A Guide to Developing a Severe Weather Emergency Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carrie's Cash

Carrie’s Cash - WKML Beasley Media Group’s Winter 2020 Nationwide Contest (Jan/Feb 2020) OFFICIAL RULES NO PURCHASE OR PAYMENT OF ANY KIND IS NECESSARY TO ENTER OR WIN (EXCEPT MESSAGE AND DATA RATES MAY APPLY). A PURCHASE OR PAYMENT OF ANY KIND WILL NOT INCREASE YOUR CHANCES OF WINNING. OPEN TO LEGAL RESIDENTS OF THE FIFTY (50) UNITED STATES AND WASHINGTON, DC, WHO ARE 18 YEARS OF AGE OR OLDER AT TIME OF ENTRY OR THE AGE OF MAJORITY IN THEIR STATE OF RESIDENCE. VOID WHERE PROHIBITED. 1. DESCRIPTION: The Beasley Media Group Winter 2020 Nationwide Contest (“Promotion”) begins on Monday, January 6, 2020, and will run through Monday, February 3, 2020, excluding Monday, January 20, 2020. The Promotion is being conducted by Beasley Media Group, LLC and its participating radio stations (the “Stations”) as listed below. The Promotion, known as “Carrie’s Cash” on the Stations, will begin on Monday, January 6, 2020, and will run through Monday, February 3, 2020, weekdays between the hours of 5am Pacific Time (“PT”) / 8am Eastern Time (“ET”) and 3:15pm PT / 6:15pm ET (“Promotion Period”). 2. SPONSOR: Sponsor coming soon! 3. ADMINISTRATOR: Beasley Media Group, LLC, 3033 Riviera Drive, Suite 200, Naples, FL 34103 4. ELIGIBILITY: The Promotion is open only to legal residents of the fifty (50) United States and District of Columbia (U.S.) who are at least eighteen (18) years of age or the age of majority in their state of residence, whichever is older as of date of entry (“Contestant”). Contestants will be competing with listeners from approximately forty seven (47) radio stations in multiple radio markets across the United States. -

SAGA COMMUNICATIONS, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

2017 Annual Report 2017 Annual Letter To our fellow shareholders: Every now and then I am introduced to someone who knows, kind of, who I am and what I do and they instinctively ask, ‘‘How are things at Saga?’’ (they pronounce it ‘‘say-gah’’). I am polite and correct their pronunciation (‘‘sah-gah’’) as I am proud of the word and its history. This is usually followed by, ‘‘What is a ‘‘sah-gah?’’ My response is that there are several definitions — a common one from 1857 deems a ‘‘Saga’’ as ‘‘a long, convoluted story.’’ The second one that we prefer is ‘‘an ongoing adventure.’’ That’s what we are. Next they ask, ‘‘What do you do there?’’ (pause, pause). I, too, pause, as by saying my title doesn’t really tell what I do or what Saga does. In essence, I tell them that I am in charge of the wellness of the Company and overseer and polisher of the multiple brands of radio stations that we have. Then comes the question, ‘‘Radio stations are brands?’’ ‘‘Yes,’’ I respond. ‘‘A consistent allusion can become a brand. Each and every one of our radio stations has a created personality that requires ongoing care. That is one of the things that differentiates us from other radio companies.’’ We really care about the identity, ambiance, and mission of each and every station that belongs to Saga. We have radio stations that have been on the air for close to 100 years and we have radio stations that have been created just months ago. -

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BTCCT-20061212AVR Communications, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CCF, et al. (Transferors) ) BTCH-20061212BYE, et al. and ) BTCH-20061212BZT, et al. Shareholders of Thomas H. Lee ) BTC-20061212BXW, et al. Equity Fund VI, L.P., ) BTCTVL-20061212CDD Bain Capital (CC) IX, L.P., ) BTCH-20061212AET, et al. and BT Triple Crown Capital ) BTC-20061212BNM, et al. Holdings III, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CDE, et al. (Transferees) ) BTCCT-20061212CEI, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212CEO For Consent to Transfers of Control of ) BTCH-20061212AVS, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212BFW, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting – Fresno, LLC ) BTC-20061212CEP, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting Operations, LLC; ) BTCH-20061212CFF, et al. AMFM Broadcasting Licenses, LLC; ) BTCH-20070619AKF AMFM Radio Licenses, LLC; ) AMFM Texas Licenses Limited Partnership; ) Bel Meade Broadcasting Company, Inc. ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; ) CC Licenses, LLC; CCB Texas Licenses, L.P.; ) Central NY News, Inc.; Citicasters Co.; ) Citicasters Licenses, L.P.; Clear Channel ) Broadcasting Licenses, Inc.; ) Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; and Jacor ) Broadcasting of Colorado, Inc. ) ) and ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BAL-20070619ABU, et al. Communications, Inc. (Assignors) ) BALH-20070619AKA, et al. and ) BALH-20070619AEY, et al. Aloha Station Trust, LLC, as Trustee ) BAL-20070619AHH, et al. (Assignee) ) BALH-20070619ACB, et al. ) BALH-20070619AIT, et al. For Consent to Assignment of Licenses of ) BALH-20070627ACN ) BALH-20070627ACO, et al. Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; ) BAL-20070906ADP CC Licenses, LLC; AMFM Radio ) BALH-20070906ADQ Licenses, LLC; Citicasters Licenses, LP; ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; and ) Clear Channel Broadcasting Licenses, Inc. ) Federal Communications Commission ERRATUM Released: January 30, 2008 By the Media Bureau: On January 24, 2008, the Commission released a Memorandum Opinion and Order(MO&O),FCC 08-3, in the above-captioned proceeding. -

THE WHY and Wherefore Or POOR RADIO RECEPTION

Modern radios are pack ed w ith features and refin ements that add immeasurably to radio enjoyment. Yet , no amount of radio improve - ments can increase th is enjoyment 'unless these improvements are u sed-and used properly . Ev en older radios are seldom operated to bring out the fine performance which they are WITH capable of giving . So , in justice to yourself and ~nninqhom the fi ne radio programs now being transmitted , ask yoursel f this questi on: "A m I getting as much enjoyment from my r ad io as possible?" Proper radio o per atio n re solves itself into a RADIO TUBES matter of proper tunin g. Yes , it's as simple as that . But you would be su rprised how few Hour aft er hour .. da y a nd night ... all ye ar people really know ho w t o tune a radio . In lon g . .. th e air is fill ed with star s who enter- Figure 1, the dial pointer is shown in the tain you. News broad casts ke ep you abrea st of middle of a shaded area . A certain station can be heard when the pointer covers any part of a swiftl y moving world . .. sport scast s brin g this shaded area , but it can only be heard you the tingling thrill of competition afield. enjo yably- clearl y and without distortion- Yet none of the se broadca sts can give you when the pointer is at dead center , midway between the point where the program first full sati sfaction unle ss you hear th em properl y. -

EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT Job Title Recruitment Source

EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT This Report covers full-time vacancy recruitment data for the period: July 23, 2018 – July 22, 2019. 1) Employment Unit: Beasley Media Group – Fayetteville, NC 2) Unit Members (Stations and Communities of License): WKML(FM), Lumberton, NC WAZZ(AM), Fayetteville, NC WFLB(FM), Laurinburg, NC WUKS(FM), St. Pauls, NC WZFX(FM), Whiteville, NC 3) EEO Contact Information for Employment Unit: Mailing Address: Telephone Number: 910-486-4114 508 Person Street Fayetteville, NC 28301 Contact Person/Title: Mandy Pittman/Assistant Business Manager E-mail Address: [email protected] 4) Full-Time Job Vacancies Filled by Each Station in the Employment Unit: Job Title Recruitment Source Referring Hiree (a) Traffic Manager Methodist University (b) Traffic Manager Employee Referral (c) Urban Brand Manager Employee Referral (d) Account Executive* Employee Referral, Intercompany Posting, Employee Referral (e) Program Director/Morning Show Host BBGI.COM (f) Digital Sales Specialist Client Referral (g) On-Air Talent WZFX FM Intercompany Posting (h) Digital / Promotions Coordinator Intercompany Posting (i) Creative Services Director Intercompany Posting (j) Account Executive Employee Referral (k) Chief Engineer / IT Director BBGI.COM (l) General Sales Manager BBGI.COM (m) NTR Promotions Director BBGI.COM Stations WKML(FM), WAZZ(AM), WFLB(FM), WUKS(FM) & WZFX(FM) are Equal Opportunity Employers. 1 Job Title Recruitment Source Referring Hiree (n) Morning Host/Marketing Consultant Employee Referral (o) Program Director/Morning Show Host -

He KMBC-ÍM Radio TEAM

l\NUARY 3, 1955 35c PER COPY stu. esen 3o.loe -qv TTaMxg4i431 BItOADi S SSaeb: iiSZ£ (009'I0) 01 Ff : t?t /?I 9b£S IIJUY.a¡:, SUUl.; l: Ii-i od 301 :1 uoTloas steTaa Rae.zgtZ IS-SN AlTs.aantur: aTe AVSí1 T E IdEC. 211111 111111ip. he KMBC-ÍM Radio TEAM IN THIS ISSUE: St `7i ,ytLICOTNE OSE YN in the 'Mont Network Plans AICNISON ` MAISHAIS N CITY ive -Film Innovation .TOrEKA KANSAS Heart of Americ ENE. SEDALIA. Page 27 S CLINEON WARSAW EMROEIA RUTILE KMBC of Kansas City serves 83 coun- 'eer -Wine Air Time ties in western Missouri and eastern. Kansas. Four counties (Jackson and surveyed by NARTB Clay In Missouri, Johnson and Wyan- dotte in Kansas) comprise the greater Kansas City metropolitan trading Page 28 Half- millivolt area, ranked 15th nationally in retail sales. A bonus to KMBC, KFRM, serv- daytime ing the state of Kansas, puts your selling message into the high -income contours homes of Kansas, sixth richest agri- Jdio's Impact Cited cultural state. New Presentation Whether you judge radio effectiveness by coverage pattern, Page 30 audience rating or actual cash register results, you'll find that FREE & the Team leads the parade in every category. PETERS, ñtvC. Two Major Probes \Exclusive National It pays to go first -class when you go into the great Heart of Face New Senate Representatives America market. Get with the KMBC -KFRM Radio Team Page 44 and get real pulling power! See your Free & Peters Colonel for choice availabilities. st SATURE SECTION The KMBC - KFRM Radio TEAM -1 in the ;Begins on Page 35 of KANSAS fir the STATE CITY of KANSAS Heart of America Basic CBS Radio DON DAVIS Vice President JOHN SCHILLING Vice President and General Manager GEORGE HIGGINS Year Vice President and Sally Manager EWSWEEKLY Ir and for tels s )F RADIO AND TV KMBC -TV, the BIG TOP TV JIj,i, Station in the Heart of America sú,\.rw. -

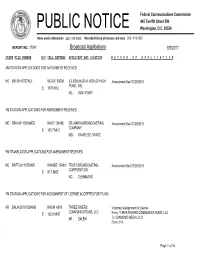

Broadcast Applications 8/3/2011

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 27542 Broadcast Applications 8/3/2011 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR AMENDMENT RECEIVED NC BR-20110727ACL WGOS 56508 IGLESIA NUEVA VIDA OF HIGH Amendment filed 07/29/2011 POINT, INC. E 1070 KHZ NC , HIGH POINT FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR AMENDMENT RECEIVED MD BRH-20110518AED WXCY 53488 DELMARVA BROADCASTING Amendment filed 07/29/2011 COMPANY E 103.7 MHZ MD , HAVRE DE GRACE FM TRANSLATOR APPLICATIONS FOR AMENDMENT RECEIVED NC BRFT-20110725AEI W249BZ 154301 TRUTH BROADCASTING Amendment filed 07/29/2011 CORPORATION E 97.7 MHZ NC , CLEMMONS FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING AR BALH-20110729AHB KHOM 6619 THREE RIVERS Voluntary Assignment of License COMMUNICATIONS, LLC E 100.9 MHZ From: THREE RIVERS COMMUNICATIONS, LLC AR , SALEM To: DIAMOND MEDIA, LLC Form 314 Page 1 of 44 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 27542 Broadcast Applications 8/3/2011 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING MO BALH-20110729AHC KBMV-FM 29623 THREE RIVERS Voluntary Assignment of License COMMUNICATIONS, LLC E 107.1 MHZ From: THREE RIVERS COMMUNICATIONS, LLC MO , BIRCH TREE To: DIAMOND MEDIA, LLC Form 314 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF PERMIT ACCEPTED FOR FILING MA BAPED-20110729AGI WJCI 177345 MORGAN BROOK CHRISTIAN Voluntary Assignment of Construction Permit RADIO, INC. -

OCEAN CITY, N.J. Morulng As the Guests of Mr

••LB XAJCB»-ConlloB«a Collector's Sale of Properties Tu i Let No.; 3tc. VaU Tax CoaU Pa-Mr ' Vain* ' Val. riknowo, lDlrra«ctlon aoulbcut alda or KnwkW.UeOofdy ISO) CO SMW I. looo i30 IIS K 70 for Unpaid Street Assessments. IrWO 00 41 76 6001» ii ao 70 Wain avenue, aoj feel aoulbweit of i B M n »•» 70 Klliy-afeoniSa-raetiaoutliwwiaco lert by ..„___ n» Ul III"!! •outbeMl to the Allan! o Ooean • 1100 00 • fj Si ti 06 iU OU n tu x nknown, inlWMctlnn aoulheaat aide of > 40 00 Wl Valin ,Ta»' Co.1 Wealay avenue, KM left aoulliweat or . Office of the Tni l"ollector, woo • m runk K.cliamplop.71 Moceui froDl.ln- flfly-aecond atreel, aoulUweaMWlNl by William MaliMr ID wuu batata 4 IH 2 00 ho on in iu liTxiH-llanimulknuiC Allnnlio avenue HBII , aolitbeaat lo Ibe AlUntloOoeuu * 200 10 auarTl toTh. Ctarl-f oi ^^ for pb H.Uonuo K>l. tun no III Kl m)iilhwml Moorlyn tsrnue, aoullimat 7i • nktiown, Intvnecllon anutheaal Hide of aulo at publlo auction nn William !*«• feel by MHitlwnit lu Uw Uoardwalk ' 2AW 00 470 Ml WOJ Wealey avenue, 4JO reel aoutbwial lo Kd woaioa woiu noil M.CumplKjll.-jr. rn-i oemn rnini<aauilira-l Kllly-Moond atr.el.aoutbweal W le*t by . lnuoou 41 08 2.1! a 05 Friday, the thJricenth dny of October, ibar, north cor- 1)00 OU liee»nuTenuo l» rwl •oulbwvui, rnnn • aoulbaaallo Ibe Atlantic Ocean 100 09 In omo ai m Tenili mmt, MII>UIW«I2A Ant bynuuin- nknown, tnlenwellan aonlbeaal aide of • ma oo vHwltotltB lloanlwaik astnoo . -

This EEO Report Covers the One Year Period Ending May 31, 2017

EEO Report This EEO Report covers the one year period ending May 31, 2017. During this period the station filled two full-time job vacancies. EEO Public File Report As of June 1, 2017 Positions Available: None Call Betty Parrish at: 434.797.4290 Or Mail to: P.O. Box 1629 Danville, Virginia 24543 Sources used for Part-Time Positions: WAKG/WBTM web site / on-air commercials Newspaper: Danville Register & Bee Sources used for Full-Time Positions: WAKG/WBTM web site / on-air commercials Newspaper: Danville Register & Bee Exhibit II EEO Public File Report This EEO Public File Report is filed in station WBTM’s Public Inspection File pursuant to section 73.2080 (e)(6) of the Federal Communications Commission's (FCC) rules. Exhibit III Piedmont Broadcasting Corporation June 1, 2017 Narrative Statement: In the past year there have been two full-time positions available, and filled. The turnover rate is very low at Piedmont Broadcasting Corporation because the seniority is greater than most other radio stations. The average employment tenure for the five most senior employees is now 32.0.. Our full-time employee average is 18.0, and all employees (full and part-time) have an average tenure of 32.0 years. Although our outreach efforts are many and consistent, being located in a non-metro market limits our number of qualified applicants. Our outreach program for the past year included the following: October 11, 2016 – WAKG & WBTM were represented as Platinum Sponsors in Southside Show-Biz Trade Show Tuesday, October 11, 2016 at Averett University’s North Campus. -

Federal Register Volume 31 • Number 209

FEDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 31 • NUMBER 209 Thursday, October 27, 1966 • Washington, D.C. Pages 13783-13830 Agencies in this issue— Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service Agriculture Department Atomic Energy Commission Commodity Credit Corporation Consumer and Marketing Service District of Columbia Redevelopment Land Agency Federal Aviation Agency Federal Communications Commission Federal Maritime Commission Federal Power Commission Federal Trade Commission Fiscal Service Food and Drug Administration Foreign Assets Control Office Interior Department Interstate Commerce Commission Land Management Bureau Navy Department Post Office Department Securities and Exchange Commission Detailed list of Contents appears inside. Current White House Releases ~ WEEKLY COMPILATION OF PRESIDENTIAL DOCUMENTS The Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents Issues at the end. Cumulation of this index terminates began with the issue dated Monday, August 2, 1965. at the end of each quarter and begins anew with the It contains transcripts erf the President’s news confer following issue. Semiannual and annual indexes, are ences, messages to Congress, public speeches, remarks and statements, and other Presidential material published separately. released by the White House up to 5 pjn. of each Friday. The Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents is This weekly service includes an Index of Contents sold to the public on a subscription basis. The price preceding the text and a Cumulative Index to Prior of individual copies varies. Subscription Price: -

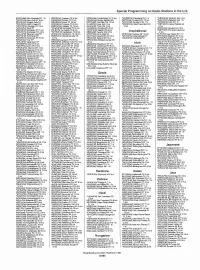

Special Programming on Radio Stations in the US Inspirational Irish

Special Programming on Radio Stations in the U.S. WOOX(AM) New Rochelle NV 1 hr WCDZ(FM) Dresden TN 4 hrs WRRA AMj Frederiksted VI 12 hrs ' WCSN(FM) Cleveland OH 1 hr 'WBRS(FM) Waltham MA 4 hrs WKCR-FM New York NY 2 hrs WSDO(AM) Dunlap TN 7 hrs KGNW AM) Burien -Seattle WA WKTX(AM) Cortland OH 12 hrs WZLY(FM) Wellesley MA 1 hr WHLD(AM) Niagara Falls NY WEMB(AM) Erwin TN 10 hrs KNTR( ) Ferndale WA 10 hrs WWKTL(FM) Struthers OH 1 hr WVFBE(FM) Flint MI 1 hr WXLG(FM) North Creek NY WHEW AM Franklin TN 3 hrs KLLM(FM) Forks WA 4 hrs WVQRP(FM) West Carrollton OH WVBYW(FM) Grand Rapids MI WWNYO(FM) Oswego NY 3 hrs WMRO AM Gallatin TN 13 tirs KVAC(AM) Forks WA 4 hrs 3 hrs 2 hrs WWXLU(FM) Peru NY WLMU(FM) Harrogate TN 4 hrs 'KAOS(FM) Olympia WA 2 hrs WSSJ(AM) Camden NJ 2 hrs WDKX(FM) Rochester NY 7 hrs WXJB -FM Harrogate TN 2 hrs KNHC(FM) Seattle WA 6 hrs WGHT(AM) Pompton Lakes NJ WWRU -FM Rochester NY 3 hrs WWFHC(FM) Henderson TN 5 hrs KBBO(AM) Yakima WA 2 hrs Inspirational 2 hrs WSLL(FM) Saranac Lake NY WHHM -FM Henderson TN 10 tirs WTRV(FM) La Crosse WI WFST(AM) Carbou ME 18 hrs KLAV(AM) Las Vegas NV 1 hr WMYY(FM) Schoharie NY WQOK(FM) Hendersonville TN WLDY(AM) Ladysmith 1M 3 hrs WVCIY(FM) Canandaigua NY WNYG(AM) Babylon NY 4 firs WVAER (FM) Syracuse NY 3 hrs 6 hrs WBJX(AM) Raane WI 8 hrs ' WCID(FM) Friendship NY WVOA(FM) DeRuyter NY 1 hr WHAZ(AM) Troy NY WDXI(AM) Jackson TN 16 hrs WRCO(AM) Rlohland Center WI WSI(AM) East Syracuse NY 1 hr WWSU(FM) Watertown NY WEZG(FM) Jefferson City TN 4 firs 3 hrs Irish WVCV FM Fredonia NY 3 hrs WONB(FM) Ada -

VAB Member Stations

2018 VAB Member Stations Call Letters Company City WABN-AM Appalachian Radio Group Bristol WACL-FM IHeart Media Inc. Harrisonburg WAEZ-FM Bristol Broadcasting Company Inc. Bristol WAFX-FM Saga Communications Chesapeake WAHU-TV Charlottesville Newsplex (Gray Television) Charlottesville WAKG-FM Piedmont Broadcasting Corporation Danville WAVA-FM Salem Communications Arlington WAVY-TV LIN Television Portsmouth WAXM-FM Valley Broadcasting & Communications Inc. Norton WAZR-FM IHeart Media Inc. Harrisonburg WBBC-FM Denbar Communications Inc. Blackstone WBNN-FM WKGM, Inc. Dillwyn WBOP-FM VOX Communications Group LLC Harrisonburg WBRA-TV Blue Ridge PBS Roanoke WBRG-AM/FM Tri-County Broadcasting Inc. Lynchburg WBRW-FM Cumulus Media Inc. Radford WBTJ-FM iHeart Media Richmond WBTK-AM Mount Rich Media, LLC Henrico WBTM-AM Piedmont Broadcasting Corporation Danville WCAV-TV Charlottesville Newsplex (Gray Television) Charlottesville WCDX-FM Urban 1 Inc. Richmond WCHV-AM Monticello Media Charlottesville WCNR-FM Charlottesville Radio Group (Saga Comm.) Charlottesville WCVA-AM Piedmont Communications Orange WCVE-FM Commonwealth Public Broadcasting Corp. Richmond WCVE-TV Commonwealth Public Broadcasting Corp. Richmond WCVW-TV Commonwealth Public Broadcasting Corp. Richmond WCYB-TV / CW4 Appalachian Broadcasting Corporation Bristol WCYK-FM Monticello Media Charlottesville WDBJ-TV WDBJ Television Inc. Roanoke WDIC-AM/FM Dickenson Country Broadcasting Corp. Clintwood WEHC-FM Emory & Henry College Emory WEMC-FM WMRA-FM Harrisonburg WEMT-TV Appalachian Broadcasting Corporation Bristol WEQP-FM Equip FM Lynchburg WESR-AM/FM Eastern Shore Radio Inc. Onley 1 WFAX-AM Newcomb Broadcasting Corporation Falls Church WFIR-AM Wheeler Broadcasting Roanoke WFLO-AM/FM Colonial Broadcasting Company Inc. Farmville WFLS-FM Alpha Media Fredericksburg WFNR-AM/FM Cumulus Media Inc.