Disaggregating Beef Demand: Data Limitations and Industry Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to Identifying Meat Cuts

THE GUIDE TO IDENTIFYING MEAT CUTS Beef Eye of Round Roast Boneless* Cut from the eye of round muscle, which is separated from the bottom round. Beef Eye of Round Roast Boneless* URMIS # Select Choice Cut from the eye of round muscle, which is Bonelessseparated from 1the480 bottom round. 2295 SometimesURMIS referred # to Selectas: RoundChoic Eyee Pot Roast Boneless 1480 2295 Sometimes referred to as: Round Eye Pot Roast Roast, Braise,Roast, Braise, Cook in LiquidCook in Liquid BEEF Beef Eye of Round Steak Boneless* Beef EyeSame of muscle Round structure Steak as the EyeBoneless* of Round Roast. Same muscleUsually structure cut less than1 as inch the thic Eyek. of Round Roast. URMIS # Select Choice Usually cutBoneless less than1 1inch481 thic 2296k. URMIS #**Marinate before cooking Select Choice Boneless 1481 2296 **Marinate before cooking Grill,** Pan-broil,** Pan-fry,** Braise, Cook in Liquid Beef Round Tip Roast Cap-Off Boneless* Grill,** Pan-broil,** Wedge-shaped cut from the thin side of the round with “cap” muscle removed. Pan-fry,** Braise, VEAL Cook in Liquid URMIS # Select Choice Boneless 1526 2341 Sometimes referred to as: Ball Tip Roast, Beef RoundCap Off Roast, Tip RoastBeef Sirloin Cap-Off Tip Roast, Boneless* Wedge-shapedKnuckle Pcuteeled from the thin side of the round with “cap” muscle removed. Roast, Grill (indirect heat), Braise, Cook in Liquid URMIS # Select Choice Boneless Beef Round T1ip526 Steak Cap-Off 234 Boneless*1 Same muscle structure as Tip Roast (cap off), Sometimesbut cutreferred into 1-inch to thicas:k steaks.Ball Tip Roast, Cap Off Roast,URMIS # Beef Sirloin Select Tip ChoicRoast,e Knuckle PBonelesseeled 1535 2350 Sometimes referred to as: Ball Tip Steak, PORK Trimmed Tip Steak, Knuckle Steak, Peeled Roast, Grill (indirect heat), **Marinate before cooking Braise, Cook in Liquid Grill,** Broil,** Pan-broil,** Pan-fry,** Stir-fry** Beef Round Tip Steak Cap-Off Boneless* Beef Cubed Steak Same muscleSquare structureor rectangula asr-shaped. -

Meat Purchasing Guide Eighth Edition March 2019

Now contains over 700 beef, veal, lamb, mutton and pork cuts Meat purchasing guide Eighth edition March 2019 1 Contents How to use this guide 3 Quality and consistency for Link to the Cutting the meat industry Specifications on our website 4 Beef & Lamb: Higher standards, Please quote this code better returns and product name when you place your order 5 Red Tractor farm assurance or search online pigs scheme Beef 6 Beef carcase classification Each section is 7 Beef index colour-coded for 9 Beef cuts easy use Veal 50 Veal index 51 Veal cuts Product description and useful hints Lamb 66 Lamb carcase classification 67 Lamb index 68 Lamb cuts Mutton 92 Mutton index 92 Mutton cuts Pork 96 Pig carcase classification 97 Pork index Cutting specifications 99 Pork cuts Our website contains our entire range The information in this booklet was compiled by Dick van Leeuwen. of step-by-step cutting specifications that your supplier can use. Visit ahdb.org.uk/mpg 2 Quality and consistency for the meat industry Meeting the demands of the meat buyer Dick van Leeuwen Lifestyle changes and the increasing Born in Holland, Dick van Leeuwen did his training at the widely acclaimed demand from the discerning consumer Utrecht School of butchery and he is now acknowledged as a leading have led to tremendous changes and authority in butchery skills and meat processing. pressures on the red meat industry in Dick has worked in retail outlets, processing plants and at the Meat and terms of product integrity and Livestock Commission, where he developed many new products and consistency. -

Beef Eye Round Steak

DINE IN - CARRY OUT 2055 W. 136th Ave. Unit 154 Broomfield, CO 80023 (In King Soopers Shopping Center) Tel: (303) 252 - 1688 www.saigondragon.net online ordering: www.saigondragonco.com Open 7 Days a Week Sun. - Thu. : 10:00 a.m. - 9:00 p.m. Fri. - Sat. : 10:00 a.m. - 9:30 p.m. Absolutely No MSG Used Gift Certificates Available Party Tray Available We DELIVER ALL DAY $1.00 Delivery Charge with minimum Order of $15.00 within 4 mile Radius Additional $ 2.00 Delivery Charge Between 4 to 6 miles with Minimum Order of $25.00 . FREE FREE t King S 5 Grill Pork Crab Cheese i 2 n Soopers - u Wonton (8) I Spring Roll (2) Z with Purchase with Purchase . of $45 or more t * W. 136 Ave. S * of $25 or more Not valid with other offers No check accepted please mention coupon n Not valid with other offers o j please mention coupon when ordering e T when ordering Carry out or Delivery Only . Carry out or Delivery Only N Vietnamese Cuisine Saigon Chef's Special PHO - Rice Noodle Soup Served with Steamed or Fried Rice Very hot soup - Serve with basil leaves, SC1 Sauteed Mussels . 13.95 bean sprouts & lime SC2 Grilled Mussels in Basil Sauce . 13.95 PH1 Beef Eye Round Steak . 11.95 SC3 Chicken Lemongrass . 13.95 PH2 Beef Cube Brisket . 11.95 PH3 Beef Meatballs . 11.95 SC4 Lamb Lemongrass . 17.95 PH4 Special Combo . 12.95 SC5 Lamb in Curry Sauce . 17.95 Eye round steak, cube brisket & meatballs SC6 Lamb with Combo Veggies . -

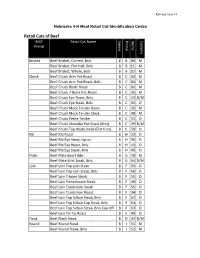

Retail Cuts of Beef BEEF Retail Cut Name Specie Primal Name Cookery Primal

Revised June 14 Nebraska 4-H Meat Retail Cut Identification Codes Retail Cuts of Beef BEEF Retail Cut Name Specie Primal Name Cookery Primal Brisket Beef Brisket, Corned, Bnls B B 89 M Beef Brisket, Flat Half, Bnls B B 15 M Beef Brisket, Whole, Bnls B B 10 M Chuck Beef Chuck Arm Pot-Roast B C 03 M Beef Chuck Arm Pot-Roast, Bnls B C 04 M Beef Chuck Blade Roast B C 06 M Beef Chuck 7-Bone Pot-Roast B C 26 M Beef Chuck Eye Roast, Bnls B C 13 D/M Beef Chuck Eye Steak, Bnls B C 45 D Beef Chuck Mock Tender Roast B C 20 M Beef Chuck Mock Tender Steak B C 48 M Beef Chuck Petite Tender B C 21 D Beef Chuck Shoulder Pot Roast (Bnls) B C 29 D/M Beef Chuck Top Blade Steak (Flat Iron) B C 58 D Rib Beef Rib Roast B H 22 D Beef Rib Eye Steak, Lip-on B H 50 D Beef Rib Eye Roast, Bnls B H 13 D Beef Rib Eye Steak, Bnls B H 45 D Plate Beef Plate Short Ribs B G 28 M Beef Plate Skirt Steak, Bnls B G 54 D/M Loin Beef Loin Top Loin Steak B F 59 D Beef Loin Top Loin Steak, Bnls B F 60 D Beef Loin T-bone Steak B F 55 D Beef Loin Porterhouse Steak B F 49 D Beef Loin Tenderloin Steak B F 56 D Beef Loin Tenderloin Roast B F 34 D Beef Loin Top Sirloin Steak, Bnls B F 62 D Beef Loin Top Sirloin Cap Steak, Bnls B F 64 D Beef Loin Top Sirloin Steak, Bnls Cap Off B F 63 D Beef Loin Tri-Tip Roast B F 40 D Flank Beef Flank Steak B D 47 D/M Round Beef Round Steak B I 51 M Beef Round Steak, Bnls B I 52 M BEEF Retail Cut Name Specie Primal Name Cookery Primal Beef Bottom Round Rump Roast B I 09 D/M Beef Round Top Round Steak B I 61 D Beef Round Top Round Roast B I 39 D Beef -

Cooking Temperatures (Oven)

Cooking Temperatures (Oven) 1. Bottom Round Roast- Bake at 325 degrees for an hour and a half or until internal temperature is 135 degrees 2. Eye Round Roast- Cook at 350 degrees F for 20 for 25 minutes per pound. 30 minutes per pound at 350 degrees F until Internal Temperatures reaches 175 degrees F 3. Top Round Roast- Bake for 15 minutes at 450 degrees. Then reduce the oven to 325 degrees and bake for an hour or until an instant read thermometer reads 135 to 140 degrees. Remove from the oven and tent with tin foil for 15 minutes. 4. Chuck Roast- Sear first! Cover and roast at 250 degrees on the center rack for 2 hours. Remove from oven and take roast from pan - best in crockpot 5. Top Sirloin Roast- Place in the oven at 375 degrees, and roast until you reach an internal temperature of 130 F for medium rare. For each additional 'step' of doneness, add ten degrees. So medium would be 140, medium-well, 150, and well-done 160. 6. Brisket- Preheat the oven or smoker to 225 degrees F. Trim the fat evenly across the top to 1/4-inch thick. Season the brisket liberally with the seasoning rub. Cook in the oven or smoker until the internal temperature on an instant- read meat thermometer reaches 175 degrees F, about 6 to 8 hours. 7. Standing Rib Roast- Bake at 350 degrees for 16 to 18 minutes a pound, to an internal temperature of 120 degrees. For a 7-pound roast, that's going to be about two hours 8. -

Uniquely Brazilian... WELCOME

WELCOME In Brazil, Picanha is the very best cut of meat, famed for its succulent texture and exceptional flavour. It’s from this celebrated cut of meat that we take our name. Picanha by Fazenda fuses the traditional gaúcho style grilling and Rodizio dining with continuous tableside service of different prime cuts of meat, including beef, chicken, pork and lamb and a gourmet salad and sides bar to accompany your meats. Let us know how you prefer your meat cooked; rare through to well done – we are happy to serve all our cuts to your taste. All our meats are served as soon as they are ready, in no particular order by our uniquely brazilian... gaúcho chefs, but please feel free to ask for your preferred cut to come out next. A glass of sparkling Jeio Prosecco on arrival, our December menu with two special meat cuts, and a dessert sharing board with petit fours. December 2018 Menu lunchtime selection JEIO PROSECCO & OUR DECEMBER SELECTION 25.60 OUR REGULAR DECEMBER SELECTION 17.90 evening selection JEIO PROSECCO & OUR DECEMBER SELECTION 36.70 OUR REGULAR DECEMBER SELECTION 28.70 VEGETARIAN / VEGAN / FISH /picanhachester lunchtime selection @picanhauk JEIO PROSECCO & OUR DECEMBER SELECTION 25.60 OUR REGULAR DECEMBER SELECTION 17.90 evening selection 01244 311839 JEIO PROSECCO & OUR DECEMBER SELECTION 28.60 [email protected] OUR REGULAR DECEMBER SELECTION 23.00 Please note that additional drinks and desserts are not included unless otherwise stated. 27 Newgate St Chester CH1 1DQ MEATS VEGETARIAN, FISH & VEGAN LUNCH DINNER picanha (Cap of rump) The beautiful cut of meat from which we take our name, Picanha, is juicy, for even more choice… choose from… full-flavoured and sure to melt in the mouth. -

Meat Quality Workshop: Know Your Muscle, Know Your Meat BEEF

2/6/2017 Meat Quality Workshop: Know Your Muscle, Know Your Meat Principles of Muscle Profiling, Aging, and Nutrition Dale R. Woerner, Ph.D., Colorado State University BEEF- Determining Value 1 2/6/2017 Slight00 Small00 Modest00 Moderate00 SLAB00 MAB00 ACE ABC Maturity Group Approximate Age A 9‐30 months B 30‐42 months C 42‐72 months D E 72‐96 months 96 months or older Augmentation of USDA Grade Application 2 2/6/2017 Effect of Marbling Degree on Probability of a Positive Sensory Experience Probability of a Positive Sensory Experience 0.99a 0.98a 1 0.88b 0.9 0.82b 0.8 0.7 0.62c 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.29d 0.3 0.2 0.15e 0.1 0 TR SL SM MT MD SA MA Colorado State University M.S. Thesis: M. R. Emerson (2011) 3 2/6/2017 Carcass Weight Trend 900 All Fed Cattle CAB® 875 850 +55 lbs. in 5 years 825 +11 lbs. / year 800 775 750 +117 lbs. in 20 years Hot Carcass (lbs.) Weight +5.8 lbs. / year 725 Year 4 2/6/2017 Further Problems • Food service portion cutting problems = 8 oz. • Steak preparation problems = 8 oz. A 1,300‐pound, Yield Grade 3 steer yields 639 pounds of retail cuts from an 806‐pound carcass. Of the retail cuts, 62% are roasts and steaks (396 pounds) and 38% are ground beef and stew meat (243 pounds). 5 2/6/2017 Objective of Innovative Fabrication • Use quality-based break points during fabrication • Add value to beef by optimizing use of high-quality cuts • Add value to beef cuts by improving leanness and portion size $2.25 $7.56 $2.75 $4.66 $2.50 $12.73 $2.31 $2.85 $3.57 $1.99 Aging Response Premium USDA Choice USDA Select Muscle Aging response -

Beef Cuts for Portioning

BEEF CUTS FOR PORTIONING CHUCK RIB LOIN SIRLOIN ROUND TOP SIRLOIN STEAK CHUCK ROLL PRIME RIB SHORT LOIN 1184 Beef Loin, Top Sirloin Butt Steak, Boneless STEAMSHIP ROUND 116A Beef Chuck, Chuck Roll 109E Beef Rib, Ribeye Roll, Lip-On, Bone In (Export Style) 174 Beef Loin, Short Loin, Short-Cut 166B Beef Round, Rump and Shank Partially Off, Handle On ORDER SPECIFICATIONS ORDER SPECIFICATIONS ORDER SPECIFICATIONS ORDER SPECIFICATIONS • Quality grade ORDER SPECIFICATIONS • Quality grade • Quality grade • Quality grade • Thickness or portion weight • Quality grade • Different arm length portion • Fat cover • Length of tail • Thickness of surface fat • Removal of shank meat exclusions - ventral cut • Weight range • Thickness of surface fat • Specify 1184A to purchase without • Thickness of surface fat • Removal of subscapularis • Thickness of surface fat • Weight range the gluteus accessorius and Portioned Top • Portion weight: 30 to 50 pounds Sirloin Steak Cooking method: Moist heat • Length of tail (lip) Cooking method: Dry heat gluteus profundus Cooking method: • Tied or netted • Specify 1184B to purchase center-cut Dry heat – roast (Cap off) – gluteus medius muscle only Cooking method: Dry heat Cooking method: Dry heat CHUCK EYE STEAK PORTERHOUSE STEAK 1116D PSO:1 Beef Chuck, Chuck Eye Roll Steak, Boneless 1173 Beef Loin, Porterhouse Steak ORDER SPECIFICATIONS RIB STEAK ORDER SPECIFICATIONS 1103 Beef Rib, Rib Steak, Bone In TOP SIRLOIN FILET • Prepared from item 116D • Quality grade 1184F Beef Loin, Top Sirloin Butt Steak, Center-Cut, Boneless, -

Order Form | Meat Department Product Name Inserts (650) | South

120 ____ BEEF PLATE BOILING BEEF 221 ____ BEEF ROUND STEAK BONELESS 121 ____ BEEF PLATE SHORT RIBS 222 ____ BEEF ROUND SIRLOIN TIP STEAK 000 ____ BEEF CHUCK ARM POT ROAST 122 ____ BEEF PLATE SPARERIBS 223 ____ BEEF ROUND TOP ROUND STEAK 001 ____ BEEF CHUCK ARM POT ROAST 123 ____ BEEF PLATE SKIRT STEAK 224 ____ BEEF ROUND BOTTOM ROUND STEAK BONELESS 124 ____ BEEF PLATE SKIRT STEAK CUBED 225 ____ BEEF ROUND EYE ROUND STEAK 002 ____ BEEF CHUCK ROUND BONE ROAST 125 ____ ROLLED BEEF PLATE BONELESS 226 ____ BEEF ROUND SWISS STEAK BONELESS 003 ____ BEEF CHUCK ROUND BONE POT ROAST 130 ____ BEEF FLANK STEAK 227 ____ BEEF ROUND TOP ROUND 004 ____ BEEF CHUCK SHOULDER ROAST LONDON BROIL 131 ____ BEEF FLANK STEAK CUBED 005 ____ BEEF CHUCK SHOULDER POT ROAST 240 ____ GROUND BEEF BONELESS 132 ____ ROLLED BEEF FLANK STEAK CUBED DOES NOT EXCEED 30% FAT 006 ____ BEEF CHUCK CLOD ROAST 133 ____ BEEF FLANK STEAK ROLLS 134 ____ BEEF FLANK LONDON BROIL 241 ____ LEAN GROUND BEEF 006-1 ____ BEEF CHUCK SHOULDER CLOD ROAST DOES NOT EXCEED 22% FAT BONELESS 140 ____ BEEF RIB ROAST 242 ____ LEANEST GROUND BEEF 007 ____ BEEF CHUCK 7- BONE ROAST 143 ____ BEEF RIB EYE ROAST DOES NOT EXCEED 15% FAT 008 ____ BEEF CHUCK BLADE ROAST 144 ____ BEEF RIB SPENCER ROAST BONELESS 243 ____ CHILI GROUND BEEF 009 ____ BEEF CHUCK TOP BLADE POT ROAST 150 ____ BEEF RIB STEAK 250 ____ BONELESS BEEF STEW 020 ____ BEEF CHUCK ROAST BONELESS 153 ____ BEEF RIB EYE STEAK 251 ____ BEEF HEARTS 021 ____ BEEF CHUCK CROSS RIB POT ROAST 153-1 ____ BEEF RIB RIB EYE STEAK BONE-IN 252 ____ BEEF MARROW -

Uniquely Brazilian... WELCOME PRICES

WELCOME In Brazil, Picanha is the very best cut of meat, famed for its succulent texture and exceptional flavour. It’s from this celebrated cut of meat that we take our name. Picanha by Fazenda fuses the traditional gaúcho style grilling and Rodizio dining with continuous tableside service of different prime cuts of meat, including beef, chicken, pork and lamb and a gourmet salad and sides bar to accompany your meats. Let us know how you prefer your meat cooked; rare through to well done – we are happy to serve all our cuts to your taste. All our meats are served as soon as they are ready, in no particular order by our uniquely brazilian... gaúcho chefs, but please feel free to ask for your preferred cut to come out next. PRICES December 2017 Menu A glass of sparkling Jeio Prosecco or Veuve Clicquot on arrival, our December menu with two special meat cuts, and a dessert sharing board with petit fours. JEIO PROSECCO LUNCH: 25.20 EVENING: 35.50 JEIO PROSECCO LUNCH: 25.20 /picanhachester VEGETARIAN/VEGAN/FISH OPTION EVENING: 30.50 @picanhauk VEUVE CLICQUOT LUNCH: 32.50 EVENING: 43.80 VEUVE CLICQUOT LUNCH: 32.50 @picanhauk VEGETARIAN/VEGAN/FISH OPTION EVENING: 38.80 Veuve Clicquot option includes a glass of dessert wine. In addition to our usual selection of meats, our December menus include a glass of 01244 311839 Jeio Prosecco or Veuve Clicquot (you will need to select which drink you wish to have [email protected] when you book your meal), and a dessert sharing board with petit fours. -

Bacon Ipsum Dolor Amet Flank Frankfurter Shankle Tenderloin Bresaola Beef Ball Tip Kielbasa Ribeye Short Loin Sirloin Pork Beef Ribs Chuck

Bacon ipsum dolor amet flank frankfurter shankle tenderloin bresaola beef ball tip kielbasa ribeye short loin sirloin pork beef ribs chuck. Pancetta short ribs jerky venison pork belly fatback capicola tri-tip cupim. Pork belly jerky strip steak filet mignon frankfurter. Short loin ham ribeye pastrami tail t-bone. Sirloin cupim chicken brisket pork loin ham hock shankle hamburger pork pork chop ham beef meatloaf sausage ribeye. Sirloin cow hamburger venison andouille. Turkey cupim bacon shank tri-tip. Tri-tip short loin turkey bacon pork chop pancetta short ribs landjaeger shankle cupim tail chuck turducken. Flank filet mignon strip steak tenderloin pork chop turkey. Tenderloin pastrami fatback, salami bacon flank kevin tail pork chop. Kielbasa shank pork meatball, cupim biltong cow filet mignon pork chop sausage. Sirloin turkey chuck tri-tip doner alcatra short ribs frankfurter flank spare ribs pig drumstick salami capicola pastrami. Doner tail swine shoulder, capicola tongue tri-tip chuck bacon beef ribs hamburger. Ribeye porchetta turducken cupim picanha. Pastrami pancetta boudin pork loin shoulder. Shoulder biltong porchetta pork belly beef. Pancetta beef ribs meatball rump boudin frankfurter swine. T-bone ribeye kevin, filet mignon short ribs bresaola strip steak beef ribs chicken. Ball tip hamburger cupim pork loin leberkas, flank pork belly drumstick. Ham hock pork pig fatback hamburger beef ribs jowl. Filet mignon kevin ham hock biltong chuck short ribs landjaeger capicola beef cow venison alcatra doner shankle pancetta. Short loin bacon andouille turducken biltong frankfurter picanha brisket drumstick pancetta tri-tip pork chop pork. Fatback beef ribs ribeye sirloin. Ground round doner cow bacon shankle strip steak. -

Specialty Products Beef Cuts for Grilling and Roasting Pork Lamb

Specialty Products PRICES GOOD WHILE SUPPLIES LAST Beef Jerky Small Package $5 German Sausage $4.99/pkg Beef Jerky Large Package $10 WOW! Jalapeno Sausage $2.99/pkg BBQ Sauce Original or Spicy $5.50 Jalapeno Cheese Sausage $4.99/pkg Cajun Fried Turkey $45/each Green Chile Cheese Sausage $4.99/pkg Spiral Sliced Honey Glazed Ham $55/each Chicken Fajita 1.5lb $7.99/pkg Variety of Seasonings Available Bratwurst $5.99/lb Beef Cuts for Grilling and Roasting 80/20 Ground Beef $4.29/lb Tenderloin Tails (Great for Grilling) $8.99/lb Stew Meat 1lb $4.99/lb NEW! Wagyu Briskets $8.99/lb Beef Plate Ribs $7.99/lb Aged Brisket (30 d+) $3.29/lb Marinated Beef Fajitas 1.5lb $15/pkg USDA Aged Prime Brisket $3.99/lb Homestyle Patties $5.29/lb Tri-Tip Roast (Boneless) $5.89/lb Chuck Roast $4.19/lb Coulotte (Picanha) $5.99/lb Steaks (All Steaks below were aged a minimum of 30 days) Premium Aged Tenderloin $32/16 oz. pkg Value Pack NY Strip $10.99/lb USDA Prime Tenderloin $44/16 oz. pkgpkg T-Bone Steaks $9.99/lb Premium Aged Ribeye (Black Label) $32/28 oz. pkgpkg USDA Prime Sirloin $16/16oz pkg Prime Ribeyes $42/28 oz. pkg Value Pack Ribeye Steak $11.99/lb USDA Prime NY Strips $36/28oz pkg WOW! USDA PRIME DRY AGED RIBEYE $19.99/lb Bone in Ribeye $12.99/lb Wagyu Ribeye Steak $50/14oz pkg Pork St. Louis Style Ribs $4.09/lb WOW! Pork Belly $1.99/lb Hickory Smoked Bacon $10.99/pkg Porterhouse Chop Thick Cut $4.99/lb Peppered Bacon $10.99/pkg Double Bone Pork Chops $4.99/lb Jalapeno Bacon $10.99/pkg Ground Pork $3.99/lb Frozen Boston Butts $1.89/lb Breakfast Sausage $4.99/lb Bone-In Pork Chops $1.99/lb Blueberry Sausage $5.99/lb Chorizo $3.99/lb Lamb Bone in Lamb Shoulder $2.99/lb Leg of Lamb, Bone-in $4.99/lb Lamb Shanks $5.99/lb Ground Lamb $3.99/lb Rack Of Lamb $15.99/lb Lamb Loin Chops $9.99/lb Discount will be taken at the register.