DFAT COUNTRY INFORMATION REPORT LEBANON 23 October 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protesters Attack US Embassy in Baghdad Over Deadly Air Strikes US to Send Marines to Embassy As Trump Blames Iran

JUMADA ALAWWAL 6, 1441 AH WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 1, 2020 28 Pages Max 19º Min 11º 150 Fils Established 1961 ISSUE NO: 18025 The First Daily in the Arabian Gulf www.kuwaittimes.net Don’t miss your copy Protesters attack US embassy in Baghdad over deadly air strikes US to send Marines to embassy as Trump blames Iran BAGHDAD: Iraqi supporters of pro-Iran factions attacked the US embassy in Baghdad yesterday, breach- NOTICE ing its outer wall and chanting “Death to America!” in anger over weekend air strikes that killed two dozen fight- Happy New Year to all our readers! Kuwait ers. It was the first time in years protesters have been able Times will not be published on Thursday, to reach the US embassy, which is sheltered behind a January 2, 2020 and Friday, January 3. Our series of checkpoints in the high-security Green Zone. A next issue will hit the newsstands on stream of men in military fatigues, as well as some women, Sunday, January 5. However, readers can marched through those checkpoints to the embassy walls stay updated on breaking news and events with no apparent reaction from Iraqi security forces. on our digital media channels including our US President Donald Trump in a Twitter message website www.kuwaittimes.net and on accused Iran of “orchestrating” the attack and said it “will Instagram, Twitter and Facebook. be held fully responsible”, but he also said he expected Iraq “to use its forces to protect the embassy”. The Washington Post reported that inside the embassy, US diplomats and staffers were huddled in a fortified safe room, according to two reached by a messaging app. -

Lebanon Flash Appeal

FLASH 2020 APPEAL AUGUST LEBANON Photo: Agency/Photographer Financial Requirements (US$) People Targeted $565M 300,000 Beirut, Lebanon: Buildings Exposure to the Explosions with Damaged Hospitals and Health Facilities (as of 12 August 2020) Mediterranean sea Blast Location Damaged Health Centers BEIRUT Completely out of order Hospital MOUNT LEBANON Partially out of order Hospital Buildings Exposure to Blast Low High BEIRUT The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. This document is produced by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) in collaboration with humanitarian partners in support of national efforts. It covers the period from mid August to November 2020 and is issued on 14 August 2020. Cover photo by Marwan Naamani/picture alliance via Getty Images The designations employed and the presentation of material on this report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. PART 1: CRISIS OVERVIEW 300,000 LEBANON CRISIS OVERVIEW The Beirut Port explosions on 4 August created The first phase will prioritize life-saving responses significant immediate humanitarian needs and severe and protection. These activities continue alongside long-term consequences. the pre-existing humanitarian response for the Leba- nese and non-Lebanese population, including Syrian Building on existing humanitarian response efforts, a and Palestine refugees and migrants. comprehensive, effective response to this emergency requires three phases of activity. -

Environmental Governance, Beirut, Lebanon

European Union – ENPI/2014/337-755 Support to Reforms – Environmental Governance, Beirut, Lebanon Project Identification No. EuropeAid/134306/D/SER/LB/3 Service Contract No: ENPI/2014/337-755 Assessment of Solid Waste Management Practices in Lebanon in 2015 First report date: December 2016 Final report date: September 2017 A project implemented by GFA Consulting Group GmbH / Umweltbundesamt / Mott Mac Donald This project is funded by the European Union Your contact person within GFA Consulting Group GmbH is Constanze Schaaff (Project Director) Lebanon Support to Reforms – Environmental Governance, Beirut, Lebanon EuropeAid/134306/D/SER/LB/3 Assessment of Solid Waste Management Practices in Lebanon in 2015 Overall preparation of the report: Lamia Mansour, Policy Expert, StREG Programme Manal Moussallem, Senior Environmental Advisor, UNDP/MoE Ahmad Osman, Policy Analyst, StREG Programme Preparation of Solid Waste Management Scenarios for the SEA: Costis Nicolopoulos: SEA Expert (Head of Environmental Unit, LDK Consultants) Siegmund Böhmer: Waste to Energy (WtE) Expert (Head of Department, Air Pollution Control, Buildings & Registries, Umweltbundesamt GmbH, Austria) Brigitte Karigl: Solid Waste Data Management Expert (Waste & Material Flow Management, Umweltbundesamt GmbH, Austria) Mazen Makki: Environmental Expert (Independent Consultant) Naji Abou Assaly: Institutional Expert (Independent Consultant) Address: GFA Consulting Group GmbH Eulenkrugstraße 82 D-22359 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (40) 6 03 06 – 174 Fax: +49 (40) 6 03 06 – 179 E-Mail: -

The Labour Market in Lebanon, Statistics in Focus (SIF), Central Administration of Statistics, Lebanon, Issue Number 1, October 2011

We are here to help you! Should you require any help or assistance about this publication, please email us at [email protected] Or give us a call at +9611 373 164 You can also visit our website www.cas.gov.lb where you can download free available statistics and indicators about Lebanon. Suggested Citation: The labour market in Lebanon, Statistics In Focus (SIF), Central Administration of Statistics, Lebanon, Issue number 1, October 2011. This publication is free of charge and can be found at the following link: http://www. cas.gov.lb/index.php?option=com_conte nt&view=article&id=58&Itemid=40 Designed by: Khodor Daher – Central Administration of Statistics, Lebanon This publication was prepared within the EU Twining project to support the Central Administration of Statistics in Lebanon Within the context of the EU Twining Project between the Central Administration of Statistics (CAS) Lebanon and the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA) Northern Ireland- UK, CAS has the pleasure making available to user the first issue of the Statistics In Focus (SIF), a series of publications on Social Statistics, entitled ‘The Labour Market in Lebanon’. This issue of the SIF contains key indicators and figures on the Labour Market in Lebanon; it is based on official statistics and can be considered as a reference for users who are looking for general statistics and information about the topic. The Central Administration of Statistics wishes to thank the persons who contributed to this publication. Dr. MARAL TUTELIAN GUIDANIAN Director General Central Administration of Statistics The Labour market in Lebanon The Central Administration of Statistics important information on the Lebanese (CAS) in Lebanon is launching «Statistics labour market enabling them to understand In Focus» (SIF), a series of publications on the current situation and to compare Lebanon several social and economic indicators about to neighbouring countries. -

Digital Identity

Digital Identity APPENDIX B: Case Studies Citing reference: FATF (2020), “Appendix B” in Guidance on Digital Identity, FATF, Paris, www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/documents/digital-identity-guidance.html For more information about the FATF, please visit www.fatf-gafi.org This document and/or any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. © 2020 FATF/OECD. All rights reserved. No reproduction or translation of this publication may be made without prior written permission. Applications for such permission, for all or part of this publication, should be made to the FATF Secretariat, 2 rue André Pascal 75775 Paris Cedex 16, France (fax: +33 1 44 30 61 37 or e-mail: [email protected]) Photocredits coverphoto ©Getty Images GUIDANCE ON DIGITAL IDENTITY | 71 APPENDIX B: CASE STUDIES Box 4. India’s Unique ID (UID) number Features of the digital ID system: India’s Unique ID (UID) number—or Aadhaar— identity program uses multiple biometrics and biographic information, as well as official identity documentation where it is available, to provide a digital ID to all residents in India, regardless of age or nationality. The Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) has released a mobile app, m- Aadhaar, which generates a “virtual ID” number, linked to but different than the Aadhaar number, to increase privacy and security. Both the Aadhaar number and Virtual ID can be authenticated online, against the Aadhaar database, or offline, using a QR code. -

Syria Refugee Response

SYRIA REFUGEE RESPONSE Distribution of MoPH network and UNHCR Health Brochure Selected PHC as of 6 October, 2016 Akkar Governorate, Akkar District - Number of syrian refugees : 99,048 Legend !( Moph Network Moph Network !< and UNHCR Dayret Nahr Health El-Kabir 1,439 Brochure ") UNHCR Health Brochure Machta Hammoud Non under 2,246 MoPH network 30221 ! or under 30123 35516_31_001 35249_31_001 IMC No partner Wadi Khaled health center UNHCR Health Al Aaboudiyeh Governmental center !< AAridet Sammaqiye !( 713 Aaouaainat Khalsa Brochure Cheikh Hokr Hokr Dibbabiye Aakkar 1 30216 Zennad Jouret Janine Ed-Dahri 67 Kfar 6 35512_31_001 6 Srar 13 !( Aamayer Kharnoubet Noun No partner 13,361 Barcha Khirbet Er Aakkar 8 Alaaransa charity center Most Vulnerable Massaaoudiye 7 Aarme Mounjez Remmane 386 Noura ! 29 25 13 Qachlaq Et-Tahta 35512-40-01 Localities Tall Chir 28 17 Hmayra No partner Cheikh Kneisset Hmairine Aamaret Fraydes ! 105 1,317 Srar Aakkar Cheikhlar Wadi Khaled SDC Qarha Zennad Aakkar Tall El-Baykat 108 7 Rmah 62 Aandqet !< Aakkar 257 Mighraq 33 Bire 462 Most Mzeihme Ouadi 49 401 17 44 Aakkar 11 El-Haour Kouachra 168 Baghdadi Vulnerable Haytla 636 1,780 Qsair Hnaider 30226 !( Darine 10 Aamriyet Aakkar 1,002 35229_31_001 124 Aakkar 35 Mazraat 2nd Most No partner Tall Aabbas Saadine Alkaram charity center - Massoudieh Ech-Charqi 566 En-Nahriye Kneisset Tleil Barde 958 878 Hnaider Vulnerable !< 798 35416-40-01 4 Ghazayle 1,502 30122 38 No partner ! 35231_31_001 Bire Qleiaat Aain Ez-Zeit Kafr Khirbet ")!( IMC Aain 3rd Most Aakkar Hayssa Saidnaya -

Inception Report

Inception Report Regular Perception Surveys on Social Tensions throughout Lebanon: Wave I April 2017 Contents 1 Sampling Summary 1 1.1 First and Second Stage Sampling . .1 1.2 Third and Fourth Stage Sampling . .2 1.3 Enumerator Recruitment and Training . .3 2 The Questionnaire: Analysis Plan 4 2.1 Structural Causes . .6 2.2 Evolving Causes . .6 2.3 Proximate Causes . .7 2.4 Trigger Events . .9 2.5 Demographics . 10 Appendix A Distribution of Interviews 11 Appendix B Maps 14 Appendix C Survey Instrument 17 i 1. Sampling Summary This inception report summarizes the first and second stages of selection in the sampling process and includes a draft survey instrument. The proposed distribution of interviews across governorates, districts and vulnerability-levels are given in Appendix A: Distribution of Interviews. The distribution of Lebanon’s population, vulnerability-levels, and the proposed allocation of interviews at the cadaster level is visualized in Appendix B: Maps. The proposed survey instrument is available in English at https://enketo.ona.io/x/#YTxI and also included in Appendix C: Survey Instrument. 1.1. First and Second Stage Sampling Given the research objectives of the survey and with the proposed sample size of N = 5; 000 interviews per survey wave, there will be adequate statistical power to assess meaningful differences in outcomes with precision at the governorate (muhafaza) level, as well as differences across levels of vulnerability indicated in the ‘Most Vulnerable Localities in Lebanon’ map (see Map B.2). A complex sample design was required to optimize the efficiency of the sample across the two dimensions of (a) district geographies and (b) vulnerability-level geographies, while at the same time (c) minimizing the margin of error for total-sample statistics. -

Women's Citizenship Rights in Lebanon

Research, Advocacy & Public Policy-Making Women’s Citizenship Rights in Lebanon May 2012 May Maya W. Mansour Beirut Bar Association; Lecturer in Human Rights at Beirut Arab University Sarah G. Abou Aad Beirut Bar Association; Human Rights in Lebanon Researcher and Activisit Working Paper Series #8 Paper Working Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs American University of Beirut Research, Advocacy & Public Policy-Making Working Paper Series #8 | May 2012 Women’s Citizenship Rights in Lebanon Research, Advocacy and Public Policy-making in the Arab World (RAPP) studies the effectiveness of think tanks and research policy institutes in influencing public policy in the region. It aims to establish a permanent network of self-financed think tanks and research centers across the Middle East that are better able to impact public policy in their respective countries. Rami G. Khouri IFI Director Dr. Karim Makdisi IFI Associate Director Rayan El-Amine Programs Manager Maya W. Mansour Dr. Hana G. El-Ghali Senior Program Coordinator Beirut Bar Association; Lecturer in Human Rights at Beirut Arab University Hania Bekdash Program Coordinator Zaki Boulos Communications Manager Sarah G. Abou Aad Donna Rajeh Designer Beirut Bar Association; Human Rights in Lebanon Researcher and Activisit This research project is funded by Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs (IFI) at the American University of Beirut (AUB). The views expressed in this document are solely those of the authors, and do not reflect the views of the Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs or the American University of Beirut. Beirut, March 2012 © All rights reserved Principal Investigators: Maya W. -

Imam Musa Al-Sadr: an Analysis of His Life, Accomplishments and Literary Output

Imam Musa al-Sadr: An analysis of his life, accomplishments and literary output Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Naim, Ibrahim Ali, 1962- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 02:35:09 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/282708 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper aligiunent can adversely afifect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. -

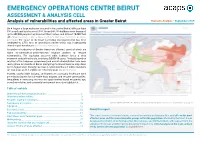

EMERGENCY OPERATIONS CENTRE BEIRUT ASSESSMENT & ANALYSIS CELL Analysis of Vulnerabilities and Affected Areas in Greater Beirut Thematic Analysis - September 2020

EMERGENCY OPERATIONS CENTRE BEIRUT ASSESSMENT & ANALYSIS CELL Analysis of vulnerabilities and affected areas in Greater Beirut Thematic Analysis - September 2020 On 4 August a large explosion occurred in the port of Beirut, killing at least 191 people and injuring over 6,500. Around 40,000 buildings were damaged, up to 300,000 people may have lost their homes, and at least 70,000 their job (OCHA 25/08/2020, UNDP in OCHA 17/08/2020, BBC News 15/09/2020, Al Jazeera 24/08/2020). The cause of the blast is pending investigation but has been attributed to 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate which was inadequately stored in port warehouses (The Guardian 05/08/2020). A number of cadastres of Greater Beirut are affected, some of which are home to vulnerable or poor Lebanese, migrant workers or refugee communities. The explosion occurred while Lebanon faces a deep economic and political crisis, and rising COVID-19 cases. Protests based on mistrust of the Lebanese government and overall administration have been taking place for months in Beirut prompting the Government to step down on 10 August 2020. Poverty has risen in recent months; 2.7 million residents are now poor and 1.1. million are extremely poor (ESCWA 19/08/2020). Poverty, unaffordable housing, and barriers to accessing healthcare were pre-existing issues for vulnerable host, migrant, and refugee communities. Inequalities in accessing services and opportunities based on gender, age, sexual orientation, and a minority background were also highlighted. Table of contents Overview and humanitarian situation…………………………………………….……….... 2 Underlying vulnerabilities………………..………………………………………….……..….……. 3 Negative coping mechanisms..…………………..…………..………………..……..…….. -

Narrative Report

Narrative Report Regular Perception Surveys on Social Tensions throughout Lebanon: Wave I July 2017 PROTECT Regular Perception Surveys on Social Tensions throughout Lebanon Wave I: Narrative Report August 2017 Beirut, Lebanon This report was prepared by ARK Group DMCC (www.arkgroupdmcc.com) on behalf of the UNDP in Lebanon, with funding from the Dutch government. The authors’ views in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of UNDP, other UN agencies, the Social Stability Working Group or the Dutch government. PROTECT Executive Summary To better unpack inter-community tensions in Lebanon in the context of the current crisis and trace them over time, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), as the lead agency of the stabilisation dimension of the Lebanon Crisis Response Plan (LCRP), commissioned ARK to conduct four nationally representative surveys over a period of one year in Lebanon. This report, funded by the Dutch Government, summarizes the findings of the first wave of surveying, with fieldwork taking place between 26 April 2017 and 29 May 2017. The following section outlines the key social stability trends emerging from the survey results and makes tentative recommendations for LCRP programming to strengthen community resilience and stability in Lebanon. Tensions remain prevalent but stable, with competition in the labour market a primary concern for Lebanese in all Governorates. The survey reveals multiple layers of tensions between communities, with high social distance between communities. While nearly half of Syrians would consider inter-community relations positive, only 28% of Lebanese do so. While only 10% of Lebanese would characterize relations as ‘very negative’ and a majority would consider the level of tension stable, only two percent of respondents say that there is ‘not tension’ in their area. -

Consociationalism and State-Society Relations in Lebanon Norma

Consociationalism and State-Society Relations in Lebanon Norma Roumie A Thesis Submitted to the School of International Development and Global Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the M.A. in International Development and Globalization School of International Development and Global Studies of Faculty of Social Sciences University of Ottawa © Norma Roumie, Ottawa, Canada, 2020 ii Table of Contents Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... iii Acknowledgement/Preface: ........................................................................................................... iv CHAPTER 1 - Introduction and Literature Review ........................................................................1 Literature Review - Divided Societies and Power-sharing .....................................4 State-society Relations ...........................................................8 Conceptual/Theoretical Framework......................................................................15 Research Questions ...............................................................................................16 Methodology .........................................................................................................17 Ethics.....................................................................................................................23 CHAPTER 2 - Context - the History of Modern Lebanon ............................................................26