Out of Passivity: Potential Role of OFDI in IFDI-Based Learning Trajectory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Beijing Auto Show 2010 - Carazoo.Com

Apr 26, 2010 16:01 IST The Beijing Auto Show 2010 - Carazoo.com The Beijing Auto Show 2010 has already begun and we bring to you the latest info from the auto show. There were around 2,100 companies from 16 nations and regions exhibiting their products. Today is the day. Yes, today, the event is open to the press. The auto exhibition area's 200,000 square meters are literally adorned with cars, including plenty of concept cars. A new variant of the Mercedes-Benz E-Class will be launched after this China auto show in Beijing. Car makers have already begun targeting emerging markets like Brazil and India. How can China be left behind? The new vehicle launches have already begun at the Beijing auto show in a race to capture China's fast-growing market among loose sales elsewhere. Till around 1995, there were hardly any private cars in China. But now, the scenario is different. The explosive sales growth in the emerging markets has become the highest. Watching the new long-wheelbase sedans from leading luxury brands like Audi and BMW at the Auto Show 2010 is sure going to be a treat to the eyes. An all-new high-powered Ferrari 599 GTO and a V6- powered Porsche Panamera are also going to add excitement. Lamborghini is all set to showcase the special model that it has made exclusively for the Chinese market. Ford is not going to stay behind. It will present its all-new global concept that could be sold in China, Europe or the US. -

SAIC MOTOR CORPORATION LIMITED Annual Report 2016

SAIC MOTOR ANNUAL REPORT 2016 Company Code:600104 Abbreviation of Company: SAIC SAIC MOTOR CORPORATION LIMITED Annual Report 2016 Important Note 1. Board of directors (the "Board"), board of supervisors, directors, supervisors and senior management of the Company certify that this report does not contain any false or misleading statements or material omissions and are jointly and severally liable for the authenticity, accuracy and integrity of the content. 2. All directors attended Board meetings. 3. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Certified Public Accountants LLP issued standard unqualified audit report for the Company. 4. Mr. Chen Hong, Chairman of the Board, Mr. Wei Yong, the chief financial officer, and Ms. Gu Xiao Qiong. Head of Accounting Department, certify the authenticity, accuracy and integrity of the financial statements contained in the annual report of the current year. 5. Plan of profit distribution or capital reserve capitalization approved by the Board The Company plans to distribute cash dividends of RMB 16.50 (inclusive of tax) per 10 shares, amounting to RMB 19,277,711,252.25 in total based on total shares of 11,683,461,365. The Company has no plan of capitalization of capital reserve this year. The cash dividend distribution for the recent three years accumulates to RMB48,605,718,485.39 in total (including the year of 2016). 6. Risk statement of forward-looking description √Applicable □N/A The forward-looking description on future plan and development strategy in this report does not constitute substantive commitment to investors. Please note the investment risk. 7. Does the situation exist where the controlling shareholders and their related parties occupy the funds of the Company for non-operational use? No. -

Competing in the Global Truck Industry Emerging Markets Spotlight

KPMG INTERNATIONAL Competing in the Global Truck Industry Emerging Markets Spotlight Challenges and future winning strategies September 2011 kpmg.com ii | Competing in the Global Truck Industry – Emerging Markets Spotlight Acknowledgements We would like to express our special thanks to the Institut für Automobilwirtschaft (Institute for Automotive Research) under the lead of Prof. Dr. Willi Diez for its longstanding cooperation and valuable contribution to this study. Prof. Dr. Willi Diez Director Institut für Automobilwirtschaft (IfA) [Institute for Automotive Research] [email protected] www.ifa-info.de We would also like to thank deeply the following senior executives who participated in in-depth interviews to provide further insight: (Listed alphabetically by organization name) Shen Yang Senior Director of Strategy and Development Beiqi Foton Motor Co., Ltd. (China) Andreas Renschler Member of the Board and Head of Daimler Trucks Division Daimler AG (Germany) Ashot Aroutunyan Director of Marketing and Advertising KAMAZ OAO (Russia) Prof. Dr.-Ing. Heinz Junker Chairman of the Management Board MAHLE Group (Germany) Dee Kapur President of the Truck Group Navistar International Corporation (USA) Jack Allen President of the North American Truck Group Navistar International Corporation (USA) George Kapitelli Vice President SAIC GM Wuling Automobile Co., Ltd. (SGMW) (China) Ravi Pisharody President (Commercial Vehicle Business Unit) Tata Motors Ltd. (India) © 2011 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. Member firms of the KPMG network of independent firms are affiliated with KPMG International. KPMG International provides no client services. All rights reserved. Competing in the Global Truck Industry – Emerging Markets Spotlight | iii Editorial Commercial vehicle sales are spurred by far exceeded the most optimistic on by economic growth going in hand expectations – how can we foresee the with the rising demand for the transport potentials and importance of issues of goods. -

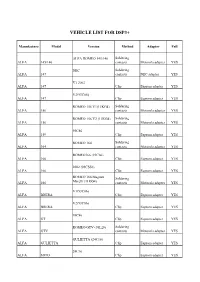

Vehicle List for Dsp3+

VEHICLE LIST FOR DSP3+ Manufacture Model Version Method Adapter Full ALFA ROMEO 145\146 Soldering ALFA 145\146 contacts Motorola adapter YES NEC Soldering ALFA 147 contacts NEC adapter YES V1 2002 ALFA 147 Clip Eeprom adapter YES V2(93C86) ALFA 147 Clip Eeprom adapter YES ROMEO 156 V1(11KG4) Soldering ALFA 156 contacts Motorola adapter YES ROMEO 156 V2 (11KG4) Soldering ALFA 156 contacts Motorola adapter YES 93C86 ALFA 159 Clip Eeprom adapter YES ROMEO 164 Soldering ALFA 164 contacts Motorola adapter YES ROMEO166 (93C66) ALFA 166 Clip Eeprom adapter YES 2002 (93CS56) ALFA 166 Clip Eeprom adapter YES ROMEO 166 Magneti Soldering ALFA 166 Marelli (11KG4) contacts Motorola adapter YES V1(93C86) ALFA BRERA Clip Eeprom adapter YES V2(93C86) ALFA BRERA Clip Eeprom adapter YES 93C86 ALFA GT Clip Eeprom adapter YES ROMEO GTV (05L28) Soldering ALFA GTV contacts Motorola adapter YES GULIETTA (24C16) ALFA GULIETTA Clip Eeprom adapter YES 24C16 ALFA MITO Clip Eeprom adapter YES ROMEO SPIDER (93C86) ALFA SPIDER Clip Eeprom adapter YES ASTON Soldering MATIN DB9 contacts Motorola adapter YES ASTON Soldering MATIN VANTAGE contacts Motorola adapter YES -2001 AUDI A2 clip Eeprom adapter YES 2001- AUDI A2 clip Eeprom adapter YES VDO -2001.7 AUDI A2 Diagnosis-plug OBD adapter YES 07-UP Soldering AUDI A3 contacts JC adapter YES CLEAR EEROR 07-UP AUDI A3 Diagnosis-plug OBD adapter YES 07-UP AUDI A3 Diagnosis-plug OBD adapter YES -2001.7 AUDI A3 Diagnosis-plug OBD adapter YES 2003-2006 AUDI A3 Diagnosis-plug OBD adapter YES MAGNETI MARELLI AUDI A3 Diagnosis-plug -

CHINA FIELD TRIP May 10Th –12Th, 2011

CHINA FIELD TRIP May 10th –12th, 2011 This presentation may contain forward-looking statements. Such forward-looking statements do not constitute forecasts regarding the Company’s results or any other performance indicator, but rather trends or targets, as the case may be. These statements are by their nature subject to risks and uncertainties as described in the Company’s annual report available on its Internet website (www.psa-peugeot-citroen.com). These statements do not reflect future performance of the Company, which may materially differ. The Company does not undertake to provide updates of these statements. More comprehensive information about PSA PEUGEOT CITROËN may be obtained on its Internet website (www.psa-peugeot-citroen.com), under Regulated Information. th th China Field Trip - May 10 –12 , 2011 2 PSA in Asia – Market Forecast, PSA in China: ongoing successes and upsides Frédéric Saint-Geours Executive VP, Finance and Strategic Development Grégoire Olivier, Executive VP, Asia Table of contents Introduction China: the new auto superpower China: a global economic power The world’s largest automotive market The growth story is set to continue PSA in China China: a second home market for PSA 2 complementary JVs Key challenges in China and PSA differentiation factors A sustainable profitable growth Extending the Chinese Success ASEAN strategy Capturing the Indian opportunity th th China Field Trip - May 10 –12 , 2011 4 PSA – a global automotive player (1/2) > 39% of PSA’s 2010 sales are realized outside of Europe, of -

The Role and Characteristics of Chinese State-Owned and Private Enterprises in Overseas Investments

The Role and Characteristics of Chinese State-owned and Private Enterprises in Overseas Investments 1 The Role and Characteristics of Chinese State-owned and Private Enterprises in Overseas Investments Researched and written by Mark Grimsditch Published by Friends of the Earth US, June 2015 ©Copyright Friends of the Earth US Design by Design Action Courtesy of Creative Commons Acknowledgements Friends of the Earth US would like to thank Mark Grimsditch for his work in authoring this report. We also would like to thank our friends and colleagues for their help in reviewing this report, especially Michelle Chan, Economic Policy Director at FOE US. About Friends of the Earth Friends of the Earth U.S., founded by David Brower in 1969, is the U.S. voice of the world’s largest federation of grassroots environmental groups, with a presence in 74 countries. Friends of the Earth works to defend the environment and champion a more healthy and just world. Throughout our 45-year history, we have provided crucial leadership in campaigns resulting in landmark environmental laws, precedent-setting legal victories and groundbreaking reforms of domestic and international regulatory, corporate and financial institution policies.www.FoE.org For more information on this report, please contact: [email protected]. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.......................................................................................................4 Overview of Chinese Enterprises ......................................................................5 State-owned -

Analysis of the Dynamic Relationship Between the Emergence Of

Annals of Business Administrative Science 8 (2009) 21–42 Online ISSN 1347-4456 Print ISSN 1347-4464 Available at www.gbrc.jp ©2009 Global Business Research Center Analysis of the Dynamic Relationship between the Emergence of Independent Chinese Automobile Manufacturers and International Technology Transfer in China’s Auto Industry Zejian LI Manufacturing Management Research Center Faculty of Economics, the University of Tokyo E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This paper examines the relationship between the emergence of independent Chinese automobile manufacturers (ICAMs) and International Technology Transfer. Many scholars indicate that the use of outside supplies is the sole reason for the high-speed growth of ICAMs. However, it is necessary to outline the reasons and factors that might contribute to the process at the company-level. This paper is based on the organizational view. It examines and clarifies the internal dynamics of the ICAMs from a historical perspective. The paper explores the role that international technology transfer has played in the emergence of ICAMs. In conclusion, it is clear that due to direct or indirect spillover from joint ventures, ICAMs were able to autonomously construct the necessary core competitive abilities. Keywords: marketing, international business, multinational corporations (MNCs), technology transfer, Chinese automobile industry but progressive emergence of independent Chinese 1. Introduction automobile manufacturers (ICAMs). It will also The purpose of this study is to investigate -

A Case Study of General Motors and Daewoo กรณีศึกษาของเจนเนอรัลมอเตอรและแดวู History Going Back to 1908

Journal of International Studies, Prince of Songkla University Vol. 6 No. 2:July - December 2016 National Culture and the Challenges in วัฒนธรรมประจำชาติและความทาทายในการจัดการ Relevant Background ownership of another organization. Coyle (2000:2) describes mergers achievements and the many failures remain vague (Stahl, et al, palan & Spreitzer (1997) argue that Strategic change represents a strategy concerns on cost reduction and/or revenue generation posture is collaboration. The negotiation process began in 1972 Figure3 GM-Daewoo Integration Process กลยุทธการเปลี่ยนแปลง General Motors Company (GM) is a world leading car manufacturer as the coming together of two companies of roughly equal size, 2005). The top post deal challenges of M&A are illustrated in the radical organizational change that is consciously initiated by top whereas revolutionary strategy tends to focus both rapid change between Rick Wagoner, CEO of GM and Kim Woo-Choong, CEO of (Ferrell, 2011) Managing Strategic Changes: which is based in Detroit, United States of America, with its long pooling their recourses into a single business. Johnson et al. further figure 1 which data were collected from the survey in 2009 by managers, creating a shift in key activities or structures that goes and organizational culture change. GM and Daewoo was an explicit Daewoo Group. They successfully agreed into a joint venture of A Case Study of General Motors and Daewoo กรณีศึกษาของเจนเนอรัลมอเตอรและแดวู history going back to 1908. It was founded by William C. Durant. argue the motives for M&A typically involve the managers of one KPMG. Apparently complex integration of two businesses is the beyond incremental changes to preexisting processes. Most example (Froese, 2010). -

Report on the Affairs of Phoenix Venture Holdings Limited, Mg Rover Group Limited and 33 Other Companies Volume I

REPORT ON THE AFFAIRS OF PHOENIX VENTURE HOLDINGS LIMITED, MG ROVER GROUP LIMITED AND 33 OTHER COMPANIES VOLUME I Gervase MacGregor FCA Guy Newey QC (Inspectors appointed by the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry under section 432(2) of the Companies Act 1985) Report on the affairs of Phoenix Venture Holdings Limited, MG Rover Group Limited and 33 other companies by Gervase MacGregor FCA and Guy Newey QC (Inspectors appointed by the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry under section 432(2) of the Companies Act 1985) Volume I Published by TSO (The Stationery Office) and available from: Online www.tsoshop.co.uk Mail, Telephone, Fax & E-mail TSO PO Box 29, Norwich, NR3 1GN Telephone orders/General enquiries: 0870 600 5522 Fax orders: 0870 600 5533 E-mail: [email protected] Textphone 0870 240 3701 TSO@Blackwell and other Accredited Agents Customers can also order publications from: TSO Ireland 16 Arthur Street, Belfast BT1 4GD Tel 028 9023 8451 Fax 028 9023 5401 Published with the permission of the Department for Business Innovation and Skills on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown Copyright 2009 All rights reserved. Copyright in the typographical arrangement and design is vested in the Crown. Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to the Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU. First published 2009 ISBN 9780 115155239 Printed in the United Kingdom by the Stationery Office N6187351 C3 07/09 Contents Chapter Page VOLUME -

Automobile Industry in India 30 Automobile Industry in India

Automobile industry in India 30 Automobile industry in India The Indian Automobile industry is the seventh largest in the world with an annual production of over 2.6 million units in 2009.[1] In 2009, India emerged as Asia's fourth largest exporter of automobiles, behind Japan, South Korea and Thailand.[2] By 2050, the country is expected to top the world in car volumes with approximately 611 million vehicles on the nation's roads.[3] History Following economic liberalization in India in 1991, the Indian A concept vehicle by Tata Motors. automotive industry has demonstrated sustained growth as a result of increased competitiveness and relaxed restrictions. Several Indian automobile manufacturers such as Tata Motors, Maruti Suzuki and Mahindra and Mahindra, expanded their domestic and international operations. India's robust economic growth led to the further expansion of its domestic automobile market which attracted significant India-specific investment by multinational automobile manufacturers.[4] In February 2009, monthly sales of passenger cars in India exceeded 100,000 units.[5] Embryonic automotive industry emerged in India in the 1940s. Following the independence, in 1947, the Government of India and the private sector launched efforts to create an automotive component manufacturing industry to supply to the automobile industry. However, the growth was relatively slow in the 1950s and 1960s due to nationalisation and the license raj which hampered the Indian private sector. After 1970, the automotive industry started to grow, but the growth was mainly driven by tractors, commercial vehicles and scooters. Cars were still a major luxury. Japanese manufacturers entered the Indian market ultimately leading to the establishment of Maruti Udyog. -

CHINA CORP. 2015 AUTO INDUSTRY on the Wan Li Road

CHINA CORP. 2015 AUTO INDUSTRY On the Wan Li Road Cars – Commercial Vehicles – Electric Vehicles Market Evolution - Regional Overview - Main Chinese Firms DCA Chine-Analyse China’s half-way auto industry CHINA CORP. 2015 Wan Li (ten thousand Li) is the Chinese traditional phrase for is a publication by DCA Chine-Analyse evoking a long way. When considering China’s automotive Tél. : (33) 663 527 781 sector in 2015, one may think that the main part of its Wan Li Email : [email protected] road has been covered. Web : www.chine-analyse.com From a marginal and closed market in 2000, the country has Editor : Jean-François Dufour become the World’s first auto market since 2009, absorbing Contributors : Jeffrey De Lairg, over one quarter of today’s global vehicles output. It is not Du Shangfu only much bigger, but also much more complex and No part of this publication may be sophisticated, with its high-end segment rising fast. reproduced without prior written permission Nevertheless, a closer look reveals China’s auto industry to be of the publisher. © DCA Chine-Analyse only half-way of its long road. Its success today, is mainly that of foreign brands behind joint- ventures. And at the same time, it remains much too fragmented between too many builders. China’s ultimate goal, of having an independant auto industry able to compete on the global market, still has to be reached, through own brands development and restructuring. China’s auto industry is only half-way also because a main technological evolution that may play a decisive role in its future still has to take off. -

SAIC Motor Is the Largest Automobile Group in China. Its Businesses

Page 1 of 2 TAN CHONG MOTOR HOLDINGS BERHAD (12969-P) - Memorandum of Understanding between TC Services Vietnam Co., Ltd, a Wholly-owned Subsidiary of Tan Chong Motor Holdings Berhad and SAIC Motor International Co., Ltd Introduction The Board of Directors of Tan Chong Motor Holdings Berhad (“TCMH” or “the Company”) wishes to announce that TC Services Vietnam Co., Ltd (“TC Services Vietnam ”) , a wholly-owned subsidiary of TCMH, had on 26 July 2019 entered into a Memorandum of Understanding (“MOU”) with SAIC Motor International Co., Ltd, (“SMIL”) to cooperate with each other in Vietnam market on CKD assembly, sales and distribution, as well as on imported CBU sales (“Project”) of certain automobile brand of products to be agreed between the parties (“Authorised Products”) with the objective of signing relevant cooperation agreements (“Cooperation Agreement”) to formalise the cooperation relationship. Information on TC Services Vietnam TC Services Vietnam is a wholly-owned subsidiary of TCMH incorporated in Vietnam. TC Services Vietnam is authorised to engage in retail distribution of various kinds of automobiles, provision of automotive maintenance and repair and spare parts services in accordance with the Laws of Vietnam. Information on SMIL SMIL is a wholly-owned subsidiary of SAIC Motor Corporation Limited (“SAIC Motor”) incorporated under the laws of the People’s Republic of China and having its registered office at 429H Room, No. 188, Ye Sheng Rd, China (Shanghai) Pilot Free Trade Zone, Shanghai, P.R.C. SMIL is engaged in the automotive business, including but not limited to the sale of automobiles and relevant components. SAIC Motor is the largest automobile group in China.