Individualism and Commitment in Frank Capra's Mr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Box Office Digest (1941)

feojc Office (Zep&itd.: 'High Sierra' Week's Money Pic i>ee Pacje 5 * -i; r&; ?v^ • . -VT£i < - : -& % W 1 617 North La Brea Avenue, Los Angeies, Calif. Subscription Rate, #10.00 Per Year. .he Hex Ojfjfice DIGEST "HONOR BOX” The Biggest Grossing Release Of The Past Week This Week WARNERS wins with 'HIGH SIERRA' 115% Vice-Prcs. in Charge of Production Executive Producer Associate Producer Director JACK L. WARNER HAL WALLIS MARK HELLINGER RAOUL WALSH IDA LUPINO HUMPHREY BOGART Screenplay Featured ALAN CURTIS JOHN HUSTON ARTHUR KENNEDY W. R. BURNETT JOAN LESLIE HENRY HULL JEROME COWAN From Novel MINNA GOMBELL by BARTON McLANE W. R. BURNETT ELIZABETH RISDON CORNEL WILDE DONALD MacBRIDE PAUL HARVEY Photographer ISABEL JEWELL TONY GAUDIO WLLIE BEST SPENCER CHARTERS HENRY TRAVERS — ^Ue &Q4C Ofjfjice. ^JUe OnAuAisuyL DIGEST l/UeeJzhf, ENTERTAINMENT An Editorial by ROBERT E. WELSH The modest Editor last week murmered about the fact that it is release of life’s problems through zanie laughs, or complete the picture industry needs no legislative chiding—Senatorial abandonment of today’s calendar by adventure into glorious or otherwise—to tell it that heavy-handed propaganda, no mat- history, the first requirement of money-making entertainment ter for what side of an argument, is not selling theater tickets. is to take the customer away from his own daily problems. He just invited the attention of the pundits to the box office Above all, don’t aggravate those problems by preaching figures. And mentioned some of the pictures that were proving and especially sermonizing so effectively about the tragedies of the surprises. -

Torrance Herald

THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 21. 1935 Page 4 TORRANCE IfBRALD, Torrancp,-California BRITISH STAR of "Evergreen" is On the Double Bill At Fox Redondo Three Scintillating Stars Shine at Torrance "Bordertown" with Paul Muni FILM FIND Starting Sunday A Ucnn W. Levy romance as Opens at Lomita Tonight 1 »yinpalhctlcally treated na memorable Mm. MoonllBht." "fiapRgrutiflu' *«l<1 to embrace much splendor- as bus ever been crowded ,'irito" one iiTuittcal film, an a cant ill real favorites are .<ai to b'1 the ingredients of Cjaumon Uritlsh's currfnt offering at the Toiranre Theatre, Jessie Mat thews in "Kvcrsrrcen." The pic turn's <-ni,'UBc>mrnt will run thret nlchts starting tonight, as jmniun tu the feature, "Forsaking All Others." Miss Matthews Is the newest and one of the most sensatlona ' film finds of G. B. Production! :md lias had an enviable reputa- lio __ fit London previous to her eleva tion i', film .stardom. She played a bu!i<l y.-ar on the stage In "Ei green" )..-fore it was 1 transfel to tin- films. West of the Pecos" Opens Not'Sjnce "Dinner At Eight" motion picture created as much Tonight at Plaza Theatre Ivance discussion as Metro-Gold- yn - Mayor's newest offering, Hailed as the talking screen's two greatest portrayer* of emo'tion,, "Forsaking All Others," .which Barnum and His Tippling Aid< Paul Muni and Sette Davis smilingly regard the result of their greatest ihown tonight, Friday and,Sat dramaticmaic effort, the Warner Bros,ros, prouconproduction "Border-town,", in whichc urday at the Torrance Theatre star of ''I Am a Fugitive From the Chain Gang" and the sensatio i-ith a cast headed by three of "Of Human Bondage" reach new stellar heights. -

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

Vertigo. Revista De Cine (Ateneo Da Coruña)

Vertigo. Revista de cine (Ateneo da Coruña) Título: Frank Capra vs. Harry Langdon: El hombre cañón Autor/es: Pena, Jaime J. Citar como: Pena, JJ. (1992). Frank Capra vs. Harry Langdon: El hombre cañón. Vértigo. Revista de cine. (5):21-23. Documento descargado de: http://hdl.handle.net/10251/42953 Copyright: Todos los derechos reservados. Reserva de todos los derechos (NO CC) La digitalización de este artículo se enmarca dentro del proyecto "Estudio y análisis para el desarrollo de una red de conocimiento sobre estudios fílmicos a través de plataformas web 2.0", financiado por el Plan Nacional de I+D+i del Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad del Gobierno de España (código HAR2010-18648), con el apoyo de Biblioteca y Documentación Científica y del Área de Sistemas de Información y Comunicaciones (ASIC) del Vicerrectorado de las Tecnologías de la Información y de las Comunicaciones de la Universitat Politècnica de València. Entidades colaboradoras: FRANK CAPRA vs. HARRY LANGDO,N: 1.- HARRY LANGDON Fue Walter Montague, un viejo actor y propietario de una pequeña productora, quién EL HOMBRE introdujo a Frank Capra en el mundo del cine. O quizás deberíamos decir que fue a costa de ""' Walter Montague como Frank Capra se in CANON trodujo en el mundo del cine. Sea como fuere, Montague produjo a Capra su primer cortometraje, FULTAFtSHER'S BOARDING JAIME J. PENA HOUSE (1921), una adaptación de Rudyard Kipling que destaca por su crudeza y realismo, la cual le sirvió al hijo de emigrantes sicilianos para iniciarse en el cine aprendiendo el oficio a la inversa: primero como director, luego como montador, atrezzista, escritor de gags o lo que hiciese falta. -

February 4, 2020 (XL:2) Lloyd Bacon: 42ND STREET (1933, 89M) the Version of This Goldenrod Handout Sent out in Our Monday Mailing, and the One Online, Has Hot Links

February 4, 2020 (XL:2) Lloyd Bacon: 42ND STREET (1933, 89m) The version of this Goldenrod Handout sent out in our Monday mailing, and the one online, has hot links. Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. DIRECTOR Lloyd Bacon WRITING Rian James and James Seymour wrote the screenplay with contributions from Whitney Bolton, based on a novel by Bradford Ropes. PRODUCER Darryl F. Zanuck CINEMATOGRAPHY Sol Polito EDITING Thomas Pratt and Frank Ware DANCE ENSEMBLE DESIGN Busby Berkeley The film was nominated for Best Picture and Best Sound at the 1934 Academy Awards. In 1998, the National Film Preservation Board entered the film into the National Film Registry. CAST Warner Baxter...Julian Marsh Bebe Daniels...Dorothy Brock George Brent...Pat Denning Knuckles (1927), She Couldn't Say No (1930), A Notorious Ruby Keeler...Peggy Sawyer Affair (1930), Moby Dick (1930), Gold Dust Gertie (1931), Guy Kibbee...Abner Dillon Manhattan Parade (1931), Fireman, Save My Child Una Merkel...Lorraine Fleming (1932), 42nd Street (1933), Mary Stevens, M.D. (1933), Ginger Rogers...Ann Lowell Footlight Parade (1933), Devil Dogs of the Air (1935), Ned Sparks...Thomas Barry Gold Diggers of 1937 (1936), San Quentin (1937), Dick Powell...Billy Lawler Espionage Agent (1939), Knute Rockne All American Allen Jenkins...Mac Elroy (1940), Action, the North Atlantic (1943), The Sullivans Edward J. Nugent...Terry (1944), You Were Meant for Me (1948), Give My Regards Robert McWade...Jones to Broadway (1948), It Happens Every Spring (1949), The George E. -

Jean Harlow ~ 20 Films

Jean Harlow ~ 20 Films Harlean Harlow Carpenter - later Jean Harlow - was born in Kansas City, Missouri on 3 March 1911. After being signed by director Howard Hughes, Harlow's first major appearance was in Hell's Angels (1930), followed by a series of critically unsuccessful films, before signing with Metro-Goldwyn- Mayer in 1932. Harlow became a leading lady for MGM, starring in a string of hit films including Red Dust (1932), Dinner At Eight (1933), Reckless (1935) and Suzy (1936). Among her frequent co-stars were William Powell, Spencer Tracy and, in six films, Clark Gable. Harlow's popularity rivalled and soon surpassed that of her MGM colleagues Joan Crawford and Norma Shearer. By the late 1930s she had become one of the biggest movie stars in the world, often nicknamed "The Blonde Bombshell" and "The Platinum Blonde" and popular for her "Laughing Vamp" movie persona. She died of uraemic poisoning on 7 June 1937, at the age of 26, during the filming of Saratoga. The film was completed using doubles and released a little over a month after Harlow's death. In her brief life she married and lost three husbands (two divorces, one suicide) and chalked up 22 feature film credits (plus another 21 short / bit-part non-credits, including Chaplin's City Lights). The American Film Institute (damning with faint praise?) ranked her the 22nd greatest female star in Hollywood history. LIBERTY, BACON GRABBERS and NEW YORK NIGHTS (all 1929) (1) Liberty (2) Bacon Grabbers (3) New York Nights (Harlow left-screen) A lucky few aspiring actresses seem to take the giant step from obscurity to the big time in a single bound - Lauren Bacall may be the best example of that - but for many more the road to recognition and riches is long and grinding. -

Филмð¾ð³ñ€Ð°Ñ„иÑ)

Франк Капра Филм ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (ФилмографиÑ) The Broadway Madonna https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-broadway-madonna-3986111/actors Platinum Blonde https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/platinum-blonde-1124332/actors Prelude to War https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/prelude-to-war-1144659/actors That Certain Thing https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/that-certain-thing-1157116/actors Rain or Shine https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/rain-or-shine-1157168/actors State of the Union https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/state-of-the-union-1198352/actors Tunisian Victory https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/tunisian-victory-12129859/actors Pocketful of Miracles https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/pocketful-of-miracles-1219727/actors The Battle of Russia https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-battle-of-russia-1387285/actors Meet John Doe https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/meet-john-doe-1520732/actors Tramp, Tramp https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/tramp%2C-tramp-1540242/actors Lost Horizon https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/lost-horizon-1619885/actors Here Comes the Groom https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/here-comes-the-groom-1622567/actors Rendezvous in Space https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/rendezvous-in-space-17027654/actors Ladies of Leisure https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/ladies-of-leisure-1799948/actors The Miracle Woman https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-miracle-woman-1808053/actors Flight https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/flight-2032557/actors -

Title Call # Category Lang./Notes

Title Call # Category Lang./Notes K-19 : the widowmaker 45205 Kaajal 36701 Family/Musical Ka-annanā ʻishrūn mustaḥīl = Like 20 impossibles 41819 Ara Kaante 36702 Crime Hin Kabhi kabhie 33803 Drama/Musical Hin Kabhi khushi kabhie gham-- 36203 Drama/Musical Hin Kabot Thāo Sīsudāčhan = The king maker 43141 Kabul transit 47824 Documentary Kabuliwala 35724 Drama/Musical Hin Kadının adı yok 34302 Turk/VCD Kadosh =The sacred 30209 Heb Kaenmaŭl = Seaside village 37973 Kor Kagemusha = Shadow warrior 40289 Drama Jpn Kagerōza 42414 Fantasy Jpn Kaidan nobori ryu = Blind woman's curse 46186 Thriller Jpn Kaiju big battel 36973 Kairo = Pulse 42539 Horror Jpn Kaitei gunkan = Atragon 42425 Adventure Jpn Kākka... kākka... 37057 Tamil Kakushi ken oni no tsume = The hidden blade 43744 Romance Jpn Kakushi toride no san akunin = Hidden fortress 33161 Adventure Jpn Kal aaj aur kal 39597 Romance/Musical Hin Kal ho naa ho 41312, 42386 Romance Hin Kalyug 36119 Drama Hin Kama Sutra 45480 Kamata koshin-kyoku = Fall guy 39766 Comedy Jpn Kān Klūai 45239 Kantana Animation Thai Kanak Attack 41817 Drama Region 2 Kanal = Canal 36907, 40541 Pol Kandahar : Safar e Ghandehar 35473 Farsi Kangwŏn-do ŭi him = The power of Kangwon province 38158 Kor Kannathil muthamittal = Peck on the cheek 45098 Tamil Kansas City 46053 Kansas City confidential 36761 Kanto mushuku = Kanto warrior 36879 Crime Jpn Kanzo sensei = Dr. Akagi 35201 Comedy Jpn Kao = Face 41449 Drama Jpn Kaos 47213 Ita Kaosu = Chaos 36900 Mystery Jpn Karakkaze yarô = Afraid to die 45336 Crime Jpn Karakter = Character -

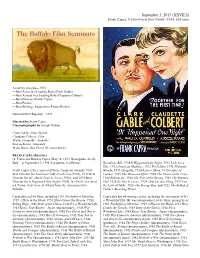

September 3, 2013 (XXVII:2) Frank Capra, IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT (1934, 105 Min)

September 3, 2013 (XXVII:2) Frank Capra, IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT (1934, 105 min) Academy Awards—1935: —Best Actor in a Leading Role (Clark Gable) —Best Actress in a Leading Role (Claudette Colbert) —Best Director (Frank Capra) —Best Picture —Best Writing, Adaptation (Robert Riskin) National Film Registry—1993 Directed by Frank Capra Cinematography by Joseph Walker Clark Gable...Peter Warne Claudette Colbert...Ellie Walter Connolly...Andrews Roscoe Karns...Shapeley Ward Bond...Bus Driver #1 (uncredited) FRANK CAPRA (director) (b. Francesco Rosario Capra, May 18, 1897, Bisacquino, Sicily, Italy—d. September 3, 1991, La Quinta, California) Broadway Bill, 1934 It Happened One Night, 1933 Lady for a Day, 1932 American Madness, 1932 Forbidden, 1931 Platinum Frank Capra is the recipient of three Academy Awards: 1939 Blonde, 1931 Dirigible, 1930 Rain or Shine, 1930 Ladies of Best Director for You Can't Take It with You (1938), 1937 Best Leisure, 1929 The Donovan Affair, 1928 The Power of the Press, Director for Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), and 1935 Best 1928 Submarine, 1928 The Way of the Strong, 1928 The Matinee Director for It Happened One Night (1934). In 1982 he received Idol, 1928 So This Is Love?, 1928 That Certain Thing, 1927 For a Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Film the Love of Mike, 1926 The Strong Man, and 1922 The Ballad of Institute. Fisher's Boarding House. Capra directed 54 films, including 1961 Pocketful of Miracles, Capra also has 44 writing credits, including the screenplay of It’s 1959 A Hole in the Head, 1951 Here Comes the Groom, 1950 a Wonderful Life. -

Gorinski2018.Pdf

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Automatic Movie Analysis and Summarisation Philip John Gorinski I V N E R U S E I T H Y T O H F G E R D I N B U Doctor of Philosophy Institute for Language, Cognition and Computation School of Informatics University of Edinburgh 2017 Abstract Automatic movie analysis is the task of employing Machine Learning methods to the field of screenplays, movie scripts, and motion pictures to facilitate or enable vari- ous tasks throughout the entirety of a movie’s life-cycle. From helping with making informed decisions about a new movie script with respect to aspects such as its origi- nality, similarity to other movies, or even commercial viability, all the way to offering consumers new and interesting ways of viewing the final movie, many stages in the life-cycle of a movie stand to benefit from Machine Learning techniques that promise to reduce human effort, time, or both. -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 2012 DVD-4759 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 21 Grams DVD-8358 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 10th Victim DVD-5591 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 12 DVD-1200 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 12 and Holding DVD-5110 25th Hour DVD-2291 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 12 Monkeys DVD-8358 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 DVD-3375 27 Dresses DVD-8204 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 28 Days Later DVD-4333 13 Going on 30 DVD-8704 28 Days Later c.2 DVD-4333 c.2 1776 DVD-0397 28 Days Later c.3 DVD-4333 c.3 1900 DVD-4443 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 1984 (Hurt) DVD-6795 3 Days of the Condor DVD-8360 DVD-4640 3 Women DVD-4850 1984 (O'Brien) DVD-6971 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 300 DVD-9078 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea DVD-8356 DVD-6064 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-8357 300: Rise of the Empire DVD-9092 DVD-0260 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 36th Chamber of Shaolin DVD-9181 1/25/2018 39 Steps DVD-0337 About Last Night DVD-0928 39 Steps c.2 DVD-0337 c.2 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 4 Films by Virgil Wildrich DVD-8361 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 -

CATALOGX 87.Pdf

E R T A N M E N T BIG NEWS, fRANIINSTBN, TIIE RDT•m VEIIIII (1831) BLACDAWK MOVESI \ Big news and good news for our many customers nationwide! Blackhawk Films, for years based in Davenport, Iowa is heading west to Hollywood. Effective September 18, 1987, Blackhawk Films moved its operations closer to the heart of the industry. The new facilities mean faster response and even more personal attention given to filling your orders. The most outstanding new feature that goes with the move is the extension of phone service to 24 hours a day, every day of the year. At Blackhawk Films, we keep trying to find new ways to retain our customers and give you the kind of service you deserve ... the best. You can see that effort most clearly in this catalog's selection of collectable entertainment. Just looking through our exclusive LANDMARKS IN ENTERTAINMENT Section gives you a taste of the kinds of special videocassettes we have to offer. Not just entertaining features, Blackhawk strives to select high-quality, important work that is valuable entertainment. Titles like the original FRANKENSTEIN, TOP HAT, DIRECTOR: James Whales PRODUCER: Carl Laemmle Jr. MAKE-UP: Jack Pierce CAST: Boris Ka.rfoff. Colin MR. SMITH GOES TO WASHINGTON, Clive, Mae Clarke, Edward Van Sloan, John Boles, Marilyn Harris and Dwight Frye SONS OF THE DESERT and the rest read like a roll call of the greatest films from For the first time in 50 years, this classic adaptation of Mary Shelly's novel can be seen the way its Hollywood's heyday.