Joint Force Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 12, 2006 the Honorable John Warner, Chairman The

GENERAL JOHN SHALIKASHVILI, USA (RET.) GENERAL JOSEPH HOAR, USMC (RET.) ADMIRAL GREGORY G. JOHNSON, USN (RET.) ADMIRAL JAY L. JOHNSON, USN (RET.) GENERAL PAUL J. KERN, USA (RET.) GENERAL MERRILL A. MCPEAK, USAF (RET.) ADMIRAL STANSFIELD TURNER, USN (RET.) GENERAL WILLIAM G. T. TUTTLE JR., USA (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL DANIEL W. CHRISTMAN, USA (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL PAUL E. FUNK, USA (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL ROBERT G. GARD JR., USA (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL JAY M. GARNER, USA (RET.) VICE ADMIRAL LEE F. GUNN, USN (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL ARLEN D. JAMESON, USAF (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL CLAUDIA J. KENNEDY, USA (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL DONALD L. KERRICK, USA (RET.) VICE ADMIRAL ALBERT H. KONETZNI JR., USN (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL CHARLES OTSTOTT, USA (RET.) VICE ADMIRAL JACK SHANAHAN, USN (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL HARRY E. SOYSTER, USA (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL PAUL K. VAN RIPER, USMC (RET.) MAJOR GENERAL JOHN BATISTE, USA (RET.) MAJOR GENERAL EUGENE FOX, USA (RET.) MAJOR GENERAL JOHN L. FUGH, USA (RET.) REAR ADMIRAL DON GUTER, USN (RET.) MAJOR GENERAL FRED E. HAYNES, USMC (RET.) REAR ADMIRAL JOHN D. HUTSON, USN (RET.) MAJOR GENERAL MELVYN MONTANO, ANG (RET.) MAJOR GENERAL GERALD T. SAJER, USA (RET.) MAJOR GENERAL MICHAEL J. SCOTTI JR., USA (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL DAVID M. BRAHMS, USMC (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL JAMES P. CULLEN, USA (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL EVELYN P. FOOTE, USA (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL DAVID R. IRVINE, USA (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL JOHN H. JOHNS, USA (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL RICHARD O’MEARA, USA (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL MURRAY G. SAGSVEEN, USA (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL JOHN K. SCHMITT, USA (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL ANTHONY VERRENGIA, USAF (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL STEPHEN N. -

Brigadier General Kenneth Newton Walker

BRIGADIER GENERAL KENNETH NEWTON WALKER Died Jan. 5, 1943. Kenneth Newton Walker was born in Cerrillos, N.M., in 1898. He enlisted at Denver, Colo., Dec. 15, 1917 and took his flying training at the University of Californias School of Military Aeronautics and at Mather Field, Calif., getting his commission and wings in November 1918. He became a second lieutenant (temporary) in the Air Service Nov. 2, 1918 and received a commission in the regular Army July 1, 1920. For three years he was a flying instructor at Brooks and Barron Fields, Texas, and Fort Sill, Okla. In June 1922, 1st Lt. Walker graduated from the Air Service Operations School at Post Field, Okla. In December 1922, he went to the Philippines as Commander of the Air Intelligence Section at Camp Nichols. He returned to the United States in February 1925 as a member of the Air Service Board at Langley Field, Va. He stayed at Langley until 1928, having been adjutant of the 59th Service Squadron, commander of the 11th Bomb Squadron, and operations officer for the 2nd Bomb Group. He graduated from the Air Corps Tactical School at Langley Field in June 1929. After graduating, he served as an instructor at the ACTS until July 1931, when he became an instructor at Maxwell Field, Ala. He attended the Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kan., and graduated in June 1935. Major Walker went to Hamilton Field, Calif., where he served for three years as Intelligence and Operations Officer at the 7th Bomb Group, commander of the 9th Bomb Squadron and varied group duties. -

Army Downsizing Following World War I, World War Ii, Vietnam, and a Comparison to Recent Army Downsizing

ARMY DOWNSIZING FOLLOWING WORLD WAR I, WORLD WAR II, VIETNAM, AND A COMPARISON TO RECENT ARMY DOWNSIZING A thesis presented to the Faculty of the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MILITARY ART AND SCIENCE Military History by GARRY L. THOMPSON, USA B.S., University of Rio Grande, Rio Grande, Ohio, 1989 Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 2002 Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burder for this collection of information is estibated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing this collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burder to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (FROM - TO) 31-05-2002 master's thesis 06-08-2001 to 31-05-2002 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER ARMY DOWNSIZING FOLLOWING WORLD WAR I, WORLD II, VIETNAM AND 5b. -

Navy Personnel Command Gets Back to Business After Flood

® Serving the Hampton Roads Navy Family Vol. 18, No. 19, Norfolk, VA FLAGSHIPNEWS.COM May 13, 2010 Deborah Mullen speaks at CORE spouse leadership conference STORY AND PHOTOS BY MICHEAL T. MINK for the spouses in attendance. The Flagship Managing Editor Mullen was introduced to more than 150 spouses by Admiral “Provide continuing education John C. Harvey, Jr., Commander, for spouses to meet the unique U.S. Fleet Forces Command. challenges of a military lifestyle” “CORE is a very important pro- is the mission statement for Con- gram ... it was fi rst formed here tinuum Of Resource Education and the continuum of education or CORE – and there isn’t much for enlisted and offi cer spouses is more unique than fi tting the chal- a program that I am glad to see lenges of balancing an education fl ourishing,” said Mullen. into those of being a military A staunch advocate for military spouse. spouses and family readiness ef- The CORE Spring Conference forts, she said “I was asked to held at Naval Station Norfolk’s give a speech, but I really do not Vista Point Center, Monday, fea- like to do that.” Deborah Mullen tured Deborah Mullen, wife of “When I do that, I do not learn speaks at the CORE the Chairman, Joint Chiefs of anything from you and I will con- Spring Conference Staff, Adm. Mike Mullen. tinue to learn from you as long as held at Naval Station The theme for the conference my husband is lucky enough to Norfolk’s Vista Point – “What’s it all about? Challeng- serve,” she added. -

2021-2 Bio Book

BBIIOOGGRRAAPPHHIICCAALL DDAATTAA BBOOOOKK Keystone Class 2021-2 7-18 June 2021 National Defense University NDU PRESIDENT Lieutenant General Mike Plehn is the 17th President of the National Defense University. As President of NDU, he oversees its five component colleges that offer graduate-level degrees and certifications in joint professional military education to over 2,000 U.S. military officers, civilian government officials, international military officers and industry partners annually. Raised in an Army family, he graduated from Miami Southridge Senior High School in 1983 and attended the U.S. Air Force Academy Preparatory School in Colorado Springs, Colorado. He graduated from the U.S. Air Force Academy with Military Distinction and a degree in Astronautical Engineering in 1988. He is a Distinguished Graduate of Squadron Officer School as well as the College of Naval Command and Staff, where he received a Master’s Degree with Highest Distinction in National Security and Strategic Studies. He also holds a Master of Airpower Art and Science degree from the School of Advanced Airpower Studies, as well as a Master of Aerospace Science degree from Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University. Lt Gen Plehn has extensive experience in joint, interagency, and special operations, including: Middle East Policy in the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the Joint Improvised Explosive Device Defeat Organization, and four tours at the Combatant Command level to include U.S. European Command, U.S. Central Command, and twice at U.S. Southern Command, where he was most recently the Military Deputy Commander. He also served on the Air Staff in Strategy and Policy and as the speechwriter to the Vice Chief of Staff of the Air Force. -

Joint Chiefs of Staff” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 8, folder “12/11/76 - Joint Chiefs of Staff” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Betty Ford donated to the United States of America her copyrights in all of her unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Date Issued 12 / 3 / 76 ByP. Howard Revised FACT SHEET Mrs. F orct 's Office fa·cnt Dinne r Group Joint_ Chiefs of Staff, Service Secretaries and United Commanders DATE/Tm1E Saturday, December 11, 1976 7:30 p. m. Contact Pat---------------------------- Howard Phone 292 7 Number of guests: Total approx . 50 x Children Place State Floor Principals involved President and Mrs. Ford Participation by PrinCipal __.__e_s ________ ____:(Receiving line )_--"'-e_s__________ _ Remarks required ___:....____yes _______________ _____________~ Ibckgrounct ----~----------------------------------- REQTJ JRPMENTS Social: Guest list yes - Social Entertainments office will distribute guest list. I nvitations__ _,,_y_e_s _______ ______ Programs _n_o___ Menus yes Refreshments---------- Dinner Format---- ----------------· Fntertainmcnt yes - Military Musical Units ---'------~'---------------------~· Decorations/flowers---=------- yes -------------------- Music yes Social Aiclcs -=--------------yes Drc~s Black Tie Coat check yes- DRR Other --- - ----------- Pre ~,: g cpnrtcrs TO BE RESOLVED !'llotorra11hcrs_____ _ TV Crews \':ilitc Hollsc l'hotorrnrhers_ YES Color YES Mono. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Indra Lusero, Assistant Director

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Indra Lusero, Assistant Director, 303-902-9402, [email protected] SCHOLAR ASSESSES COLIN POWELL'S LATEST REMARKS Powell is Second Joint Chiefs Chair to Urge Review of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” Date: December 15, 2008 SANTA BARBARA, December 14, 2008 – General Colin Powell said this week that the nation “definitely should re-evaluate” the current ban on openly gay troops. “It’s been fifteen years and attitudes have changed,” he told CNN in an interview. Powell, who was Secretary of State under George Bush, was Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in 1993 when “don’t ask, don’t tell” became law. The policy requires gay and lesbian troops to conceal their sexual identity and remain celibate. Dr. Nathaniel Frank, a historian and senior research fellow at the Palm Center, says that Powell’s remarks reflect a small but important change in the General’s public position. “In previous comments,” Frank said, “Powell called for reviewing ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ at the same time that he said he was not ready to advocate its elimination. This time is different: in the wake of Obama’s victory, repeal has a real chance, and Powell’s slightly stronger remarks—that we should, instead of could, reconsider the policy, add more to the momentum for change.” Frank’s forthcoming book, Unfriendly Fire: How the Gay Ban Undermines the Military and Weakens America, includes a chapter on Powell’s participation in the 1993 debates, and documents Powell’s central role in assuring the legislating of the ban. -

Congressional Record—House H2574

H2574 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE May 19, 2021 Sewell (DelBene) Wilson (FL) Young (Joyce NAYS—208 Ruppersberger Slotkin (Axne) Wilson (SC) Slotkin (Axne) (Hayes) (OH)) (Raskin) Waters (Timmons) Aderholt Gohmert Moolenaar Waters Wilson (SC) Rush (Barraga´ n) Young (Joyce Allen (Barraga´ n) (Timmons) Gonzales, Tony Mooney (Underwood) Wilson (FL) Amodei (OH)) Gonzalez (OH) Moore (AL) Sewell (DelBene) (Hayes) The SPEAKER pro tempore. The Armstrong Good (VA) Moore (UT) question is on the resolution. Arrington Gooden (TX) Mullin f Babin Gosar Murphy (NC) The question was taken; and the Bacon Granger Nehls NATIONAL COMMISSION TO INVES- Speaker pro tempore announced that Baird Graves (LA) Newhouse TIGATE THE JANUARY 6 ATTACK the ayes appeared to have it. Balderson Graves (MO) Norman Banks Green (TN) Nunes ON THE UNITED STATES CAP- Mr. RESCHENTHALER. Mr. Speak- Barr Greene (GA) Obernolte ITOL COMPLEX ACT Bentz Griffith er, on that I demand the yeas and nays. Owens Mr. THOMPSON of Mississippi. Mr. Bergman Grothman Palazzo The SPEAKER pro tempore. Pursu- Bice (OK) Guest Palmer Speaker, pursuant to House Resolution ant to section 3(s) of House Resolution Biggs Guthrie Pence 409, I call up the bill (H.R. 3233) to es- 8, the yeas and nays are ordered. Bilirakis Hagedorn Perry tablish the National Commission to In- Bishop (NC) Harris Pfluger The vote was taken by electronic de- Boebert Harshbarger Posey vestigate the January 6 Attack on the vice, and there were—yeas 216, nays Bost Hartzler Reed United States Capitol Complex, and for 208, not voting 5, as follows: Brady Hern Reschenthaler other purposes, and ask for its imme- Brooks Herrell Rice (SC) diate consideration. -

Marine Option Program. First Biennial Report. INSTITUTION Hawaii Univ., Honolulu

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 093 665 SE 017 756 AUTHOR Hill, Barry H. TITLE Marine Option Program. First Biennial Report. INSTITUTION Hawaii Univ., Honolulu. Sea Grant Program. SPONS AGENCY National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (DOC), Rockville, Md. National Sea Grant Program. REPORT NO UNIHI-SEAGRANT-MS-73-02 PUB DATE Jun 73 NOTE 70p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$3.15 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Curriculum; *Marine Biology; *program Descriptions; Research; *Research Projects; Science Education; Science Programs; *Undergraduate Study IDENTIFIERS Marine Option Program; MOP ABSTRACT This report describes a marine studies program sponsored by the University of Hawaii. The publication presents the students' own stories pf their experiences. An overview of the kind of program, student qualifications and requirements, and scope of the Marine Option Program (MOP) is included in the report. Details are provided relating to (1) the program's objectives, (2) its methods of operation, and (3) the progress it has made. Tile academic development, marine skill development, and extension of the program are discussed. A complete _fiscal report is presented, both in descriptive and tabulated form, for the period March 1, 1972-August 31, 1973. (EB) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZAI ION ORIGIN ATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRE SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. FIRST BIENNIAL REPORT MARINE OPTION PROGRAM Sea Grant Miscellaneous Report UNIHI-SEAGRANT-MS-73-02 June 1973 Barry H. Hill Assistant for Curriculum Development Office of Marine Programs o This biennial reportdescribes the Program sponsored by the Universityof Hawaii and NOAH Office of Sea Grant, Department of Commerce, under , Grant Nos. -

DEPARTMENT of DEFENSE Office of the Secretary, the Pentagon, Washington, DC 20301–1155 Phone, 703–545–6700

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE Office of the Secretary, The Pentagon, Washington, DC 20301±1155 Phone, 703±545±6700 SECRETARY OF DEFENSE WILLIAM S. COHEN Deputy Secretary of Defense JOHN P. WHITE Special Assistants to the Secretary and JAMES M. BODNER, ROBERT B. Deputy Secretaries of Defense HALL, SCOTT A. HARRIS Executive Secretary COL. JAMES N. MATTIS, USMC Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and PAUL G. KAMINSKI Technology Principal Deputy Under Secretary of Defense NOEL LONGUEMARE, JR. for Acquisition and Technology Director, Defense Research and Engineering ANITA K. JONES Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for HAROLD P. SMITH, JR. Nuclear and Chemical and Biological (NCB) Defense Programs Deputy Under Secretary of Defense (Space) (VACANCY) Deputy Under Secretary of Defense JOHN M. BACHKOSKY (Advanced Technology) Deputy Under Secretary of Defense SHERRI W. GOODMAN (Environmental Security) Deputy Under Secretary of Defense JOHN F. PHILLIPS (Logistics) Deputy Under Secretary of Defense (VACANCY) (Acquisition Reform) Deputy Under Secretary of Defense PAUL J. HOPPER (International and Commercial Programs) Deputy Under Secretary of Defense JOHN B. GOODMAN (Industrial Affairs and Installations) Director, Small and Disadvantaged Business ROBERT L. NEAL, JR. Utilization Under Secretary of Defense for Policy WALTER B. SLOCOMBE Principal Deputy Under Secretary of Defense JAN M. LODAL for Policy Assistant Secretary of Defense (International FRANKLIN D. KRAMER Security Affairs) Assistant Secretary of Defense (International FRANKLIN C. MILLER, Acting Security Policy) Assistant Secretary of Defense (Strategy, EDWARD L. WARNER III Requirements, and Assessments) Director of Net Assessment ANDREW W. MARSHALL Assistant Secretary of Defense (Special H. ALLEN HOLMES Operations and Low-Intensity Conflict) Defense Adviser, U.S. -

Americanlegionvo1356amer.Pdf (9.111Mb)

Executive Dres WINTER SLACKS -|Q95* i JK_ J-^ pair GOOD LOOKING ... and WARM ! Shovel your driveway on a bitter cold morning, then drive straight to the office! Haband's impeccably tailored dress slacks do it all thanks to these great features: • The same permanent press gabardine polyester as our regular Dress Slacks. • 1 00% preshrunk cotton flannel lining throughout. Stitched in to stay put! • Two button-thru security back pockets! • Razor sharp crease and hemmed bottoms! • Extra comfortable gentlemen's full cut! • 1 00% home machine wash & dry easy care! Feel TOASTY WARM and COMFORTABLE! A quality Haband import Order today! Flannel 1 i 95* 1( 2 for 39.50 3 for .59.00 I 194 for 78. .50 I Haband 100 Fairview Ave. Prospect Park, NJ 07530 Send REGULAR WAISTS 30 32 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 pairs •BIG MEN'S ADD $2.50 per pair for 46 48 50 52 54 INSEAMS S( 27-28 M( 29-30) L( 31-32) XL( 33-34) of pants ) I enclose WHAT WHAT HOW 7A9.0FL SIZE? INSEAM7 MANY? c GREY purchase price D BLACK plus $2.95 E BROWN postage and J SLATE handling. Check Enclosed a VISA CARD# Name Mail Address Apt. #_ City State .Zip_ 00% Satisfaction Guaranteed or Full Refund of Purchase $ § 3 Price at Any Time! The Magazine for a Strong America Vol. 135, No. 6 December 1993 ARTICLE s VA CAN'T SURVIVE BY STANDING STILL National Commander Thiesen tells Congress that VA will have to compete under the President's health-care plan. -

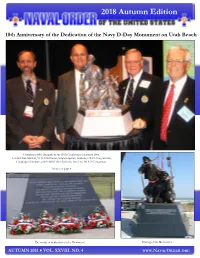

2018 Autumn Edition

2018 Autumn Edition 10th Anniversary of the Dedication of the Navy D-Day Monument on Utah Beach Unveiling of the Maquette at the SNA Conference in Jan uary 2006. L to R: Dean Mosher, NOUS Historian; Stephen Spears, sculptor; CAPT Greg Streeter, Campaign Chairman; and VADM Mike Kalleres, 1st Coast NOUS Companion. Article on page 4 The words of dedication on the Monument Placing of the Monument AUTUMN 2018 ● VOL. XXVIII, NO. 4 WWW.NAVALORDER.ORG COMMANDER GENERAL ’S REPORT TO THE ORDER 2018 Congress in San Antonio - What to On Saturday morning, 27 October, after a continental breakfast, remaining national officer reports will be made followed by a Look Forward to…or What You’re Missing presentation by citizen sailor, businessman and author, CAPT The Texas Commandery is hosting the 2018 Congress at the Mark Liebmann. Wyndam San Antonio Riverwalk from Wednesday, 24 The Admiral of the Navy George Dewey Award/Commander October through 27 October and assures us that our visit to General Awards Luncheon will recognize Mr. Marshall Cloyd, the Lone Star state will be most memorable. recipient of The Admiral of the Navy George Dewey Award. Although the Congress doesn’t officially start until Additionally, RADM Douglas Moore, USN (Ret.) will Wednesday, we will visit the National Museum of the Pacific receive the Distinguished Alumnus Award by the Navy Supply Corps Foundation. War (Nimitz Museum) in Fredericksburg, TX on Tuesday, 23 October. Similar to the National World War II Museum that After lunch a presentation will be made by James Hornfischer, one many of us visited during our 2015 Congress in New of the most commanding naval historians writing today.