Restoring Localism to Broadcast Communications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Carolina Emergency Alert System State Plan

North Carolina Emergency Alert System State Plan August 2011 Table of Contents Overview ................................................................................................................................ 3 Authority ................................................................................................................................ 3 Participation in and Priorities of the Emergency Alert System… ......................................... 4 Participation in the National System ......................................................................... 4 Participation in the State and Local System .............................................................. 4 Emergency Alert System Priorities ........................................................................... 6 Activation Procedures for the Emergency Alert System ....................................................... 7 National Activation Procedures ................................................................................. 7 State Activation Procedures ....................................................................................... 7 Local Activation Procedures ...................................................................................... 7 North Carolina Child Abduction Activation Procedures .......................................... 8 Weather-Related Activation Procedures .................................................................... 8 Origins of Emergency Alert System Messages .................................................................... -

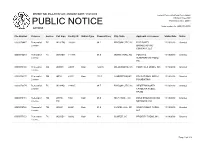

Public Notice >> Licensing and Management System Admin >>

REPORT NO. PN-1-190805-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 08/05/2019 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 APPLICATIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000079563 Renewal of AM WREV 41442 Main 1220.0 REIDSVILLE, NC Rodriguez, Estuardo 08/01/2019 Accepted License Valdemar and For Filing Rodriguez, Leonor 0000079594 Renewal of FX W237CM 145202 95.3 FAYETTEVILLE, Educational 08/01/2019 Accepted License NC Information For Filing Corporation 0000079809 Renewal of AM WIAM 37450 Main 900.0 WILLIAMSTON, NC LIFELINE 08/01/2019 Accepted License MINISTRIES, INC For Filing 0000079721 Renewal of AM WCOG 74203 Main 1320.0 GREENSBORO, NC CRESCENT MEDIA 08/01/2019 Accepted License GROUP LLC For Filing 0000079744 Renewal of FM WWMY 22224 Main 102.3 BEECH MOUNTAIN HIGH COUNTRY 08/01/2019 Accepted License , NC ADVENTURES, LLC For Filing 0000079718 Renewal of AM WMFR 73257 Main 1230.0 HIGH POINT, NC CRESCENT MEDIA 08/01/2019 Accepted License GROUP LLC For Filing 0000079789 Renewal of AM WOBX 73367 Main 1530.0 WANCHESE, NC EAST CAROLINA 08/01/2019 Accepted License RADIO, INC. For Filing 0000079579 Renewal of FL WFOZ- 194129 105.1 WINSTON-SALEM, FORSYTH 08/01/2019 Accepted License LP NC TECHNICAL For Filing COMMUNITY COLLEGE Page 1 of 27 REPORT NO. PN-1-190805-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 08/05/2019 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. -

The Magazine for TV and FM Dxers

The Official Publication of the Worldwide TV-FM DX Association DECEMBER 2004 The Magazine for TV and FM DXers TV and FM DXing was never so much Fun! IN THIS ISSUE MAPPING THE JULY 6TH Es CLOUD BOB COOPER’S ARTICLE ON COLOR TV CONTINUES THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION Serving the UHF-VHF Enthusiast THE VHF-UHF DIGEST IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION DEDICATED TO THE OBSERVATION AND STUDY OF THE PROPAGATION OF LONG DISTANCE TELEVISION AND FM BROADCASTING SIGNALS AT VHF AND UHF. WTFDA IS GOVERNED BY A BOARD OF DIRECTORS: DOUG SMITH, GREG CONIGLIO, BRUCE HALL, DAVE JANOWIAK AND MIKE BUGAJ. Editor and publisher: Mike Bugaj Treasurer: Dave Janowiak Webmaster: Tim McVey Editorial Staff:, Victor Frank, George W. Jensen, Jeff Kruszka Keith McGinnis, Fred Nordquist, Matt Sittel, Doug Smith, Adam Rivers and John Zondlo, Our website: www.anarc.org/wtfda ANARC Rep: Jim Thomas, Back Issues: Dave Nieman, DECEMBER 2004 _______________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS Page Two 2 Mailbox 3 Finally! For those of you online with an email Satellite News… George Jensen 5 address, we now offer a quick, convenient TV News…Doug Smith 6 and secure way to join or renew your FM News…Adam Rivers 14 membership in the WTFDA from our page at: Photo News…Jeff Kruszka 20 Eastern TV DX…Matt Sittel 23 http://fmdx.usclargo.com/join.html Western TV DX…Victor Frank 25 Northern FM DX…Keith McGinnis 27 Dues are $25 if paid to our Paypal account. Translator News…Bruce Elving 34 But of course you can always renew by check Color TV History…Bob Cooper 37 or money order for the usual price of just $24. -

Exhibit 2181

Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 4 Electronically Filed Docket: 19-CRB-0005-WR (2021-2025) Filing Date: 08/24/2020 10:54:36 AM EDT NAB Trial Ex. 2181.1 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 2 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.2 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 3 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.3 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 4 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.4 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 132 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 1 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.5 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 133 Filed 04/15/20 Page 1 of 4 ATARA MILLER Partner 55 Hudson Yards | New York, NY 10001-2163 T: 212.530.5421 [email protected] | milbank.com April 15, 2020 VIA ECF Honorable Louis L. Stanton Daniel Patrick Moynihan United States Courthouse 500 Pearl St. New York, NY 10007-1312 Re: Radio Music License Comm., Inc. v. Broad. Music, Inc., 18 Civ. 4420 (LLS) Dear Judge Stanton: We write on behalf of Respondent Broadcast Music, Inc. (“BMI”) to update the Court on the status of BMI’s efforts to implement its agreement with the Radio Music License Committee, Inc. (“RMLC”) and to request that the Court unseal the Exhibits attached to the Order (see Dkt. -

Complete Report

Acknowledgments FMC would like to thank Jim McGuinn for his original guidance on playlist data, Joe Wallace at Mediaguide for his speedy responses and support of the project, Courtney Bennett for coding thousands of labels and David Govea for data management, Gabriel Rossman, Peter DiCola, Peter Gordon and Rich Bengloff for their editing, feedback and advice, and Justin Jouvenal and Adam Marcus for their prior work on this issue. The research and analysis contained in this report was made possible through support from the New York State Music Fund, established by the New York State Attorney General at Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors, the Necessary Knowledge for a Democratic Public Sphere at the Social Science Research Council (SSRC). The views expressed are the sole responsibility of its author and the Future of Music Coalition. © 2009 Future of Music Coalition Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 4 Programming and Access, Post-Telecom Act ........................................................ 5 Why Payola? ........................................................................................................... 9 Payola as a Policy Problem................................................................................... 10 Policy Decisions Lead to Research Questions...................................................... 12 Research Results .................................................................................................. -

North Carolina Storm Preparedness Landslides and Mudslides Alexander

County Emergency Coordinators Alamance.................................................................336-227-1365 North Carolina Storm Preparedness Landslides and Mudslides Alexander................................................................828-632-1139 Alleghany................................................................336-372-6220 Three-Day Disaster Supplies Kit Anson........................................................................704-694-4972 The best time to assemble a three-day disaster supplies kit is well before you will ever need it. Most people already have these items around the house and it is a matter of assembling them Debris flows, mudslides, mud flows, rock falls and rock slides are all types of landslides. Scientists have correlated a high likelihood of Ashe...........................................................................336-219-2521 now before an evacuation order is issued. debris flows being triggered when more than five inches of rain falls in western North Carolina in a 24-hour period. Debris flows are a fast Avery.........................................................................828-733-8210 Start with an easy to carry, watertight container — a large plastic trash can will do, or line a sturdy cardboard box with a couple of trash bags. Next gather up the following items and moving type of landslide that usually travel along stream channels below steep mountain slopes. They are also more common where new Beaufort ...................................................................252-946-2046 -

Public Notice >> Licensing and Management System Admin >>

REPORT NO. PN-2-191121-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 11/21/2019 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000079447 Renewal of FX W231DQ 200602 94.1 BRYSON CITY, NC FIVE FORTY 11/19/2019 Granted License BROADCASTING COMPANY, LLC 0000075273 Renewal of FX W253BA 141146 98.5 INDIAN TRAIL, NC POSITIVE 11/19/2019 Granted License ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000078180 Renewal of AM WWWC 22017 Main 1240.0 WILKESBORO, NC FOOTHILLS MEDIA, INC. 11/19/2019 Granted License 0000078227 Renewal of FM WFVL 41311 Main 102.3 LUMBERTON, NC EDUCATIONAL MEDIA 11/19/2019 Granted License FOUNDATION 0000079274 Renewal of FX W234AS 144135 94.7 BRYSON CITY, NC WESTERN NORTH 11/19/2019 Granted License CAROLINA PUBLIC RADIO 0000079151 Renewal of FM WHPE- 5164 Main 95.5 HIGH POINT, NC BIBLE BROADCASTING 11/19/2019 Granted License FM NETWORK, INC. 0000079726 Renewal of FM WUNC 66581 Main 91.5 CHAPEL HILL, NC WUNC PUBLIC RADIO, 11/19/2019 Granted License LLC 0000077353 Renewal of FX W206BY 92612 Main 89.1 SUMTER, SC PRIORITY RADIO, INC. 11/19/2019 Granted License Page 1 of 118 REPORT NO. PN-2-191121-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 11/21/2019 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. -

North Carolina Emergency Alert System State Plan

NORTH CAROLINA EMERGENCY ALERT SYSTEM Alleghany C Northampto Gates ur Ashe Surry Person P Ca r i tu Stokes Rockingham Caswell Vance Warren n a m c Granville Hertford s q de k Pe u o t n Halifax rq a n Watauga Wi lkes ui m k Yadkin a Forsyth Ch n s Franklin Bertie o w M Avery Guilford Alamance Orange a it c Durham n h e ll Caldwell Alexander Davie Nash Yancey Edgecombe Madison Martin Iredell Davidson Wake Washington Tyrell Dare Burke Chatham McDowell Randolph Wilson Catawba Haywood Buncombe Rowan Pitt Beaufort Hyde Swain Lee Johnston Rutherford Lincoln Greene Cabarrus Graham Henderson Jackson Stanly Moore Harnett Wayne Polk Cleveland Gaston nia Montgomery Lenoir Macon lva Mecklenbur Craven Cherokee nsy Tra g Clay Cumberland Pamlico Richmond Hoke Sampson Jones Union Anson Duplin Scotland Onslow Carteret Robeson Bladen Pender New Columbus Hanover Brunswick June 2005 STATE PLAN State of North Carolina Emergency Alert System Plan – June 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS...............................................................................................................1 I. INTENT AND PURPOSE OF THIS PLAN...................................................................4 II AUTHORITY ............................................................................................................................... 4 III. THE NATIONAL, STATE AND LOCAL EMERGERNCY ALERT SYSTEM: PARTICIPATION AND PRIORITIES ..........................................................................4 A. NATIONAL EMERGENCY ALERT SYSTEM PARTICIPATION…………… -

Federal Communications Commission Record 7 FCC Red No

FCC 92-426 Federal Communications Commission Record 7 FCC Red No. 22 lumbia residents, A business manager and the general man Before the ager spent four and t":o unspecified hours per week, Federal Communications Commission respectively, at the studiO. The Bureau found that this Washington, D.C. 20554 arrangement did not constitute a "main studio" and di rected Jones Eastern to take steps to assure a "meaningfuL management and staff presence" and to submit a progress Petition for Reconsideration report. and/or Clarification of . 3. Jones Eastern filed an application for review, challeng !fig the Bureau's determination that its studio did not meet Jones Eastern of the the staffing standard. In Jones Eastern of the Outer Banks, Outer Banks. Inc. Inc., 6 FCC Rcd 3615 (1991), we affirmed the Bureau. ruling that the occasional oversight of the managers did not Licensee, Radio Station WRSF(FM) constitute a meaningful presence. We stated that "a main Columbia. North Carolina studio must, at a minimum. maintain full-time managerial and full-time staff personnel." 6 FCC Rcd at 3616. We added that licensees need not have the same staff person MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER and manager at the studio, as long as there is management and staff presence during normal business hours. ld. at n.2. Adopted: September 3, 1992; Released: October 14, 1992 4. Jones Eastern now requests that the Commission re consider its decision on the basis of Jones Eastern's new By the Commission: staffing proposal, which consists of: 1) a full-time office worker; and 2) a full-time chief engineer. -

Country Update

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS SEPTEMBER 9, 2019 | PAGE 1 OF 22 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] Luke Bryan’s “Boots” Ken Burns’ Country Music Embraces Take A Big Step >page 4 A Genre’s Working-Class Connection Hurricane Relief Leads Country In classic storyteller fashion, Ken Burns’ Florentine Films Merle Haggard and The Carter Family — to make a name for Benefits team saved the most powerful moment in the upcoming PBS themselves by establishing a human connection through songs >page 11 series Country Music for the last of its eight episodes. about life’s emotional hardships. Kathy Mattea had fought an uphill battle to record “Where’ve “We say it’s all good old boys and pickup trucks and hound You Been,” a ballad about an aging couple separated in a hospital. dogs and six packs of beer,” says Burns. “That is an honorable, Despite an unconventional story and production, it became an and rather minor subgenre, of country music. But what it’s really Carrie, Church: unlikely hit in 1989, about is love and loss.” Country’s Good Sports and Mattea recounts Burns’ approach >page 12 in the series how a to documentaries is woman once appeared highly recognizable, in a meet-and-greet thanks to previous Aldean Fronts line, exchanging treatments of Truckload Of Albums tears and nods with Baseball, T h e Mattea as she got an Civil War, Jazz >page 12 autograph and a hug and Vietnam. The without saying a word. productions mesh BURNS MATTEA DUNCAN “Her husband just v i n t a g e p h o t o s , Makin’ Tracks: leaned down, and he sometimes-obscure Kip Moore’s Rocking grabbed her arm when they were walking away,” recalls Mattea footage and expert, on-camera interviews to place a topic in “She’s Mine” in the installment. -

North Carolina Emergency Alert System State Plan

North Carolina Emergency Alert System State Plan October 2019 Table of Contents Overview ........................................................................................................................................ 1 Authority ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Participation in and Priorities of the Emergency Alert System .......................................................... 2 Participation in the National System ............................................................................................................................... 2 Participation in the State and Local Systems ................................................................................................................... 3 Emergency Alert System Priorities .................................................................................................................................. 4 Activation Procedures for the Emergency Alert System .................................................................... 5 National Activation Procedures ....................................................................................................................................... 5 State Activation Procedures ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Local Activation Procedures ........................................................................................................................................... -

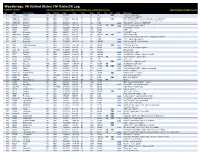

Woodbridge, VA (United States) FM Radio DX Log Updated 7/9/2021 Click Here to View Corresponding RDS/HD Radio Screenshots from This Log

Woodbridge, VA (United States) FM Radio DX Log Updated 7/9/2021 Click here to view corresponding RDS/HD Radio screenshots from this log. http://fmradiodx.wordpress.com/ Freq Calls City of License State Country Date Time Prop Miles ERP HD RDS Audio Information 87.7 W06CJ Fairfax VA USA 4/29/2007 Tr 10 10 RDS "Unison" - independent WDCN-LP Fairfax VA USA x/x/2010 Tr 10 3,000 "La Nueva 87.7" - spanish 87.7 WNDC-LP Salisbury MD USA 6/11/2017 4:10 AM Tr 83 250 RDS "Wow 101-5 and 87-7" - country, FM audio, over WDCN-LP WOWZ-LP Salisbury MD USA 6/8/2018 Tr 83 250 "Wow 87-7 and 99-3" - classic country, over WDCN-LP 87.7 WMTO-LP Moyock NC USA 5/23/2019 1:56 AM Tr 134 3,000 Audio "Streetz 87.7" - urban, over WDCN-LP 88.1 WYPR Baltimore MD USA 7/4/2006 10:17 PM Tr 56 10,000 HD RDS Audio "WYPR" - public radio, legal ID 88.1 WHOV Hampton VA USA 7/28/2006 10:08 AM Tr 125 2,000 "88.1 WHOV" - variety 88.1 KATG Athens TX USA 1/8/2007 7:32 PM Es 1136 88,000 "AFR" - ccm 88.1 KLBT Beaumont TX USA 5/9/2007 5:23 PM Es 1108 7,000 Audio "88.1 KLBT" - ccm 88.1 WMAW-FM Meridian MS USA 5/9/2007 5:45 PM Es 803 100,000 HD RDS "MPB" - public radio 88.1 WYPF Frederick MD USA 5/24/2007 1:02 AM Tr 58 1,000 "WYPR" - public radio, //WYPR 88.1, swapping with WYPR 88.1 WRIH Richmond VA USA 5/27/2007 3:01 AM Tr 77 2,000 Audio "AFR" - public radio, legal ID 88.1 WJIS Bradenton FL USA 5/31/2007 10:43 AM Es 850 100,000 Audio "88.1 The Joy FM" - ccm, local info WJIS Bradenton FL USA 6/16/2009 Es 850 100,000 "88.1 Joy FM" - ccm 88.1 WAYF West Palm Beach FL USA 5/31/2007 10:57 AM Es 851 50,000 RDS Audio "88.1 Way FM" - ccm 88.1 KAYT Jena LA USA 6/16/2007 4:33 PM Es 991 70,000 Audio "KAYT 88.1 FM" - gospel, legal ID 88.1 CBAL-FM-4 St.