Model of High-Mountain Hiking Trails (Via Ferrata Type) in Tatra National Park – a Comparison Between Poland and Slovakia in the Context of the Alps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legislation for the Reuse of Biosolids on Agricultural Land in Europe: Overview

sustainability Review Legislation for the Reuse of Biosolids on Agricultural Land in Europe: Overview Maria Cristina Collivignarelli 1 , Alessandro Abbà 2, Andrea Frattarola 1, Marco Carnevale Miino 1 , Sergio Padovani 3, Ioannis Katsoyiannis 4,* and Vincenzo Torretta 5 1 Department of Civil and Architectural Engineering, University of Pavia, via Ferrata 1, 27100 Pavia, Italy; [email protected] (M.C.C.); [email protected] (A.F.); [email protected] (M.C.M.) 2 Department of Civil, Environmental, Architectural Engineering and Mathematics, University of Brescia, via Branze 43, 25123 Brescia, Italy; [email protected] 3 ARPA Lombardia, Pavia Department, via Nino Bixio 13, 27100 Pavia, Italy; [email protected] 4 Department of Chemistry, Laboratory of Chemical and Environmental Technology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece 5 Department of Theoretical and Applied Sciences, University of Insubria, via G.B. Vico 46, 21100 Varese, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 17 September 2019; Accepted: 25 October 2019; Published: 29 October 2019 Abstract: The issues concerning the management of sewage sludge produced in wastewater treatment plants are becoming more important in Europe due to: (i) the modification of sludge quality (biological and chemical sludge are often mixed with negative impacts on sludge management, especially for land application); (ii) the evolution of legislation (landfill disposal is banned in many European countries); and (iii) the technologies for energy and material recovery from sludge not being fully applied in all European Member States. Furthermore, Directive 2018/851/EC introduced the waste hierarchy that involved a new strategy with the prevention in waste production and the minimization of landfill disposal. -

Via Ferratas of the Italian Dolomites Volume 1

VIA FERRATAS OF THE ITALIAN DOLOMITES VOLUME 1 About the Author VIA FERRATAS OF James Rushforth is an experienced professional climber, mountaineer, skier and high-liner. His book The Dolomites: Rock Climbs and Via Ferrata was THE ITALIAN DOLOMITES nominated for the Banff Film Festival Book Award and was cited as ‘the best Dolomite guidebook ever produced’ (SA Mountain Magazine). James VOLUME 1 also works as a professional photographer and has won 12 international photography competitions and published work in numerous magazines by James Rushforth and papers including National Geographic, The Times and The Daily Telegraph. He has written tutorial and blog posts for a number of popular media platforms such as Viewbug and 500px, and appeared as a judge in several global competitions. Although based in the UK, James spends much of his time explor- ing the Italian Dolomites and is one of the leading authorities on the region – particularly with regards to photography and extreme sports. He is part of the Norrøna Pro Team and is kindly supported by Breakthrough Photography, Landcruising and Hilleberg. James can be contacted at www.jamesrushforth.com. Other Cicerone guides by the author Ski Touring and Snowshoeing in the Dolomites JUNIPER HOUSE, MURLEY MOSS, OXENHOLME ROAD, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA9 7RL www.cicerone.co.uk © James Rushforth 2018 CONTENTS First edition 2018 ISBN: 978 1 85284 846 0 Map key ...................................................... 9 Overview map ................................................ 10 This guide further develops and replaces the previous guide by Graham Fletcher Route summary table ........................................... 12 and John Smith with the same title published under ISBNs 9781852843625 and Foreword .................................................... 17 9781852845926 in 2002 and 2009 respectively. -

Exploring Slovenia's Julian Alps and Beyond

Exploring Slovenia’s Julian Alps and Beyond Two Treks and Balkan Culture in an Undiscovered Corner of the Alps August 30, 2021 – September 13, 2021 – Trip #2167 Triglav National Park Overview Join us for a wonderful fifteen-day trip to the undiscovered hiking and scenic paradise of Slovenia. We will pass medieval castles, churches, and traditional mountain villages as we walk through valleys, across mountain pastures, and traverse mountain ridges with towering peaks all around us. This trip combines two rugged short treks (one carrying all our gear and staying in mountain huts, and the other staying in hotels with luggage transport), an exciting ascent to Slovenia’s highest peak, and visits to the most scenic and interesting regions of this small, but incredibly beautiful country. A few words about Slovenia itself: it is a small country located in southern central Europe at the intersection of major trade routes and of the Slavic, Germanic, and Romance languages and cultures. Historically part of many empires including Rome, Austro-Hungarian, Venice, and France, it is currently a prosperous, democratic European country of two million persons. Over 50% of its landmass remains forested. It is exceptionally bio-diverse for its size particularly as pertains to endemic cave species. Slovenia’s Place in Europe Trip Difficulty This trip is rated strenuous #6. Trip Rating System. Excluding breaks we will hike from five to seven hours per day, between 6 and 14 miles, with an average elevation gain of about 2500 feet. The terrain is rugged and steep in places, and requires agility. There will be sections on narrow trails with exposure (steep drop-offs). -

Via Ferrata: a Short Introduction Giuliano Bressan, Claudio Melchiorri CAI – Club Alpino Italiano

Via Ferrata: A short introduction Giuliano Bressan, Claudio Melchiorri CAI – Club Alpino Italiano 1. Introduction In the last years, the number of persons climbing “vie ferrate” has rapidly increased, and this manner of approaching mountains is becoming more and more popular among mountaineers and hikers, in particular among young persons. The terms “via ferrata” and “sentiero attrezzato” (or equipped path) indicate that a set of fixed equipment (metallic ropes, ladders, chains, bridges, …) is installed along an itinerary in order to facilitate its ascension, guaranteeing at the same time a good margin of security. In this manner, also non extremely expert persons may have the opportunity to approach mountains and vertical walls that would be climbable, without this equipment, only by means of standard climbing techniques and equipment (i.e. rope, pitons, and so on). With this fixed equipment it is then possible to grant almost to everybody the emotion of altitudes and the excitement of vertical walls, without taking major risks and without being involved, possibly, in dangerous situations. Nevertheless, practicing “vie ferrate” should not be compared with the classical climbing activity. As a matter of fact, also considering the physical and psychological engagement necessary in any case to climb a “via ferrata” (some are very difficult from a technical and physical point of view), very different are the technical skills, the experience, the capabilities and the emotional control needed to face in a proper way any negative situation possibly occurring in a mountaineering activity. Nowadays, the term “via ferrata” has been internationally adopted, although in some countries they are also known as Klettersteig (this word indicates the specific karabiners to be used in this activity). -

Tourism Development and Promotion Project Overview of Awarded Grants

This project is funded by the European Union Tourism Development and Promotion Project rd Overview of Awarded Grants – 3 Call for Proposals No Grant recipient Name of the Area of intervention RCC Grant Economies (Headquarters) action value in € covered by the action 1 Nucleus Albania Youth travel - Adventure tourism – Hiking and gastro tourism 53,950.50 AL, MK (Tirana) Walking through beauty and Establishment and promotion of anew cross-border hiking trail between culture Albania and North Macedonia in the Ohrid lake area encompassing gastro, religious, rural and ecological tourism attractions. Goal: Including some 100 women and youth run MSMEs in tourism industry. 2 Mountaineering Amazing Velež Adventure tourism – Via Dinarica (hiking and climbing) 52,938.00 BA Association Treskavica Development of 25 new kilometres of Via Dinarica hiking trail in Velež (Sarajevo) Mountian including via ferrata, planning and marking ten new alpine routes, training of 15 alpine and mountaniering guides, and promotion of new adventure tourism products through mountaniering maps. Goal: Improving quality of services and infrastructure along Via Dinarica. 3 Digital Future Promoting the Adventure tourism – Gastronomy 48,000.00 AL, (Tirana) Balkan Kosovo*, traditional Establishment of a network of gastro-tourism partners (restaurants, hotels, MK cuisine through tour operators) in three economies, development of a mobile app serving the use of digital as a gastro-tourism guide, and promotion of the app and regional gastro- means tourism offer through digital marketing campaign, as well as promotional videos and print products. Goal: Promoting local gastro-tourism businesses and improving customer experience. Fra Anđela Zvizdovića 1, UNITIC Tower B/6, 71000 Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina Tel. -

PDF Download the Dolomites: Rock Climbs and Via Ferrata Ebook Free

THE DOLOMITES: ROCK CLIMBS AND VIA FERRATA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James Rushforth | 500 pages | 21 Aug 2014 | Rockfax Ltd | 9781873341971 | English | Sheffield, United Kingdom The Dolomites: Rock Climbs and via Ferrata PDF Book UKC Advertising. World War II interrupted these endeavors, but not for long. If you have a short time one day and your period is not in summer this proposal is for you! On the descent, we usually spend the night in the Torrani Hut, which is located about 20 mins below the summit. The route follows largely the North Ridge of the mountain and is one of the longest in the Dolomites. Rated very difficult and very long! The Sporthotel Europe had me booked along with the other 4 clients, even though I was only paying for guiding as I had my own apartment nearby. Perfect program for a bad weather or easier day in between the long high peaks via ferrata days! Erfahren Sie mehr. Exceptionally long two day routes such as those found on the Marmolada South face have been spread over four pages to give the best information possible. Drive to Passo Giau. A really helpful addition is the addition of colour coded pitch grades on topos. Check our Dolomites via ferrata itinerary options! Help me improve the website by measuring any errors that occur. Menu Skip to left header navigation Skip to right header navigation Skip to main content Skip to primary sidebar Skip to footer. I had taken a gym class in high school that involved a few weeks of rock climbing, albeit the indoor gym kind, but I remembered a key to rock climbing is to push with your legs, not pull with your hands, which was helpful to apply. -

Njihuni Me Via Ferratat E Kosovës

Via Ferrata është një shteg i cili ndërtohet në pjesët shkëmbore por që është e mundur të shfrytëzohet nga çdo vizitor i cili kërkon aktivitete që krijojnë adrenalinë dhe aventurë. Kryesisht ndërtohet duke e vendosur një fije metalike e cila kalon përgjatë gjithë shtegut shkëmbor si dhe vendosja e shkallëve të hekurta të cilat të mundësojnë që të arrini lartësinë pa ndonjë problem, dhe duke i përdorur pajisjet e nevojshme të sigurisë gjatë ngjitjes tuaj do të përjetoni një kënaqësi të paharruar në eksperiencën tuaj jetësore. ndonjë problem, dhe duke i përdorur Kosova është destinacioni numër një dhe Zipline në Pejë, vizita në objekte pajisjet e nevojshme të sigurisë gjatë i Via Ferratave në rajonin tonë. Këtu të trashëgimisë kulturore dhe historike ngjitjes tuaj do të përjetoni një kënaqësi gjenden shtatë të tilla ku adhuruesit e në Prizren, apo mbetjet arkeologjike të paharruar në eksperiencën tuaj alpinizmit dhe aktiviteteve në natyrë të periudhës bizantine dhe mure të jetësore. mund të ngjiten dhe të përjetojnë kështjellave të lashta. adrenalinën. NJIHUNI ME VIA FERRATAT E KOSOVËS Via Ferrata është një shteg i cili ndërtohet Secila prej shtatë Via Ferratave të në pjesët shkëmbore por që është e Pejë - Via Ferrata "Ari" Kosovës është unike. Ato dallojnë mundur të shfrytëzohet nga çdo vizitor i për nga shkalla e vështirësisë, cili kërkon aktivitete që krijojnë adrenalinë Via Ferrata e parë e ndërtuar në Kosovë natyra ku janë ndërtuar, peisazhet që dhe aventurë. Kryesisht ndërtohet duke është e quajtura “Via Ferrata Ari”, që shpalosen kur ngjitesh deri lart dhe e vendosur një fije metalike e cila kalon u funksionalizua në periudhën 2013- nga mundësitë e ndryshme që ofrojnë përgjatë gjithë shtegut shkëmbor si dhe 2014. -

The Iron Way

ITALY THE IRON WAY The First World War saw many devastating battles take place across Europe, with the Italian Dolomites being one of the lesser-known settings. Justine Gosling follows in the footsteps of thousands of soldiers as she tackles a few classic via ferrata routes… 56 M A R | A P R 2 0 1 8 www.wiredforadventure.com ITALY www.wiredforadventure.com M A R | A P R 2 0 1 8 57 ITALY who’s writing? Around her ‘proper’ job working in a central London hospital and volunteering her skills in international humanitarian disaster zones, JUSTINE GOSLING plans and undertakes her own unsupported ENJOYING RUGGED 360 DEGREE VIEWS multi week expeditions that tries to engage people in history, often in the Arctic. was devouring the cheese roll held in my right hand as I stared out at the dark UK POLAND clouds gathering above the mountain GERMANY peak. We’d make this lunch stop a short CZECH REP. one, keen to get to the next hut before the storm arrived. Curious, my left hand I AUSTRIA scoured the ground next to where I was SWITZERLAND sat. It was littered with tiny scraps of rusting metal and nails, FRANCE resting between the pretty yellow fl owers and stones. Th ere DOLOMITES I saw it. A small, metallic, imperfectly moulded sphere. It stood out because of its shape and lack of corrosion. Once I ITALY picked it up and felt the weight of the small piece of lead, I knew that it was a bullet. Almost without a doubt fi red over 100 years ago in the appropriated, and expanded the routes. -

Via Ferrata Dolomites Safety

! ! ! Via Ferratas A introduction to the “art of climbing the Via Ferratas in the Dolomites.” A Short history of the ferratas It’s hard to believe that just 90 or so years ago, during World War I, our mountains were wracked by violence: explosions blew of summits and shrapnel pierced tree trunks. Even now, the ground is littered in places with bits of barbed wire and other debris from the conflict. The history of the Via Ferrata in the Dolomites starts with this war. The “Alpini” )Italian mountain troops( and the “Kaiserjaegers” )Austrian mountain troops( each sought supremacy in the Dolomites region, and some of the high passes were intense battlegrounds. During the First World War, via ferrata were constructed in the Italian Dolomites so that troops could move equipment and artillery from one side of the mountain to the other. After the war, the army abandoned the routes and local people took to maintaining them, recognizing their potential for attracting visitors to the area. _____________________________________________________________________________________________ "Dolomites mountains are a natural site on UNESCO's World Heritage List!" 1 ! ! ! The Dolomites via ferrata routes are accessible to most people, not just technical climbers. Hikers and scramblers with reasonable fitness and a head for heights can also enjoy the routes with a mountain guide and the right gear and training. Clothing: You need only normal hiking clothes suitable for alpine areas. )read our INFO 5 pdf file(. Equipment: On guided days, I will supply you with all the necessary gear for via ferrata: • Helmet and Harness • Ferrata gloves, lanyards + shock absorber • Crampons and ice axe or trekking sticks )only if are necessary( If you are a beginner, you and me will climb an easy via ferrata on the first guided day. -

Via Ferrata, I Have Translated Instances of Klettersteig with the Abbreviation VF/KS Throughout

RECOMMENDATION FOR THE CONSTRUCTION OF KLETTERSTEIGS (ALSO KNOWN AS VIA FERRATE) AND WIRE CABLE BELAY SYSTEMS Produced by the German Alpine Club and the Austrian Board of Mountain Safety Editors: Chris Semmel und Florian Hellberg, German Alpine Club Safety Analysis Unit Munich, Germany, 2008 © 2008 Translated from the German by Dave Custer, American Alpine Club Delegate to the UIAA Safety Commission © 2009 Contents Translator’s notes.......................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction................................................................................................................................... 3 1 Planning a VF/KS....................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Basic considerations................................................................................................................ 4 1.1.1 Definition of terms............................................................................................................... 4 1.1.2 Preparation for VF/KS construction................................................................................. 4 1.2 Mountain sport aspects.......................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Permission/permits................................................................................................................. 6 1.4 Legal considerations….......................................................................................................... -

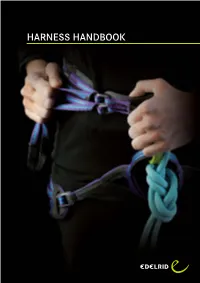

HARNESS HANDBOOK INTRO Your Climbing Harness Is the Central Link in the Safety Chain

HARNESS HANDBOOK INTRO Your climbing harness is the central link in the safety chain. Whether you’re climbing multi-pitch alpine routes, cranking your way up sport routes or training at your local climbing wall, you need a har - ness you can rely on. There are numerous different types of harness on the market. They all have their pro and cons, and are all intended for different types of climbing. We’ve put this handbook tog- ether to share our expertise and provide an over - view of the most important harness types and their materials and construction. It also offers advice on which harness to choose and how to use and look after your harness. At EDELRID, we’re constantly working to improve our harnesses to meet the demands of modern climbers. This handbook also provides a glimpse behind the scenes to give you an insight into how we design, manufacture and test our harnesses. Made by climbers for climbers. The EDELRID team is made up of passionate climbers and alpinists. In addition, we work closely with professional clim- bers and mountain guides. We understand the demands that climbers place on their equipment. CREATIVE TECHNOLOGY is our credo – and we apply it to our innovative harnesses to make versa- tile products that meet and exceed the highest quality standards. We have over 150 years of expe- rience in mountain sports. This combination of experience and enthusiasm constantly drives us to explore new paths and only accept maximum per- formance. And, as a mountain sports company, we naturally make quality management and sustaina- bility our highest priorities. -

The Impact of in North Macedonia Rock Climbing

CASE STUDY The Impact of Rock Climbing in North Macedonia THE IMPACT OF ROCK CLIMBING IN NORTH MACEDONIA August 2020 1 THE CLIMBING INITIATIVE ABOUT THE CLIMBING INITIATIVE The Climbing Initiative is a Colorado-based nonprofit supporting climbing communities worldwide. Through research, community engagement, and partnerships, we bring together organizations invested in the future of climbing and develop best practices for supporting the growth of climbing in emerging contexts. We believe rock climbing can empower individuals, create new sources of livelihood, and foster the development of a more sustainable and equitable world. climbinginitiative.org Cover photo by Goran Kuzmanovski Natalija Ristevska climbing the Krali Marko highball boulder in Prilep Design by Mario Minchevski behance.net/mDesign | @mario.minchevski Photographers Goran Kuzmanovski | @goran.kuzeto Keti Talevska | @keti_talevska Cosima Vom Meer | @cosivmeer Veronica Baker | @vero.baker Copyright © 2020 The Climbing2 Initiative. All rights reserved. CASE STUDY The Impact of Rock Climbing in North Macedonia CONTENTS 1 Summary 2 Introduction 4 History 9 Economic Impact 13 Social Impact 15 Enviromental Impact 18 Challenges & Opportunities 23 Recommendations 25 Conclusions 3 THE CLIMBING INITIATIVE 4 Biljana Talevska climbing in Demir Kapija Photo by Goran Kuzmanovski CASE STUDY The Impact of Rock Climbing in North Macedonia SUMMARY North Macedonia counts approximately 1,300 sport climbing and bouldering routes, but locals estimate that 90 percent of the country’s climbing areas remain undiscovered. Although the country carries a strong tradition of mountaineering, climbing is still in an early stage of development, marked by little public understanding of the sport. The Macedonian government is enthusiastic about promoting outdoor tourism.