Singing-Waters Appalachia-SF2017.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feed Grain Transportation and Storage Assistance Regulations

CANADA CONSOLIDATION CODIFICATION Feed Grain Transportation and Règlement sur l’aide au Storage Assistance Regulations transport et à l’emmagasinage des céréales C.R.C., c. 1027 C.R.C., ch. 1027 Current to November 21, 2016 À jour au 21 novembre 2016 Published by the Minister of Justice at the following address: Publié par le ministre de la Justice à l’adresse suivante : http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca http://lois-laws.justice.gc.ca OFFICIAL STATUS CARACTÈRE OFFICIEL OF CONSOLIDATIONS DES CODIFICATIONS Subsections 31(1) and (3) of the Legislation Revision and Les paragraphes 31(1) et (3) de la Loi sur la révision et la Consolidation Act, in force on June 1, 2009, provide as codification des textes législatifs, en vigueur le 1er juin follows: 2009, prévoient ce qui suit : Published consolidation is evidence Codifications comme élément de preuve 31 (1) Every copy of a consolidated statute or consolidated 31 (1) Tout exemplaire d'une loi codifiée ou d'un règlement regulation published by the Minister under this Act in either codifié, publié par le ministre en vertu de la présente loi sur print or electronic form is evidence of that statute or regula- support papier ou sur support électronique, fait foi de cette tion and of its contents and every copy purporting to be pub- loi ou de ce règlement et de son contenu. Tout exemplaire lished by the Minister is deemed to be so published, unless donné comme publié par le ministre est réputé avoir été ainsi the contrary is shown. publié, sauf preuve contraire. -

Maine Revised Statutes 38 §467

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Maine Revised Statutes 38 §467 Maine Revised Statutes Title 38: WATERS AND NAVIGATION Chapter 3: PROTECTION AND IMPROVEMENT OF WATERS Subchapter 1: ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION BOARD Article 4-A: WATER CLASSIFICATION PROGRAM §467. Classification of major river basins All surface waters lying within the boundaries of the State that are in river basins having a drainage area greater than 100 square miles that are not classified as lakes or ponds are classified in this section. [1989, c. 764, §2 (AMD).] 1. Androscoggin River Basin. A. Androscoggin River, main stem, including all impoundments. (1) From the Maine-New Hampshire boundary to its confluence with the Ellis River - Class B. (2) From its confluence with the Ellis River to a line formed by the extension of the Bath-Brunswick boundary across Merrymeeting Bay in a northwesterly direction - Class C. [1989, c. 890, Pt. A, §40 (AFF); 1989, c. 890, Pt. B, §68 (AMD); MRSA T. 38, §467, sub-§1, ¶ A (AMD).] B. Little Androscoggin River Drainage. (1) Little Androscoggin River, main stem. (a) From the outlet of Bryant Pond to the Maine Central Railroad bridge in South Paris - Class A. (b) From the Maine Central Railroad bridge in South Paris to its confluence with the Androscoggin River - Class C. -

Storied Lands & Waters of the Allagash Wilderness

Appendixes 272 | A p p e n d i x A APPENDIX A: WATERWAY ANNIVERSARY RESOLUTION All copyrights and other rights to statutory text are reserved by the State of Maine. The text included in this publication has not been officially certified by the Secretary of State. JOINT RESOLUTION RECOGNIZING THE 50TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE ALLAGASH WILDERNESS WATERWAY HP1174, 127th Maine State Legislature WHEREAS, the Allagash Wilderness Waterway was established by the Maine Legislature on May 11, 1966; and WHEREAS, the people of Maine overwhelmingly passed a $1,500,000 bond issue on November 8, 1966 to develop the maximum wilderness character of the Allagash Wilderness Waterway; and WHEREAS, the Allagash Wilderness Waterway is a 92-mile water route from the Allagash River’s headwaters of Allagash Stream, Allagash Lake and Telos Lake, passing through major lakes and ponds and down the Allagash River, to West Twin Brook near Allagash Village; and WHEREAS, Maine residents and visitors to Maine enjoy paddling, camping and fishing in the Allagash Wilderness Waterway; and WHEREAS, many children from Maine and across the country have completed their first long-distance canoe trip paddling the Allagash Wilderness Waterway and thereby developed a lifelong love of the out-of-doors, the Maine woods and the State of Maine; and WHEREAS, paddling the Allagash Wilderness Waterway has resulted in positive life- changing experiences for many adult and young paddlers; and WHEREAS, the Allagash Wilderness Waterway is rich in Native American history; and WHEREAS, Henry David -

2007 ANNUAL REPORT for Public Reserved, Non-Reserved, and Submerged Lands to The

2007 ANNUAL REPORT for Public Reserved, Non-reserved, and Submerged Lands to the JOINT STANDING COMMITTEE on AGRICULTURE, CONSERVATION, AND FORESTRY Denny Pond Campsite, Deboullie Unit March 1 st , 2008 MAINE DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION Bureau of Parks and Lands Table of Contents I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.......................................................................................................... 3 II. 2007 HIGHLIGHTS .................................................................................................................... 3 III. PREFACE.................................................................................................................................... 4 IV. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................ 4 V. LAND MANAGEMENT PLANNING........................................................................................ 5 VI. NATURAL/HISTORIC RESOURCES ........................................................................................ 6 VII. WILDLIFE RESOURCES............................................................................................................ 8 VIII. RECREATION RESOURCES................................................................................................... 10 IX. TIMBER RESOURCES............................................................................................................. 13 X. TRANSPORTATION................................................................................................................ -

Maine Public Reserved, Nonreserved, and Submerged Lands

FY 2015 ANNUAL REPORT to the JOINT STANDING COMMITTEE on AGRICULTURE, CONSERVATION AND FORESTRY MAINE PUBLIC RESERVED, NONRESERVED, AND SUBMERGED LANDS Autumn View of North Crocker Peak at the Crocker Mountain Unit MAINE DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, CONSERVATION AND FORESTRY Bureau of Parks and Lands March 1, 2016 FY 2015 ANNUAL REPORT Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry Bureau of Parks and Lands TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………….. 1 II. HIGHLIGHTS – FY 2015 & FY 2016 (to date)………………………………….. 1 III. SCOPE OF RESPONSIBILITIES………………………………………………….. 5 IV. LAND MANAGEMENT PLANNING……………………………………………….. 6 V. NATURAL/HISTORIC RESOURCES……………………………………………... 7 VI. WILDLIFE RESOURCES…………………………………………………………… 10 VII. RECREATION RESOURCES……………………………………………………… 11 VIII. TIMBER RESOURCES……………………………………………………………... 17 IX. TRANSPORTATION………………………………………………………………… 22 X. PUBLIC ACCESS…………………………………………………………………… 22 XI. LAND TRANSACTIONS……………………………………………………………. 23 XII. SUBMERGED LANDS……………………………………………………………… 24 XIII. SHORE AND HARBOR MANAGEMENT FUND………………………………… 25 XIV. COASTAL ISLAND PROGRAM…………………………………………………… 25 XV. ADMINISTRATION………………………………………………………………….. 25 XVI. INCOME AND EXPENDITURES ACCOUNTING – FY 2015………………….. 28 XVII. FINANCIAL REPORT FOR FY 2016……………………………………………… 36 XVIII. CONCLUSION……………………………………………………………………….. 44 Appendix A: Map of BPL Property Interests in FY 2015………………………….…. 45 Appendix B: Map of Public Reserved Lands Management Regions……………….. 47 Appendix C: BPL Public Lands Harvest Data: FY 2006 - -

B682: a Recreational Study of the Upper St. John River Watershed Jeffrey L

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Bulletins Maine Agricultural and Forest Experiment Station 2-1970 B682: A Recreational Study of the Upper St. John River Watershed Jeffrey L. Hengsbach Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/aes_bulletin Part of the Forest Management Commons, and the Recreation, Parks and Tourism Administration Commons Recommended Citation Hengsbach, J.L. 1970. A recreational study of the upper St. John River watershed. Maine Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 682. This Report is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bulletins by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A RECREATIONAL STUDY OF THE UPPER ST. JOHN RIVER WATERSHED Jeffrey L. Hengsbach -:t ~~ CJT" ~ ....~ ,.u ~'t- .,. T -:> 0- DI:DJ'AAlr..... STATION FEBRUARY 1970 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writer wishes to express his appreciation to the following: Dr. Harold E. Young for his assistance and advice in all aspects of the research study. Director Albert D. Nutting, Dr. Johannes Delphendahl, Dr. Sanford D. Schemnitz, and Professor Frank K. Beyer, for their interest, assist ance and for critically reviewing the thesis. Seven Islands Land Co., Irving Pulp & Paper Co., International Paper Co., Great Northern Paper Co., Prentiss & Carlisle Co. Inc., Dunn Heirs, Lincoln Associates, et aI., for making the study possible through financial assistance. Landowner personnel, especially Allan Leighton and Albert Baker, for their assistance in the field and for securing and providing needed data and information. Fellow graduate students Allan Brackley and Peter Cummings for their assistance in the field work. -

2011 Annual Report Maine Public Reserved

2011 ANNUAL REPORT to the JOINT STANDING COMMITTEE on AGRICULTURE, CONSERVATION AND FORESTRY MAINE PUBLIC RESERVED, NONRESERVED, AND SUBMERGED LANDS Sandy Stream in Millinocket Forest March 1, 2012 MAINE DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION Bureau of Parks and Lands 2011 ANNUAL REPORT Maine Department of Conservation Bureau of Parks and Lands TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………….. 2 II. 2011 HIGHLIGHTS…………………………………………………………………..2 III. SCOPE OF RESPONSIBILITIES………………………………………………….. 5 IV. LAND MANAGEMENT PLANNING……………………………………………….. 8 V. NATURAL/HISTORIC RESOURCES……………………………………………...9 VI. WILDLIFE RESOURCES……………………………………………………………12 VII. RECREATION RESOURCES………………………………………………………14 VIII. TIMBER RESOURCES……………………………………………………………...19 IX. TRANSPORTATION………………………………………………………………… 23 X. PUBLIC ACCESS…………………………………………………………………… 24 XI. LAND TRANSACTIONS……………………………………………………………. 25 XII. SUBMERGED LANDS……………………………………………………………… 26 XIII. SHORE AND HARBOR MANAGEMENT FUND………………………………… 26 XIV. COASTAL ISLAND PROGRAM…………………………………………………… 26 XV. ADMINISTRATION………………………………………………………………….. 27 XVI. INCOME AND EXPENDITURES ACCOUNTING – CY 2011………………….. 28 XVII. FINANCIAL REPORT FOR FY 2013……………………………………………… 31 XVIII. CONCLUSION……………………………………………………………………….. 39 Appendix A: Map showing BPL Properties & Acquisitions in 2011…………………. 40 Appendix B: Summary of 2011 BPL Acquisitions and Dispositions………………… 41 Appendix C: Federal Forest Legacy Projects Approved and Pending……………... 43 Cover Photo by Andy Cutco, Maine Natural Areas Program I. INTRODUCTION principle -

By HFNICHOLSON Great Lakes Biolimnol

BIBLIOGRAPHY -ON THE LIMNOLOGY AND FISHERIES. OF CANADIAN FRESHWATERS. NO .''5 (REVISED). by H.F.NICHOLSON Great Lakes Biolimnology Laboratory, Canada Centre for Inland Waters, 867 Lakeshore Road, Burlington, Ontario. L7R 4A6 PREFACE This is a revised edition of Bibliography No.5, published in 1978 as Fish. Environm.Can., Fish.Mar.Serv., Techn.Rept., (804). Due to budget restrictions and the high cost of printing, combined with an expanding distribution list, it is no longer possible to publish this series as Technical Reports. Instead, each number will be issued in this present looseleaf form as an unpublished report of the Great Lakes Biolimnology Laboratory. Please note that those from outside Canada requesting copies of this series will be sent the Reference Indexes only. However, the Canadian Freshwater Features Section will be sent if specifically requested. This issue can be referenced as:- Nicholson, H.F. 1982. "Bibliography on the limnology and fisheries of Canadian freshwaters. No.5(revised)". Can.Dept.Fish.Oceans, Pacific & Freshw.Fish., Great Lakes Biolimnol.Lab., Unpubl.Rept. FORMAT The bibliography is divided into two sections:- (1). Reference Index Each of these references contains information on the limnology and fisheries of Canadian freshwaters. They are numbered and appear in numerical order. This enumeration is consecutive and continuous through the bibliography series. (2). Freshwater Feature Index This section is divided into alphabetical order of provinces and within each province the freshwater feature names are in alphabetical order. The coordinates (in minutes and degrees, latitude and longitude) are given for each feature except for British Columbia where, for the most part, the quadrilateral indexing system is used. -

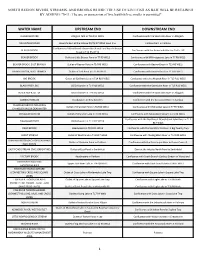

Water Name Upstream End Downstream End

NORTH REGION RIVERS, STREAMS, AND BROOKS WHERE THE USE OF LIVE FISH AS BAIT WILL BE RETAINED BY ADDING: "S-11: The use or possession of live baitfish/live smelts is permitted" WATER NAME UPSTREAM END DOWNSTREAM END ALLAGASH RIVER Allagash Falls in T15 R11 WELS Confluence with the Saint John River in Allagash AROOSTOOK RIVER Blue Markers at the Oxbow Plt/T9 R7 WELS town line Caribou Dam in Caribou Confluence of West Branch Beaver Brook and East Branch Beaver BEAVER BROOK Confluence with the Aroostook River in Castle Hill Brook in T13 R5 WELS BEAVER BROOK Outlet of Little Beaver Pond in T7 R9 WELS Confluence with Millimagassett Lake in T7 R8 WELS BEAVER BROOK, EAST BRANCH Outlet of Beaver Pond in T14 R5 WELS Confluence with Beaver Brook in T13 R5 WELS BEAVER BROOK, WEST BRANCH Outlet of Lost Pond in T15 R6 WELS Confluence with Beaver Brook in T13 R5 WELS BIG BROOK Outlet of Big Brook Lake in T14 R10 WELS Confluence with the Allagash River in T15 R11 WELS BLACK RIVER, BIG US/CA border in T14 R16 WELS Confluence with the Saint John River in T15 R13 WELS BLACK RIVER, LITTLE US/CA border in T19 R12 WELS Confluence with the Saint John River in Allagash CARIBOU STREAM Headwaters in New Sweden Confluence with the Aroostook River in Caribou CHANDLER BROOK INCLUDING Outlet of Chandler Pond in T8 R10 WELS Confluence with Millinocket Lake in T7 R9 WELS CHANDLER BROOK DEADWATER CHANDLER STREAM Outlet of Chandler Lake in T9 R8 WELS Confluence with Mooseleuk Stream in T9 R8 WELS Confluence with the Northwest Branch Saint John River in T11 DAAQUAM RIVER -

Annual Report 1958-59-, Which Also Contains Lists of Its Scientific Staff and Various Publications

e, ‘-;/- N 1,101te _Ale)OCEe3 Vet VISI-e'PeS 11,0011. esràzs s.rr., 240 Oefe.10i CeA.D.A. • • .. 'UPI. 0E6 , s.. , Being the Ninety-second Annual Fisheries Report of the Government of Canada ERRATA Department of Fisheries of Canada, Annual Report, 1958-59. Page 32, paragraph 1, line 4, the figure '1960' should read '1959 1 . Page 51, paragraph 1, line 8, the figure '1947' should read '1957'. 78047-8--1 4 THE QuEEN's PRINTER AND CONTROLLER OF STATIONERY OTTAWA, 1960 Price 50 cents. Cat. No. Fs. 1-59 To His Excellency Major-General Georges P. Vanier, D.S.O., M.C., C.D., Governor General and Commander-in-Chief of Canada. May it Please Your Excellency : I have the honour herewith, for the information of Your Excellency and the Parliament of Canada, to present the Annual Report of the Department of Fisheries for the fiscal year 1958-1959. Respectfully submitted Minister of Fisheries. 78047-8--1I 4 To The Honourable J. Angus MaCLean, M.P., Minister of Fisheries, Ottawa, Canada. Sir: I submit herewith the Annual Report of the Department of Fisheries for the fiscal year 1958-1959. I have the honour to be, Sir, Your obedient servant e,6) • Deputy Minister. CONTENTS Page Introduction 7 Conservation and Development Service 10 Departmental Vessels 29 Inspection and Consumer Service 32 Economics Service 44 Information and Educational Service 46 Industrial Development Service 49 1 Fishermen's Indemnity Plan 51 Fisheries Prices Support Board 53 Fisheries Research Board of Canada 56 International Commissions 70 Special Committees 92 The Fishing Industry 93 Statistics of the Fisheries 99 APPENDICES 1. -

Fishing Regulations

STATE OF MAINE OPEN WATER FISHING REGULATIONS Regulations Effective January 2008 - March 31, 2010 www.maine.gov/ifw SPECIAL REGULATIONS FOR OPEN WATER FISHING Waters which have exceptions to the general law are listed by county. In most cases, the exception will be one of the codes listed below and may affect only a portion of the regulations that govern that particular body of water, i.e. only the bag limit on salmon is different from the general law in which case it would read as follows: Smith Pond, Anytown. S-22. All other provisions of general law would apply. S-1: Closed to the taking of smelts. S-17: Daily bag limit on trout: 2 fi sh; minimum S-2: Closed to the taking of smelts, except by length limit: 10 inches, only 1 may hook and line. exceed 12 inches. S-3: Tributaries closed to the taking of smelts. S-18: Daily bag limit on trout: 1 fi sh, minimum length limit 18 inches. S-4: Use or possession of live fi sh as bait is prohibited. (The use of dead fi sh, salmon S-19: Daily bag limit on trout: 2 fi sh. eggs, or worms is permitted). S-20: Daily bag limit on white perch: 25 fi sh. S-5: Fly fi shing only. S-21: Daily bag limit on trout: 1 fi sh, minimum S-6: Artifi cial lures only. length limit 14 inches. S-7: Boundary waters with New Brunswick, S-22: Daily bag limit on landlocked salmon: 1 see page 56. fi sh. -

DFO Lil~Il ~ ~1L[1I11[1I1i1l111~1Lll1i[1Li $ Qu E 02011319

DFO lil~il ~ ~1l[1i11[1i1i1l111~1lll1i[1li $ qu e 02011319 CANADA FISH CULTURE DEVELOPMENT A Report of the Fish Culture Development Branch of the Conservation and Development Service SH 37 A11 Reprinted from the 'Twenty"Fifth Annual Report 1954 of the Department of Fisheries of Canada c. 2 RARE SH 37A11 1954 c.2 RARE Canada. Fish Culture Development Branch Fish culture development. a report of the J 02011319 c.2 SH 37 A11 1954 c.2 RARE d Fish Culture Development Branch Cana a. rt of the Fish culture development. a repo 02011319 c.2 I• FISH CULTURE DEVELO NDER the British North America Act, legislative jurisdiction in coastal U and inland fisheries was given to the Government of Canada. Since that time, however, as a result of various agreements, certain provinces have accepted in a greater or lesser degree the administration of the fisheries within their bound aries. Thus the Province of Quebec administers all its fisheries both freshwater and marine. The Provinces of Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta 1 assume responsibility for the freshwater species while the Government of Canada handles such marine problems as occur. In British Columbia and Newfoundland the Government of Canada is completely responsible for the marine and anadromous (salmon, smelts, etc.) fish while the provinces take charge of the purely freshwater species. In Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, the Northwest Territories and the Yukon Territory, the Government of Canada carries out its full responsibility in exerting not only legislative but administrative control. It should be stressed that everywhere in Canada, fisheries legislation is federal even though certain provinces may assume enforcement responsibility.