Complete Retrieved Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

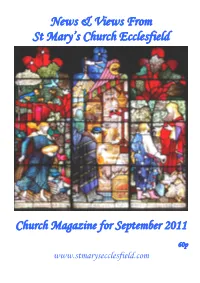

Front Cover- the Lower Left 3 Panels of the Parables of Nature (Gatty) Window 2

News & Views From St Mary’s Church Ecclesfield Church Magazine for September 2011 60p www.stmarysecclesfield.com First Words… Back To School – September is the “back to school” month. It’s also the month when lots of things get going again in the life of the Church. The changes that were outlined in last month’s magazine start to take shape in September. During this month we’ll start to think about the shape of our Joint Service. We’ll also start to plan our new After School Club. Harvest – This year we celebrate Harvest on 25th September with a Joint Service of Parish Communion at 10.30 a.m. Please come along and join with us. Celebration Weekend – A date for your diary. The weekend of 8/ 9 October will be a time of great celebration here in Ecclesfield. We will be celebrating the 700th anniversary of the first named Vicar of Ecclesfield and the 400th anniversary of the King James Version of the Bible. Keep a look out in later magazines for further information. Daniel Hartley The Collect for Harvest Sunday Eternal God, you crown the year with your goodness and you give us the fruits of the earth in their season: grant that we may use them to your glory, for the relief of those in need and for our own well-being; through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord, who is alive and reigns with you, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen Front cover- The Lower Left 3 Panels of the Parables of Nature (Gatty) window 2 The Gatty Memorial Hall Priory Road Ecclesfield Sheffield S35 9XY Phone: 0114 246 3993 Accommodation now available for booking GROUPS • MEETINGS • ACTIVITIES FUNCTIONS Ecclesfield Church Playgroup The Gatty Memorial Hall Priory Road Ecclesfield A traditional playgroup for children 2½ to 5 years. -

Anthony E. Santelli II

Journal of Markets & Morality Volume 14, Number 2 (Fall 2011): 541–549 Copyright © 2011 Anthony E. Santelli II “Nine Libertarian Heresies”— A Surresponse Anthony E. Santelli II Finn says that my arguments fail to erect a position that is both Catholic and libertarian. I disagree and will expound on them here further, showing how jus- tice for all is possible within such an order. In addition, I will show that Finn’s belief in the redistribution of income is contrary to Catholic social thought. It is he who fails to erect a position that is both Catholic and liberal. Finn is misguided in focusing on a “one-time grand redistribution of wealth after which no further redistributions would be allowed” (a proposal I describe briefly in a footnote) as being an essential part of my position. The core of my thesis is the Christian methodology of doing political economy that I explained. This methodology says that any law, tax, right, rule, regulation, or cultural imperative that provides an incentive to act contrary to the nature of God or a disincentive to act in accord with the nature of God is, by its nature, contrary to God’s Order (capital O) and, as such, can be judged to be wrong and, hence, should be changed or abolished. God is all Good, Beauty, Truth, and One. Therefore any tax on or regulation of goodness, beauty, truth, or unity inhibits or provides a disincentive against humans acting like God and so cannot be a part of a just social order. I take the position that this is the only valid methodology by which a Christian can do political economy, that is, by which a Christian can seek to develop a just social order. -

The Social Doctrine of the Church Today

“Instaurare omnia in Christo” The Social Doctrine of the Church Today Christ, the King of the Economy Archbishop Lefebvre and Money Interview With Traditional Catholic Businessmen July - August 2016 It is not surprising that the Cross no longer triumphs, because sacrifice no longer triumphs. It is not surprising that men no longer think of anything but raising their standard of living, that they seek only money, riches, pleasures, comfort, and the easy ways of this world. They have lost the sense of sacrifice” (Archbishop Lefebvre, Jubilee Sermon, Nov. 1979). Milan — fresco from San Marco church, Jesus’ teaching on the duty to render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s; and to God, the things that are God’s. Letter from the Publisher Dear readers, Because he is body and soul, man has basic human needs, like food, drink, clothes, and shelter, which he cannot obtain unless he has basic, minimal possessions. The trouble is that possessions quickly engender love for them; love breeds dependence; and depen- dence is only one step away from slavery. Merely human wisdom, like Virgil’s Aeneid, has stigmatized it as “the sacrilegious hunger for gold.” For the Catholic, the problem of material possessions is compounded with the issue of using the goods as if not using them, of living in the world without being of the world. This is the paradox best defined by Our Lord in the first beatitude: “Blessed be the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.” Our civilization is fast heading towards decomposition partly for not understanding these basic truths. -

Development of Catholic Moral Doctrine: Probing the Subtext M

Boston College Law School Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Law School Faculty Papers January 2003 Development of Catholic Moral Doctrine: Probing the Subtext M. Cathleen Kaveny Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/lsfp Part of the Ethics in Religion Commons, History of Christianity Commons, and the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation M. Cathleen Kaveny. "Development of Catholic Moral Doctrine: Probing the Subtext." University of St. Thomas Law Journal 1, no.1 (2003): 234-252. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law School Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE DEVELOPMENT OF CATHOLIC MORAL DOCTRINE: PROBING THE SUBTEXT M. CATHLEEN KAVENY* I. INTRODUCTION Judge Noonan has been speaking and writing explicitly about the gen- eral topic of development of doctrine in Catholic moral theology for ap- proximately a decade now. In 1993, he published a now-classic article on the topic in Theological Studies, arguably the most prominent journal of Catholic theology in the United States.' He gave a plenary address on de- velopment of moral doctrine to the annual meeting of the Catholic Theolog- ical Society of America in 1999.2 Judge Noonan developed his arguments and analyses more extensively in the fall of 2003, when he delivered a se- ries of eight Erasmus Lectures at the University of Notre Dame on the de- velopment of moral doctrine. -

TRANSFORMING PRESENCE What Does It Mean To

GETTING THERE Chelmsford Cathedral is in the city centre, just a few minutes walk from Chelmsford railway station. St John’s Stratford is on The Broadway, Stratford E15 1NG TRANSFORMING PRESENCE and only a five minute walk from Stratford railway station. St John’s Colchester is in St John’s Close, Colchester, Essex What does it mean to me? CO4 0HP. LENT LECTURES 2016 www.transformingpresence.org.uk LECTURES Week One with Stephen Cottrell, Bishop of Chelmsford LENT 2016 Living distinctively - What does it mean to be a disciple today? 23 Feb in the Cathedral; 24 Feb in St John’s, Colchester; Lent is a time when it is good for Christian people to 25 Feb in St John’s, Stratford. re-set the compass of their discipleship so as to be ready to celebrate the Easter feast. Week Two with Peter Hill, Bishop of Barking Evangelising effectively - How can I share and bear witness to my faith? One of the things to come out of the Time to Talk discussions 1 March in the Cathedral; 2 March in St John’s, Colchester; in April 2015 was a desire for more teaching about prayer 3 March in St John’s, Stratford. and discipleship. Week Three with Roger Morris, Bishop of Colchester In Lent 2016 the bishops of the diocese, with help from one Serving Accountably - To whom do I render my life? or two other members of the Bishop’s Staff and Cathedral 8 March in the Cathedral; 9 March in St John’s, Colchester; team, will present four Lectures on the four themes of 10 March in St John’s, Stratford. -

Course Descriptions and Readings

International Theological Institute COURSE DESCRIPTIONS AND READINGS STM / LA YEAR 1, SEMESTER 1 STM/LA 111: AN INTRODUCTION TO LIBERAL EDUCATION, WRITING AND RHETORIC (3 ECTS) The focus of this course is to introduce our students to the contemplative heart of liberal education— the truth and beauty of our intellectual life which must always be pursued for its own sake—and secondarily to impart the practical skills of writing and rhetoric that will foster and bring to maturity such a life. Sources: C.S. Lewis, ‘Learning in Wartime’; Jean Leclercq OSB, The Love of Learning and the Desire for God (chaps. 1 and 7); Pope Benedict XVI, ‘Address at the College de Bernardins’. Bl. John Henry Newman, Idea of a University (excerpts); Christopher Dawson, The Crisis of Western Education. A. G. Sertillanges, The Intellectual Life; Marcus Berquist et al., A Proposal for the Fulfilment of Catholic Liberal Education; M. Adler and Van Doren, How to Read a Book; Sister Miriam Joseph, C.S.C., The Trivium: the Liberal Arts of Logic, Grammar and Rhetoric; Scott Crider, The Office of Assertion. J. Guitton, Student’s Guide to the Intellectual Life. Dorothy Sayers, ‘The Lost Tools of Learning’. STM/LA 112: INTRODUCTION TO PHILOSOPHY: EARLY PLATONIC DIALOGUES (6 ECTS) The presocratic movement develops in Plato into a science of philosophy. This science is called ‘dialectics’ and refers to the understanding of the eternal ideas. The chosen dialogues are located at the beginning of the curriculum and consider principles of Plato’s thought. In Socrates they reveal the exemplary way of a philosopher as a lover of wisdom, who dedicates his life to the discernment of an unchangeable truth in service of the gods and the polis: “The unexamined life is not worth living for men” (Apology 38a). -

How to Read, Study and Benefit from Papal Encyclicals

How to Read, Study and Benefit from Papal Encyclicals Contents What is an Encyclical ..................................................................................................................................... 1 How to Read and Study an Encyclical ........................................................................................................... 2 Are Encyclicals Infallible Teachings of a Pope ............................................................................................... 2 History of Encyclicals ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Why Read Encyclicals if You are Not Catholic? ............................................................................................. 4 Links to Other Encyclicals and Lists of All Encyclicals ................................................................................... 4 List of Encyclicals ........................................................................................................................................... 4 What is an Encyclical The word encyclical literally means "in a circle." It is a letter intended to travel— to circulate. However in modern times it has become almost exclusively used to denote teachings from the Pope. Comparing an encyclical to other kinds of official Roman Catholic documents is a good way to understand the significance of an encyclical. Firstly, when the pope makes a declaration of some article of faith or moral law it is -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/29/2021 04:24:58AM Via Free Access

journal of jesuit studies 5 (2018) 610-630 brill.com/jjs Moral Economy and the Jesuits Paola Vismara (†)* University of Milan Abstract In this article, originally published in French under the title “Les jésuites et la morale économique” (Dix-septième siècle 237, no. 4 [2007]: 739–54), Paola Vismara presents the Jesuits’ major contributions to the teaching of moral economy from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century. In particular, Vismara explores Jesuit doctrines on moral economy and focuses on various Jesuit approaches to the problems of contracts and the management of capital, with particular attention paid to lending at interest. Retracing the most significant early modern Jesuit theologians’ contributions to issues of moral economy, including the treatise of Leonard Lessius, Vismara paints a complex picture, highlighting the new ideas contained in the works of the Jesuit theologians, shedding light on disputes between probabilist and rigorist theologians, and discuss- ing the Roman Church’s responses to various theological orientations to moral econo- my over three centuries. Keywords Jesuits – Society of Jesus – usury – interest – extrinsic titles – vix pervenit – moral theology – triple contract – probabilism – rigorism Moral Economy within the Society of Jesus: An Introduction Early modern Jesuit doctrinal and theoretical reflections concerning matters of moral theology have always been the object of much attention because of their intellectual importance during the period, and because of the con- troversies they engendered. These reflections and their pastoral implications * The copyright of the original article in French is with the publisher Humensis, whom we thank for granting us permission to publish its English translation. © Paola vismara, 2018 | doi:10.1163/22141332-00504007 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the prevailing cc-by-nc license at the time of publication. -

De-Coding Mammon : Money in Need of Redemption

1 DE-CODING MAMMON : MONEY IN NEED OF REDEMPTION Submitted by Peter John Dominy to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology November 2010 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other university. SIGNED...................................................................................... 2 Abstract This thesis is an attempt to understand the suspicion of money implied in Jesus' statement that it is impossible to serve both God and Mammon. I argue on the basis of Scripture, reason and tradition that problems associated with money do not arise simply from the way it is used, but from the nature of money itself. This is argued in three sections. First I consider the history of money and in particular of the commodity theory of money. Second I consider the issues of debt and interest, of central concern in the Christian Scriptures. Finally I consider money through four different lenses: justice, value, desire and power. The argument as a whole leads up to the last of these. As was already suggested by Jacques Ellul fifty years ago, I argue that money must be understood as a cosmic power to which we are all subject and which is in need of redemption. In the second and third sections I make suggestions as to what the redemption of money might look like. -

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY of AMERICA a Program for a Christian Social Order: the Organic Democracy of René De La Tour Du Pin A

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA A Program for a Christian Social Order: The Organic Democracy of René de La Tour du Pin A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Joseph F.X. Sladky Washington, D.C. 2012 A Program for a Christian Social Order: The Organic Democracy of René de La Tour du Pin Joseph F.X. Sladky, Ph.D. Director: Rev. Jacques M. Gres-Gayer, Th.Dr., Hist.Dr. René de La Tour du Pin was one of the leading social Catholic theorists during the latter half of the nineteenth century. This dissertation examines La Tour du Pin’s role in attempting to lay the foundations for a more just and representative Christian social order. There is a particular focus on the analysis of his social theories and the examination of the utility and foresight of his many contributions to Catholic social thought. La Tour du Pin was at the helm of Association catholique, the most influential social Catholic journal in late nineteenth century Europe. He was also the secretary and moving spirit behind the Fribourg Union, a multi-national group of prominent and influential social Catholics, whose expertise was drawn upon by Pope Leo XIII in the drafting of Rerum Novarum. Later, some of his ideas found their way into Quadragesimo anno. Through his corporative system he promoted a program which organized society by social function and which gave corporations public legal recognition and autonomy in all areas pertaining to their proper sphere. -

Faith Leaders' Open Letter to the Prime Minister

http://interfaithrefugeeinitiative.org/ We are leaders from Britain’s major faiths: Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, Jain, Jewish, Muslim, Sikh, Zoroastrian. All our faiths compel us to affirm the dignity of all human beings and to offer help to anyone in need. As people of faith, we call on your Government urgently to revise its policy towards refugees. The best of this country is represented by the generosity, kindness, solidarity and decency that Britain has at many times shown those fleeing persecution, even at times of far greater deprivation and difficulty than the present day. We rejoice in the mosaic of different faiths and British communities that we now represent. We are proud that in May 2016, in a survey by Amnesty International, 83% of Britons said they would welcome refugees into their neighbourhoods and households. In the face of the unfolding human catastrophe, there are immediate and viable steps that the Government can take to offer sanctuary to more refugees. We call on you to create safe, legal routes of travel, for example by adopting fair and humane family reunion policies for refugees. Under the present immigration rules, a British doctor of Syrian origin could not bring her parents from a refugee camp in Lebanon – even though they were refugees and she could support and house them. A Syrian child who arrived alone in the UK could not bring his parents from a refugee camp in Jordan – even if the child were recognised a refugee and even though his parents were themselves refugees. Families in these situations can currently be reunited only by resorting to desperately unsafe irregular journeys, sometimes ending in avoidable tragedies. -

ANNUAL BRIEFING for PARISHES Financial Year 2011 the Church of England at Work in Essex and East London

ANNUAL BRIEFING FOR PARISHES Financial year 2011 The Church of England at work in Essex and East London We are all in this together: thank you for all you do The active participation of our churches in every fresh approach to daily Bible-reading. Many people followed his Lent course, A Rich community makes the Diocese of Chelmsford a Inheritance.The Bishop’s Lent Appeal for missionary presence that helps to sustain the life of Kenya was generously supported and raised Essex and East London. more than £36,000 (see Revving up for the Bishop’s Lent Appeal on page 3). International Completing his first year in office the new Some 21 men and women were ordained as partnerships were strengthened with Bishop of Chelmsford, Rt Revd Stephen deacons and 24 as priests in 2011. Learning exchange visits to Kenya and Sweden. Cottrell, introduced Transforming Presence – and development opportunities were The Diocese led the national celebrations of Strategic Priorities for the Diocese of provided to lay and ordained leaders of the 400th anniversary of the King James Chelmsford at Diocesan Synod, the regional church communities including children’s and Version of the Bible taking an innovative ‘parliament’ of the Church of England, in young people’s groups. approach (see Diocese raises a glass to year November 2011.The strategic principles of of the Bible on page 2). Chelmsford was a top Transforming Presence won enthusiastic The Diocesan Board of Education agreed to diocese for participation in Back to Church support. See A blueprint for change on page 3. five church schools becoming academies and set up an umbrella trust for new academies.