28. Exterior Powers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

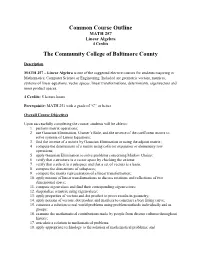

Common Course Outline MATH 257 Linear Algebra 4 Credits

Common Course Outline MATH 257 Linear Algebra 4 Credits The Community College of Baltimore County Description MATH 257 – Linear Algebra is one of the suggested elective courses for students majoring in Mathematics, Computer Science or Engineering. Included are geometric vectors, matrices, systems of linear equations, vector spaces, linear transformations, determinants, eigenvectors and inner product spaces. 4 Credits: 5 lecture hours Prerequisite: MATH 251 with a grade of “C” or better Overall Course Objectives Upon successfully completing the course, students will be able to: 1. perform matrix operations; 2. use Gaussian Elimination, Cramer’s Rule, and the inverse of the coefficient matrix to solve systems of Linear Equations; 3. find the inverse of a matrix by Gaussian Elimination or using the adjoint matrix; 4. compute the determinant of a matrix using cofactor expansion or elementary row operations; 5. apply Gaussian Elimination to solve problems concerning Markov Chains; 6. verify that a structure is a vector space by checking the axioms; 7. verify that a subset is a subspace and that a set of vectors is a basis; 8. compute the dimensions of subspaces; 9. compute the matrix representation of a linear transformation; 10. apply notions of linear transformations to discuss rotations and reflections of two dimensional space; 11. compute eigenvalues and find their corresponding eigenvectors; 12. diagonalize a matrix using eigenvalues; 13. apply properties of vectors and dot product to prove results in geometry; 14. apply notions of vectors, dot product and matrices to construct a best fitting curve; 15. construct a solution to real world problems using problem methods individually and in groups; 16. -

Equivalence of A-Approximate Continuity for Self-Adjoint

Equivalence of A-Approximate Continuity for Self-Adjoint Expansive Linear Maps a,1 b, ,2 Sz. Gy. R´ev´esz , A. San Antol´ın ∗ aA. R´enyi Institute of Mathematics, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest, P.O.B. 127, 1364 Hungary bDepartamento de Matem´aticas, Universidad Aut´onoma de Madrid, 28049 Madrid, Spain Abstract Let A : Rd Rd, d 1, be an expansive linear map. The notion of A-approximate −→ ≥ continuity was recently used to give a characterization of scaling functions in a multiresolution analysis (MRA). The definition of A-approximate continuity at a point x – or, equivalently, the definition of the family of sets having x as point of A-density – depend on the expansive linear map A. The aim of the present paper is to characterize those self-adjoint expansive linear maps A , A : Rd Rd for which 1 2 → the respective concepts of Aµ-approximate continuity (µ = 1, 2) coincide. These we apply to analyze the equivalence among dilation matrices for a construction of systems of MRA. In particular, we give a full description for the equivalence class of the dyadic dilation matrix among all self-adjoint expansive maps. If the so-called “four exponentials conjecture” of algebraic number theory holds true, then a similar full description follows even for general self-adjoint expansive linear maps, too. arXiv:math/0703349v2 [math.CA] 7 Sep 2007 Key words: A-approximate continuity, multiresolution analysis, point of A-density, self-adjoint expansive linear map. 1 Supported in part in the framework of the Hungarian-Spanish Scientific and Technological Governmental Cooperation, Project # E-38/04. -

Introduction to Linear Bialgebra

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of New Mexico University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Mathematics and Statistics Faculty and Staff Publications Academic Department Resources 2005 INTRODUCTION TO LINEAR BIALGEBRA Florentin Smarandache University of New Mexico, [email protected] W.B. Vasantha Kandasamy K. Ilanthenral Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/math_fsp Part of the Algebra Commons, Analysis Commons, Discrete Mathematics and Combinatorics Commons, and the Other Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Smarandache, Florentin; W.B. Vasantha Kandasamy; and K. Ilanthenral. "INTRODUCTION TO LINEAR BIALGEBRA." (2005). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/math_fsp/232 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Department Resources at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mathematics and Statistics Faculty and Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. INTRODUCTION TO LINEAR BIALGEBRA W. B. Vasantha Kandasamy Department of Mathematics Indian Institute of Technology, Madras Chennai – 600036, India e-mail: [email protected] web: http://mat.iitm.ac.in/~wbv Florentin Smarandache Department of Mathematics University of New Mexico Gallup, NM 87301, USA e-mail: [email protected] K. Ilanthenral Editor, Maths Tiger, Quarterly Journal Flat No.11, Mayura Park, 16, Kazhikundram Main Road, Tharamani, Chennai – 600 113, India e-mail: [email protected] HEXIS Phoenix, Arizona 2005 1 This book can be ordered in a paper bound reprint from: Books on Demand ProQuest Information & Learning (University of Microfilm International) 300 N. -

LECTURES on PURE SPINORS and MOMENT MAPS Contents 1

LECTURES ON PURE SPINORS AND MOMENT MAPS E. MEINRENKEN Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Volume forms on conjugacy classes 1 3. Clifford algebras and spinors 3 4. Linear Dirac geometry 8 5. The Cartan-Dirac structure 11 6. Dirac structures 13 7. Group-valued moment maps 16 References 20 1. Introduction This article is an expanded version of notes for my lectures at the summer school on `Poisson geometry in mathematics and physics' at Keio University, Yokohama, June 5{9 2006. The plan of these lectures was to give an elementary introduction to the theory of Dirac structures, with applications to Lie group valued moment maps. Special emphasis was given to the pure spinor approach to Dirac structures, developed in Alekseev-Xu [7] and Gualtieri [20]. (See [11, 12, 16] for the more standard approach.) The connection to moment maps was made in the work of Bursztyn-Crainic [10]. Parts of these lecture notes are based on a forthcoming joint paper [1] with Anton Alekseev and Henrique Bursztyn. I would like to thank the organizers of the school, Yoshi Maeda and Guiseppe Dito, for the opportunity to deliver these lectures, and for a greatly enjoyable meeting. I also thank Yvette Kosmann-Schwarzbach and the referee for a number of helpful comments. 2. Volume forms on conjugacy classes We will begin with the following FACT, which at first sight may seem quite unrelated to the theme of these lectures: FACT. Let G be a simply connected semi-simple real Lie group. Then every conjugacy class in G carries a canonical invariant volume form. -

21. Orthonormal Bases

21. Orthonormal Bases The canonical/standard basis 011 001 001 B C B C B C B0C B1C B0C e1 = B.C ; e2 = B.C ; : : : ; en = B.C B.C B.C B.C @.A @.A @.A 0 0 1 has many useful properties. • Each of the standard basis vectors has unit length: q p T jjeijj = ei ei = ei ei = 1: • The standard basis vectors are orthogonal (in other words, at right angles or perpendicular). T ei ej = ei ej = 0 when i 6= j This is summarized by ( 1 i = j eT e = δ = ; i j ij 0 i 6= j where δij is the Kronecker delta. Notice that the Kronecker delta gives the entries of the identity matrix. Given column vectors v and w, we have seen that the dot product v w is the same as the matrix multiplication vT w. This is the inner product on n T R . We can also form the outer product vw , which gives a square matrix. 1 The outer product on the standard basis vectors is interesting. Set T Π1 = e1e1 011 B C B0C = B.C 1 0 ::: 0 B.C @.A 0 01 0 ::: 01 B C B0 0 ::: 0C = B. .C B. .C @. .A 0 0 ::: 0 . T Πn = enen 001 B C B0C = B.C 0 0 ::: 1 B.C @.A 1 00 0 ::: 01 B C B0 0 ::: 0C = B. .C B. .C @. .A 0 0 ::: 1 In short, Πi is the diagonal square matrix with a 1 in the ith diagonal position and zeros everywhere else. -

NOTES on DIFFERENTIAL FORMS. PART 3: TENSORS 1. What Is A

NOTES ON DIFFERENTIAL FORMS. PART 3: TENSORS 1. What is a tensor? 1 n Let V be a finite-dimensional vector space. It could be R , it could be the tangent space to a manifold at a point, or it could just be an abstract vector space. A k-tensor is a map T : V × · · · × V ! R 2 (where there are k factors of V ) that is linear in each factor. That is, for fixed ~v2; : : : ;~vk, T (~v1;~v2; : : : ;~vk−1;~vk) is a linear function of ~v1, and for fixed ~v1;~v3; : : : ;~vk, T (~v1; : : : ;~vk) is a k ∗ linear function of ~v2, and so on. The space of k-tensors on V is denoted T (V ). Examples: n • If V = R , then the inner product P (~v; ~w) = ~v · ~w is a 2-tensor. For fixed ~v it's linear in ~w, and for fixed ~w it's linear in ~v. n • If V = R , D(~v1; : : : ;~vn) = det ~v1 ··· ~vn is an n-tensor. n • If V = R , T hree(~v) = \the 3rd entry of ~v" is a 1-tensor. • A 0-tensor is just a number. It requires no inputs at all to generate an output. Note that the definition of tensor says nothing about how things behave when you rotate vectors or permute their order. The inner product P stays the same when you swap the two vectors, but the determinant D changes sign when you swap two vectors. Both are tensors. For a 1-tensor like T hree, permuting the order of entries doesn't even make sense! ~ ~ Let fb1;:::; bng be a basis for V . -

What's in a Name? the Matrix As an Introduction to Mathematics

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences Faculty/Staff Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences 9-2008 What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Kris H. Green St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub Part of the Mathematics Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Publication Information Green, Kris H. (2008). "What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics." Math Horizons 16.1, 18-21. Please note that the Publication Information provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub/12 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Abstract In lieu of an abstract, here is the article's first paragraph: In my classes on the nature of scientific thought, I have often used the movie The Matrix to illustrate the nature of evidence and how it shapes the reality we perceive (or think we perceive). As a mathematician, I usually field questions elatedr to the movie whenever the subject of linear algebra arises, since this field is the study of matrices and their properties. So it is natural to ask, why does the movie title reference a mathematical object? Disciplines Mathematics Comments Article copyright 2008 by Math Horizons. -

Multivector Differentiation and Linear Algebra 0.5Cm 17Th Santaló

Multivector differentiation and Linear Algebra 17th Santalo´ Summer School 2016, Santander Joan Lasenby Signal Processing Group, Engineering Department, Cambridge, UK and Trinity College Cambridge [email protected], www-sigproc.eng.cam.ac.uk/ s jl 23 August 2016 1 / 78 Examples of differentiation wrt multivectors. Linear Algebra: matrices and tensors as linear functions mapping between elements of the algebra. Functional Differentiation: very briefly... Summary Overview The Multivector Derivative. 2 / 78 Linear Algebra: matrices and tensors as linear functions mapping between elements of the algebra. Functional Differentiation: very briefly... Summary Overview The Multivector Derivative. Examples of differentiation wrt multivectors. 3 / 78 Functional Differentiation: very briefly... Summary Overview The Multivector Derivative. Examples of differentiation wrt multivectors. Linear Algebra: matrices and tensors as linear functions mapping between elements of the algebra. 4 / 78 Summary Overview The Multivector Derivative. Examples of differentiation wrt multivectors. Linear Algebra: matrices and tensors as linear functions mapping between elements of the algebra. Functional Differentiation: very briefly... 5 / 78 Overview The Multivector Derivative. Examples of differentiation wrt multivectors. Linear Algebra: matrices and tensors as linear functions mapping between elements of the algebra. Functional Differentiation: very briefly... Summary 6 / 78 We now want to generalise this idea to enable us to find the derivative of F(X), in the A ‘direction’ – where X is a general mixed grade multivector (so F(X) is a general multivector valued function of X). Let us use ∗ to denote taking the scalar part, ie P ∗ Q ≡ hPQi. Then, provided A has same grades as X, it makes sense to define: F(X + tA) − F(X) A ∗ ¶XF(X) = lim t!0 t The Multivector Derivative Recall our definition of the directional derivative in the a direction F(x + ea) − F(x) a·r F(x) = lim e!0 e 7 / 78 Let us use ∗ to denote taking the scalar part, ie P ∗ Q ≡ hPQi. -

Tensor Products

Tensor products Joel Kamnitzer April 5, 2011 1 The definition Let V, W, X be three vector spaces. A bilinear map from V × W to X is a function H : V × W → X such that H(av1 + v2, w) = aH(v1, w) + H(v2, w) for v1,v2 ∈ V, w ∈ W, a ∈ F H(v, aw1 + w2) = aH(v, w1) + H(v, w2) for v ∈ V, w1, w2 ∈ W, a ∈ F Let V and W be vector spaces. A tensor product of V and W is a vector space V ⊗ W along with a bilinear map φ : V × W → V ⊗ W , such that for every vector space X and every bilinear map H : V × W → X, there exists a unique linear map T : V ⊗ W → X such that H = T ◦ φ. In other words, giving a linear map from V ⊗ W to X is the same thing as giving a bilinear map from V × W to X. If V ⊗ W is a tensor product, then we write v ⊗ w := φ(v ⊗ w). Note that there are two pieces of data in a tensor product: a vector space V ⊗ W and a bilinear map φ : V × W → V ⊗ W . Here are the main results about tensor products summarized in one theorem. Theorem 1.1. (i) Any two tensor products of V, W are isomorphic. (ii) V, W has a tensor product. (iii) If v1,...,vn is a basis for V and w1,...,wm is a basis for W , then {vi ⊗ wj }1≤i≤n,1≤j≤m is a basis for V ⊗ W . -

Handout 9 More Matrix Properties; the Transpose

Handout 9 More matrix properties; the transpose Square matrix properties These properties only apply to a square matrix, i.e. n £ n. ² The leading diagonal is the diagonal line consisting of the entries a11, a22, a33, . ann. ² A diagonal matrix has zeros everywhere except the leading diagonal. ² The identity matrix I has zeros o® the leading diagonal, and 1 for each entry on the diagonal. It is a special case of a diagonal matrix, and A I = I A = A for any n £ n matrix A. ² An upper triangular matrix has all its non-zero entries on or above the leading diagonal. ² A lower triangular matrix has all its non-zero entries on or below the leading diagonal. ² A symmetric matrix has the same entries below and above the diagonal: aij = aji for any values of i and j between 1 and n. ² An antisymmetric or skew-symmetric matrix has the opposite entries below and above the diagonal: aij = ¡aji for any values of i and j between 1 and n. This automatically means the digaonal entries must all be zero. Transpose To transpose a matrix, we reect it across the line given by the leading diagonal a11, a22 etc. In general the result is a di®erent shape to the original matrix: a11 a21 a11 a12 a13 > > A = A = 0 a12 a22 1 [A ]ij = A : µ a21 a22 a23 ¶ ji a13 a23 @ A > ² If A is m £ n then A is n £ m. > ² The transpose of a symmetric matrix is itself: A = A (recalling that only square matrices can be symmetric). -

Multilinear Algebra and Applications July 15, 2014

Multilinear Algebra and Applications July 15, 2014. Contents Chapter 1. Introduction 1 Chapter 2. Review of Linear Algebra 5 2.1. Vector Spaces and Subspaces 5 2.2. Bases 7 2.3. The Einstein convention 10 2.3.1. Change of bases, revisited 12 2.3.2. The Kronecker delta symbol 13 2.4. Linear Transformations 14 2.4.1. Similar matrices 18 2.5. Eigenbases 19 Chapter 3. Multilinear Forms 23 3.1. Linear Forms 23 3.1.1. Definition, Examples, Dual and Dual Basis 23 3.1.2. Transformation of Linear Forms under a Change of Basis 26 3.2. Bilinear Forms 30 3.2.1. Definition, Examples and Basis 30 3.2.2. Tensor product of two linear forms on V 32 3.2.3. Transformation of Bilinear Forms under a Change of Basis 33 3.3. Multilinear forms 34 3.4. Examples 35 3.4.1. A Bilinear Form 35 3.4.2. A Trilinear Form 36 3.5. Basic Operation on Multilinear Forms 37 Chapter 4. Inner Products 39 4.1. Definitions and First Properties 39 4.1.1. Correspondence Between Inner Products and Symmetric Positive Definite Matrices 40 4.1.1.1. From Inner Products to Symmetric Positive Definite Matrices 42 4.1.1.2. From Symmetric Positive Definite Matrices to Inner Products 42 4.1.2. Orthonormal Basis 42 4.2. Reciprocal Basis 46 4.2.1. Properties of Reciprocal Bases 48 4.2.2. Change of basis from a basis to its reciprocal basis g 50 B B III IV CONTENTS 4.2.3. -

Bases for Infinite Dimensional Vector Spaces Math 513 Linear Algebra Supplement

BASES FOR INFINITE DIMENSIONAL VECTOR SPACES MATH 513 LINEAR ALGEBRA SUPPLEMENT Professor Karen E. Smith We have proven that every finitely generated vector space has a basis. But what about vector spaces that are not finitely generated, such as the space of all continuous real valued functions on the interval [0; 1]? Does such a vector space have a basis? By definition, a basis for a vector space V is a linearly independent set which generates V . But we must be careful what we mean by linear combinations from an infinite set of vectors. The definition of a vector space gives us a rule for adding two vectors, but not for adding together infinitely many vectors. By successive additions, such as (v1 + v2) + v3, it makes sense to add any finite set of vectors, but in general, there is no way to ascribe meaning to an infinite sum of vectors in a vector space. Therefore, when we say that a vector space V is generated by or spanned by an infinite set of vectors fv1; v2;::: g, we mean that each vector v in V is a finite linear combination λi1 vi1 + ··· + λin vin of the vi's. Likewise, an infinite set of vectors fv1; v2;::: g is said to be linearly independent if the only finite linear combination of the vi's that is zero is the trivial linear combination. So a set fv1; v2; v3;:::; g is a basis for V if and only if every element of V can be be written in a unique way as a finite linear combination of elements from the set.