Very Important Poultry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Confounding Castle Pages 27-28

As you enter the next room, you hear a rustling in the dark, followed by a hiss. Four eyes peer out of the shadows, watching you. You stand perfectly still, making sure not to move, as a creature steps out into the light and looks you over. At first, it just seems like an odd looking, out of place chicken – perhaps a little bit bigger than other chickens you might have seen, but other than that, just a regular bird. But something about it seems off, and after a moment, you realize what it is – this bird doesn’t have a tail. Then, you realize that you’re wrong. It does have a tail, but its tail is a living snake, a second pair of eyes that stare at you. “What are you doing in my larder?” the creature squawks at you. You explain that you’re just trying to find your way to the Griffin’s tower, and it calms down considerably. “Oh, okay then. I don’t like people poking around in here, but if you’re just passing through it’s no problem. The ladder up into the Clock tower is right over there.” You are ready to leave, but curiosity overtakes you, and you ask the creature what it is. “I shall answer your question,” it hisses, “with a song.” Then, it throws back its bird head and begins to crow. I am the mighty cockatrice I like to eat up grains of rice But I also enjoy munching mice I do not like the cold or ice I’ve said it once and I will say it thrice I am the Cockactrice! I am the Cockatrice! “Myself, along with the Griffin, the Dragon, and a few others, all came to live here with the Wizard. -

Ing Items Have Been Registered

ACCEPTANCES Page 1 of 27 August 2017 LoAR THE FOLLOWING ITEMS HAVE BEEN REGISTERED: ÆTHELMEARC Ceara Cháomhanach. Device. Purpure, a triquetra Or between three natural tiger’s heads cabossed argent marked sable. There is a step from period practice for the use of natural tiger’s heads. Serena Milani. Name change from Eydís Vígdísardóttir (see RETURNS for device). The submitter’s previous name, Eydís Vígdísardóttir, is retained as an alternate name. Valgerðr inn rosti. Device. Argent, three sheep passant to sinister sable, each charged with an Elder Futhark fehu rune argent, a bordure gules. AN TIR Ailionóra inghean Tighearnaigh. Device change. Argent, a polypus per pale gules and sable within a bordure embattled per pale sable and gules. The submitter’s previous device, Argent, on a bend engrailed azure between a brown horse rampant and a tree eradicated proper three gouttes argent, is retained as a badge. Aline de Seez. Badge. (Fieldless) A hedgehog rampant azure maintaining an arrow inverted Or flighted sable. Nice badge! Alrikr Ivarsson. Name (see RETURNS for device). The submitter requested authenticity for an unspecified language or culture. Both name elements are in the same language, Old East Norse, but we cannot say for sure whether they are close enough in time to be authentic for a specific era. Anna Gheleyns. Badge (see RETURNS for device). Or, a rabbit rampant sable within a chaplet of ivy vert. Annaliese von Himmelreich. Name and device. Gules, a nautilus shell argent and on a chief Or three crows regardant sable. Annora of River Haven. Name. River Haven is the registered name of an SCA branch. -

Characterisation of the Cattle, Buffalo and Chicken Populations in the Northern Vietnamese Province of Ha Giang Cécile Berthouly

Characterisation of the cattle, buffalo and chicken populations in the northern Vietnamese province of Ha Giang Cécile Berthouly To cite this version: Cécile Berthouly. Characterisation of the cattle, buffalo and chicken populations in the northern Vietnamese province of Ha Giang. Life Sciences [q-bio]. AgroParisTech, 2008. English. NNT : 2008AGPT0031. pastel-00003992 HAL Id: pastel-00003992 https://pastel.archives-ouvertes.fr/pastel-00003992 Submitted on 16 Jun 2009 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Agriculture, UFR Génétique, UMR 1236 Génétique Alimentation, Biologie, Biodiva project UR 22 Faune Sauvage Elevage et Reproduction et Diversité Animales Environnement, Santé Thesis to obtain the degree DOCTEUR D’AGROPARISTECH Field: Animal Genetics presented and defended by Cécile BERTHOULY on May 23rd, 2008 Characterisation of the cattle, buffalo and chicken populations in the Northern Vietnamese province of Ha Giang Supervisors: Jean-Charles MAILLARD and Etienne VERRIER Committee Steffen WEIGEND Senior scientist, Federal Agricultural -

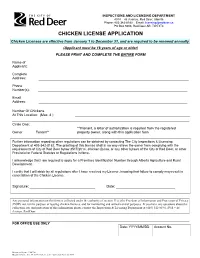

Chicken License Application Form for 2014

INSPECTIONS AND LICENSING DEPARTMENT 4914 – 48 Avenue, Red Deer, Alberta Phone: 403-342-8182 Email: [email protected] PO Box 5008, Red Deer AB T4N 3T4 CHICKEN LICENSE APPLICATION Chicken Licenses are effective from January 1 to December 31, and are required to be renewed annually (Applicant must be 18 years of age or older) PLEASE PRINT AND COMPLETE THE ENTIRE FORM Name of Applicant: Complete Address: Phone Number(s): Email Address: Number Of Chickens At This Location: (Max. 4 ) Circle One: **if tenant, a letter of authorization is required from the registered Owner Tenant** property owner, along with this application form Further information regarding other regulations can be obtained by contacting The City Inspections & Licensing Department at 403-342-8182. The granting of this license shall in no way relieve the owner from complying with the requirements of City of Red Deer bylaw 3517/2014, Chicken Bylaw, or any other bylaws of the City of Red Deer, or other Provincial or Federal Statutes or Regulations in force. I acknowledge that I am required to apply for a Premises Identification Number through Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development. I certify that I will abide by all regulations after I have received my License, knowing that failure to comply may result in cancellation of the Chicken License. Signature: ______________________________ Date: ___________________________ Any personal information on this form is collected under the authority of section 33 (c) the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy (FOIP) Act for the purpose of issuing chicken licenses, and for monitoring and animal control purposes. If you have any questions about the collection, use and protection of this information please contact the Inspections & Licensing Department at (403) 342-8190, 4914 – 48 Avenue, Red Deer. -

Ansteorran Achievment Armorial

Ansteorran Achievment Armorial Name: Loch Soilleir, Barony of Date Registered: 9/30/2006 Mantling 1: Argent Helm: Barred Helm argent, visor or Helm Facing: dexter Mantling 2: Sable: a semy of compass stars arg Crest verte a sea serpent in annulo volant of Motto Inspiration Endeavor Strength Translation Inspiration Endeavor Strength it's tail Corone baronial Dexter Supporter Sea Ram proper Sinister Supporter Otter rampant proper Notes inside of helm is gules, Sea Ram upper portion white ram, lower green fish. Sits on 3 waves Azure and Argent instead of the normal mound Name: Adelicia Tagliaferro Date Registered: 4/22/1988 Mantling 1: counter-ermine Helm: N/A Helm Facing: Mantling 2: argent Crest owl Or Motto Honor is Duty and Duty is Honor Translation Corone baronial wide fillet Dexter Supporter owl Or Sinister Supporter owl Or Notes Lozenge display with cloak; originally registered 4\22\1988 under previous name "Adelicia Alianora of Gilwell" Name: Aeruin ni Hearain O Chonemara Date Registered: 6/28/1988 Mantling 1: sable Helm: N/A Helm Facing: Mantling 2: vert Crest heron displayed argent crested orbed Motto Sola Petit Ardea Translation The Heron stands alone (Latin) and membered Or maintaining in its beak a sprig of pine and a sprig of mistletoe proper Corone Dexter Supporter Sinister Supporter Notes Display with cloak and bow Name: Aethelstan Aethelmearson Date Registered: 4/16/2002 Mantling 1: vert ermined Or Helm: Spangenhelm with brass harps on the Helm Facing: Afronty Mantling 2: Or cheek pieces and brass brow plate Crest phoenix -

Nature on Trial: the Case of the Rooster That Laid an Egg

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 10 Number 10 Civilizations East and West: A Article 7 Memorial Volume for Benjamin Nelson 1-1-1985 Nature on Trial: The Case of the Rooster That Laid an Egg E. V. Walter Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Recommended Citation Walter, E. V. (1985) "Nature on Trial: The Case of the Rooster That Laid an Egg," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 10 : No. 10 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol10/iss10/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Walter: Nature on Trial: The Case of the Rooster That Laid an Egg 5. Nature on Trial: The Case of the Rooster That Laid an Egg E. V. Walter In 1474, a chicken passing for a rooster laid an egg, and was prosecuted by law in the city of Basel. Now, we are inclined to dismiss the event as fowl play, but in those days lusus naturae was no joke. The animal was sentenced in a solemn judicial proceeding and condemned to be burned alive "for the heinous and unnatural crime of laying an egg." The execution took place "with as great solemnity as would have been observed in consigning a heretic to the flames, and was witnessed by an immense crowd of townsmen and peasants." 1 The same kind of prosecution took place in Switzerland again as late as 1730. -

Bush Shrikes to Old World Sparrows

15_123(3)BookReviews.qxd:CFN_123(3) 1/26/11 11:42 AM Page 271 2009 BOOK REVIEWS 271 Handbook of Birds of the World. Volume 14: Bush Shrikes to Old World Sparrows Edited by Josep del Hoyo, Andrew Elliott, and David Christie. Lynx Edicions, Montseny, 8, 08193 Bellaterra, Barcelona, Spain. 896 pages, 335 CAD Cloth. I normally jump to the species plates and descrip- I think, as they have shown these birds sitting on a tions, but this time I stopped at the foreword . This branch [a logical choice] and have foregone the magic essay on birding is dedicated to Max Nicholson, the of their display. There are wonderful photographs of man who took us from bird collecting to bird watching. birds in display, but you really need to be there or at Nicholson was also instrumental in the creation and least watch a video to see these spectacles in their growth of many initiatives like the British Trust for true, shimmering glory. There are about 80 photos of Ornithology, the World Wildlife Fund, and the Royal birds-of-paradise, 40% of which were contributed by Society for the Protection of Birds. The essay “Bird- two men, Tim Lehman and Brian Coates. These photos ing Past, Present and Future: a Global View ” by show almost 90% of the species . Stephen Moss is an overview history of birdwatching The second family is the crows. These birds are from the pre-binocular era to the present. It gives a easier to depict , as many are black, sometimes with fascinating look at our cherished hobby [or is that reli- white or grey, although the jays can be remarkably col- gion?] using a broad frame of reference. -

Ethno–Ornithology and History of the Mapuche Fowl

Revista Chilena de Ornitología 22(1): 126-132 Unión de Ornitólogos de Chile 2016 CONTRIBUCIÓN BREVE 126 EDICIÓN ESPECIAL: ETNO–ORNITOLOGÍA ETHNO–ORNITHOLOGY AND HISTORY OF THE MAPUCHE FOWL Etno–ornitología e historia de la gallina mapuche JOSÉ ANTONIO ALCALDE1 1Facultad de Agronomía e Ingeniería Forestal, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Santiago, Chile. Correspondence: [email protected]. RESUMEN.– El estado de conservación de la gallina mapuche, que incluye los subtipos collonca y quetro, es- taba seriamente amenazado a fines del siglo pasado. Su presencia en comunidades mapuche en la Región de La Araucanía era escasa y su empleo en rogativas como el Nguillatun era solo esporádico y desconocido para las nuevas generaciones. En este trabajo se da cuenta de su etno–ornitología, su historia y del modo de herencia de sus caracteres morfológicos, que podrían explicar la alarmante disminución de su población durante el siglo pa- sado, y su recuperación sostenida durante los últimos años. Prospecciones a principios de este siglo (2000–2004) daban cuenta de individuos aislados dentro de planteles caseros en localidades rurales apartadas. El tipo más escaso era la gallina quetro (con aretes), presente solamente en cinco localidades, todas ellas fuera de la Región de La Araucanía. La conservación ex situ por clubes especializados en Norteamérica y Europa, a partir de un reducido número de individuos importados durante la primera mitad del siglo XX ha seguido directrices de ex- hibición más que de preservación genética de la raza. El rescate y multiplicación de ejemplares remanentes y su reintroducción a comunidades mapuche, junto al apoyo en difusión por programas de televisión, han potenciado una rápida revalorización de colloncas y quetros, y sobre todo una importante recuperación de la memoria ances- tral de su rol para el pueblo mapuche. -

Livestock Definitions

ONATE Useful livestock terms Livestock are animals that are kept for production or lifestyle, such as cattle, sheep, pigs, goats, horses or poultry. General terms for all livestock types Dam – female parent Sire – male parent Entire – a male animal that has not been castrated and is capable of breeding Weaning – the process of separation of young animals from their mothers when they are no longer dependent upon them for survival Cattle Cattle are mainly farmed for meat and milk. Bovine – refers to cattle or buffalo Cow – a female bovine that has had a calf, or is more than three years old Bull – an entire male bovine Calf – a young bovine from birth to weaning (six–nine months old) o Bull calf – a male calf o Heifer calf – a female calf Steer – a castrated male bovine more than one year old Heifer – a female bovine that has not had a calf, or is aged between six months and three years old Calving – giving birth Herd – a group of cattle Sheep Sheep are farmed for meat and fibre (wool) and sometimes milk. Ovine – refers to sheep Ram – entire male sheep that is more than one year old Ewe – a female sheep more than one year old Lamb – a young sheep less than one year old NOTE – When referring to meat, lamb is meat from a sheep that is 12–14 months old or less o Ewe lamb – is a female sheep less than one year old o Ram lamb – is a male sheep less than one year old Weaner – a lamb that has been recently weaned from its mother Hogget – a young sheep before it reaches sexual maturity – aged between nine months and one year Wether – a castrated male sheep Lambing – giving birth Flock / Mob – a group of sheep AgLinkEd Education Initiative – Department of Agriculture and Food, Western Australia Email: [email protected] Website: agric.wa.gov.au/education Pigs Pigs are mainly farmed for meat. -

Scientist's Observation Form

Scientist’s Observation Form Scientist’s Name __________________________________ Today’s Date ______________________________________ I looked at _________________________________________________ Here is a picture of what I saw: This animal’s color is _______________________ When I saw this animal, it was _____________________________________ I wonder: Spend a few minutes watching each of the Zoo’s primates. Put an X through the behaviors you observe. Taking a Closer Look Stop at two different animal habitats. Pick out a single animal to observe and describe it so that someone else could identify that animal. Watch for at least five minutes. Try to list or describe the behavior you observe without guessing what that behavior means. Remember, we can’t know what an animal is thinking, just what it is doing. HABITAT 1 Description of animal under observation: Time Start ___________ Time Stop ____________ Behavior observed: HABITAT 2 Description of animal under observation: Time Start ___________ Time Stop ____________ Behavior observed: ZOO MATH Math at the Zoo? Of course. Math is everywhere! Using the Zoo as a guide, calculate a solution to each problem. 1. The Zoo’s elephants EACH eat 75 pounds of hay per day. There are ____ elephants at the Zoo. How many pounds of hay does the Zoo need to to feed its elephants per day? How many pounds per week? _____ pounds per day _____ pounds per week 2. You could fit 24 chicken eggs in one ostrich egg. There are ____ female ostrich at the Zoo. If each ostrich laid 2 eggs, how many chicken eggs would that equal? Hint: all the Zoo’s ostrich are female. -

Sound Localization in Birds - Physical and Neurophysiological Mechanisms of Sound Localization in the Chicken

Technische Universität München Lehrstuhl für Zoologie Sound Localization in Birds - Physical and Neurophysiological Mechanisms of Sound Localization in the Chicken Hans A. Schnyder Vollständiger Abdruck der von der Fakultät Wissenschaftszentrum Weihenstephan für Ernährung, Landnutzung und Umwelt der Technischen Universität München zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften genehmigten Dissertation. Vorsitzender: Prof. Dr. Rudolf Fries Prüfer der Dissertation: 1. Prof. Dr. Harald Luksch 2. Prof. Dr. Bernhard Seeber Die Dissertation wurde am 09.08.2017 bei der Technischen Universität München eingereicht und durch die Fakultät Wissenschaftszentrum Weihenstephan für Ernährung, Landnutzung und Umwelt am 22.01.2018 angenommen. Summary Accurate sound source localization in three-dimensional space is essential for an animal’s orientation and survival. While the horizontal position can be determined by interaural time and intensity differences, localization in elevation was thought to require external structures that modify sound before it reaches the tympanum. Here I show that in birds even without external structures such as pinnae or feather ruffs, the simple shape of their head induces sound modifications that depend on the elevation of the source. A model of localization errors shows that these cues are sufficient to locate sounds in the vertical plane. These results suggest that the head of all birds induces acoustic cues for sound localization in the vertical plane, even in the absence of external ears. Based on these findings, I investigated the neuronal processing of spatial acoustic cues in the midbrain of birds. The avian midbrain is a computational hub for the integration of auditory and visual information. While at early stages of the auditory pathway time and intensity information is processed separately, information from both streams converges at the inferior colliculus (IC). -

Raising Poultry: Preventing Loss by Bears

New Hampshire Fish and Game Department EXAMPLES OF ENERGIZERS AND FENCING COMPONENTS MATERIALS RAISING WORKSHEET POULTRY IN NEW HAMPSHIRE FENCING • Poultry Net Fence $93-$200 PREVENTING LOSS BY BEARS • Fence Conductor $17-$66 ENERGIZERS • Solar $190-$360 • Battery $89-$233 • 110 Volt $95-$200 POSTS • Tread-ins $3 each ACCESSORIES • Voltage Tester $13-$112 • Insulators $.45-$.88 • Ground Rod $8-$11 • Ground Rod Clamp $3 • Warning Signs $3 Reported Bear/Poultry Complaints in NH 2005-2017 200 180 The products and price ranges provided in this brochure 160 140 are intended for reference only. The N.H. Fish and Game 120 Department or USDA Wildlife Services do not endorse 100 or guarantee the use of these products over others not 80 mentioned. Contact your local fence dealer for specific 60 pricing and additional options. Number of Complaints 40 20 For more information, please contact the 0 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 USDA Wildlife Services office at 603-223-6832. BER18001.indd KEEPING BEARS OUT REQUIRES EFFECTIVE ELECTRIC RECOMMENDED PRACTICES A DIFFERENT APPROACH FOR PROTECTING POULTRY FENCE OPTIONS The popularity of raising backyard chickens and waterfowl has Electric fencing represents a modest investment that will • Utilize electric fence around poultry coops, pens, grown significantly in recent years, as people became interested in provide years of service protecting poultry from bears. and runs. providing their own meat and fresh eggs. If poultry is not adequately • Keep the electric fence in good condition to contained and protected, loss to wildlife should be expected. Animals COMPONENT FENCING ensure it is working properly.