THE LAST HURRAH by EDWIN O'connor— Adapted for SCREEN STORIES by JEAN FRANCIS WEBB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cial Climber. Hunter, As the Professor Responsible for Wagner's Eventual Downfall, Was Believably Bland but Wasted. How Much

cial climber. Hunter, as the professor what proves to be a sordid suburbia, responsible for Wagner's eventual are Mitchell/Woodward, Hingle/Rush, downfall, was believably bland but and Randall/North. Hunter's wife is wasted. How much better this film attacked by Mitchell; Hunter himself might have been had Hunter and Wag- is cruelly beaten when he tries to ner exchanged roles! avenge her; villain Mitchell goes to 20. GUN FOR A COWARD. (Universal- his death under an auto; his wife Jo- International, 1957.) Directed by Ab- anne Woodward goes off in a taxi; and ner Biberman. Cast: Fred MacMurray, the remaining couples demonstrate Jeffrey Hunter, Janice Rule, Chill their new maturity by going to church. Wills, Dean Stockwell, Josephine Hut- A distasteful mess. chinson, Betty Lynn. In this Western, Hunter appeared When Hunter reported to Universal- as the overprotected second of three International for Appointment with a sons. "Coward" Hunter eventually Shadow (released in 1958), he worked proved to be anything but in a rousing but one day, as an alcoholic ex- climax. Not a great film, but a good reporter on the trail of a supposedly one. slain gangster. Having become ill 21. THE TRUE STORY OF JESSE with hepatitis, he was replaced by JAMES. (20th Century-Fox, 1957.) Di- George Nader. Subsequently, Hunter rected by Nicholas Ray. Cast: Robert told reporters that only the faithful Wagner, Jeffrey Hunter, Hope Lange, Agnes Moorehead, Alan Hale, Alan nursing by his wife, Dusty Bartlett, Baxter, John Carradine. whom he had married in July, 1957, This was not even good. -

E Thomas Jefferson, a Film by Ken Burns

Kick offl TRMA NIGHT, hosted by NHPR's Civics 101 Podcast A Come and see how much you know about our Founding Documents! J e Tuesday, January 28, 6pm, Ffrost Sawyer Tavern at the Three Chimneys Inn n u The History of the New Hampshire Primary e A NH Humanities Program presented by John Gfroerer r Wednesday, January 29, 7pm, Madbury Public Library An Introduction to the Declaration of lndependence A talk by Eliga Gould, UNH Professor of History Monday, February 3, 6pm, Durham Public Library join a conversation about the Declaration of lndependence with a UNH graduate student of American History - bring your thoughts & questions Thursday, February 6, 6pm, Durham Public Library 1776, (1972) an historical musical comedy about the Declaration of lndependence nominated for the Golden Globe Award for Best Picture Sunday, February 9, 4pm, Freedom Cafe, Durham E Thomas Jefferson, a film by Ken Burns Part 1: Thursday, February 13, 6 pm, Community Church of Durham ' Part 2: Tuesday, February 18, 6 pm, Community Church of Durham A community reading of "What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?" by Frederick Douglass Sunday, February 16, 4pm, Waysmeet Center, Durham A day trip to the NH Historical Society and a tour of the NH State Capitol To signup go to durhamrec.recdesk.com Wednesday, February 19, organized by Durham Parks and Recreation An introduction to the US Constitution and Bill of Rights A talk by Eliga Gould, UNH Professor of History Monday, March 2, 6pm, Madbury Public Library Join a conversation about the US Constitution with a UNH graduate student of American History - bring your thoughts & questions Thursday, March 5, 6pm, Madbury Public Library Notfor Ourselves Alone: The Story of Elizabeth Cmy Stanton & Susan B. -

Good-Bye to All That: the Rise and Demise of Irish America Shaun O'connell University of Massachusetts Boston, [email protected]

New England Journal of Public Policy Volume 9 | Issue 1 Article 9 6-21-1993 Good-bye to All That: The Rise and Demise of Irish America Shaun O'Connell University of Massachusetts Boston, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp Part of the Nonfiction Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation O'Connell, Shaun (1993) "Good-bye to All That: The Rise and Demise of Irish America," New England Journal of Public Policy: Vol. 9: Iss. 1, Article 9. Available at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp/vol9/iss1/9 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in New England Journal of Public Policy by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Good-bye to The Rise and All That Demise of Irish America Shaun O'Connell The works discussed in this article include: The Rascal King: The Life and Times of James Michael Curley 1874-1958, by Jack Beatty. 571 pages. Addison -Wesley, 1992. $25.00. JFK: Reckless Youth, by Nigel Hamilton. 898 pages. Random House, 1992. $30.00. Textures of Irish America, by Lawrence J. McCaffrey. 236 pages. Syracuse University Press, 1992. $29.95. Militant and Triumphant: William Henry O'Connell and the Catholic Church in Boston, by James M. O'Toole. 324 pages. University of Notre Dame Press, 1992. $30.00. When I was growing up in a Boston suburb, three larger-than-life public figures defined what it meant to be an Irish-American. -

Ebook Download the Last Hurrah a Novel 1St Edition Kindle

THE LAST HURRAH A NOVEL 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Edwin OConnor | 9780226321417 | | | | | The Last Hurrah A Novel 1st edition PDF Book At the beginning of the book, Skeffington is 72 and has been giving signs that he might consider retiring from public life at the end of his current term. On one memorable occasion he had gone so far as to speak with a certain dreaminess of the joys of retirement, of the quiet time of withdrawal which would follow a lifetime spent in the service of the public. Hidden categories: All articles with unsourced statements Articles with unsourced statements from December Why, the mind positively boggles at the presumption of these men! What would you do? MA: Thank ye, Festus. This announcement had been carefully timed so that it would appear in the city edition of all morning papers; in this way — Skeffington had explained to his nephew that noon — the maximum desirable effect would be achieved; the majority of his opponents would learn the bad news over their morning coffee. Publisher: Little, Brown and Company, Boston. And Skeffington knew that in the coming campaign he could depend upon few things as surely as he could upon the unrelenting, frenzied opposition of his ancient foe, coming at him from street corners, from the radio, from television. You heard with your own ears what he had to say. First edition. This was a matter about which there had been public speculation for a good while: for, in fact, four years, ever since he had been inaugurated for what his opponents had fondly hoped was the last time. -

Michael C. Connolly, “The First Hurrah: James Michael Curley Versus the 'Goo-Goos' in the Boston Mayoralty Election 1914

Michael C. Connolly, “The First Hurrah: James Michael Curley versus the ‘Goo-Goos’ in the Boston Mayoralty Election 1914” Historical Journal of Massachusetts Volume 30, No. 1 (Winter 2002). Published by: Institute for Massachusetts Studies and Westfield State University You may use content in this archive for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the Historical Journal of Massachusetts regarding any further use of this work: [email protected] Funding for digitization of issues was provided through a generous grant from MassHumanities. Some digitized versions of the articles have been reformatted from their original, published appearance. When citing, please give the original print source (volume/ number/ date) but add "retrieved from HJM's online archive at http://www.westfield.ma.edu/mhj/.” Editor, Historical Journal of Massachusetts c/o Westfield State University 577 Western Ave. Westfield MA 01086 The First Hurrah: James Michael Curley versus the “Goo-Goos” in the Boston Mayoralty Election of 1914 By Michael C. Connolly On January 13, 1914 James Michael Curley defeated South Boston’s Thomas J. Kenny in the race to serve as Mayor of Boston for the next four years. In Curley’s lengthy political career, spanning fifty years in and out of elective office, he would run for Mayor ten times and be successful in four of those contests. There is much about the election of 1914 which suggests it to be perhaps the most crucial and formative of Curley’s political life. He was not the first Irishman elected as Boston’s Mayor, that distinction rested with Irish-born Hugh O’Brien who was elected in 1885. -

The Irish-American Experience in the Fiction of Edwin O'connor

THE IRISH-AMERICAN EXPERIENCE IN THE FICTION OF EDWIN O'CONNOR By ROBERT DAVID BANKS f' Bachelor of Arts Boston College Chestnut Hill,· Massachusetts 1972 Master of Arts Boston College Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts 1975 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY July, 1983 -lh.Q..:,{';;> \1~bl) 0~1~ 1., t'Ofl.';L THE IRISH-AMERICAN EXPERIENCE IN THE FICTION OF EDWIN O'CONNOR Thesis Approved: Thesis Adviser /. J-- . Ag fl e~d ) Jr .._ ~ · fl~'de ~ollege ii PREFACE In his fiction, Edwin O'Connor chronicled the final stages in the acculturation of the American Irish and the resulting attenuation of ethnic Irish distinctiveness. He focused his fictional lens on those three areas of the Irish-American experience that had the most influence on and were most influenced by 11fe in America -- politics, religion, and the family. This study takes an interdisciplinary approach to O'Connor's novels about the American Irish. The following chapters will provide a brief historical analysis of Irish political, religious, and family life, followed by a thorough textual examination of O'Connor's handling of these themes in his fiction. Through this antiphonal style of presentation, I hope to show not only how accurately O'Connor apprehended historical facts about the American Irish, but also how skillfully he animated and enriched them through his craft as a novelist. I was first introduced to the fiction of Edwin O'Connor in 1966, the year in which his last novel was published. -

The John Ford Collection

The John Ford Collection The John Ford collection of manuscripts at the Lilly Library offers a view of Ford's entire motion picture career, from the silent era to his last movie in 1966. The material in this collection was acquired from Ford's children and grandson after his death . It was used extensively, but not exhaustively, by Ford's grandson Dan Ford in writing his biography Pappy: The Life of John Ford and includes much of the research material accumulated by Dan Ford for his book. The collection covers the years from 1906 to 1976 and contains approximately seven thousand items, of which twenty-five hundred are correspondence. John Ford was born Sean Aloysius Feeney in Portland, Maine, in 1895. He changed his name after joining his older brother Fran cis, who had taken the name of Ford, in Hollywood in 1913. He began his career as a prop man, stunt man, and actor, moving to directing in 1917 with a two-reeler entitled The Tornado. He spent the rest of his life directing films, through the transition from silents to sound, making over 130 in all and winning six Academy Awards. From 1917 until 1930 Ford directed at least 66 films, a great many of which were westerns starring the cowboy actor Harry Carey. Early in his career Ford was most often associated with Universal Studio but by the early twenties he was under contract to the Fox Film Corporation (later the Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corporation) until after World War II. It was at Fox that he had his first major success, with The Iron Horse in 1924. -

Explaining Boston's Irish and Their Politics

Thomas H. O'Connor. The Boston Irish: A Political History. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1995. xix + 363 pp. $30.00, library, ISBN 978-1-55553-220-8. Reviewed by John M. Allswang Published on H-Pol (June, 1998) Thomas O'Connor's study seeks to describe O'Connor starts with colonial Irish immigra‐ and explain the development of Boston Irish tion, noting that, even though the immigrants Catholic politics from its origins to the present were overwhelmingly Protestant, they encoun‐ day. His central thesis is that the Boston experi‐ tered strong animosity from the Yankee leader‐ ence was unique, quite different from what hap‐ ship of New England. Over time, the Irish Protes‐ pened in Irish-American politics in other cities, tants did assimilate into colonial society, but the and that this was due, essentially, to the interplay small minority of Irish Roman Catholics never of Yankee Protestant and Irish Catholic culture had that option. Anti-Catholic measures were and ambitions. While not entirely persuasive, common in the colonies, although this was some‐ O'Connor does make a good argument for his the‐ what meliorated by common cause in the revolu‐ sis, and in the process provides a valuable addi‐ tionary and constitutional periods. The very small tion to our understanding of Irish politics in number of Irish Catholics made the problem less American cities generally. grave than might otherwise have been the case The book differs from earlier studies (such as (here, as elsewhere, the book suffers from vague‐ William Shannon's The American Irish and Ed‐ ness: rarely are actual numbers given). -

The Rescue of Evangelina Cisneros: "While Others Talk the Journal Acts"

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1984 The rescue of Evangelina Cisneros: "While others talk the Journal acts" Kyle Hunter Albert The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Albert, Kyle Hunter, "The rescue of Evangelina Cisneros: "While others talk the Journal acts"" (1984). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 9199. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/9199 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 Th i s is a n unpublished m a n u s c r i p t in w h i c h c o p y r i g h t s u b s i s t s . An y f u r t h e r r e p r i n t i n g o f its c o n t e n t s m u s t b e a p p r o v e d BY t h e a u t h o r . MANSFIELD L i b r a r y Un i v e r s i t y o f Ji i o m t a/ja D a t e : _____ 1 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

No Seat at the Table Boston’S Power Massinc Thanks the Many Individuals and Organizations Whose Support Makes Commonwealth Possible

WILLIAM LANTIGUA: THE JAMES MICHAEL CURLEY OF LAWRENCE PRESORTED STANDARD U.S. POSTAGE PAID ABERDEEN, SD 11 Beacon Street, Suite 500 PERMIT NO. 200 Boston, MA 02108 Address Service Requested BOARDROOM DIVERSITY / LAWRENCE MAYOR / BRAYTON POINT / BRAYTON MAYOR / LAWRENCE DIVERSITY BOARDROOM POLITICS, IDEAS & CIVIC LIFE IN MASSACHUSETTS Visit MassINC online at www.massinc.org No seat at the table Boston’s power MassINC thanks the many individuals and organizations whose support makes CommonWealth possible. structure still chairman’s circle sponsors Metropolitan Area Planning Massachusetts Technology CWC Builders excludes blacks, Anonymous (2) Council Collaborative Delta Dental Plan of ArtPlace America Mintz, Levin, Cohn, Ferris, The MENTOR Network Massachusetts Hispanics Glovsky and Popeo, P.C. The Boston Foundation New England Regional Emerson College NAIOP Massachusetts Council of Carpenters John S. and James L. Knight Massachusetts Association Foundation National Grid Theodore Edson Parker of REALTORS® Foundation MassMutual Financial Group Partners HealthCare Meketa Investment Group Trinity Financial Nellie Mae Education Merrimack Valley Economic Foundation major sponsors Tufts Health Plan Development Council Anonymous Public Welfare Foundation University of Massachusetts Northeastern University Citizens Bank State House News Service Nutter McClennen & Fish LLP lead sponsors Irene E. & George A. Davis Retailers Association of Foundation Anonymous contributing sponsors Massachusetts Foley Hoag LLP Barr Foundation The Architectural Team -

The Long Winding Road to the White House: Caucuses, Primaries and National Party Conventions in the History of American Presidential Elections

Barack Obama at the Democratic National Convention Charlotte, North Carolina, September 2012 The Long Winding Road to the White House: caucuses, primaries and national party conventions in the history of American presidential elections Michael Dunne Almost the Last Hurrah rest of the Republican party will seek to formerly British colonies expanded first At last we know officially. In late August increase their power in the US Congress in North America and then overseas to at their 40th national convention in by enlarging their majority in the House exert global power, the ‘more perfect Tampa, Florida, the Republican party of Representatives (where Ryan is a very union’ proposed by the Framers in 1787 formally nominated its candidates influential member) and dislodging the has changed little in its organic law. to run for election as president and Democrats from their narrow control of Certainly 27 formal amendments have vice-president of the United States the Senate. been made to the Philadelphian original; of America. Mitt Romney, former but ten of these (the Bill of Rights) were governor of Massachusetts and son of a The constitutional framework added almost immediately as conditions governor of Michigan (himself once a and the numbers game for ratifying the foundational text itself. presidential hopeful), has been chosen A great paradox characterizes the One aspect which has remained virtually to oppose President Barack Obama, discussion and practice of American unchanged is Article II, concerning the triumphing after an initially bruising politics. In a society which is self- ‘executive power’ and its ‘vest[ing] in a primary campaign – and needing to bind consciously forward-looking, where president….’; and under this rubric is up the Republican party’s wounds (to every speech from local to national level detailed the method of electing the chief echo Abraham Lincoln, the first and for invokes the future, the political system and executive. -

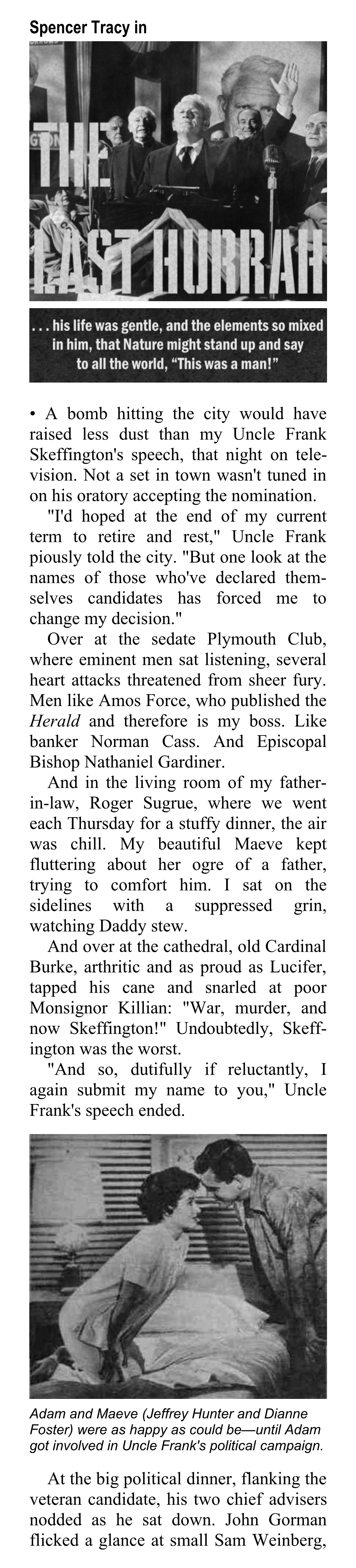

Spencer Tracy In

Adam and Maeve (Jeffrey Hunter and Dianne Foster) were as happy as could be—until Adam got involved in Uncle Frank's political campaign. • A bomb hitting the city would have raised less dust than my Uncle Frank Skeffington's speech, that night on television. Not a set in town wasn't tuned in on his oratory accepting the nomination. "I'd hoped at the end of my current term to retire and rest," Uncle Frank piously told the city. "But one look at the names of those who've declared themselves candidates has forced me to change my decision." Over at the sedate Plymouth Club, where eminent men sat listening, several heart attacks threatened from sheer fury. Men like Amos Force, who published the Herald and therefore is my boss. Like banker Norman Cass. And Episcopal Bishop Nathaniel Gardiner. And in the living room of my father-in-law, Roger Sugrue, where we went each Thursday for a stuffy dinner, the air was chill. My beautiful Maeve kept fluttering about her ogre of a father, trying to comfort him. I sat on the sidelines with a suppressed grin, watching Daddy stew. And over at the cathedral, old Cardinal Burke, arthritic and as proud as Lucifer, tapped his cane and snarled at poor Monsignor Killian: "War, murder, and now Skeffington!" Undoubtedly, Skeffington was the worst. "And so, dutifully if reluctantly, I again submit my name to you," Uncle Frank's speech ended. continued >> Spencer Tracy in Twice governor, four times mayor, he'd never known defeat... until now! At the big political dinner, flanking the veteran candidate, his two chief V below advisers nodded as he sat down.