From the Scale Model of the Sky to the Armillary Sphere

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unit 2 Basic Concepts of Positional Astronomy

Basic Concepts of UNIT 2 BASIC CONCEPTS OF POSITIONAL Positional Astronomy ASTRONOMY Structure 2.1 Introduction Objectives 2.2 Celestial Sphere Geometry of a Sphere Spherical Triangle 2.3 Astronomical Coordinate Systems Geographical Coordinates Horizon System Equatorial System Diurnal Motion of the Stars Conversion of Coordinates 2.4 Measurement of Time Sidereal Time Apparent Solar Time Mean Solar Time Equation of Time Calendar 2.5 Summary 2.6 Terminal Questions 2.7 Solutions and Answers 2.1 INTRODUCTION In Unit 1, you have studied about the physical parameters and measurements that are relevant in astronomy and astrophysics. You have learnt that astronomical scales are very different from the ones that we encounter in our day-to-day lives. In astronomy, we are also interested in the motion and structure of planets, stars, galaxies and other celestial objects. For this purpose, it is essential that the position of these objects is precisely defined. In this unit, we describe some coordinate systems (horizon , local equatorial and universal equatorial ) used to define the positions of these objects. We also discuss the effect of Earth’s daily and annual motion on the positions of these objects. Finally, we explain how time is measured in astronomy. In the next unit, you will learn about various techniques and instruments used to make astronomical measurements. Study Guide In this unit, you will encounter the coordinate systems used in astronomy for the first time. In order to understand them, it would do you good to draw each diagram yourself. Try to visualise the fundamental circles, reference points and coordinates as you make each drawing. -

Sphere Confusion: a Textual Reconstruction of Instruments and Observational Practice in First-Millennium CE China Daniel Patrick Morgan

Sphere confusion: a textual reconstruction of instruments and observational practice in first-millennium CE China Daniel Patrick Morgan To cite this version: Daniel Patrick Morgan. Sphere confusion: a textual reconstruction of instruments and observa- tional practice in first-millennium CE China . Centaurus, Wiley, 2016, 58 (1-2), pp.87-103. halshs- 01374805v3 HAL Id: halshs-01374805 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01374805v3 Submitted on 4 Oct 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - ShareAlike| 4.0 International License Centaurus, 58.1 (2016) Sphere Confusion: a Textual Reconstruction of Astronomical Instruments and Observational Practice in First-millennium CE China * Daniel Patrick MORGAN Abstract: This article examines the case of an observational and demonstration- al armillary sphere confused, one for the other, by fifth-century historians of astronomy He Chengtian and Shen Yue. Seventh-century historian Li Chunfeng dismisses them as ignorant, supplying the reader with additional evidence. Using their respective histories and what sources for the history of early imperial ar- millary instruments survive independent thereof, this article tries to explain the mix-up by exploring the ambiguities of ‘observation’ (guan) as it was mediated through terminology, text, materiality and mathematics. -

Exercise 3.0 the CELESTIAL HORIZON SYSTEM

Exercise 3.0 THE CELESTIAL HORIZON SYSTEM I. Introduction When we stand at most locations on the Earth, we have the distinct impression that the Earth is flat. This occurs because the curvature of the small area of the Earth usually visible is very slight. We call this “flat Earth” the Plane of the Horizon and divide it up into 4 quadrants, each containing 90o, by using the cardinal points of the compass. The latter are the North, South, East, and west points of the horizon. We describe things as being vertical or “straight up” if they line up with the direction of gravity at that location. It is easy for us to determine “straight up” because we have a built in mechanism for this in the inner ear (the semicircular canals). Because it seems so “natural”, we build a coordinate system on these ideas called the Horizon System. The Celestial Horizon System is one of the coordinate systems that astronomers find useful for locating objects in the sky. It is depicted in the Figure below. Figure 1. The above diagram is a skewed perspective, schematic diagram of the celestial sphere with circles drawn only for the half above the horizon. Circles on the far side, or western half, of the celestial sphere are drawn as dashed curves. All the reference circles of this system do not share in the rotation of the celestial sphere and, therefore, this coordinate system is fixed with respect to a given observer. The basis for the system is the direction of gravity. We can describe this as the line from the observer on the surface of the Earth through the center of the Earth. -

Abd Al-Rahman Al-Sufi and His Book of the Fixed Stars: a Journey of Re-Discovery

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following reference: Hafez, Ihsan (2010) Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi and his book of the fixed stars: a journey of re-discovery. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/28854/ The author has certified to JCU that they have made a reasonable effort to gain permission and acknowledge the owner of any third party copyright material included in this document. If you believe that this is not the case, please contact [email protected] and quote http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/28854/ 5.1 Extant Manuscripts of al-Ṣūfī’s Book Al-Ṣūfī’s ‘Book of the Fixed Stars’ dating from around A.D. 964, is one of the most important medieval Arabic treatises on astronomy. This major work contains an extensive star catalogue, which lists star co-ordinates and magnitude estimates, as well as detailed star charts. Other topics include descriptions of nebulae and Arabic folk astronomy. As I mentioned before, al-Ṣūfī’s work was first translated into Persian by al-Ṭūsī. It was also translated into Spanish in the 13th century during the reign of King Alfonso X. The introductory chapter of al-Ṣūfī’s work was first translated into French by J.J.A. Caussin de Parceval in 1831. However in 1874 it was entirely translated into French again by Hans Karl Frederik Schjellerup, whose work became the main reference used by most modern astronomical historians. In 1956 al-Ṣūfī’s Book of the fixed stars was printed in its original Arabic language in Hyderabad (India) by Dārat al-Ma‘aref al-‘Uthmānīa. -

The Geography of Ptolemy Elucidated

The Grography of Ptolemy The geography of Ptolemy elucidated Thomas Glazebrook Rylands 1893 • A brief outline of the rise and progress of geographical inquiry prior to the time of Ptolemy. §1.—Introductory. IN tracing the early progress of Geography it is necessary to remember that, like all other sciences, it arose from “ small beginnings.” When men began to move from place to place they naturally desired to tell the tale of their wanderings, both for their own satisfaction and for the information of others. Such accounts have now perished, but their results remain in the earliest records extant ; hence, it is impossible to begin an investigation into the history of Geography at the true fountain-head, though it is in some instances possible to guess the nature of the source from the character of the resultant stream. A further difficulty lies in the question as to where the science of Geography begins. A Greek would probably have answered when some discoverer first invented a method for map- ping out the distance between certain places, which distance conversely could be ascertained directly from the map. In accordance with modern method, the science of Geography might be said to begin when the subject ceased to be dealt with mythically or dogmatically ; when facts were collected and reduced to laws, while these laws again, or their prior facts, were connected with other laws—in the case of Geography with those of Mathematics and Astro- nomy. Perhaps it would be better to follow the latter principle of division, and consequently the history of Geography may be divided into two main stages—“ Pre-Scientific” and Scientific Geography—though strictly speaking, the name of Geography should be applied to the latter alone. -

Thinking Outside the Sphere Views of the Stars from Aristotle to Herschel Thinking Outside the Sphere

Thinking Outside the Sphere Views of the Stars from Aristotle to Herschel Thinking Outside the Sphere A Constellation of Rare Books from the History of Science Collection The exhibition was made possible by generous support from Mr. & Mrs. James B. Hebenstreit and Mrs. Lathrop M. Gates. CATALOG OF THE EXHIBITION Linda Hall Library Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering and Technology Cynthia J. Rogers, Curator 5109 Cherry Street Kansas City MO 64110 1 Thinking Outside the Sphere is held in copyright by the Linda Hall Library, 2010, and any reproduction of text or images requires permission. The Linda Hall Library is an independently funded library devoted to science, engineering and technology which is used extensively by The exhibition opened at the Linda Hall Library April 22 and closed companies, academic institutions and individuals throughout the world. September 18, 2010. The Library was established by the wills of Herbert and Linda Hall and opened in 1946. It is located on a 14 acre arboretum in Kansas City, Missouri, the site of the former home of Herbert and Linda Hall. Sources of images on preliminary pages: Page 1, cover left: Peter Apian. Cosmographia, 1550. We invite you to visit the Library or our website at www.lindahlll.org. Page 1, right: Camille Flammarion. L'atmosphère météorologie populaire, 1888. Page 3, Table of contents: Leonhard Euler. Theoria motuum planetarum et cometarum, 1744. 2 Table of Contents Introduction Section1 The Ancient Universe Section2 The Enduring Earth-Centered System Section3 The Sun Takes -

Our Place in the Universe Sun Kwok

Our Place in the Universe Sun Kwok Our Place in the Universe Understanding Fundamental Astronomy from Ancient Discoveries Second Edition Sun Kwok Faculty of Science The University of Hong Kong Hong Kong, China This book is a second edition of the book “Our Place in the Universe” previously published by the author as a Kindle book under amazon.com. ISBN 978-3-319-54171-6 ISBN 978-3-319-54172-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-54172-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017937904 © Springer International Publishing AG 2017 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

10 · Greek Cartography in the Early Roman World

10 · Greek Cartography in the Early Roman World PREPARED BY THE EDITORS FROM MATERIALS SUPPLIED BY GERMAINE AUJAe The Roman republic offers a good case for continuing to treat the Greek contribution to mapping as a separate CONTINUITY AND CHANGE IN THEORETICAL strand in the history ofclassical cartography. While there CARTOGRAPHY: POLYBIUS, CRATES, was a considerable blending-and interdependence-of AND HIPPARCHUS Greek and Roman concepts and skills, the fundamental distinction between the often theoretical nature of the Greek contribution and the increasingly practical uses The extent to which a new generation of scholars in the for maps devised by the Romans forms a familiar but second century B.C. was familiar with the texts, maps, satisfactory division for their respective cartographic in and globes of the Hellenistic period is a clear pointer to fluences. Certainly the political expansion of Rome, an uninterrupted continuity of cartographic knowledge. whose domination was rapidly extending over the Med Such knowledge, relating to both terrestrial and celestial iterranean, did not lead to an eclipse of Greek influence. mapping, had been transmitted through a succession of It is true that after the death of Ptolemy III Euergetes in well-defined master-pupil relationships, and the pres 221 B.C. a decline in the cultural supremacy of Alex ervation of texts and three-dimensional models had been andria set in. Intellectual life moved to more energetic aided by the growth of libraries. Yet this evidence should centers such as Pergamum, Rhodes, and above all Rome, not be interpreted to suggest that the Greek contribution but this promoted the diffusion and development of to cartography in the early Roman world was merely a Greek knowledge about maps rather than its extinction. -

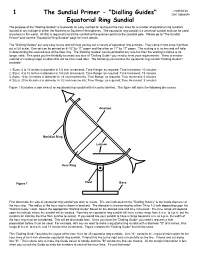

"Dialling Guides" Equatorial Ring Sundial

created by 1 The Sundial Primer - "Dialling Guides" Carl Sabanski Equatorial Ring Sundial The purpose of the "Dialling Guides" is to provide an easy method for laying out the hour lines for a number of equatorial ring sundials located at any latitude in either the Northern or Southern Hemispheres. The equatorial ring sundial is a universal sundial and can be used anywhere in the world. All that is required is to tilt the sundial so the gnomon points to the celestial pole. Please go to "The Sundial Primer" and visit the "Equatorial Ring Sundial" page for more details. The "Dialling Guides" are very easy to use and will help you lay out a variety of equatorial ring sundials. They come in two sizes if printed out at full scale. One set can be printed on 8-1/2" by 11" paper and the other on 11" by 17" paper. The scaling is in inches and will help in determining the required size of the hour ring. The "Dialling Guides" can be printed to any size but then the scaling in inches is no longer valid. This gives you the flexibility to create any size of "Dialling Guide" you need to meet your requirements. There is another method of creating larger sundials that will be discussed later. The following summarizes the equatorial ring sundial "Dialling Guides" available: 1. Sizes: 4 to 10 inches in diameter in 1/4 inch increments; Time Range: as required; Time Increment: 10 minutes 2. Sizes: 4 to 10 inches in diameter in 1/4 inch increments; Time Range: as required; Time Increment: 15 minutes 3. -

User Guide 2.0

NORTH CELESTIAL POLE Polaris SUN NORTH POLE E Q U A T O R C SOUTH POLE E L R E S T I A L E Q U A T O EARTH’S AXIS EARTH’S SOUTH CELESTIAL POLE USER GUIDE 2.0 WITH AN INTRODUCTION 23.45° TO THE MOTIONS OF THE SKY meridian E horizon W rise set Celestial Dynamics Celestial Dynamics CelestialCelestial Dynamics Dynamics CelestialCelestial Dynamics Dynamics 2019 II III Celestial Dynamics Celestial Dynamics FULLSCREEN CONTENTS SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS VI SKY SETTINGS 24 CONSTELLATIONS 24 HELP MENU INTRODUCTION 1 ZODIAC 24 BASIC CONCEPTS 2 CONSTELLATION NAMES 24 CENTRED ON EARTH 2 WORLD CLOCKASTRONOMYASTROLOGY MINIMAL STAR NAMES 25 SEARCH LOCATIONS THE CELESTIAL SPHERE IS LONG EXPOSURE 25 A PROJECTION 2 00:00 INTERSTELLAR GAS & DUST 25 A FIRST TOUR 3 EVENTS & SKY GRADIENT 25 PRESETS NOTIFICATIONS LOOK AROUND, ZOOM IN AND OUT 3 GUIDES 26 SEARCH LOCATIONS ON THE GLOBE 4 HORIZON 26 CENTER YOUR VIEW 4 SKY EARTH SOLAR PLANET NAMES 26 SYSTEM ABOUT & INFO FULLSCREEN 4 CONNECTIONS 26 SEARCH LOCATIONS TYPING 5 CELESTIAL RINGS 27 ADVANCED SETTINGS FAVOURITES 5 EQUATORIAL COORDINATES 27 QUICK START QUICK VIEW OPTIONS 6 FAVOURITE LOCATIONS ORBITS 27 VIEW THE USER INTERFACE 7 EARTH SETTINGS 28 GEOCENTRIC HOW TO EXIT 7 CLOUDS 28 SCREENSHOT PRESETS 8 HI -RES 28 POSITION 28 HELIOCENTRIC WORLD CLOCK 9 COMPASS CELESTIAL SPHERE SEARCH LOCATIONS TYPING 10 THE MOON 29 FAVOURITES 10 EVENTS & NOTIFICATIONS 30 ASTRONOMY MODE 15 SETTINGS 31 VISUAL SETTINGS ASTROLOGY MODE 16 SYSTEM NOTIFICATIONS 31 IN APP NOTIFICATIONS 31 MINIMAL MODE 17 ABOUT 32 THE VIEWS 18 ADVANCED SETTINGS 32 SKY VIEW 18 COMPASS ON / OFF 19 ASTRONOMICAL ALGORITHMS 33 EARTH VIEW 20 SCREENSHOT 34 CELESTIAL SPHERE ON / OFF 20 HELP 35 TIME CONTROL SOLAR SYSTEM VIEW 21 FINAL THOUGHTS 35 GEOCENTRIC / HELIOCENTRIC 21 TROUBLESHOOTING 36 VISUAL SETTINGS 22 CONTACT 37 CLOCK SETTINGS 22 ASTRONOMICAL CONCEPTS 38 ECLIPTIC CLOCK FACE 22 EQUATORIAL CLOCK FACE 23 IV V INTRODUCTION SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS The Cosmic Watch is a virtual planetarium on your mobile device. -

Armillary Sphere

Armillary Sphere Inventory no. 45453 Armillary sphere Armillary sphere for demonstration of the heavenly spheres made and signed by Carlo Plato, Rome, c.1588. The armillary sphere is an instrument that extends right back to the ancients, and was certainly in used by the second-century astronomer and mathematician Claudius Ptolemy, of Alexandria. It was a mathematical instrument designed to demonstrate the movement of the celestial sphere about a stationary Earth at its centre. The concept of the celestial sphere was fundamental to astronomy from Antiquity through the Middle Ages and into the Early-Modern era. At the centre of the sphere is the Earth. As the Earth is stationary in this model, it is the celestial sphere which rotates about it and acts as a reference system for locating the celestial bodies – stars, in particular – from a geocentric perspective. The instrument survived throughout the medieval period into the early modern era, and in many respects came to symbolise the queen of the sciences, astronomy. It wasn’t until the middle of the sixteenth-century that the basis of the instrument – a geocentric concept of the Universe – was seriously challenged by the Polish mathematician, Nicolaus Copernicus. Even then, the instrument still continued to serve a useful purpose as a purely mathematical instrument. Portrait of Nicolas Copernicus 1580 Held stationary at the centre is a small brass sphere representing the Earth. About it rotate a set of rings representing the heavens – the celestial sphere – one complete revolution approximating to a day or 24 hours. The sphere is mounted at the celestial poles which define the axis of rotation, and its structure includes an equatorial ring and, parallel to this, above and below, two smaller rings representing the Tropic of Cancer to the north, and the Tropic of Capricorn to the south. -

Astronomy 113 Laboratory Manual

UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN - MADISON Department of Astronomy Astronomy 113 Laboratory Manual Fall 2011 Professor: Snezana Stanimirovic 4514 Sterling Hall [email protected] TA: Natalie Gosnell 6283B Chamberlin Hall [email protected] 1 2 Contents Introduction 1 Celestial Rhythms: An Introduction to the Sky 2 The Moons of Jupiter 3 Telescopes 4 The Distances to the Stars 5 The Sun 6 Spectral Classification 7 The Universe circa 1900 8 The Expansion of the Universe 3 ASTRONOMY 113 Laboratory Introduction Astronomy 113 is a hands-on tour of the visible universe through computer simulated and experimental exploration. During the 14 lab sessions, we will encounter objects located in our own solar system, stars filling the Milky Way, and objects located much further away in the far reaches of space. Astronomy is an observational science, as opposed to most of the rest of physics, which is experimental in nature. Astronomers cannot create a star in the lab and study it, walk around it, change it, or explode it. Astronomers can only observe the sky as it is, and from their observations deduce models of the universe and its contents. They cannot ever repeat the same experiment twice with exactly the same parameters and conditions. Remember this as the universe is laid out before you in Astronomy 113 – the story always begins with only points of light in the sky. From this perspective, our understanding of the universe is truly one of the greatest intellectual challenges and achievements of mankind. The exploration of the universe is also a lot of fun, an experience that is largely missed sitting in a lecture hall or doing homework.