Ginosko21.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wavebid > Buyers Guide

Auction Catalog March 2021 Auction Auction Date: Sunday, Feb 28 2021 Bidding Starts: 12:00 PM EST Granny's Auction House Phone: (727) 572-1567 5175 Ulmerton Rd Email: grannysauction@gmail. Ste B com Clearwater, FL 33760 © 2021 Granny's Auction House 02/28/2021 07:36 AM Lot Title & Description Number 12" x 16" Wyland Lucite Limited Edition Orca Family Statue - Free form clear lucite form reminiscent of ice with sun softened edges 1 holding family pod of 3 Orcas/ killer whales, etched Wyland signature lower left, numbered 105/950 lower right - in house shipping available 2 6" x 4" Russian Lacquerware Box Signed and Numbered with Mythic Cavalry Scene - Black Ground, Bright Red Interior - In House Shipping Available Tiffany & Co. Makers Sterling Silver 6 1/2" plate - 16052 A, 7142, 925-1000, beautiful rimmed plate. 5.095 ozt {in house shipping 3 available} 2 Disney Figurines With Original Boxes & COA - My Little Bambi and Mothe # 14976 & Mushroom Dancer Fantasia. {in house shipping 4 available} 2 Art Glass Paperweights incl. Buccaneers Super Bowl Football - Waterford crystal Super Bowl 37 Buccaneers football #1691/2003 & 5 Murano with copper fleck (both in great condition) {in house shipping available} 6 Hard to Find Victor "His Master's Voice" Neon Sign - AAA Sign Company, Coltsville Ohio (completely working) {local pick up or buyer arranges third party shipping} 7 14K Rose Gold Ring With 11ct Smokey Topaz Cut Stone - size 6 {in house shipping available} 8 5 200-D NGC Millennium Set MS 67 PL Sacagawea Dollar Coins - Slabbed and Graded by NGC, in house shipping available Elsa de Bruycker Oil on Canvas Panting of Pink Cadillac Flying in to the distance - Surrealilst image of cadillac floating above the road 9 in bright retro style, included is folio for Elsa's Freedom For All Statue of Liberty Series - 25" x 23" canvas, framed 29" x 28" local pick up and in house shipping available 10 1887 French Gilt Bronze & Enamel Pendent Hanging Lamp - Signed Emile Jaud Et Jeanne Aubert 17 Mai 1887, electrified. -

Antigua's Superyacht

On-line FEBRUARY 2008 NO. 149 The Caribbean’s Monthly Look at Sea & Shore Antigua’s Superyacht Cup See story on page 13 © KOS/KOSPICTURES.COM FEBRUARY 2008 CARIBBEAN COMPASS PAGE 2 FEBRUARY 2008 CARIBBEAN COMPASS PAGE 3 CALENDAR FEBRUARY 2 - 4 Martinique Carnival Regatta. Club Nautique Le Neptune (CNN), [email protected], www.clubnautiqueleneptune.com 3 - 6 Carnival Monday and Tuesday in most Dutch and French islands, Puerto Rico, Dominica, Carriacou, Trinidad & Tobago, Venezuela, and other places The Caribbean’s Monthly Look at Sea & Shore 7 Independence Day. Public holiday in Grenada 9 - 10 St. Croix International Regatta. St. Croix Yacht Club (SCYC), www.caribbeancompass.com www.stcroixyc.com 13 - 17 Casa de Campo Regatta, Dominican Republic. FEBRUARY 2008 • NUMBER 149 www.casadecamporegatta.com 15 - 17 30th Annual Sweethearts of the Caribbean and 26th Annual Classic Yacht Regatta, Tortola. West End Yacht Club (WEYC), [email protected], www.weyc.net Bombs Away! 17 Sailors’ and Landlubbers’ Auction, Bequia. (784) 457-3047 Visiting Vieques.....................24 18 Presidents’ Day. Public holiday in Puerto Rico and USVI 20 Lunar Eclipse visible throughout the Caribbean 21 FULL MOON 21 - 24 Grenada Classic Yacht Regatta. www.ClassicRegatta.com 22 Independence Day. Public holiday in St. Lucia. Yacht races 24 Bonaire International Fishing Tournament. www.infobonaire.com 27 Independence Day. Public holiday in Dominican Republic TBA Non-Stop Around Martinique Race. CNN TBA Semaine Nautique Schoelcher, Martinique. [email protected] Small Island… …big launching! ....................17 MARCH Labor of Love 1 Spanish Town Fishermen’s Jamboree and 12th Annual Plastic classic renewed ..........18 Wahoo Tournament, BVI 3 H. -

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020 1 REGA PLANAR 3 TURNTABLE. A Rega Planar 3 8 ASSORTED INDIE/PUNK MEMORABILIA. turntable with Pro-Ject Phono box. £200.00 - Approximately 140 items to include: a Morrissey £300.00 Suedehead cassette tape (TCPOP 1618), a ticket 2 TECHNICS. Five items to include a Technics for Joe Strummer & Mescaleros at M.E.N. in Graphic Equalizer SH-8038, a Technics Stereo 2000, The Beta Band The Three E.P.'s set of 3 Cassette Deck RS-BX707, a Technics CD Player symbol window stickers, Lou Reed Fan Club SL-PG500A CD Player, a Columbia phonograph promotional sticker, Rock 'N' Roll Comics: R.E.M., player and a Sharp CP-304 speaker. £50.00 - Freak Brothers comic, a Mercenary Skank 1982 £80.00 A4 poster, a set of Kevin Cummins Archive 1: Liverpool postcards, some promo photographs to 3 ROKSAN XERXES TURNTABLE. A Roksan include: The Wedding Present, Teenage Fanclub, Xerxes turntable with Artemis tonearm. Includes The Grids, Flaming Lips, Lemonheads, all composite parts as issued, in original Therapy?The Wildhearts, The Playn Jayn, Ween, packaging and box. £500.00 - £800.00 72 repro Stone Roses/Inspiral Carpets 4 TECHNICS SU-8099K. A Technics Stereo photographs, a Global Underground promo pack Integrated Amplifier with cables. From the (luggage tag, sweets, soap, keyring bottle opener collection of former 10CC manager and music etc.), a Michael Jackson standee, a Universal industry veteran Ric Dixon - this is possibly a Studios Bates Motel promo shower cap, a prototype or one off model, with no information on Radiohead 'Meeting People Is Easy 10 Min Clip this specific serial number available. -

Chicago Was a Key R&B and Blues

By Harry Weinger h e g r e a te st h a r m o n y g r o u p o p ment,” “Pain in My Heart” and original all time, the Dells thrilled au versions of “Oh W hat a Nile” and “Stay diences with their amazing in My Comer.” After the Dells survived vocal interplay, between the a nasty car accident in 1958, their perse gruff, exp lore voice of Mar verance became a trademark. During vin Junior and the keening their early down periods, they carried on high tenor of Johnny Carter, thatwith sweet- innumerable gigs that connected T the dots of postwar black American- homeChicago blend mediated by Mickey McGill and Veme Allison, and music history: schooling from Harvey the talking bass voice from Chuck Fuqua, studio direction from Willie Barksdale. Their style formed the tem Dixon and Quincy Jones, singing back plate for every singing group that came grounds for Dinah Washington and Bar after them. They’ve been recording and bara Lewis (“Hello Stranger”) and tours touring together for more than fifty with Ray Charles. years, with merely one lineup change: A faithful Phil Chess helped the Dells Carter, formerly ©f the Flamingos reinvigorate their career in 1967. By the (t ool Hall of Fame inductees), replaced end of the sixties, they had enough clas Johnny Funches in i960. sics on Cadet/Chess - including “There Patience and camaraderie helped the Is,” “Always Together,” “I Can Sing a Dills stay the course. Starting out in the Rainbow/Love Is Blue” and brilliant Chicago suburb of Harvey, Illinois, in remakes of “Stay in My Comer” and “Oh, 1953, recording for Chess subsidiaries What a Night” (with a slight variation in Checker and Cadet and then Vee-Jay, the its title) - to make them R&B chart leg Dells had attained Hall of Fame merit by ends. -

Elizabeth Bishop's New York Notebook, 1934-1937 Loretta Blasko

What It Means To Be Modem: Elizabeth Bishop’s New York Notebook, 1934-1937 Loretta Blasko Presented to the American Culture Faculty at the University of Michigan-Flint in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Masters of Liberal Studies in American Culture May 4, 2006 First Reader Second Reader, Blasko ii Acknowledgements A special thanks to: Sandra Barry of Halifax, Nova Scotia, for your knowledge in all things E.B. and your encouragement; Susan Fleming of Flint, Michigan, for your friendship and going the distance with me; Dr. J. Zeff and Dr. J. Furman, for your patience and guidance; Andrew Manser of Chicago, Kevin Blasko and Katherine Blasko of Holly, Michigan, my children, for pushing me forward; Alice Ann Sterling Manser, my mother, for your love and support. Blasko Contents Acknowledgements, ii Forward, vi Introduction, x Part I 1934 Chapter 1. The Water That Subdues, 1 Cuttyhunk Island. Chapter 2. It Came to Her Suddenly , 9 New York, Boris Goudinov , Faust , The House o f Greed. Chapter 3. Spring Lobsters, 20 The Aquarium, the gem room at the Museum of Natural Science, Hart Crane’s “Essay Modem Poetry,” Wilenski’s The Modern Movement in Art, John Dryden’s plays. Chapter 4. The Captive Bushmaster, 34 Marianne Moore’s “The Frigate Pelican,” Coleridge’s Biographia Literaria, and Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises . Chapter 5. That Face Needs a Penny Piece of Candy, 54 Henry James’s Wings o f the Dove, What Maisie Knew, and A Small Boy and Others, The U.S.A. School of Writing, Salvador Dali. Blasko Part II 1935 Chapter 6. -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Blitz Magazine Issue 51 from March 1987

MARCH 1987 No.51 £1.10 Raymond Carver Gang Warfare Rupert Everett The Snap Pack Paul Morley on TV Oliver Reed Cybill Shepherd Peter Cook 4 Front: What's Happening 4 Dennis Hopper, Films On Four 6 Isadora Duncan, The Model Gallery 8 Marilyn Monroe, McDonald's, London Daily News 10 Condom Wars, Wranglers 40th Anniversary 12 Lost in America 14 Print 14 Ramsey Campbell, Paperback Choice 15 New Fiction, New Non-fiction 16 Film 16 New Releases 18 On 'Release Cover star Rupert 22 Television Everett, film actor 22 Paul Morley on The Box soon to turn pop 23 Video Reviews singer. 24 Music BLITZ MAGAZINE 24 The Bodines I LOWER JAMES STREET 26 Album Reviews, New Product LONDON WI R 3PN 28 Dancefloor Tel: (01) 734 nil 30 Oliver Reed: another drink, another film, by Mark Brennan PUBLISHER Carey Labovitch 34 Fashion: what a catastrophe MANAGING EDITOR Simon Tesler EDITOR Tim Hulse 40 La Vida Loca: gang warfare in the FASHION EDITOR Iain R. Webb LA barrio, by Laura Whitcomb DESIGNER Jeremy Leslie 46 Fashion: y viva espagna ADVERTISING MANAGER Cherry Austin 48 Rupert Everett: on becoming a GENERAL ASSISTANT Sarah Currie popstar, by Fiona Russell Powell FASHION ASSISTANT Darryl Black 54 Whaling: bloodsport in the Faroe CONTRIBUTORS Fenton Bailey, Tony Islands, by Steve James Barratt, Martine Baronti, Robin Barton, Mark Bayley, Malcolm Bennett, Mark 56 Cybill Shepherd: the fall and rise of Brennan, Peter Brown, Gillian Campbell, Mark Cordery, Richard Croft, Andy Darling, Bruce Dessau, Steve Double, Simon Garfield, Richard Grant, John Hind, David a Moonlighting star, by Hil lmy Hiscock, Philip Hoare, Mark Honigsbaum, Caroline Houghton, Aidan Hughes, Marc Johnson Issue, Steve James, Dave Kendall, Jeremy Lewis, Mark Lewis, Judy Lipsey, Elise 62 Fashion: the newest romantic of all Maiberger. -

Praise for Say Goodbye

praise for say goodbye “Shiner has written a fine novel about rock ’n’ roll by believing more in musicians’ human nature than in their mythologies.” —Mark Athitakis, New York Times Book Review “Say Goodbye resonates like a blue note heard and remem- bered in a smoky, late-night club. Lewis Shiner has written the Citizen Kane of rock and roll novels, a human and mov- ing piece of work.” —George P. Pelecanos, author of The Sweet Forever “Gritty, funny, cynical, and sentimental; a sharply focused epic that brings welcome revision to the sunny, pop-culture success gospels that have led so many naïve talents astray.” —Kirkus Reviews “Every band has an inner momentum like this, its entangles and wreck-tangles, moments of bliss mixed with the jar- ring reality of life in the belly of the music business, and the shared song which makes it all worthwhile. Lewis Shiner sings the tale with harmonic compassion.” —Lenny Kaye, guitarist, Patti Smith Group “Engrossing...Shiner competently vivifies the uncertainties and boredom of the musician’s life, but more impressively, he manages to convey the almost indescribable joy of bringing an audience from a state of apathy to the edge of hysteria...A revealing look at today’s music business.” —George Needham, Booklist “A spare and remarkable book resonating with heart and bittersweet reality.” —Mike Shea, Texas Monthly “[A] soulful elegy...fresh and original...Shiner’s extensive research gives the story an authentic feel and keeps it from becoming a soap opera or a wearisome cover version of every other rise-and-fall parable. -

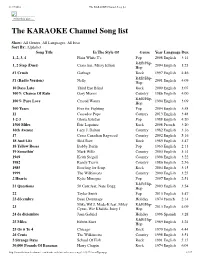

The KARAOKE Channel Song List

11/17/2016 The KARAOKE Channel Song list Print this List ... The KARAOKE Channel Song list Show: All Genres, All Languages, All Eras Sort By: Alphabet Song Title In The Style Of Genre Year Language Dur. 1, 2, 3, 4 Plain White T's Pop 2008 English 3:14 R&B/Hip- 1, 2 Step (Duet) Ciara feat. Missy Elliott 2004 English 3:23 Hop #1 Crush Garbage Rock 1997 English 4:46 R&B/Hip- #1 (Radio Version) Nelly 2001 English 4:09 Hop 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind Rock 2000 English 3:07 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris Country 1986 English 4:00 R&B/Hip- 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 1994 English 3:09 Hop 100 Years Five for Fighting Pop 2004 English 3:58 11 Cassadee Pope Country 2013 English 3:48 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan Pop 1988 English 4:20 1500 Miles Éric Lapointe Rock 2008 French 3:20 16th Avenue Lacy J. Dalton Country 1982 English 3:16 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed Country 2002 English 5:16 18 And Life Skid Row Rock 1989 English 3:47 18 Yellow Roses Bobby Darin Pop 1963 English 2:13 19 Somethin' Mark Wills Country 2003 English 3:14 1969 Keith Stegall Country 1996 English 3:22 1982 Randy Travis Country 1986 English 2:56 1985 Bowling for Soup Rock 2004 English 3:15 1999 The Wilkinsons Country 2000 English 3:25 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue Pop 2007 English 2:51 R&B/Hip- 21 Questions 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg 2003 English 3:54 Hop 22 Taylor Swift Pop 2013 English 3:47 23 décembre Beau Dommage Holiday 1974 French 2:14 Mike WiLL Made-It feat. -

Artist Song Album Blue Collar Down to the Line Four Wheel Drive

Artist Song Album (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Blue Collar Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Down To The Line Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Four Wheel Drive Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Free Wheelin' Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Gimme Your Money Please Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Hey You Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Let It Ride Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Lookin' Out For #1 Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Roll On Down The Highway Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Take It Like A Man Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Takin' Care Of Business Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive You Ain't Seen Nothing Yet Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Takin' Care Of Business Hits of 1974 (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive You Ain't Seen Nothin' Yet Hits of 1974 (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Can't Get It Out Of My Head Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Evil Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Livin' Thing Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Ma-Ma-Ma Belle Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Mr. Blue Sky Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Rockaria Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Showdown Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Strange Magic Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Sweet Talkin' Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Telephone Line Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Turn To Stone Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Can't Get It Out Of My Head Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Evil Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Livin' Thing Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Ma-Ma-Ma Belle Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Mr. -

RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LSP 4600-4861

RCA Discography Part 15 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LSP 4600-4861 LSP 4600 LSP 4601 – Award Winners – Hank Snow [1971] Sunday Mornin' Comin' Down/I Threw Away The Rose/Ribbon Of Darkness/No One Will Ever Know/Just Bidin' My Time/Snowbird/The Sea Shores Of Old Mexico/Me And Bobby Mcgee/For The Good Times/Gypsy Feet LSP 4602 – Rockin’ – Guess Who [1972] Heartbroken Bopper/Get You Ribbons On/Smoke Big Factory/Arrivederci Girl/Guns, Guns, Guns/Running Bear/Back To The City/Your Nashville Sneakers/Herbert's A Loser/Hi, Rockers: Sea Of Love, Heaven Only Moved Once Yesterday, Don't You Want Me? LSP 4603 – Coat of Many Colors – Dolly Parton [1971] Coat Of Many Colors/Traveling Man/My Blue Tears/If I Lose My Mind/The Mystery Of The Mystery/She Never Met A Man (She Didn't Like)/Early Morning Breeze/The Way I See You/Here I Am/A Better Place To Live LSP 4604 – First 15 Years – Hank Locklin [1971]Please Help Me/Send Me the Pillow You Dream On/I Don’t Apologize/Release Me/Country Hall of Fame/Before the Next Teardrop Falls/Danny Boy/Flying South/Anna (With Nashville Brass)/Happy Journey LSP 4605 – Charlotte Fever – Kenny Price [1971] Charlotte Fever/You Can't Take It With You/Me And You And A Dog Named Boo/Ruby (Are You Mad At Your Man)/She Cried/Workin' Man Blues/Jody And The Kid/Destination Anywhere/For The Good Times/Super Sideman LSP 4606 – Have You Heard Dottie West – Dottie West [1971] You're The Other Half Of Me/Just One Time/Once You Were Mine/Put Your Hand -

The Oxford Companion to English Literature, 6Th Edition

B Bab Ballads, a collection of humorous ballads by W. S. lated by J. Harland in 1929 and most of his work is ^Gilbert (who was called 'Bab' as a child by his parents), available in English translation. first published in Fun, 1866-71. They appeared in Babylon, an old ballad, the plot of which is known 'to volume form as Bab Ballads (1869); More Bab Ballads all branches of the Scandinavian race', of three sisters, (1873); Fifty Bab Ballads (1877). to each of whom in turn an outlaw proposes the alternative of becoming a 'rank robber's wife' or death. Babbitt, a novel by S. *Lewis. The first two chose death and are killed by the outlaw. The third threatens the vengeance of her brother 'Baby BABBITT, Irving (1865-1933), American critic and Lon'. This is the outlaw himself, who thus discovers professor at Harvard, born in Ohio. He was, with Paul that he has unwittingly murdered his own sisters, and Elmer More (1864-1937), a leader of the New Hu thereupon takes his own life. The ballad is in *Child's manism, a philosophical and critical movement of the collection (1883-98). 1920s which fiercely criticized *Romanticism, stress ing the value of reason and restraint. His works include BACH, German family of musicians, of which Johann The New Laokoon (1910), Rousseau and Romanticism Sebastian (1685-1750) has become a central figure in (1919), and Democracy and Leadership (1924). T. S. British musical appreciation since a revival of interest *Eliot, who described himself as having once been a in the early 19th cent, led by Samuel Wesley (1766- disciple, grew to find Babbitt's concept of humanism 1837, son of C.