ND Opposition Boutilier, Guy C., Fort McMurray-Wood Buffalo (WA) McFarland, Barry, Little Bow (PC) Brown, Dr. Neil, QC, Calgary-Nose Hill (PC) McQueen, Diana, Drayton Valley-Calmar (PC) Calahasen, Pearl, Lesser Slave Lake (PC) Morton, F.L., Foothills-Rocky View (PC) Campbell, Robin, West Yellowhead (PC), Notley, Rachel, Edmonton-Strathcona (ND), Government Whip ND Opposition House Leader Chase, Harry B., Calgary-Varsity (AL), Oberle, Hon. -

Alberta Hansard

Province of Alberta The 27th Legislature Fifth Session Alberta Hansard Tuesday, February 7, 2012 Issue 1 The Honourable Kenneth R. Kowalski, Speaker Legislative Assembly of Alberta The 27th Legislature Fifth Session Kowalski, Hon. Ken, Barrhead-Morinville-Westlock, Speaker Cao, Wayne C.N., Calgary-Fort, Deputy Speaker and Chair of Committees Zwozdesky, Gene, Edmonton-Mill Creek, Deputy Chair of Committees Ady, Cindy, Calgary-Shaw (PC) Kang, Darshan S., Calgary-McCall (AL), Allred, Ken, St. Albert (PC) Official Opposition Whip Amery, Moe, Calgary-East (PC) Klimchuk, Hon. Heather, Edmonton-Glenora (PC) Anderson, Rob, Airdrie-Chestermere (W), Knight, Mel, Grande Prairie-Smoky (PC) Wildrose Opposition House Leader Leskiw, Genia, Bonnyville-Cold Lake (PC) Benito, Carl, Edmonton-Mill Woods (PC) Liepert, Hon. Ron, Calgary-West (PC) Berger, Hon. Evan, Livingstone-Macleod (PC) Lindsay, Fred, Stony Plain (PC) Bhardwaj, Naresh, Edmonton-Ellerslie (PC) Lukaszuk, Hon. Thomas A., Edmonton-Castle Downs (PC) Bhullar, Hon. Manmeet Singh, Calgary-Montrose (PC) Lund, Ty, Rocky Mountain House (PC) Blackett, Lindsay, Calgary-North West (PC) MacDonald, Hugh, Edmonton-Gold Bar (AL) Blakeman, Laurie, Edmonton-Centre (AL), Marz, Richard, Olds-Didsbury-Three Hills (PC) Official Opposition Deputy Leader, Mason, Brian, Edmonton-Highlands-Norwood (ND), Official Opposition House Leader Leader of the ND Opposition Boutilier, Guy C., Fort McMurray-Wood Buffalo (W) McFarland, Barry, Little Bow (PC) Brown, Dr. Neil, QC, Calgary-Nose Hill (PC) McQueen, Hon. Diana, Drayton Valley-Calmar (PC) Calahasen, Pearl, Lesser Slave Lake (PC) Mitzel, Len, Cypress-Medicine Hat (PC) Campbell, Robin, West Yellowhead (PC), Morton, Hon. F.L., Foothills-Rocky View (PC) Government Whip Notley, Rachel, Edmonton-Strathcona (ND), Chase, Harry B., Calgary-Varsity (AL) ND Opposition House Leader Dallas, Hon.