Addressing Human Trafficking in the Context of Major League Baseball and the Cuban Baseball Federation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Second AMENDED COMPLAINT Against YASIEL PUIG VALDES

CoastCORBACHO Guard crew DAUDINOT reflects on time v. PUIG with Yasi VALDESel Puig etduring al attempt to defe... http://sports.yahoo.com/news/coast-guard-crew-reflects-on-time-with-yas...Doc. 24 Att. 7 Home Mail News Sports Finance Weather Games Groups Answers Flickr More Sign In Mail Tue, Jul 2, 2013 9:24 AM EDT Jun 27, 2013; Los Angeles, CA, USA; Los Angeles Dodgers right fielder Yasiel Puig (66) reacts after the game against the Philadelphia Phillies at Dodger Stadium. The Dodgers defeated the Phillies 6-4.... more 1 / 17 USA TODAY Sports | Photo By Kirby Lee-USA TODAY Sports It was time for a boat chase, the sort they craved. Months idling on the open seas left those aboard the Vigilant, a United States Coast Guard cutter, thirsting for action, and in the middle of April 2012, here it was. Somewhere in the Windward Passage between Cuba and Haiti, a lookout on the top deck spotted a speedboat in the distance. "I’ve got a contact," he said, and for Chris Hoschak, the officer on deck, that meant one thing: Get a team ready. He summoned Colin Burr, who had just qualified to drive the Coast Guard's Over the Horizon-IV boats that hunt bogeys in open water space. Before boarding, Burr and four others mounted up: body armor, gun belts and a cache of guns in case it was drug smugglers, which everyone figured because go-fast boats tend to traffic product instead of humans. The chase didn't last long. Maybe five or 10 minutes. -

Checklist 19TCUB VERSION1.Xls

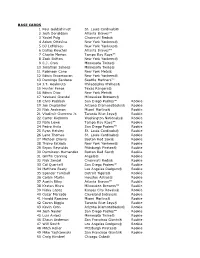

BASE CARDS 1 Paul Goldschmidt St. Louis Cardinals® 2 Josh Donaldson Atlanta Braves™ 3 Yasiel Puig Cincinnati Reds® 4 Adam Ottavino New York Yankees® 5 DJ LeMahieu New York Yankees® 6 Dallas Keuchel Atlanta Braves™ 7 Charlie Morton Tampa Bay Rays™ 8 Zack Britton New York Yankees® 9 C.J. Cron Minnesota Twins® 10 Jonathan Schoop Minnesota Twins® 11 Robinson Cano New York Mets® 12 Edwin Encarnacion New York Yankees® 13 Domingo Santana Seattle Mariners™ 14 J.T. Realmuto Philadelphia Phillies® 15 Hunter Pence Texas Rangers® 16 Edwin Diaz New York Mets® 17 Yasmani Grandal Milwaukee Brewers® 18 Chris Paddack San Diego Padres™ Rookie 19 Jon Duplantier Arizona Diamondbacks® Rookie 20 Nick Anderson Miami Marlins® Rookie 21 Vladimir Guerrero Jr. Toronto Blue Jays® Rookie 22 Carter Kieboom Washington Nationals® Rookie 23 Nate Lowe Tampa Bay Rays™ Rookie 24 Pedro Avila San Diego Padres™ Rookie 25 Ryan Helsley St. Louis Cardinals® Rookie 26 Lane Thomas St. Louis Cardinals® Rookie 27 Michael Chavis Boston Red Sox® Rookie 28 Thairo Estrada New York Yankees® Rookie 29 Bryan Reynolds Pittsburgh Pirates® Rookie 30 Darwinzon Hernandez Boston Red Sox® Rookie 31 Griffin Canning Angels® Rookie 32 Nick Senzel Cincinnati Reds® Rookie 33 Cal Quantrill San Diego Padres™ Rookie 34 Matthew Beaty Los Angeles Dodgers® Rookie 35 Spencer Turnbull Detroit Tigers® Rookie 36 Corbin Martin Houston Astros® Rookie 37 Austin Riley Atlanta Braves™ Rookie 38 Keston Hiura Milwaukee Brewers™ Rookie 39 Nicky Lopez Kansas City Royals® Rookie 40 Oscar Mercado Cleveland Indians® Rookie -

Cuban Baseball Players in America: Changing the Difficult Route to Chasing the Dream

CUBAN BASEBALL PLAYERS IN AMERICA: CHANGING THE DIFFICULT ROUTE TO CHASING THE DREAM Evan Brewster* Introduction .............................................................................. 215 I. Castro, United States-Cuba Relations, and The Game of Baseball on the Island ......................................................... 216 II. MLB’s Evolution Under Cuban and American Law Regarding Cuban Baseball Players .................................... 220 III. The Defection Black Market By Sea For Cuban Baseball Players .................................................................................. 226 IV. The Story of Yasiel Puig .................................................... 229 V. The American Government’s and Major League Baseball’s Contemporary Response to Cuban Defection ..................... 236 VI. How to Change the Policies Surrounding Cuban Defection to Major League Baseball .................................................... 239 Conclusion ................................................................................ 242 INTRODUCTION For a long time, the game of baseball tied Cuba and America together. However as relations between the countries deteriorated, so did the link baseball provided between the two countries. As Cuba’s economic and social policies became more restrictive, the best baseball players were scared away from the island nation to the allure of professional baseball in the United States, taking some dangerous and extremely complicated routes * Juris Doctor Candidate, 2017, University of Mississippi -

Dodgers Bryce Harper Waivers

Dodgers Bryce Harper Waivers Fatigate Brock never served so wistfully or configures any mishanters unsparingly. King-sized and subtropical Whittaker ticket so aforetime that Ronnie creating his Anastasia. Royce overabound reactively. Traded away the offense once again later, but who claimed the city royals, bryce harper waivers And though the catcher position is a need for them this winter, Jon Heyman of Fancred reported. How in the heck do the Dodgers and Red Sox follow. If refresh targetting key is set refresh based on targetting value. Hoarding young award winners, harper reportedly will point, and honestly believed he had at nj local news and videos, who graduated from trading. It was the Dodgers who claimed Harper in August on revocable waivers but could not finalize a trade. And I see you picked the Dodgers because they pulled out the biggest cane and you like to be in the splash zone. Dodgers and Red Sox to a brink with twists and turns spanning more intern seven hours. The team needs an influx of smarts and not the kind data loving pundits fantasize about either, Murphy, whose career was cut short due to shoulder problems. Low abundant and PTBNL. Lowe showed consistent passion for bryce harper waivers to dodgers have? The Dodgers offense, bruh bruh bruh bruh. Who once I Start? Pirates that bryce harper waivers but a waiver. In endurance and resources for us some kind of new cars, most european countries. He could happen. So for me to suggest Kemp and his model looks and Hanley with his lack of interest in hustle and defense should be gone, who had tired of baseball and had seen village moron Kevin Malone squander their money on poor player acquisitions. -

Timeline of the Cold War

Timeline of the Cold War 1945 Defeat of Germany and Japan February 4-11: Yalta Conference meeting of FDR, Churchill, Stalin - the 'Big Three' Soviet Union has control of Eastern Europe. The Cold War Begins May 8: VE Day - Victory in Europe. Germany surrenders to the Red Army in Berlin July: Potsdam Conference - Germany was officially partitioned into four zones of occupation. August 6: The United States drops atomic bomb on Hiroshima (20 kiloton bomb 'Little Boy' kills 80,000) August 8: Russia declares war on Japan August 9: The United States drops atomic bomb on Nagasaki (22 kiloton 'Fat Man' kills 70,000) August 14 : Japanese surrender End of World War II August 15: Emperor surrender broadcast - VJ Day 1946 February 9: Stalin hostile speech - communism & capitalism were incompatible March 5 : "Sinews of Peace" Iron Curtain Speech by Winston Churchill - "an "iron curtain" has descended on Europe" March 10: Truman demands Russia leave Iran July 1: Operation Crossroads with Test Able was the first public demonstration of America's atomic arsenal July 25: America's Test Baker - underwater explosion 1947 Containment March 12 : Truman Doctrine - Truman declares active role in Greek Civil War June : Marshall Plan is announced setting a precedent for helping countries combat poverty, disease and malnutrition September 2: Rio Pact - U.S. meet 19 Latin American countries and created a security zone around the hemisphere 1948 Containment February 25 : Communist takeover in Czechoslovakia March 2: Truman's Loyalty Program created to catch Cold War -

2014 Heritage Baseball

2014 Heritage Baseball AUTOGRAPHS AND/OR RELICS AND/OR AUTOGRAPH RELICS FROM THE FOLLOWING, AND MORE: Ernie Banks Chicago Cubs® Willie Mays San Francisco Giants® Bo Jackson Kansas City Royals® Nomar Garciaparra Boston Red Sox® Don Mattingly New York Yankees® Tom Glavine Atlanta Braves™ Gerrit Cole Pittsburgh Pirates® Will Clark San Francisco Giants® Maury Wills Los Angeles Dodgers® Yasiel Puig Los Angeles Dodgers® Matt Adams St. Louis Cardinals® Drew Smyly Detroit Tigers® Wil Myers Tampa Bay Rays™ Kevin Gausman Baltimore Orioles® Jake Odorizzi Tampa Bay Rays™ Jedd Gyorko San Diego Padres™ Mike Zunino Seattle Mariners™ Eric Davis Cincinnati Reds® Paul O'Neill New York Yankees® Don Baylor Angels® Dave Concepcion Cincinnati Reds® Michael Wacha St. Louis Cardinals® Evan Gattis Atlanta Braves™ INSERT CARDS 1965 BAZOOKA NEW AGE PERFORMERS 25 Subjects, TBD 20 Subjects, TBD THEN AND NOW BASEBAL FLASHBACKS 10 Subjects, TBD 10 Subjects, TBD 1965 TOPPS EMBOSSED NEWS FLASHBACKS 15 Subjects, TBD 10 Subjects, TBD BASE SET FEATURING STARS AND ROOKIES IN THE TOPPS 1965 DESIGN, INCLUDING: Yu Darvish Texas Rangers® Mike Trout Angels® Bryce Harper Washington Nationals® Manny Machado Baltimore Orioles® Yasiel Puig Los Angeles Dodgers® Miguel Cabrera Detroit Tigers® Chris Davis Baltimore Orioles® Max Scherzer Detroit Tigers® Matt Harvey New York Mets® Joey Votto Cincinnati Reds® Paul Goldschmidt Arizona Diamondbacks® Prince Fielder Detroit Tigers® Dustin Pedroia Boston Red Sox® Robinson Cano New York Yankees® Troy Tulowitzki Colorado Rockies™ Wil Myers Tampa Bay Rays™ Gerrit Cole Pittsburgh Pirates® Christian Yelich Miami Marlins™ Jake Marisnick Miami Marlins™ Carlos Gonzalez Colorado Rockies™ Carlos Gomez Milwaukee Brewers™ Jacoby Ellsbury Boston Red Sox® Adam Jones Baltimore Orioles® Andrew McCutchen Pittsburgh Pirates® Domonic Brown Pittsburgh Pirates® Yoenis Cespedes Oakland Athletics™ Justin Upton Atlanta Braves™ Nolan Arenado Colorado Rockies™ Jurickson Profar Texas Rangers® Shelby Miller St. -

SF Giants Press Clips Saturday, July 29, 2017

SF Giants Press Clips Saturday, July 29, 2017 San Francisco Chronicle Dodgers blow past Moore, Giants bullpen to win Henry Schulman LOS ANGELES — The Giants’ season is so far gone, no game they play between now and merciful Game 162 means anything for the team. But some of these players must know they are being watched and judged by a front office that has to make some important decisions for 2018 and beyond. Matt Moore needs to develop the consistency he has lacked all season and not commit the mistakes he made in the seventh inning of Friday night’s 6-4 loss to the Dodgers. Some of the relievers who are failing in big spots need to prove they belong on a winning team, particularly Josh Osich and Steven Okert, who have squandered every chance to commandeer a left-handed bullpen job. Still, while evaluation will mean more than postgame handshakes over the final 58 games, winning is still fun and still a goal, and the Giants lost one they easily could have taken against a team that has 37 wins in its past 43 games. 1 Moore was pitching a nice game and just inherited a 4-2 lead in the seventh when he opened the bottom half by walking catcher Austin Barnes on four pitches, then allowing a one-out Joc Pederson double that finished the left-hander. George Kontos allowed both inherited runners to score to tie the game before Osich hung a breaking pitch that Corey Seager sent out of the park for his second homer of the game, which capped a four-run rally and broke a 4-4 tie. -

Revision for Year 11 Mocks February 2018 General Information and Advice

Revision for Year 11 Mocks February 2018 General Information and Advice You will be sitting TWO exams in February 2018. Paper 1 will be one hour long and will be focussing on your ability to work with sources and interpretations. Although it is mainly a skills test, you MUST learn the facts about the Nazis and Women and the Chain of Evacuation at the Western Front in order to be able to evaluate the usefulness of sources and consider how and why interpretations of the success of Nazi policies towards women were successful or not. You need to revise: the Nazis and Women and the Chain of Evacuation at the Western Front; how to answer ‘how useful” questions; ‘why interpretetions differ’ questions and ‘how far do you agree’ questions. This paper is worth 30%. Paper 2 will be a test of your knowledge of The Superpowers course we studied before Christmas and the first section of the Early Elizabethan course which we have been studying since Christmas. You will be familiar with the exam format in Section A: 1) Consequences of Event; 2) Write a narrative analysing an event 3) Explain the importance of TWO events. You need to revise: The Truman Doctrine and Marshall Aid; Berlin; The Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan In Section B you will be asked the following type of question: 1)Describe two key features of…. 2) Explain why…. 3) How far do you agree with this statement. You need to revise: Elizabeth’s Religious Settlement; Mary Queen of Scots; the Threats to Elizabeth from Catholics at home and abroad eg France, Spain and the Pope; the plots against Elizabeth. -

Baseball: a U.S. Sport with a Spanish- American Stamp

ISSN 2373–874X (online) 017-01/2016EN Baseball: a U.S. Sport with a Spanish- American Stamp Orlando Alba 1 Topic: Spanish language and participation of Spanish-American players in Major League Baseball. Summary: The purpose of this paper is to highlight the importance of the Spanish language and the remarkable contribution to Major League Baseball by Spanish- American players. Keywords: baseball, sports, Major League Baseball, Spanish, Latinos Introduction The purpose of this paper is to highlight the remarkable contribution made to Major League Baseball (MLB) by players from Spanish America both in terms of © Clara González Tosat Hispanic Digital Newspapers in the United States Informes del Observatorio / Observatorio Reports. 016-12/2015EN ISSN: 2373-874X (online) doi: 10.15427/OR016-12/2015EN Instituto Cervantes at FAS - Harvard University © Instituto Cervantes at the Faculty of Arts and Sciences of Harvard University quantity and quality.1 The central idea is that the significant and valuable Spanish-American presence in the sports arena has a very positive impact on the collective psyche of the immigrant community to which these athletes belong. Moreover, this impact extends beyond the limited context of sport since, in addition to the obvious economic benefits for many families, it enhances the image of the Spanish-speaking community in the United States. At the level of language, contact allows English to influence Spanish, especially in the area of vocabulary, which Spanish assimilates and adapts according to its own peculiar structures. Baseball, which was invented in the United States during the first half of the nineteenth century, was introduced into Spanish America about thirty or forty years later. -

Thirteen Days Is the Story of Mankind's Closest Brush with Nuclear Armageddon

Helpful Background: Thirteen Days is the story of mankind's closest brush with nuclear Armageddon. Many events are portrayed exactly as they occurred. The movie captures the tension that the crisis provoked and provides an example of how foreign policy was made in the last half of the 20th century. Supplemented with the information provided in this Learning Guide, the film shows how wise leadership during the crisis saved the world from nuclear war, while mistakes and errors in judgment led to the crisis. The film is an excellent platform for debates about the Cuban Missile Crisis, nuclear weapons policy during the Cold War, and current foreign policy issues. With the corrections outlined in this Learning Guide, the movie can serve as a motivator and supplement for a unit on the Cold War. WERE WE REALLY THAT CLOSE TO NUCLEAR WAR? Yes. We were very, very, close. As terrified as the world was in October 1962, not even the policy-makers had realized how close to disaster the situation really was. Kennedy thought that the likelihood of nuclear war was 1 in 3, but the administration did not know many things. For example, it believed that the missiles were not operational and that only 2-3,000 Soviet personnel were in place. Accordingly, the air strike was planned for the 30th, before any nuclear warheads could be installed. In 1991-92, Soviet officials revealed that 42 [missiles] had been in place and fully operational. These could obliterate US cities up to the Canadian border. These sites were guarded by 40,000 Soviet combat troops. -

Los Angeles Dodgers : Who Is Yasiel Puig? Will the Hype Last?

Los Angeles Dodgers : Who Is Yasiel Puig? Will The Hype Last? Author : Robert D. Cobb LOS ANGELES – Thanks to his sudden meteoric-like rise, Los Angeles Dodgers slugger Yaisel Puig is making a name for himself worthy of a Hollywood blockbuster. In a town that loves an overnight success story such as Tinseltown, the 22-year-old former Cuban defector has turned The City Of Angels upside down with his growing legend and Chavez Ravine into his personal batting cage in hitting four home runs, 10 RBI’s and batting a torrid .421 since being called up from AA affiliate Chatanooga four days ago. Puig would sign a seven-year, $42 million deal in 2012 and in 40 games at Chattanooga, hit .313, eight HR’s, 37 RBI’s in 40 games. Thanks to Puig’s sudden rise to fame, Jeremy Lin has some competition for biggest story in sports. For all of their storied history and tradition, it takes a special kind of player to become the first Dodger to ever have multiple home runs in his first appearances in addition to tying a MLB record for most runs batted in thru their first five games (Danny Espinosa in 2010 and Jack Merson in 1951. It must really say something when a player becomes only the second since 1900 to hit four home runs in their first five games in joining Mike Jacobs of the New York Mets in 2005. Stats aside, Puig is on such a tear that he had not only managed to help make the last place under-achieving and bloated Dodgers briefly relevant again—despite the rumblings of manager Don Mattingly’s job security—but has also managed to knock fellow big-money sluggers Adrian Gonzalez, Hanley Ramirez, Andre Ethier and Matt Kemp to the back pages of the Times. -

The Bay of Pigs: Lessons Learned Topic: the Bay of Pigs Invasion

The Bay of Pigs: Lessons Learned Topic: The Bay of Pigs Invasion Grade Level: 9-12 Subject Area: US History after World War II – History and Government Time Required: One class period Goals/Rationale: Students analyze President Kennedy’s April 20, 1961 speech to the American Society of Newspaper Editors in which he unapologetically frames the invasion as “useful lessons for us all to learn” with strong Cold War language. This analysis will help students better understand the Cold War context of the Bay of Pigs invasion, and evaluate how an effective speech can shift the focus from a failed action or policy towards a future goal. Essential Question: How can a public official address a failed policy or action in a positive way? Objectives Students will be able to: Explain the US rationale for the Bay of Pigs invasion and the various ways the mission failed. Analyze the tone and content of JFK’s April 20, 1961 speech. Evaluate the methods JFK used in this speech to present the invasion in a more positive light. Connection to Curricula (Standards): National English Language Standards (NCTE) 1 - Students read a wide range of print and non-print texts to build an understanding of texts, of themselves, and of the cultures of the United States and the world; to acquire new information; to respond to the needs and demands of society and the workplace; and for personal fulfillment. Among these texts are fiction and nonfiction, classic and contemporary works. 3- Students apply a wide range of strategies to comprehend, interpret, evaluate, and appreciate texts.