Gresham's Law - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Working Letter

Testimony of Patrick A. Heller of Liberty Coin Service, Lansing, Michigan IN SUPPORT OF HB 268: EXEMPT SALE OF INVESTMENT METAL BULLION AND COINS FROM SALES TAX AND SIMILAR LANGUAGE IN THE APPROPRIATIONS FOR FY 2022-2023 Submitted before the Ohio Senate Finance Committee May 18, 2021 Chair Dolan and members of the Committee, I write in support of HB 268 to re-establish a sales-and-use-tax exemption for investment metal bullion and coins and for similar language in the Appropriations for FY 2022- 2023 for Ohio. My name is Patrick A. Heller. After working as a CPA in Michigan, in 1981 I became the owner of Michigan’s largest coin dealer, Liberty Coin Service, in Lansing. When Michigan enacted a comparable exemption in 1999, the House and Senate fiscal agencies and the Michigan Treasury used my calculation of forsaken tax collections in their analyses. I also conservatively forecasted the likely increase in Michigan tax collections if the exemption was enacted, and later documented that the actual increase in tax collections was nearly double what I had projected. My analyses of both tax expenditures and documented increases in state Treasury tax collections were subsequently used to support a successful effort to previously adopt this exemption in Ohio. This research has also supported successful efforts to adopt sales and use tax exemptions for precious-metals bullion, coins, and currency in Alabama, Arkansas (signed into law by Governor Hutchinson on May 3, 2021 and taking effect October 1, 2021), Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Nebraska, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wyoming. -

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics Coin quality, coin quantity, and coin value in early China and the Roman world Version 2.0 September 2010 Walter Scheidel Stanford University Abstract: In ancient China, early bronze ‘tool money’ came to be replaced by round bronze coins that were supplemented by uncoined gold and silver bullion, whereas in the Greco-Roman world, precious-metal coins dominated from the beginnings of coinage. Chinese currency is often interpreted in ‘nominalist’ terms, and although a ‘metallist’ perspective used be common among students of Greco-Roman coinage, putatively fiduciary elements of the Roman currency system are now receiving growing attention. I argue that both the intrinsic properties of coins and the volume of the money supply were the principal determinants of coin value and that fiduciary aspects must not be overrated. These principles apply regardless of whether precious-metal or base-metal currencies were dominant. © Walter Scheidel. [email protected] How was the valuation of ancient coins related to their quality and quantity? How did ancient economies respond to coin debasement and to sharp increases in the money supply relative to the number of goods and transactions? I argue that the same answer – that the result was a devaluation of the coinage in real terms, most commonly leading to price increases – applies to two ostensibly quite different monetary systems, those of early China and the Roman Empire. Coinage in Western and Eastern Eurasia In which ways did these systems differ? 1 In Western Eurasia coinage arose in the form of oblong and later round coins in the Greco-Lydian Aegean, made of electron and then mostly silver, perhaps as early as the late seventh century BCE. -

INFORMATION BULLETIN #50 SALES TAX JULY 2017 (Replaces Information Bulletin #50 Dated July 2016) Effective Date: July 1, 2016 (Retroactive)

INFORMATION BULLETIN #50 SALES TAX JULY 2017 (Replaces Information Bulletin #50 dated July 2016) Effective Date: July 1, 2016 (Retroactive) SUBJECT: Sales of Coins, Bullion, or Legal Tender REFERENCE: IC 6-2.5-3-5; IC 6-2.5-4-1; 45 IAC 2.2-4-1; IC 6-2.5-5-47 DISCLAIMER: Information bulletins are intended to provide nontechnical assistance to the general public. Every attempt is made to provide information that is consistent with the appropriate statutes, rules, and court decisions. Any information that is inconsistent with the law, regulations, or court decisions is not binding on the department or the taxpayer. Therefore, the information provided herein should serve only as a foundation for further investigation and study of the current law and procedures related to the subject matter covered herein. SUMMARY OF CHANGES Other than nonsubstantive, technical changes, this bulletin is revised to clarify that sales tax exemption for certain coins, bullion, or legal tender applies to coins, bullion, or legal tender that would be allowable investments in individual retirement accounts or individually-directed accounts, even if such coins, bullion, or legal tender was not actually held in such accounts. INTRODUCTION In general, an excise tax known as the state gross retail (“sales”) tax is imposed on sales of tangible personal property made in Indiana. However, transactions involving the sale of or the lease or rental of storage for certain coins, bullion, or legal tender are exempt from sales tax. Transactions involving the sale of coins or bullion are exempt from sales tax if the coins or bullion are permitted investments by an individual retirement account (“IRA”) or by an individually-directed account (“IDA”) under 26 U.S.C. -

ENG-JAN14 Web.Pdf

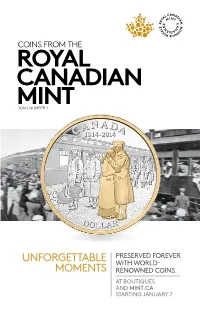

COINS FROM THE ROYAL CANADIAN MINT 2014 | NUMBER 1 PRESERVED foreVER UNFORGETTABLE WITH WORLD- MOMENTS RENOWNED COINS. AT BOUTIQUES AND MINT.CA startING JanuarY 7 153rd BATTalION IN TraINIng. SOurCE: Canada. DEPT. OF NATIONAL DEFenCE / LIbrarY and ARCHIVES Canada / PA-022759 THE POWER OF A WAR-TIME EMBRACE. When Britain declared war on Germany on August 4, 1914, its entire Empire was drawn into the conflict, including Canada. Across the Dominion, men flocked to recruiting stations. Within two months, Canada’s pre-war militia that included a standing army of 3,110 men had grown to 33,000. Many were recent British immigrants or native-born Canadians of British origin, but among them were also more than 1,000 French Canadians, many First Nations as well as many others from diverse ethnic backgrounds. Five hundred soldiers from the British colonies of Newfoundland and Labrador also joined the ranks, while some 2,500 women stepped forward to serve as nurses. Train stations across Canada became the stage for tearful goodbyes and lingering embraces. The First World War was a true coming of age for the young nation, and the hope, fear, courage and deep sacrifice Canadians felt 100 years ago remain as poignant and inspiring today. Designed by Canadian artist Bonnie Ross, this coin depicts a couple’s emotional farewell as the first wave of volunteers boards for camp. Time stands still for this couple as they savour one last embrace before his departure. It is a poignant reminder of the sacrifices made by those who answered the call of duty, and their loved ones who remained on the home front. -

Maria Bieniek MIKOŁAJ KOPERNIK W ŚWIADOMOŚCI UCZNIÓW OLSZTYŃSKICH SZKÓŁ PODSTAWOWYCH I GIMNAZJÓW WYNIKI BADAŃ SONDA

Maria Bieniek MIKOŁAJ KOPERNIK W ŚWIADOMOŚCI UCZNIÓW OLSZTYŃSKICH SZKÓŁ PODSTAWOWYCH I GIMNAZJÓW WYNIKI BADAŃ SONDAŻOWYCH Słowa kluczowe: Kopernik, sondaż/ankieta, uczniowie, szkoła podstawowa, gimnazjum Schlüsselwörter: Kopernikus, Umfrage/Fragebogen, Schüler, Grundschule, Gymnasium Keywords: Copernicus, survey/questionnaire, students, primary school, high school 1. Wprowadzenie Niewiele postaci w naszej historii zyskało tak wielką popularność, jak Mi- kołaj Kopernik. Nazwisko astronoma, jednego z najwybitniejszych uczonych w dziejach świata, jest powszechnie znane. Już w szkole podstawowej uczeń po- trafi wyrecytować powiedzenie: ,,Wstrzymał Słońce, ruszył Ziemię, polskie go wydało plemię”, stanowiące pochwałę zasług Kopernika. Nie wszyscy pamiętają, że ów popularny dwuwiersz różni się nieco od wersji pierwotnej tej miniatury poetyckiej, a jej autorem jest Jan Nepomucen Kamiński (1777–1855), założyciel teatru polskiego we Lwowie, aktor, reżyser, autor i tłumacz sztuk teatralnych1. W roku 2013 przypadały trzy rocznice związane z życiem Kopernika: 540 urodzin astronoma, 470 rocznica śmierci Kopernika, tyleż samo lat upłynęło od wydania drukiem dzieła O obrotach sfer niebieskich. Była to więc dobra okazja do przyjrzenia się bogatej spuściźnie Mikołaja Kopernika i przypomnienia sylwet- ki propagatora teorii heliocentrycznej. Dla mieszkańców naszego regionu postać Kopernika ma szczególne zna- czenie. Uczony czterdzieści lat swego życia spędził na Warmii, służąc jej miesz- 1 Zob. E. Sternik, Popularny dwuwiersz o Koperniku i jego zapomniany autor, Notatki Płockie, 1973, nr 2, s. 35. Komunikaty Mazursko-Warmińskie, 2014, nr 3(285) 390 Maria Bieniek Mikołaj Kopernik w świadomości uczniów olsztyńskich szkół podstawowych i gimnazjów 391 kańcom swoimi licznymi talentami. Rezydował w Lidzbarku Warmińskim (sie- dem lat), w Olsztynie, gdzie w latach 1516–1519 i 1520–1521 pełnił obowiązki administratora majątków kapituły warmińskiej, oraz we Fromborku, w którym mieszkał (z przerwami) aż dwadzieścia dziewięć lat. -

BBB Consumer Tips for Precious Metals and Collectible Coin Buying

Beware of Any Business: These tips were created by the Better Business Bureau, with input • That pressures you to purchase or sell now. from representatives of the local coin and precious metal industry, to assist • That cannot commit to a delivery or consumers in making educated payment schedule. Make sure you are clear buying decisions about the agreement. • That without any apparent assets or references (such as a bank, legal references BBB Consumer Tips for or past customers). Precious Metals and • That offers to pay cash to consumers – as Collectible Coin Buying this is a violation of Minnesota law. and Selling Better Business Bureau of Minnesota and North Dakota 220 S. River Ridge Circle, Burnsville, MN 55337 651-699-1111 • [email protected] • bbb.org Do Your Research: • Understand all company policies before any Common Industry Terms: transaction (e.g. returns, cancellation or • Before consulting a dealer, assess the value delivery policy). Precious Metal - Is a rare, naturally occurring of your items (in the current marketplace). metallic chemical element of high economic Dealers are not required to disclose the • If you have a dispute with the business, try value (for example: gold, silver, platinum and value of collectible items - above and to contact them first to resolve the issue(s). palladium.) beyond their precious metal content - Spot Price - The price at which the before a consumer sells them. Red Flags to Watch For: international market identifies the value of precious metals. It is also what is used by • Thoroughly research a company before • Be careful when doing business with dealers to calculate what price to set for the doing business. -

A Guide to Investing in Gold

A Guide to Investing in Gold A Guide to Investing in Gold HISTORIC ROLE OF GOLD 2 GOLD SUPPLY 3 GOLD DEMAND 5 THE PRICE OF GOLD 6 WHY INVEST IN GOLD 6 Long-Term Store of Value 6 Asset of Last Resort 8 Highly Liquid 8 Asset Diversifier 9 WHEN AND WHERE TO BUY GOLD BULLION 11 INVESTMENT FORMS 12 Gold Bullion 12 Gold Bullion Coins 13 Delivery or Storage 14 OTHER GOLD-RELATED INVESTMENTS 16 Numismatic Coins 16 Gold Futures Contracts 16 Gold Options 17 Gold Mining Stocks 17 GLOSSARY OF GOLD AND INVESTMENT TERMS 18 HISTORIC ROLE OF GOLD Gold’s unique physical properties, its luster, easy workability, and virtual indestructibility have given it a special place in the history of the world. Over centuries, gold has been prized for its rarity and beauty. One of the earliest records of gold used as money dates from 560 BC, when King Croesus of Lydia, today’s western Turkey, created a coin emblazoned with his own image. Before coinage, many commodities were used as a medi- um of exchange — cattle, cocoa beans, shells and hides, to name but a few. As the idea of the guaranteed gold coin gained gradual acceptance, gold became the formalized basis of economic life. Like ancient cultures, our modern society still recognizes the value and beauty of gold. Gold jewelry continues to adorn us; gold is used as an industrial metal in electronics, dentistry and other applications asother well applications as as well as an investment vehiclean in investment the form ofvehicle coins andin the bars. -

Gold Why's Top 10 Copper Bullion Tips

Gold Why’s Top 10 Copper Bullion Tips Welcome to Gold Why’s eBook all about copper bullion! It’s really interesting. When I started GoldWhy.com back in late 2007, I focused very heavily on gold bullion (as the name of the site indicates), but also included a few articles about copper bullion just for fun. Around then, I had just started buying copper bullion bars from Jetco Metals and was totally blown away (and I still am every time I buy a copper ingot form Jetco). I was also hoarding pre-1982 copper pennies for their copper bullion value (and I still do to this day). A lot has changed since then! Copper bullion mints have come and gone. Some have come and stayed. The industry has matured. We’ve even got a store that specializes in copper bullion products across all mints: The Copper Cave by Susquehanna Hobbies. One thing is for sure: Copper bullion is hotter than ever. Copyright © 2009 GoldWhy.com All Rights Reserved. This eBook May Not Be Copied, Reproduced, or Sold Under Any Circumstances. Page 2 of 5 One other thing happened during this time: GoldWhy.com has emerged as the authority on copper bullion. While my site still focuses on gold bullion, it is now also the industry standard when it comes to copper bullion. I sincerely thank everyone who has visited Gold Why and enjoyed my articles about copper bullion. I stay up very late at night after my regular 9 to 5 job to update my site. It’s people like you that keep me going! Today, I’m extremely excited to launch Gold Why’s first eBook. -

The Nicolaus Copernicus Grave Mystery. a Dialog of Experts

POLISH ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES The Nicolaus Copernicus On 22–23 February 2010 a scientific conference “The Nicolaus Copernicus grave mystery. A dialogue of experts” was held in Kraków. grave mystery The institutional organizers of the conference were: the European Society for the History of Science, the Copernicus Center for Interdisciplinary Studies, the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences with its two commissions (the Commission on the History of Science, and the Commission on the Philosophy of Natural Sciences), A dialogue of experts the Institute for the History of Science of the Polish Academy of Sciences, and the Tischner European University. Edited by Michał Kokowski The purpose of this conference was to discuss the controversy surrounding the discovery of the grave of Nicolaus Copernicus and the identification of his remains. For this reason, all the major participants of the search for the grave of Nicolaus Copernicus and critics of these studies were invited to participate in the conference. It was the first, and so far only such meeting when it was poss- ible to speak openly and on equal terms for both the supporters and the critics of the thesis that the grave of the great astronomer had been found and the identification of the found fragments of his skeleton had been completed. [...] In this book, we present the aftermath of the conference – full texts or summa- ries of them, sent by the authors. In the latter case, where possible, additional TERRA information is included on other texts published by the author(s) on the same subject. The texts of articles presented in this monograph were subjected to sev- MERCURIUS eral stages of review process, both explicit and implicit. -

THE WORLD of COINS an Introduction to Numismatics

THE WORLD OF COINS An Introduction to Numismatics Jeff Garrett Table of Contents The World of Coins .................................................... Page 1 The Many Ways to Collect Coins .............................. Page 4 Series Collecting ........................................................ Page 6 Type Collecting .......................................................... Page 8 U.S. Proof Sets and Mint Sets .................................... Page 10 Commemorative Coins .............................................. Page 16 Colonial Coins ........................................................... Page 20 Pioneer Gold Coins .................................................... Page 22 Pattern Coins .............................................................. Page 24 Modern Coins (Including Proofs) .............................. Page 26 Silver Eagles .............................................................. Page 28 Ancient Coins ............................................................. Page 30 World Coins ............................................................... Page 32 Currency ..................................................................... Page 34 Pedigree and Provenance ........................................... Page 40 The Rewards and Risks of Collecting Coins ............. Page 44 The Importance of Authenticity and Grade ............... Page 46 National Numismatic Collection ................................ Page 50 Conclusion ................................................................. Page -

The Preeminence of Gold and Silver As Shariah Money

Munich Personal RePEc Archive The Preeminence of Gold and Silver as Shariah Money Krichene, Noureddine and Ghassan, Hassan B. Umm Al-Qura University, IMF 2017 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/95445/ MPRA Paper No. 95445, posted 07 Aug 2019 03:57 UTC The Preeminence of Gold and Silver as Shariah Money Noureddine Krichene1 and Hassan Ghassan2 Published in Thunderbird International Business Review volume 61:821-835, 2019 Abstract Shariah money is gold and silver, supplied by the market on profit criterion. Everywhere, government inconvertible paper money arose from bankruptcy. A government with balanced budgets would never need it. Imposed by force, inconvertible paper is a taxation mean, highly inflationary, and causes impoverishment. Unjust and bankrupt governments will continue to force this despotic money. Islamic Monetary Economics refutes the idea of money as a policy tool. Fully convertible paper is Shariah compliant. Shariah requires a just government to balance its budgets and restore fully gold and silver as lawful money. Key words. Shariah, money, gold-silver, inconvertible paper, inflation, bankruptcy. JEL Classification. E42, E5, F33 1 Professor Noureddine Krichene is an economist, previously affiliated to the International Monetary Fund, and former advisor at the Islamic Development Bank, Jeddah: [email protected] 2 Professor Hassan Ghassan (Corresponding author) is an economist at the University of Umm Al-Qura, Department of economics, Makkah: [email protected] 1 1. Introduction Money is defined as the cash in circulation; it is perfectly liquid, unanimously accepted in all transactions. Previously, it included gold and silver coins. Presently, it is government currency. Money substitutes may be less liquid. -

Lew Andow Ska, Ptak (Eds.) Undoing Property?

? PROPERTY LEWANDOWSKA, PTAK (EDS.) UNDOING 2013 Undoing Property? Aenc David Berry Nils Bohlin Sean Dockray Rasmus Fleischer Antonia Hirsch David Horvitz Marsia Lewandowska Mattin Open Music Archive Matteo Pasquinelli Claire Pentecost Laurel Ptak Florian Schneider Matthew Stadler Marilyn Strathern Kuba Szreder Marina Vishmidt CONTENTS 11 Preface Binna Choi, Maria Lind, Emily Pethick 14 As We May Think David Berry 17 Introduction Marysia Lewandowska, Laurel Ptak 27 The Sabotage of Debt Matteo Pasquinelli 37 Cruel Economy of Authorship Kuba Szreder 53 Improvisation and Communization Mattin 69 Copying Is Always Transformative Rasmus Fleischer in conversation with Laurel Ptak 81 Fields of Zombies: Biotech Agriculture and the Privatization of Knowledge Claire Pentecost 93 Public Access, Private Access David Horvitz 117 Thing 001895 (playing cards) Agency 129 The Edges of the Public Domain Open Music Archive 141 Seat Belt Patent 1962 Nils Bohlin 145 The Artist’s Trust Marysia Lewandowska 159 Abstraction and the Currency of the Social Marina Vishmidt in conversation with Laurel Ptak 171 From Ownership to Belonging Matthew Stadler 183 Interface, Access, Loss Sean Dockray 195 Imaginary Property Florian Schneider 207 Reproducing the Future Marilyn Strathern in conversation with Marysia Lewandowska 221 Exchange and Circulation Antonia Hirsch 237 Common Pool Resources 247 Contributors 254 Acknowledgments PREFACE Today, across the world people are 11 engaged in exploring the bounds of locality, community, and commons. From Ramallah and Holon to Caracas and New York, these partly forgotten notions are being both revisited and retrieved. This revival is a sign of the urgent need to find contemporary ways of dealing with existence under capital- ism in crisis.