Where's Gender? Evidence from Greek

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greece 2021, Krenik

GREECE Pilgrimage Including Greek Island Cruise Fr. Thomas Krenik Church of the Risen Savior September 26 - October 6, 2021 Accommodations Tour Inclusions More Information • Nine nights in 4-star • Breakfast daily, eight dinners, • Visit magitravelinc.com to accommodations: plus lunches on the cruise register online and view • Two nights: Mediterranean • Masses for the group more detailed information Palace, Thessaloniki • Gratuities for guides, drivers • One night: Divani Meteora, & cruise ship • Questions? Call Magi Travel Kalambaka at 952.949.0065 or email • Porterage of luggage • Three nights: Divani Palace [email protected] Acropolis, Athens • During land tour: • Three nights: Celestyal • Personal headsets Cruises including outside • Deluxe motorcoach cabins, port taxes & • Excellent local guide unlimited drink package Register Online: magitravelinc.com Visit Greece with Fr. Thomas Krenik and Church of the Risen Savior Follow the footsteps of Saint Paul through Philippi, Kavala, Veria, Corinth, and Athens. Set sail on a three-day cruise through the Greek isles. Visit ancient temples and idyllic seaside villages. Accompanied by an excellent local guide, experience the cultural, historical, and spiritual roots of the magnificent country of Greece. Let Magi Travel take you on one of their quality, custom tours which have been planned and perfected for over 35 years. Space is limited on this pilgrimage so sign up today! DAILY ITINERARY AT A GLANCE Sunday, September 26, 2021 Thursday, September 30 Monday, October 4 • USA to Thessaloniki, -

Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice | RSACVP 2017 | 6-9 April 2017 | Suceava – Romania Rethinking Social Action

Available online at: http://lumenpublishing.com/proceedings/published-volumes/lumen- proceedings/rsacvp2017/ 8th LUMEN International Scientific Conference Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice | RSACVP 2017 | 6-9 April 2017 | Suceava – Romania Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice The Convertor Status of Article of Case and Number in the Romanian Language Diana-Maria ROMAN* https://doi.org/10.18662/lumproc.rsacvp2017.62 How to cite: Roman, D.-M. (2017). The Convertor Status of Article of Case and Number in the Romanian Language. In C. Ignatescu, A. Sandu, & T. Ciulei (eds.), Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice (pp.682-694). Suceava, Romania: LUMEN Proceedings https://doi.org/10.18662/lumproc.rsacvp2017.62 © The Authors, LUMEN Conference Center & LUMEN Proceedings. Selection and peer-review under responsibility of the Organizing Committee of the conference 8th LUMEN International Scientific Conference Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice | RSACVP 2017 | 6-9 April 2017 | Suceava – Romania The Convertor Status of Article of Case and Number in the Romanian Language Diana-Maria ROMAN1* Abstract This study is the outcome of research on the grammar of the contemporary Romanian language. It proposes a discussion of the marked nominalization of adjectives in Romanian, the analysis being focused on the hypostases of the convertor (nominalizer). Within this area of research, contemporary scholarly treaties have so far accepted solely nominalizers of the determinative article type (definite and indefinite) and nominalizers of the vocative desinence type, in the singular. However, with regard to the marked conversion of an adjective to the large class of nouns, the phenomenon of enclitic articulation does not always also entail the individualization of the nominalized adjective, as an expression of the category of definite determination. -

Possessive Agreement Turned Into a Derivational Suffix Katalin É. Kiss 1

Possessive agreement turned into a derivational suffix Katalin É. Kiss 1. Introduction The prototypical case of grammaticalization is a process in the course of which a lexical word loses its descriptive content and becomes a grammatical marker. This paper discusses a more complex type of grammaticalization, in the course of which an agreement suffix marking the presence of a phonologically null pronominal possessor is reanalyzed as a derivational suffix marking specificity, whereby the pro cross-referenced by it is lost. The phenomenon in question is known from various Uralic languages, where possessive agreement appears to have assumed a determiner-like function. It has recently been a much discussed question how the possessive and non-possessive uses of the agreement suffixes relate to each other (Nikolaeva 2003); whether Uralic definiteness-marking possessive agreement has been grammaticalized into a definite determiner (Gerland 2014), or it has preserved its original possessive function, merely the possessor–possessum relation is looser in Uralic than in the Indo-Europen languages, encompassing all kinds of associative relations (Fraurud 2001). The hypothesis has also been raised that in the Uralic languages, possessive agreement plays a role in organizing discourse, i.e., in linking participants into a topic chain (Janda 2015). This paper helps to clarify these issues by reconstructing the grammaticalization of possessive agreement into a partitivity marker in Hungarian, the language with the longest documented history in the Uralic family. Hungarian has two possessive morphemes functioning as a partitivity marker: -ik, an obsolete allomorph of the 3rd person plural possessive suffix, and -(j)A, the productive 3rd person singular possessive suffix. -

The Religious Tourism As a Competitive Advantage of the Prefecture of Pieria, Greece

Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management, May-June 2021, Vol. 9, No. 3, 173-181 doi: 10.17265/2328-2169/2021.03.005 D DAVID PUBLISHING The Religious Tourism as a Competitive Advantage of the Prefecture of Pieria, Greece Christos Konstantinidis International Hellenic University, Serres, Greece Christos Mystridis International Hellenic University, Serres, Greece Eirini Tsagkalidou Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece Evanthia Rizopoulou International Hellenic University, Serres, Greece The scope of the present paper is the research of whether the prefecture of Pieria comprises an attractive destination for religious tourism and pilgrimage. For this reason, the use of questionnaires takes place which aims to realizing if and to what extend this form of tourism comprises a comparative and competitive advantage for the prefecture of Pieria. The research method of this paper is the qualitative research and more specifically the use of questionnaires with 13 questions in total. The scope was to research whether the prefecture of Pieria is a religious-pilgrimage destination. The sample is comprised of 102 participants, being Greek residents originating from other Greek counties, the European Union, and Third World Countries. The requirement was for the participant to have visited the prefecture of Pieria. The independency test (x2) was used for checking the interconnections between the different factors, while at the same time an allocation of frequencies was conducted based on the study and presentation of frequency as much as relevant frequency. Due to the fact that, no other similar former researches have been conducted regarding religious tourism in Pieria, this research will be able to give some useful conclusions. -

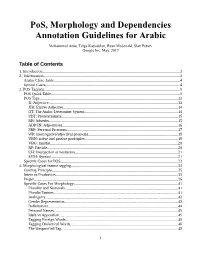

Pos, Morphology and Dependencies Annotation Guidelines for Arabic

PoS, Morphology and Dependencies Annotation Guidelines for Arabic Mohammed Attia, Tolga Kayadelen, Ryan Mcdonald, Slav Petrov Google Inc. May, 2017 Table of Contents 1. Introduction............................................................................................................................................2 2. Tokenization...........................................................................................................................................3 Arabic Clitic Table................................................................................................................................4 Special Cases.........................................................................................................................................4 3. POS Tagging..........................................................................................................................................8 POS Quick Table...................................................................................................................................8 POS Tags.............................................................................................................................................13 JJ: Adjective....................................................................................................................................13 JJR: Elative Adjective.....................................................................................................................14 DT: The Arabic Determiner System...............................................................................................14 -

Site Profiles - Greece

Site profiles - Greece This document provides detailed information on sites in Greece to allow for better planning and to address gaps where highlighted. The data will be updated on a monthly basis. All sites are managed by the Greek authorities. Data has been collected from different sources, i.e. UNHCR, site managers, Hellenic Police etc., and indicators are measured and based on the Sphere standards as outlined at the end of the document. Data was collected using key informants at the site and direct observation. Population figures are based on official estimates at site level. General overview Drama Serres-KEGE Cherso Kavala (Perigiali) Vagiochori Veria Lagkadikia A Nea Kavala Pieria (Petra Olympou) Pieria (Ktima Iraklis) Konitsa Giannitsa Derveni Tsepelovo (Alexil) Derveni Doliana Kipselochori Oreokastro (Dion-ABETE) Katsikas Trikala Sindos-Frakaport Diavata Kavalari Faneromeni (Atlantic) Volos Koutsochero Lesvos Alexandreia Softex Filipiada Sindos-Karamanli Vasilika Moria Kalochori Thessaloniki port A Thermopiles Chios Schisto Oinofyta Ritsona Malakasa Vial Elefsina Naval School Agios Andreas Andravidas Rafina Eleonas Skaramagas dock B Samos Vathy Transit sites Lavrio Lavrio (Accom. Facility) Informal sites and settlements Reception and Identification Centers (Closed facilities) Piraeus UNHCR Sub Office Leros Lepida UNHCR Country Office Kalymnos UNHCR Field Unit Temporary sites Kos Elliniko I Rhodes Elliniko II Elliniko III Megisti B 1 MAINLAND Attica Agios Andreas Elefsina Eleonas 1 & 2 Elaionas 3 Elliniko I (Hockey) Elliniko II -

Entomologia Hellenica

ENTOMOLOGIA HELLENICA Vol. 25, 2016 First record of the invasive species Parasaissetia nigra in Greece Tsagkarakis A. Laboratory of Agricultural Zoology and Entomology, Agricultural University of Athens, 11855, Athens, Greece Ben-Dov Y. Department of Entomology, Agricultural Research Organization, Bet Dagan 50250, Israel Papadoulis G. Laboratory of Agricultural Zoology and Entomology, Agricultural University of Athens, 11855, Athens, Greece https://doi.org/10.12681/eh.11546 Copyright © 2017 A. E. Tsagkarakis, Y. Ben-Dov, G. Th. Papadoulis To cite this article: Tsagkarakis, A., Ben-Dov, Y., & Papadoulis, G. (2016). First record of the invasive species Parasaissetia nigra in Greece. ENTOMOLOGIA HELLENICA, 25(1), 12-15. doi:https://doi.org/10.12681/eh.11546 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 21/04/2020 23:20:20 | ENTOMOLOGIA HELLENICA 25 (2016): 12-15 Received 04 September 2015 Accepted 04 March 2016 Available online 10 March 2016 SHORT COMMUNICATION First record of the invasive species Parasaissetia nigra in Greece A.E. TSAGKARAKIS1,*, Y. BEN-DOV2 AND G. TH. PAPADOULIS1 1Laboratory of Agricultural Zoology and Entomology, Agricultural University of Athens, 11855, Athens, Greece 2Department of Entomology, Agricultural Research Organization, Bet Dagan 50250, Israel ABSTRACT In June 2014, the nigra scale Parasaissetia nigra (Nietner) (Hemiptera: Coccidae) was recorded for the first time in Greece on pomegranate, Punica granatum. Its occurrence was observed in an ornamental pomegranate tree in the campus of the Agricultural University of Athens. Information on its morphology, biology and distribution is presented. KEY WORDS: nigra scale, Coccidae, pomegranate. Pomegranate is one of the first fruit trees Rodopi etc.). Nowadays, the estimated total cultivated in Greece and in the area with pomegranate orchards in Greece is Mediterranean region in general. -

Veria Site Snapshot 020118

VERIA SITE SNAPSHOT 2 January 2018 | Greece HIGHLIGHTS • 226 residents in the site of Veria, as of 31st of December 2017, including an unregistered family of 4. • 21 new arrivals were received throughout December from Chios and Evros border crossing. They were all provided with food and non-food items by NRC Shelter/WASH team. • 8 residents departed spontaneously and 13 under accommodation scheme. • Protection services, including Legal Assistance and Asylum Information are still provided by UNHCR, DRC, and EASO. • IRC is handling Psychosocial Support and Child Protection. Sexual/Gender-Based Violence or any other Protection cases are referred to UNHCR. • Healthcare Services are provided by Kitrinos with support from KEELPNO (public health actor). More than 60 children were vaccinated before their official starting date in Greek public schools. • The formal Kindergarten of MoE (Ministry of Education) started operating on site. • Bridge2 interrupted their activities early December (distribution of extra food, clothing, recreational activities) and stopped operating on site later the same month. • NRC Shelter/WASH program are continuously providing diesel fuel for the heating system which is operating for a total of 13 hours throughout the day. • IFRC replaced their cash-cards with new ones with extended expiration date. • NRC SMS arranged an excursion trip to Edessa waterfalls for 90 beneficiaries of the site, in the context of Geo-cultural integration activities. • Cooking contest was also held in the site and prizes awarded to the top 3 contestants by NRC SMS. • NRC SMS liaised 3 site residents with the local Municipality and helped participate in celebration for the World Human-Rights’ day in the context of social cohesion activities with the host community of Veria. -

In the Kingdom of Alexander the Great Ancient Macedonia

Advance press kit Exhibition From October 13, 2011 to January 16, 2012 Napoleon Hall In the Kingdom of Alexander the Great Ancient Macedonia Contents Press release page 3 Map of main sites page 9 Exhibition walk-through page 10 Images available for the press page 12 Press release In the Kingdom of Alexander the Great Exhibition Ancient Macedonia October 13, 2011–January 16, 2012 Napoleon Hall This exhibition curated by a Greek and French team of specialists brings together five hundred works tracing the history of ancient Macedonia from the fifteenth century B.C. up to the Roman Empire. Visitors are invited to explore the rich artistic heritage of northern Greece, many of whose treasures are still little known to the general public, due to the relatively recent nature of archaeological discoveries in this area. It was not until 1977, when several royal sepulchral monuments were unearthed at Vergina, among them the unopened tomb of Philip II, Alexander the Great’s father, that the full archaeological potential of this region was realized. Further excavations at this prestigious site, now identified with Aegae, the first capital of ancient Macedonia, resulted in a number of other important discoveries, including a puzzling burial site revealed in 2008, which will in all likelihood entail revisions in our knowledge of ancient history. With shrewd political skill, ancient Macedonia’s rulers, of whom Alexander the Great remains the best known, orchestrated the rise of Macedon from a small kingdom into one which came to dominate the entire Hellenic world, before defeating the Persian Empire and conquering lands as far away as India. -

A Spiritual Journey to Greece with a Greek Isle Cruise in the Footsteps of St

A Spiritual Journey to Greece with a Greek Isle Cruise In the Footsteps of St. Paul & the Early Christian Community Including Athens, Meteora, Thessaloniki, Philippi, Mykonos, Ephesus, Crete, Santorini, Corinth, Rhodes & More Suggested 14-Day Itinerary DAY 1: DEPART THE USA: We depart en route to Athens via substantial number of people who were receptive to the Gospel. New York, with complimentary meals & beverages served aloft. Paul returned through the area of Berea during his third missionary journey, and despite the earlier opposition, many of DAY 2: ARRIVE ATHENS: Upon our arrival in Athens, we are the Bereans were converted. We stop at the site, where tradition met by our Catholic Travel Centre representative and escorted to holds, the Apostle Paul stood and delivered his sermons. our private motor coach for transfer to our hotel to rest from our After our visit, we continue on to Thessaloniki. Paul journey. Dinner this evening is at our hotel. (D) established the first church here (Acts 17:1-10). Ruins of an early Christian church are near the Arch of Galerius, perhaps the DAY 3: ATHENS / KALAMBAKA: Today, we begin with Mass result of various plundering armies that invaded this region of at a local cathedral. Greece. We will visit Hagia Sophia, one of the oldest churches After Mass we enjoy still standing in Thessaloniki. St. Sophia, constructed in the a panoramic tour 8th century has been both a cathedral and a mosque. It was of Athens before we reconverted to a church in 1912. We also visit The Church of depart for the town of Saint Demetrius, the patron saint of Thessaloniki, dating from a Kalambaka, situated time when it was the second largest city of the Byzantine Empire. -

5 Adjectives and Adverbs

5 ADJECTIVES AND ADVERBS 1 Choose the correct alternative in the sentences below. If you find both alternatives acceptable, explain any difference in meaning. a. All the venues are easy/easily accessible. b. There’s a possible/possibly financial problem. c. We admired the wonderful/wonderfully panorama. d. Our neighbours are (simple)/simply people who live near us. Although less likely in this case, the adjective “simple” could be used as a premodifier to describe the noun (that is, the neighbours are not sophisticated people). Since the sentence seems to be a more general description of neighbours, however, the adverb “simply” is the more likely choice. The adverb serves as a comment on the part of the speaker. e. They seemed happy/happily about George’s victory. f. Similar/Similarly teams of medical advisers were called upon. g. Something in here smells horrible/horribly. Normally an adjective will follow a linking verb to describe a quality of the subject ref- erent. However, the adverb “horribly” can be used to refer to the intensity of the smell. h. This cream will give you a beautiful/beautifully smooth complexion. i. Particular/Particularly groups such as recent immigrants felt their needs were being overlooked. INTRODUCING ENGLISH GRAMMAR, THIRD EDITION KEY TO EXERCISES 5 Adjectives and Adverbs The adjective “particular” premodifies or describes the noun “groups”, whereas the use of the adverb “particularly” functions as a comment on the part of the speaker. 2 Explain the difference in form and meaning between the members of each pair. a. 1 She is a natural blonde. -

University of Education, Winneba College Of

University of Education, Winneba http://ir.uew.edu.gh UNIVERSITY OF EDUCATION, WINNEBA COLLEGE OF LANGUAGES EDUCATION, AJUMAKO THE SYNTAX OF THE GONJA NOUN PHRASE JACOB SHAIBU KOTOCHI May, 2017 i University of Education, Winneba http://ir.uew.edu.gh UNIVERSITY OF EDUCATION, WINNEBA COLLEGE OF LANGUAGES EDUCATION, AJUMAKO THE SYNTAX OF THE GONJA NOUN PHRASE JACOB SHAIBU KOTOCHI 8150260007 A thesis in the Department of GUR-GONJA LANGUAGES EDUCATION, COLLEGE OF LANGUAGES EDUCATION, submitted to the school of Graduate Studies, UNIVERSITY OF EDUCATION, WINNEBA in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the Master of Philosophy in Ghanaian Language Studies (GONJA) degree. ii University of Education, Winneba http://ir.uew.edu.gh DECLARATION I, Jacob Shaibu Kotochi, declare that this thesis, with the exception of quotations and references contained in published works and students creative writings which have all been identified and duly acknowledged, is entirely my own original work, and it has not been submitted, either in part or whole, for another degree elsewhere. Signature: …………………………….. Date: …………………………….. SUPERVISOR’S DECLARATION I, Dr. Samuel Awinkene Atintono, hereby declare that the preparation and presentation of this thesis were supervised in accordance with the guidelines for supervision of thesis as laid down by the University of Education, Winneba. Signature: …………………………….. Date: …………………………….. iii University of Education, Winneba http://ir.uew.edu.gh ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to express my gratitude to Dr. Samuel Awinkene Atintono of the Department of Gur-Gonja Languages Education, College of Languages Education for being my guardian, mentor, lecturer and supervisor throughout my university Education and the writing of this research work.