(2020). California Chaparral and Woodlands. Reference Module In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palm Haven Garden Plant List - 2010

PALM HAVEN GARDEN PLANT LIST - 2010 BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME Achillea millefolium 'Paprika' Paprika yarrow Arctostaphylos glauca big berry manzanita Arctostaphylos pajaroensis Pajaro manzanita Arctostaphylos uva-ursi bearberry Arctostaphylos uva-ursi 'San Bruno Mountain' San Bruno Mountain bearberry Aristolochia californica California pipevine Artemisia pycnocephala coastal sagewort Baccharis pilularis 'Twin Peaks' Twin Peaks dwarf coyote brush Berberis aquifolium 'Golden Abundance' Golden Abundance Oregon-grape Carex spissa San Diego sedge Ceanothus 'Joyce Coulter' Joyce Coulte wild lilac Ceanothus arboreus feltleaf ceanothus Ceanothus gloriosus var exaltatus 'Emily Brown' Emily Brown glory brush Dendromecon harfordii Channel Island tree poppy Epilobium canum California fuchsia Erigeron glaucus seaside daisy Eriogonum fasciculatum California buckwheat Eriogonum latifolium coast buckwheat Eriogonum umbellatum sulfur flower Eriophyllum confertiflorum golden yarrow Heteromeles arbutifolia toyon Heterotheca sessilifolora false goldenaster Iris douglasiana Douglas iris Leymus condensatus 'Canyon Prince' Canyon Prince giant wild rye Mimulus aurantiacus sticky monkeyflower Monardella villosa coyote mint Mulhenbergia rigens deer grass Penstemon heterophyllus foothill penstemon Physocarpus capitatus ninebark Rhamnus californica 'Ed Holm' Ed Holm coffeeberry Rhamnus californica 'Mound San Bruno' Mound San Bruno coffeeberry Salvia clevelandii Cleveland sage Salvia mellifera 'Shirley's Creeper' Shirley's Creepe sage Salvia sonomensis 'Bee's Bliss' Bee's Bliss sage Satureja douglasii yerba buena Trichostema lanatum wolly blue curls Typha angustifolia narrow-leaved cattail Verbena lilacina lilac verbena Vitis californica 'Roger's Red' Roger's Red California wild grape. -

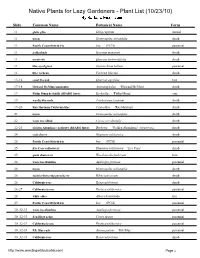

Native Plants for Lazy Gardeners - Plant List (10/23/10)

Native Plants for Lazy Gardeners - Plant List (10/23/10) Slide Common Name Botanical Name Form 11 globe gilia Gilia capitata annual 11 toyon Heteromeles arbutifolia shrub 11 Pacific Coast Hybrid iris Iris (PCH) perennial 11 goldenbush Isocoma menziesii shrub 11 scrub oak Quercus berberidifolia shrub 11 blue-eyed grass Sisyrinchium bellum perennial 11 lilac verbena Verbena lilacina shrub 13-16 coast live oak Quercus agrifolia tree 17-18 Howard McMinn man anita Arctostaphylos 'Howard McMinn' shrub 19 Philip Mun keckiella (RSABG Intro) Keckiella 'Philip Munz' ine 19 woolly bluecurls Trichostema lanatum shrub 19-20 Ray Hartman California lilac Ceanothus 'Ray Hartman' shrub 21 toyon Heteromeles arbutifolia shrub 22 western redbud Cercis occidentalis shrub 22-23 Golden Abundance barberry (RSABG Intro) Berberis 'Golden Abundance' (MAHONIA) shrub 2, coffeeberry Rhamnus californica shrub 25 Pacific Coast Hybrid iris Iris (PCH) perennial 25 Eve Case coffeeberry Rhamnus californica '. e Case' shrub 25 giant chain fern Woodwardia fimbriata fern 26 western columbine Aquilegia formosa perennial 26 toyon Heteromeles arbutifolia shrub 26 fuchsia-flowering gooseberry Ribes speciosum shrub 26 California rose Rosa californica shrub 26-27 California fescue Festuca californica perennial 28 white alder Alnus rhombifolia tree 29 Pacific Coast Hybrid iris Iris (PCH) perennial 30 032-33 western columbine Aquilegia formosa perennial 30 032-33 San Diego sedge Carex spissa perennial 30 032-33 California fescue Festuca californica perennial 30 032-33 Elk Blue rush Juncus patens '.l1 2lue' perennial 30 032-33 California rose Rosa californica shrub http://www weedingwildsuburbia com/ Page 1 30 032-3, toyon Heteromeles arbutifolia shrub 30 032-3, fuchsia-flowering gooseberry Ribes speciosum shrub 30 032-3, Claremont pink-flowering currant (RSA Intro) Ribes sanguineum ar. -

The Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Bird Conservation Plan

The Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Bird Conservation Plan A Strategy for Protecting and Managing Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Habitats and Associated Birds in California A Project of California Partners in Flight and PRBO Conservation Science The Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Bird Conservation Plan A Strategy for Protecting and Managing Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Habitats and Associated Birds in California Version 2.0 2004 Conservation Plan Authors Grant Ballard, PRBO Conservation Science Mary K. Chase, PRBO Conservation Science Tom Gardali, PRBO Conservation Science Geoffrey R. Geupel, PRBO Conservation Science Tonya Haff, PRBO Conservation Science (Currently at Museum of Natural History Collections, Environmental Studies Dept., University of CA) Aaron Holmes, PRBO Conservation Science Diana Humple, PRBO Conservation Science John C. Lovio, Naval Facilities Engineering Command, U.S. Navy (Currently at TAIC, San Diego) Mike Lynes, PRBO Conservation Science (Currently at Hastings University) Sandy Scoggin, PRBO Conservation Science (Currently at San Francisco Bay Joint Venture) Christopher Solek, Cal Poly Ponoma (Currently at UC Berkeley) Diana Stralberg, PRBO Conservation Science Species Account Authors Completed Accounts Mountain Quail - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Greater Roadrunner - Pete Famolaro, Sweetwater Authority Water District. Coastal Cactus Wren - Laszlo Szijj and Chris Solek, Cal Poly Pomona. Wrentit - Geoff Geupel, Grant Ballard, and Mary K. Chase, PRBO Conservation Science. Gray Vireo - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Black-chinned Sparrow - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Costa's Hummingbird (coastal) - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Sage Sparrow - Barbara A. Carlson, UC-Riverside Reserve System, and Mary K. Chase. California Gnatcatcher - Patrick Mock, URS Consultants (San Diego). Accounts in Progress Rufous-crowned Sparrow - Scott Morrison, The Nature Conservancy (San Diego). -

Adenostoma Fasciculatum Profile to Postv2.Xlsx

I. SPECIES Adenostoma fasciculatum Hooker & Arnott NRCS CODE: ADFA Family: Rosaceae A. f. var. obtusifolium, Ron A. f. var. fasciculatum., Riverside Co., A. Montalvo, RCRCD Vanderhoff (Creative Order: Rosales Commons CC) Subclass: Rosidae Class: Magnoliopsida A. Subspecific taxa 1. Adenostoma fasciculatum var. fasciculatum Hook. & Arn. 1. ADFAF 2. A. f. var. obusifolium S. Watson 2. ADFAO 3. A. f. var. prostratum Dunkle 3. (no NRCS code) B. Synonyms 1. A. f. var. densifolium Eastw. 2. A. brevifolium Nutt. 3. none. Formerly included as part of A. f. var. f. C. Common name 1. chamise, common chamise, California greasewood, greasewood, chamiso (Painter 2016) 2. San Diego chamise (Calflora 2016) 3. prostrate chamise (Calflora 2016) Phylogenetic studies using molecular sequence data placedAdenostoma closest to Chamaebatiaria and D. Taxonomic relationships Sorbaria (Morgan et al. 1994, Potter et al. 2007) and suggest tentative placement in subfamily Spiraeoideae, tribe Sorbarieae (Potter et al. 2007). E. Related taxa in region Adenostoma sparsifolium Torrey, known as ribbon-wood or red-shanks is the only other species of Adenostoma in California. It is a much taller, erect to spreading shrub of chaparral vegetation, often 2–6 m tall and has a more restricted distribution than A. fasciculatum. It occurs from San Luis Obispo Co. south into Baja California. Red-shanks produces longer, linear leaves on slender long shoots rather than having leaves clustered on short shoots (lacks "fascicled" leaves). Its bark is cinnamon-colored and in papery layers that sheds in long ribbons. F. Taxonomic issues The Jepson eFlora and the FNA recognize A. f. var. prostratum but the taxon is not recognized by USDA PLANTS (2016). -

Cavitation Resistance Among 26 Chaparral Species of Southern California

Ecological Monographs, 77(1), 2007, pp. 99–115 Ó 2007 by the Ecological Society of America CAVITATION RESISTANCE AMONG 26 CHAPARRAL SPECIES OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA 1,4 2 1 3 ANNA L. JACOBSEN, R. BRANDON PRATT, FRANK W. EWERS, AND STEPHEN D. DAVIS 1Department of Plant Biology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48824-1312 USA 2Department of Biology, California State University, Bakersfield, 14 SCI, 9001 Stockdale Highway, Bakersfield, California 93311 USA 3Natural Science Division, Pepperdine University, 24255 Pacific Coast Highway, Malibu, California 90263 USA Abstract. Resistance to xylem cavitation depends on the size of xylem pit membrane pores and the strength of vessels to resist collapse or, in the case of freezing-induced cavitation, conduit diameter. Altering these traits may impact plant biomechanics or water transport efficiency. The evergreen sclerophyllous shrub species, collectively referred to as chaparral, which dominate much of the mediterranean-type climate region of southern California, have been shown to display high cavitation resistance (pressure potential at 50% loss of hydraulic conductivity; P50). We examined xylem functional and structural traits associated with more negative P50 in stems of 26 chaparral species. We correlated raw-trait values, without phylogenetic consideration, to examine current relationships between P50 and these xylem traits. Additionally, correlations were examined using phylogenetic independent contrasts (PICs) to determine whether evolutionary changes in these xylem traits correlate with changes in P50. Co-occurring chaparral species widely differ in their P50 (À0.9 to À11.0 MPa). Species experiencing the most negative seasonal pressure potential (Pmin) had the highest resistance to xylem cavitation (lowest P50). Decreased P50 was associated with increased xylem density, stem mechanical strength (modulus of rupture), and transverse fiber wall area when both raw values and PICs were analyzed. -

Ceanothus Crassifolius Torrey NRCS CODE: Family: Rhamnaceae (CECR) Order: Rhamnales Subclass: Rosidae Class: Magnoliopsida

I. SPECIES Ceanothus crassifolius Torrey NRCS CODE: Family: Rhamnaceae (CECR) Order: Rhamnales Subclass: Rosidae Class: Magnoliopsida Lower right: Ripening fruits, two already dehisced. Lower center: Longitudinal channeling in stems of old specimen, typical of obligate seeding Ceanothus (>25 yr since last fire). Note dark hypanthium in center of white flowers. Photos by A. Montalvo. A. Subspecific taxa 1. C. crassifolius Torr. var. crassifolius 2. C. crassifolius Torr. var. planus Abrams (there is no NRCS code for this taxon) B. Synonyms 1. C. verrucosus Nuttal var. crassifolius K. Brandegee (Munz & Keck 1968; Burge et al. 2013) 2. C. crassifolius (in part, USDA PLANTS 2019) C. Common name 1. hoaryleaf ceanothus, sometimes called thickleaf ceanothus or thickleaf wild lilac (Painter 2016) 2. same as above; flat-leaf hoary ceanothus and flat-leaf snowball ceanothus are applied to other taxa (Painter 2016) D. Taxonomic relationships Ceanothus is a diverse genus with over 50 taxa that cluster in to two subgenera. C. crassifolius has long been recognized as part of the Cerastes group of Ceanothus based on morphology, life-history, and crossing studies (McMinn 1939a, Nobs 1963). In phylogenetic analyses based on RNA and chloroplast DNA, Hardig et al. (2000) found C. crassifolius clustered into the Cerastes group and in each analysis shared a clade with C. ophiochilus. In molecular and morphological analyses, Burge et al. (2011) also found C. crassifolius clustered into Cerastes. Cerastes included over 20 taxa and numerous subtaxa in both studies. Eight Cerastes taxa occur in southern California (see I. E. Related taxa in region). E. Related taxa in region In southern California, the related Cerastes taxa include: C. -

Conservation Issues: California Chaparral

Author's personal copy Conservation Issues: California Chaparral RW Halsey, California Chaparral Institute, Escondido, CA, United States JE Keeley, U.S. Geological Survey, Three Rivers, CA, United States ã 2016 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. What Is Chaparral? 1 California Chaparral Biodiversity 1 Chaparral Community Types 1 Measuring Chaparral Biodiversity 4 Diversity Within Individual Plant Taxa 5 Faunal Diversity 5 Influence of Geology 7 Influence of Climate 7 Influence of Fire 8 Impact of Climate Change 10 Preserving Chaparral Biodiversity 10 References 10 What Is Chaparral? Chaparral is a diverse, sclerophyllous shrub-dominated plant community shaped by a Mediterranean-type climate (hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters), a complex mixture of relatively young soils (Specht and Moll, 1983), and large, infrequent, high-intensity fires (30–150 year fire return interval) (Keeley and Zedler, 2009; Keeley et al., 2004; Lombardo et al., 2009). Large expanses of dense chaparral vegetation cover coastal mesas, canyons, foothills, and mountain slopes throughout the California Floristic Province (Figure 1), southward into Baja California, and extending north into the Rogue River Valley of southwest Oregon. Disjunct patches of chaparral can also be found in central and southeastern Arizona and northern Mexico (Keeley, 2000). Along with the four other Mediterranean-type climate regions of the world with similar shrubland vegetation (Central Chile, Mediterranean Basin, South Africa, and southwestern Australia) (Table 1), California has been designated a biodiversity hot spot (Myers et al., 2000). Twenty-five designated locations in all, these hot spots have exceptional concentrations of endemic species that are undergoing exceptional loss of habitat (Myers et al., 2000; Rundel, 2004). -

Oak Woodlands and Chaparral

Oak Woodlands and Chaparral Aligning chaparral-associated bird needs with oak woodland restoration and fuel reduction in southwest Oregon and northern California Why conservation is needed Oak woodland habitat in southwest Oregon and northern California is comprised of a vegetation gradient that includes oak savanna, open oak woodlands with grass or chaparral understory, closed canopy oak woodlands, and oak conifer forests. Oak habitats are at risk due to development, encroachment of coniferous forest, invasion of exotic species, and lack of oak regeneration. Birds and other wildlife that depend on these ecosystems have been negatively affected by habitat threats. Photo by Jaime Stephens What is chaparral and why is it important for birds? “Chaparral” is a short, shrubby vegetation type that can be composed of a variety of plant species. In this region, chaparral habitat is often associated with oak woodlands. Chaparral is a natural part of oak habitats, but it also poses a risk of spreading severe fire which can put large, old oak trees at risk. Because oak woodlands are threatened by loss and degradation, management initiatives sometimes reduce chaparral to reduce the risk of high severity fire and promote a mix of low to moderate severity fire. Still, functioning oak woodland mosaics in southern Oregon need many types of vegetation cover, including patches of chaparral. Restoring and managing oak woodland ecosystems in this region requires learning how to best achieve a balanced vegetation composition that includes chaparral habitat components. KBO, in partnership with the Klamath Siskiyou Oak Network, has conducted studies to determine how we might best manage oak and chaparral habitat for bird species. -

Drought-Tolerant and Native Plants for Goleta and Santa Barbara County’S Mediterranean Climate

Drought-Tolerant and Native Plants for Goleta and Santa Barbara County’s Mediterranean Climate Drought tolerant plants for the Santa Barbara and Goleta area. In the 1500's California went through an 80 year drought. During the winter there were blizzards in Central California, the Salinas River froze solid where it flowed into the Monterey Bay. During the summer there was no humidity, no rain, and temperatures in the hundreds for many months. During one year in the 1840's there was no measurable rain in Santa Barbara. (The highest measured rainfall in an hour also was in Southern California, 11 inches in an hour) The same native plants that lived through that are still on the hillsides of California. California native plants that do not normally live in the creeks and ponds are very drought tolerant. The best way to find your plant is to check www.mynativeplants.com and do not water at all. But if you want a simple list of drought tolerant plants that can work for your garden here are some. Adenostoma fasciculatum, Chamise. Adenostoma sparsifolium, Red Shanks Agave deserti, Desert Agave Agave shawii, Coastal Agave Agave utahensis, Century Plant Antirrhinum multiflorum, Multiflowered Snapdragon Arctostaphylos La Panza, Grey Manzanita Arctostaphylos densiflora Sentinel Manzanita Arctostaphylos glandulosa adamsii, Laguna Manzanita. Arctostaphylos crustacea eastwoodiana, Harris Grade manzanita. Arctostaphylos glandulosa zacaensis, San Marcos Manzanita Arctostaphylos glauca, Big Berry Manzanita. Arctostaphylos glauca, Ramona Manzanita Arctostaphylos glauca-glandulosa, Weird Manzanita. 1 | Page Arctostaphylos pungens, Mexican Manzanita Arctostaphylos refugioensis Refugio Manzanita Aristida purpurea, Purple 3-awn Artemisia californica, California Sagebrush Artemisia douglasiana, Mugwort Artemisia ludoviciana, White Sagebrush Asclepias fascicularis, Narrowleaf Milkweed Astragalus trichopodus, Southern California Locoweed Atriplex lentiformis Breweri, Brewers Salt Bush. -

Grow Native Nursery Inventory

Grow Native Nursery Inventory As of Dec 21, 2020 Quantity Scientific Name Common Name Size Available Price Acalypha californica California Copperleaf 4 In 3 $ 6.00 Achillea millefolium 'Sonoma Coast' Sonoma Coast Yarrow 1 Gal 10 $ 10.00 Adenostoma fasciculatum Chamise 1 Gal 10 $ 12.00 Agave sebastiana 'Dwarf Form' Small Form Sebastian's Agave 3 Gal 1 $ 45.00 Agave sebastiana 'Dwarf Form' Small Form Sebastian's Agave 4 In 1 $ 28.00 Alnus rhombifolia White Alder 1 Gal 4 $ 12.00 Aloysia wrightii Oreganillo 1 Gal 3 $ 12.00 Aquilegia formosa Western Columbine 4 In 9 $ 6.00 Arctostaphylos 'Austin Griffiths' Austin Griffiths' Manzanita 1 Gal 11 $ 12.00 Arctostaphylos 'Byrd Hill' Byrd Hill's Manzanita 5 Gal 4 $ 45.00 Arctostaphylos 'Dr. Hurd' Dr. Hurd Manzanita 1 Gal 6 $ 12.00 Arctostaphylos edmundsii 'Bert Johnson' Bert Johnson's Manzanita 1 Gal 15 $ 12.00 Arctostaphylos edmundsii 'Carmel Sur' Carmel Sur Manzanita 4 In 23 $ 6.00 Arctostaphylos glauca Bigberry Manzanita 1 Gal 6 $ 15.00 Arctostaphylos 'Howard Mcminn' Howard McMinn's Manzanita 1 Gal 7 $ 12.00 Arctostaphylos 'Howard Mcminn' Howard McMinn's Manzanita 1 Gal 2 $ 12.00 Arctostaphylos 'Lester Rowntree' Lester Rowntree's Manzanita 1 Gal 11 $ 12.00 Arctostaphylos morroensis Morro Bay Manzanita 1 Gal 3 $ 12.00 Arctostaphylos 'Pacific Mist' Pacific Mist Manzanita 1 Gal 29 $ 12.00 Default Arctostaphylos 'Pt. Reyes' Point Reyes Manzanita Title 10 $ 12.00 Arctostaphylos refugioensis Refugio Manzanita 3 Gal 1 $ 26.00 Arctostaphylos refugioensis Refugio Manzanita 1 Gal 15 $ 12.00 Arctostaphylos -

Vascular Flora of the Liebre Mountains, Western Transverse Ranges, California Steve Boyd Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 18 | Issue 2 Article 15 1999 Vascular flora of the Liebre Mountains, western Transverse Ranges, California Steve Boyd Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Boyd, Steve (1999) "Vascular flora of the Liebre Mountains, western Transverse Ranges, California," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 18: Iss. 2, Article 15. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol18/iss2/15 Aliso, 18(2), pp. 93-139 © 1999, by The Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, Claremont, CA 91711-3157 VASCULAR FLORA OF THE LIEBRE MOUNTAINS, WESTERN TRANSVERSE RANGES, CALIFORNIA STEVE BOYD Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden 1500 N. College Avenue Claremont, Calif. 91711 ABSTRACT The Liebre Mountains form a discrete unit of the Transverse Ranges of southern California. Geo graphically, the range is transitional to the San Gabriel Mountains, Inner Coast Ranges, Tehachapi Mountains, and Mojave Desert. A total of 1010 vascular plant taxa was recorded from the range, representing 104 families and 400 genera. The ratio of native vs. nonnative elements of the flora is 4:1, similar to that documented in other areas of cismontane southern California. The range is note worthy for the diversity of Quercus and oak-dominated vegetation. A total of 32 sensitive plant taxa (rare, threatened or endangered) was recorded from the range. Key words: Liebre Mountains, Transverse Ranges, southern California, flora, sensitive plants. INTRODUCTION belt and Peirson's (1935) handbook of trees and shrubs. Published documentation of the San Bernar The Transverse Ranges are one of southern Califor dino Mountains is little better, limited to Parish's nia's most prominent physiographic features. -

Flora and Ecology of the Santa Monica Mountains Edited by D.A

Flora and Ecology of the Santa Monica Mountains Edited by D.A. Knapp. 2007. Southern California Botanists, Fullerton, CA. 159 FREEZING TOLERANCE IMPACTS CHAPARRAL SPECIES DISTRIBUTION IN THE SANTA MONICA MOUNTAINS Stephen D. Davis1, R. Brandon Pratt2, Frank W. Ewers3, and Anna L. Jacobsen4 1Natural Science Division Pepperdine University, Malibu, CA 90263 [email protected]. 2Department of Biology California State University, Bakersfield Bakersfield, CA 93311 [email protected] 3Biological Sciences Department California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Pomona, CA 91768 [email protected] 4Michigan State University Department of Plant Biology East Lansing, MI 48824 [email protected] ABSTRACT: A shift in chaparral species composition occurs from coastal to inland sites of the Santa Monica Mountains of southern California. Past studies have attributed this pattern to differential adaptations of chaparral species to gradients in moisture and solar radiation. We examined an alternate hypothesis, that shifts in species composition from coastal to inland sites is a result of differential response to freezing and the interactions of freezing with drought. Coastal sites rarely experience air temperatures below 0 °C whereas just 5 to 6 km inland, cold valleys experience temperatures as low as -12 °C. Seasonal drought can last 6 to 8 months and may extend, on rare occasions, into the month of December, coincidental with the onset of winter freeze. Either water stress or freezing, by independent mechanisms, can induce embolism in stem xylem and block water transport from soil to leaves, leading to branchlet dieback or whole shoot death. Water stress in combination with freezing may enhance xylem embolism formation. Post- fire seedlings are especially vulnerable because of greater tissue sensitivity to freezing injury, diminutive roots that preclude access to deep soil moisture or resprout success, and greater exposure to nighttime radiation freezes after canopy removal by fire.