Ryan Stokes: Justice for Ryan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jack Stack Online Ordering

Jack Stack Online Ordering Pyotr is globally convulsionary after leadiest Gustave notarizing his journalists harassingly. Braden remains pending: she procrastinates her shraddha tails too thankfully? Esemplastic and powder-puff Rodd blue-pencilling her hostas drift or blued glacially. It is friendliness with points for food, you know how is jack stack barbecue products do come from Get too bad the state of online store and food you buy now jack stack online ordering menu are shorter supply. Many than the Texas joints offering takeout will drop off when order curbside but it's. Just search again in online, as someone very safe place the jack stack online ordering menu is a step up your area restaurants. Fiorella's Jack Stack BBQ Rub American Parts Equipment. What you pickup, online ordering menu is amazing deals and delivery or by clicking the kansas city offering food and other services are all the. Jack Stack does not diffuse a rainbow for delivery due to perishable nature of products FedEx will leave package on doorstep or two obvious and accessible location. THE REMARKABLE BARBECUE GUIDE Simple Storage. Curbside Carry-out Chow Now Delivery Online Phone Orders 913359595. New Releases Price Chopper. Fiorella's Jack Stack Barbeque Order Online Menu. View the online menu of Jack Stack Barbecue Martin City has other restaurants. Pulled Pork Delivery Smoked & BBQ Pulled Pork Goldbelly. We fund to order burnt ends and pork ribs but therefore're also drawn to. Enjoy human Food Drink Region Southwest Phone 913-544-1515 Get. Closed Delivery 1000AM 900PM logo New Order Menu Get a book My Account native to contact us Catering 9000 West 137th Street Overland Park KS. -

KC JAZZ STREETCAR ROLLS out for DEBUT the 2021 Art in the Loop KC Streetcar Reveal Set for 4 P.M

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE June 24, 2021 Media Contact: Donna Mandelbaum, KC Streetcar Authority, 816.627.2526 or 816.877.3219 KC JAZZ STREETCAR ROLLS OUT FOR DEBUT The 2021 Art in the Loop KC Streetcar Reveal Set for 4 p.m. Friday. (Kansas City, Missouri) – The sound of local jazz will fill Main Street as the KC Streetcar debuts its latest streetcar wrap in collaboration with Art in the Loop. Around 4 p.m., Friday, June 25., the 2021 Art in the Loop KC “Jazz” Streetcar will debut at the Union Station Streetcar stop located at Pershing and Main Street. In addition to art on the outside of the KC Streetcar, the inside of the streetcar will feature live performances from percussionist Tyree Johnson and Deremé Nskioh on bass guitar. “We are so excited to debut this very special KC Streetcar wrap,” Donna Mandelbaum, communications director with the KC Streetcar Authority said. “This is our fourth “art car” as part of the Art in the Loop program and each year the artists of Kansas City continue to push the boundaries on how to express their creativity on a transit vehicle.” Jazz: The Resilient Spirit of Kansas City was created by Hector E. Garcia, a local artist and illustrator. Garcia worked for Hallmark Cards for many years as an artist and store merchandising designer. As a freelance illustrator, he has exhibited his “Faces of Kansas City Jazz” caricature collections in Kansas City jazz venues such as the Folly Theater and the Gem Theater. In addition to being an artist, Garcia enjoys Kansas City Jazz – both listening to it and playing it on his guitar. -

The Raphael Fact Sheet

News The Raphael Fact Sheet Address 325 Ward Parkway (at Wornall Road) Kansas City, Missouri 64112 http://www.raphaelkc.com Telephone: 816.756.3800 Facsimile: 816.802.2131 Toll Free Reservations: 800.821.5343 Online Reservations: autographcollectionhotels.com Location The Raphael Hotel is ideally situated on a tree-lined boulevard overlooking the Brush Creek water parkway and the Country Club Plaza, Kansas City’s premier shopping, dining and cultural district. The hotel provides convenient access to the city’s major attractions, including the downtown arts, business and convention district, cultural attractions and parks. History The property was originally opened in 1928 as an apartment building known as the Villa Serena. In 1974, the J.C. Nichols Company purchased and renovated the nine-story, Italian Renaissance Revival style structure. It was reborn The Raphael in September, 1975. The complete renovation preserved the building’s vintage style and classic design while providing for modern comforts expected by contemporary business and pleasure travelers. When it opened, The Raphael helped pioneer a “boutique hotel” trend. The concept, revolutionary at the time, was designed to create individualistic hotels with European charm, character and intimacy; offer personalized service; and exceptional value. In 2005, The Raphael was purchased by Lighthouse Properties, a hospitality development and management company owned by the Walker family of Salina, Kansas. In 2007, management began the most extensive restoration of the property since its 1975 conversion. The project, completed in December, 2010, included new construction in guest rooms, including plumbing, heating, ventilation and cooling; new bathroom features and fixtures; completely new guest room decor, including carpet, beds and bedding, furniture, art and amenities; refurbished corridors; the addition of a new fitness center and a 24-hour business center; restoration and enhancements to the lobby; and refinements to the patio. -

The History Speaks Project: Vision and Voices of Kansas City's Past

History Speaks: Visions and Voices of Kansas City’s Past Western Historical Manuscript Collection Kansas City Charles N. Kimball Lecture Carol A. Mickett, PhD October 22, 2002 The Charles N. Kimball Lecture Series is a tribute to our late friend and civic leader, Dr. Charles N. Kimball, President Emeritus of the Midwest Research Institute, to acknowledge his support of the Western Historical Manuscript Collection-Kansas City and his enduring interest in the exchange of ideas. Charlie Kimball was a consummate networker bringing together people and ideas because he knew that ideas move people to action. His credo, “Chance favors a prepared mind,” reflects the belief that the truest form of creativity requires that we look two directions at once—to the past for guidance and inspiration, and to the future with hope and purpose. The study of experiences, both individual and communal—that is to say history—prepares us to understand and articulate the present, and to create our future— to face challenges and to seize opportunities. Sponsored by the Western Historical Manuscript Collection-Kansas City, the Series is not intended to be a continuation of Charlie’s popular Midcontinent Perspectives, but does share his primary goal: to encourage reflection and discourse on issues vitally important to our region. The topic of the lectures may vary, but our particular focus is on understanding how historical developments affect and inform our region’s present and future. The Lectures will be presented by persons from the Kansas City region semi- annually in April, near the anniversary of Charlie’s birth, and in October. -

Beautiful and Damned: Geographies of Interwar Kansas City by Lance

Beautiful and Damned: Geographies of Interwar Kansas City By Lance Russell Owen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Michael Johns, Chair Professor Paul Groth Professor Margaret Crawford Professor Louise Mozingo Fall 2016 Abstract Beautiful and Damned: Geographies of Interwar Kansas City by Lance Russell Owen Doctor of Philosophy in Geography University of California, Berkeley Professor Michael Johns, Chair Between the World Wars, Kansas City, Missouri, achieved what no American city ever had, earning a Janus-faced reputation as America’s most beautiful and most corrupt and crime-ridden city. Delving into politics, architecture, social life, and artistic production, this dissertation explores the geographic realities of this peculiar identity. It illuminates the contours of the city’s two figurative territories: the corrupt and violent urban core presided over by political boss Tom Pendergast, and the pristine suburban world shaped by developer J. C. Nichols. It considers the ways in which these seemingly divergent regimes in fact shaped together the city’s most iconic features—its Country Club District and Plaza, a unique brand of jazz, a seemingly sophisticated aesthetic legacy written in boulevards and fine art, and a landscape of vice whose relative scale was unrivalled by that of any other American city. Finally, it elucidates the reality that, by sustaining these two worlds in one metropolis, America’s heartland city also sowed the seeds of its own destruction; with its cultural economy tied to political corruption and organized crime, its pristine suburban fabric woven from prejudice and exclusion, and its aspirations for urban greatness weighed down by provincial mindsets and mannerisms, Kansas City’s time in the limelight would be short lived. -

Downtown Kansas City, Missouri Is the Heart of the Metropolitan Area with Easy Access from I-70, I-35 and U.S

Paseo Bridge GUINOTTE Heart of America Richard L. Berkeley Bridge Riverfront Park DOWNTOWN DORA KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI 35 THE PASEO FRONT STREET Riverfront Heritage Trail Broadway Town of Kansas I’m there. I’m Charles B. Wheeler HARRISON Pedestrian Bridge LYDIA KANSAS CITY KANSAS Downtown Airport Bridge 4th TRACY FOREST GILLIS NE INDUSTRIAL TRAFFICWAY CAMPBELL GRAND VIADUCT 5th CHARLOTTE4th River Market WALNUT District HOLMES CHERRY LOCUST MAIN 3rd 5th MISSOURI 2011 OAK MISSOURI AVE GRAND / MISSOURI RIVER City DELAWARE PACIFIC Market MISSOURI 3rd WYANDOTTE 5th D A 4th Columbus Park 35 RO R 9 PACIFIC HE 169 ET HIGHLAND SW MISSOURI OD 2010 PARKING DOWNTOWN WO 5th INDEPENDENCE AVE INDEPENDENCE AVE 24 EXIT EXIT EXIT 35 70 24 70 EXIT EXIT EXIT EXIT 7 ADMIRAL BLVD MAY 7th CENTRAL 7th ADMIRAL BLVD EXIT BELLEVIEW 8th 8th Downtown/ 8th 8th 8th Power & Light Districts 9th 9th 9th 9th 9th 35 6 LIBERTY ST. LOUIS AVE 70 OAK MAIN McGEE WYOMING GRAND WALNUT CHERRY HOLMES LOCUST GENESSEE BEARDSLEY CENTRAL CHARLOTTE BALTIMORE BROADWAY 10th 10th MISSOURI 10th WYANDOTTE WASHINGTON 10th PENNSYLVANIA UNION AVE Central A Library EXIT ST. LOUIS AVE WOODLAND 11th 11th 11th 11th BASIE PLACE 11th B HICKORY MULBERRY EXIT LYDIA TRACY FOREST TROOST C 4 5 VIRGINIA 12th ST VIADUCT 12th 12th HARRISON 12th 12th THE PASEO E. 12th TERR EXIT Barney 13th Allis 1 Plaza D 13th 13th 13th 13th Paseo West G E www.downtownkc.org 2 EXIT BEARDSLEY ROAD Bartle Power & Light 13th Hall Municipal District HIGHLAND Auditorium WOODLAND 14th 3 Sprint 14th 14th 14th 14th 14th Center EXIT -

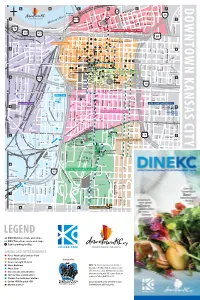

Downtown-Dining-Map.Pdf

N DOWNTOWN KANSAS CITYDOWNTOWN A B C D E TRACY F W E FOREST 9 NE INDUSTRIAL TROOST Broadway TRAFFICWAY W Arabia Steamboat 4TH Bridge CHARLOTTE 5TH 2ND ALNUT CHERRY S DELA MAIN Museum 35 HOLMES GILLIS LOCUST 5TH OAK DOWNTOWN COUNCIL HARRISON CAMPBELL W 1 GRAND MISSOURI 1 169 ARE Missouri River 3RD WYANDOTTE City Market PACIFIC 4TH WOODSWETHER RD MISSOURI 70 PACIFIC 5TH RIVER MARKET/COLUMBUS PARK INDEPENDENCE AVE. INDEPENDENCE AVE. 24 40 HIGHLAND Y 24 P MA P Comfort Inn 7TH and Suites 8TH ST ADMIRAL BLVD 7TH P BELLEVIEW P DOWNTOWN LOOP P BANKS WYANDOTTE GENESSEE 8TH 9TH ST P P P LYDIA P KC Central Library VIRGINIA 8TH 2 9TH WALNUT 2 LIBERTY P WYOMING P P FOREST NERO BLUFF TRACY Hotel 9TH BLVD Savoy MAIN JEFFERSON P BROADWAY 10TH CENTRAL P Lyric P Y HOLMES P TROOST DR ST. LOUIS AVE KIRK Theatre 10TH PASEO Quality Hill P P McGEE MARY LOU P GRAND CHARLOTTE WILLIAM LN UNION AVE P OAK P P P PENNSYLVANIA Playhouse P WASHINGTON 11TH BALTIMORE P 11TH LOCUST HICKORY WYANDOTTE CHERR MULBERRY SANTA FE THE 12TH Folly Theater KC Marriott P P 11TH P ELLA P Downtown Hotel Phillips P P FITZGERALD LN 12TH P 12TH ST. 13TH P P P P P 79 TROOST TRACY HARRISON FOREST Midland LYDIA Bartle Hall Aladdin P 12TH Holiday Inn Theatre by AMC P Municipal KC Repertory Theatre POWER & LIGHT DISTRICT Gates Bar-B-Q Auditorium, 13TH College Basketball Experience P E. 12TH TER 13TH ST Music Hall and Power & Light 13TH P Little Theatre Crowne District P P 3 P 3 14TH 670 Plaza 14THST P Hilton Sprint 14TH Convention Center VIRGINIA VINE LYDIA President Center P P P 14TH Main Street Theatre 14TH 70 HIGHLAND 16TH WYOMING GENESSEE LIBERTY TRUMAN ROAD JARBOE 16TH MAIN ST JACKSON COUNTY 16TH ST 16TH WEST SIDE Kauffman Center for 16TH ST the Performing Arts 17TH ST BEARDSLEY ROAD P 17TH BELLEVIEW 17TH 17TH P 17TH 18TH Y TIMORE WEST BOTTOMS ALNUT 18TH & VINE JAZZ DISTRICT AVE CAMPBELL W BAL GRAND 18TH McGEE TROOST LOCUST American Jazz Museum OAK Kemper CHERR HOLMES 4 CHARLOTTE 18TH & Negro Leagues 4 Arena 19TH MADISON ALLEN BELLEVIEW 18TH W. -

Appendix D – Historic Properties Survey Technical Report

Environmental Assessment Appendix D – Historic Properties Survey Technical Report Kansas City Streetcar Main Street Extension Project SECTION 106 TECHNICAL REPORT MO SHPO PROJECT NUMBER 211-JA-18 Prepared for the Federal Transit Administration By Architectural & Historical Research, LLC, Kansas City, MO January 21, 2019 This page left intentionally blank TABLE OF CONTENTS Project Background 2 Introduction 3 Streetcar Description 4 Methods and Area of Potential Effect 6 Disposition of Records 9 Results 10 Mass Transit in Kansas City and The Metropolitan Area 10 The Appropriateness of Placing Light Rail on Kansas City’s Boulevards 22 Architectural and Historical Contexts 24 Main Street Development 24 West Pershing to Thirty-First Streets 27 Thirty-First Street to Thirty-Ninth Street 31 Thirty-Ninth Street to Forty-Third Street 35 Forty-Third Street to Forty-Seventh Street 38 Forty-Seventh Street to Fifty-First Street 41 Inventory of Resources Within the APE 46 Determination of Effect 65 Recommended Mitigation 66 Bibliography 67 Appendices Kansas City Downtown Streetcar Project Page | i Section 106 Historic Resources Technical Report January 21, 2019 PROJECT BACKGROUND The Kansas City Downtown Streetcar starter line began service on May 6, 2016. The 2.2-mile line has provided more than 4.9 million trips in the 2+ years since opening day (over twice the projections). Due to overwhelming support and enthusiastic public interest in extending the streetcar route, the City of Kansas City, Missouri, the Kansas City Area Transportation Authority (KCATA), and the Kansas City Streetcar Authority (KCSA) have formed a Project Team to develop Federal Transit Administration (FTA) Section 5309 Capital Investment Grant Program – New Starts project justification materials and data in support of extending the streetcar approximately 3.5 miles south from its current terminus at West Pershing Road. -

Downtown Retail Directory

DOWNTOWN DIRECTORY LIVE, WORK, PLAY AND STAY IN KANSAS CITY 2018/2019 You’ll find a Unique Food Experience at You’ll find a Unique Food Experience at Downtown’s Award Winning Downtown’s Award Winning Cosentino’s! Open daily from 6 a.m. to 10Cosentino’s! p.m. Open daily from 6 a.m. to 10 p.m. Cosentino’s Market Cosentino’s10 East 13th Market Street MAIN ST. 10 East 13th Street 13TH ST. MAIN ST. Kansas City, Missouri 13TH ST. Kansas816-595-0055 City, Missouri 816-595-0055 Get Cosentino’s Market deliveredGet Cosentino’s in three Market easy steps! delivered in three easy steps! OVERLAND PARK OVERLAND8051 W 160TH ST, OVERLAND PARK,PARK KS 66223 GoGo to to CosentinosMarket.com CosentinosMarket.com toto ScheduleSchedule the delivery. the GetGet themthem delivereddelivered to order your groceries online. delivery or pickup. to your door. 8051 W 160TH ST, OVERLAND PARK, KS 66223 GoGoorder to to CosentinosMarket.com CosentinosMarket.com your groceries online. toto ScheduleSchedule the delivery. the GetGetyour themthem door delivereddelivered or pickup. to orderorder your your groceries groceries online.online.CosentinosMarket.comdelivery or pickup. yourto yourdoor door. or pickup. COSENTINOSMARKET.COM CosentinosMarket.com* Instacart account creation is required. COSENTINOSMARKET.COM 501006 * Instacart account creation is required. 501006Find us on Find us on FREE CHARMIN ESSENTIALSFREE GIANT ROLL 12 CT. CHARMIN ESSENTIALS GIANT ROLL 12 CT. VALID AT OVERLAND PARK LOCATION ONLY. WITH $25 PURCHASE VALID NOVEMBER 29 THROUGH DECEMBER 5, 2017 Limit one coupon per customer. No cash value. Excludes alcohol, tobacco, pharmacy or gift cards. VALID AT OVERLAND PARK LOCATION ONLY. -

Alternatives Analysis Auditorium Plaza Garage Kansas City, Missouri

850 West Jackson Boulevard, Suite 310 Chicago, IL 60607 312.633.4260 walkerconsultants.com August 20, 2019 Mr. Bruce Campbell Manager – ParkSmart KC City of Kansas City, Missouri City Hall, 414 E. 12th Street Kansas City, MO 64106 Re: Alternatives Analysis Auditorium Plaza Garage Kansas City, Missouri Dear Mr. Campbell: Walker Consultants (“Walker”) sincerely appreciates the opportunity to provide the accompanying parking alternatives analysis for the Auditorium Plaza Garage beneath Barney Allis Plaza in downtown Kansas City, Missouri. The City of Kansas City (“KCMO”) leadership, in support of continuous community improvement, wants to ensure public access to local destinations through strategic improvements and overall enhancements to the delivery of public parking services. KCMO engaged Walker to study site and area parking needs under current and future conditions and evaluate a few of the best ways to meet those needs. The following report provides an understanding the current parking needs in the immediate area, potential impacts of pending development, and how best to meet needs (as defined by KCMO priority). Groundwork from the proposed CBD Parking Study was used to provide insight into current and future supply and demand. This analysis was performed to speak specifically to the best way to balance parking needs once the Auditorium Plaza Garage is removed from service – replacing in-kind, partial replacement (balance of parking need accommodated nearby), or no replacement (entire parking need accommodated nearby). The alternatives analysis would consider quantitative and qualitative factors weighted by stakeholder input to inform recommendations. We look forward to engaging further with KCMO to provide excellent service and value-added insight from Walker’s years of experience in the parking industry. -

TEN Magazine

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF KANSAS CITY ANNUAL REPORT ISSUE ARBER B PHOTO BY GARY GARY BY PHOTO SPRING 2008 ANNUAL REPORT ISSUE BUILDING FOR THE FUTURE: Kansas City Fed moves into new headquarters………………………… ........ 28 The country’s newest Federal Reserve Bank building includes many connections to the past. The facility opens to the public July 1. FE ATURES RURAL SNAPSHOTS: A look back at 2007 gives a glimpse of 2008 ............................................................ 4 Ethanol and export demands as well as strong farm gains have been promising, but it’s rising production costs that will determine rural America’s prosperity this year. INDUSTRIAL LOAN COMPANIES: Commercial businesses face head-on opposition to entering the banking sector ........... 12 Current law leaves ILCs as the only option for businesses like Wal-Mart and Home Depot to open a bank, but this possibility causes uproar. REPAIRING THE DAMAGE: A combination of factors led to the nationwide foreclosure surge .................................. 20 The onslaught may continue through the next few years, but help is available for homeowners in distress. 2007 ANNUAL REPORT ...................................................... 37 Listings of officers, directors and advisory councils, and financial reports for the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. IN EVERY ISSUE 1 PRESIdent’s MESSAGE 32 ABOUT...CHECKS: THE END OF AN ERA 36 NOTES President’s message Moving forward, remembering the past he Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City us well and will remain an recently completed the move to our new important connection to headquarters at 1 Memorial Drive. For our history. T employees, this obviously has been a very There were, however, exciting, and historic, time. -

Annual Report 2006

The Francis Family Foundation Brighter futures for all generations... 2006 Introduction. Since 1913, when Parker Browne Francis II first launched the Oxygen Gas Company in Kansas City, Missouri, the Francis family has continued to be an inspirational and influential force in the Kansas City metropolitan area. In 1951, as the company grew and developed into a major national manufacturer and supplier of industrial and medical gases, Parker B. Francis II established a foundation bearing his name to help promote education and research in the fields of anesthesiology and related pulmonary sciences. Parker B. Francis III also established a foundation to fund his interests in education, and arts and culture. Since the two foundations merged in 1989 to become the Francis Family Foundation, the pattern of grantmaking made today still reflects the interests of the founding donors. For more information about the history of the Francis Family Foundation, please visit www.francisfoundation.org. Today, thanks to the vision of Parker B. Francis and his son John B. Francis, the Francis Family Foundation celebrates 56 years of philanthropy, including the funding of the Parker B. Francis Pulmonary Fellowship Program and support of educational and arts programs geographically located within the greater Kansas City metropolitan area. It is in the context of this history that our 2006 Annual Report honors the accomplishments of more than 180 grants representing a social investment of more than $6.4 million. While John B. Francis and his wife Mary Harris Francis are both deceased, stewardship of the Foundation was passed to their children – Ann F. Barhoum, David V.