PERSPECTIVES on the COMPETITION 0F I4002 Dean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discovering Florence in the Footsteps of Dante Alighieri: “Must-Sees”

1 JUNE 2021 MICHELLE 324 DISCOVERING FLORENCE IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF DANTE ALIGHIERI: “MUST-SEES” In 1265, one of the greatest poets of all time was born in Florence, Italy. Dante Alighieri has an incomparable legacy… After Dante, no other poet has ever reached the same level of respect, recognition, and fame. Not only did he transform the Italian language, but he also forever altered European literature. Among his works, “Divine Comedy,” is the most famous epic poem, continuing to inspire readers and writers to this day. So, how did Dante Alighieri become the father of the Italian language? Well, Dante’s writing was different from other prose at the time. Dante used “common” vernacular in his poetry, making it more simple for common people to understand. Moreover, Dante was deeply in love. When he was only nine years old, Dante experienced love at first sight, when he saw a young woman named “Beatrice.” His passion, devotion, and search for Beatrice formed a language understood by all - love. For centuries, Dante’s romanticism has not only lasted, but also grown. For those interested in discovering more about the mysteries of Dante Alighieri and his life in Florence , there are a handful of places you can visit. As you walk through the same streets Dante once walked, imagine the emotion he felt in his everlasting search of Beatrice. Put yourself in his shoes, as you explore the life of Dante in Florence, Italy. Consider visiting the following places: Casa di Dante Where it all began… Dante’s childhood home. Located right in the center of Florence, you can find the location of Dante’s birth and where he spent many years growing up. -

Cultivating Hope

Nr. 14, April-June 2020 Cultivating hope From “The power of hope”, April, 2020 t might seem paradoxical, but this period also represents an opportunity to encounter each other again. Confined in isolation, we perhaps better understand what it means to be a community, and to be radically so. Our life does not depend solely on us and on our choices: we are all in each other’s hands, we all experience how vital interde- pendence is, a web of recognition and gift, respect and solidarity, auton- omy and relationship. Everyone has hope in each other and positively motivates one another to do their part. Everyone matters ... We are familiar with the semantics of distance and proximity and, in all truth, we need both. They are both important elements in the architecture of what we are: without one or without the other, we would not exist. Without primordial proximity we would not have been gen- erated. But even without progressive separation and distinction, our existence would also not take place. Allegory of Hope Stampe.V.102(54) It is true that in the personal and social sphere, many distances are only distorted forms of raising barriers, of inoculating the ideological vi- rus of inequality in the body of the community, of offsetting the balance of our common existence with asymmetries of every order (economic, political, cultural...). And we must also recognize that many forms of proximity are nothing more than arrogance to others, a morbid exercise of power, as if others were our property. Therefore, distance and proximi- ty must be purified. -

Images Re-Vues, 13 | 2016 the Deceptive Surface: Perception and Sculpture’S “Skin” 2

Images Re-vues Histoire, anthropologie et théorie de l'art 13 | 2016 Supports The Deceptive Surface: Perception and Sculpture’s “Skin” Illusion de surface : percevoir la « peau » d’une sculpture Christina Ferando Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/imagesrevues/3931 DOI: 10.4000/imagesrevues.3931 ISSN: 1778-3801 Publisher: Centre d’Histoire et Théorie des Arts, Groupe d’Anthropologie Historique de l’Occident Médiéval, Laboratoire d’Anthropologie Sociale, UMR 8210 Anthropologie et Histoire des Mondes Antiques Electronic reference Christina Ferando, “The Deceptive Surface: Perception and Sculpture’s “Skin””, Images Re-vues [Online], 13 | 2016, Online since 15 January 2017, connection on 30 January 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/imagesrevues/3931 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/imagesrevues.3931 This text was automatically generated on 30 January 2021. Images Re-vues est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d’Utilisation Commerciale 4.0 International. The Deceptive Surface: Perception and Sculpture’s “Skin” 1 The Deceptive Surface: Perception and Sculpture’s “Skin” Illusion de surface : percevoir la « peau » d’une sculpture Christina Ferando This paper was presented at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, as part of the symposium “Surfaces: Fifteenth – Nineteenth Centuries” on March 27, 2015. Many thanks to Noémie Étienne, organizer of the symposium, for inviting me to participate and reflect on the sculptural surface and to Laurent Vannini for the translation of this article into French. Images Re-vues, 13 | 2016 The Deceptive Surface: Perception and Sculpture’s “Skin” 2 1 Sculpture—an art of mass, volume, weight, and density. -

Sources of Donatello's Pulpits in San Lorenzo Revival and Freedom of Choice in the Early Renaissance*

! " #$ % ! &'()*+',)+"- )'+./.#')+.012 3 3 %! ! 34http://www.jstor.org/stable/3047811 ! +565.67552+*+5 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=caa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org THE SOURCES OF DONATELLO'S PULPITS IN SAN LORENZO REVIVAL AND FREEDOM OF CHOICE IN THE EARLY RENAISSANCE* IRVING LAVIN HE bronze pulpits executed by Donatello for the church of San Lorenzo in Florence T confront the investigator with something of a paradox.1 They stand today on either side of Brunelleschi's nave in the last bay toward the crossing.• The one on the left side (facing the altar, see text fig.) contains six scenes of Christ's earthly Passion, from the Agony in the Garden through the Entombment (Fig. -

Gender Dynamics in Renaissance Florence Mary D

Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal Vol. 11, No. 1 • Fall 2016 The Cloister and the Square: Gender Dynamics in Renaissance Florence Mary D. Garrard eminist scholars have effectively unmasked the misogynist messages of the Fstatues that occupy and patrol the main public square of Florence — most conspicuously, Benvenuto Cellini’s Perseus Slaying Medusa and Giovanni da Bologna’s Rape of a Sabine Woman (Figs. 1, 20). In groundbreaking essays on those statues, Yael Even and Margaret Carroll brought to light the absolutist patriarchal control that was expressed through images of sexual violence.1 The purpose of art, in this way of thinking, was to bolster power by demonstrating its effect. Discussing Cellini’s brutal representation of the decapitated Medusa, Even connected the artist’s gratuitous inclusion of the dismembered body with his psychosexual concerns, and the display of Medusa’s gory head with a terrifying female archetype that is now seen to be under masculine control. Indeed, Cellini’s need to restage the patriarchal execution might be said to express a subconscious response to threat from the female, which he met through psychological reversal, by converting the dangerous female chimera into a feminine victim.2 1 Yael Even, “The Loggia dei Lanzi: A Showcase of Female Subjugation,” and Margaret D. Carroll, “The Erotics of Absolutism: Rubens and the Mystification of Sexual Violence,” The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History, ed. Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), 127–37, 139–59; and Geraldine A. Johnson, “Idol or Ideal? The Power and Potency of Female Public Sculpture,” Picturing Women in Renaissance and Baroque Italy, ed. -

The Majolica Collection of the Museum of Bargello

The majolica collection of the Museum of Bargello A different approach to the Museum exhibition Leonardo ZAFFI, University of Florence, Department of Architecture, Italy Stefania VITI, University of Florence, Department of Architecture, Italy Keywords: Museum of Bargello, Majolica collection, design of Museums staging, resilience of Museums Introduction Nowadays the art exhibitions cannot just show the art collections, but they need to emotionally involve the visitors. The Museums users are not anymore scholars and experts only; many of them are non-specialists, wishful for evocative emotions and multi-disciplinary experiences. These new requirements, together with the need to preserve the art collections from the possible dangers (the time-effects, the natural disasters as much as human attacks), lead the new technology to play a crucial role in the design of the exhibitions layout. The design of a new art exhibition requires the involvement of many different technical and artistic knowledges. This research is focused on the design of the majolica collection exhibited at Museum of Bargello of Florence, which has been founded in 1865 as first National Museum in Italy. The Museum presents several art collections of high value, very different from each other. Even the displays exhibited at the Museum present a large variety, due to the different properties of the collections to exhibit and to the age of the staging design. Since the Museum foundation to nowadays, indeed, several displays have been followed one another, and some of them have become part of its asset. The current curators, therefore, have to deal with the double need i) to renew the exhibition, in order to guarantee the high profile of the Museum, and to optimize the expressive potentiality of each art good, and ii) to protect the art collections, providing to each item the due safety. -

Casva Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts

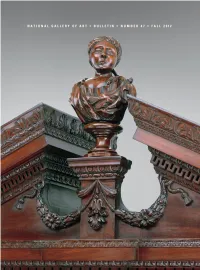

NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART • BULLETIN 34 casva Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts Collaboration, Conservation, and Context n support of its mission to gener- a volume of the National Gallery of ate new research and to promote Art’s Studies in the History of Art series, discussion of the way we think which should become an important ref- Iabout and experience art, CASVA holds erence work for scholars throughout the scholarly symposia every year. These world, including Japan. are typically highly collaborative, The findings of a similarly complex engaging both curatorial and conser- set of collaborative meetings held some vation departments, as well as other six years ago appeared in another such institutions. volume this spring. Orsanmichele and Most recently, the Center collabo- the History and Preservation of the Civic rated with colleagues to arrange a Monument (Studies in the History of series of meetings in connection with Art, volume 76), edited by Carl Brandon the exhibition Colorful Realm: Bird- Strehlke, includes papers from two sym- and-Flower Paintings by Itō Jakuchū posia, one held at the Gallery in October (1716 – 1800), which featured thirty of 2005 and the other in Florence a year Jakuchū’s scrolls from the Zen monas- later. The inspiration was again an exhi- Fig. 1. Nanni di Banco, Four Crowned tery Shōkokuji, together with his trip- bition marking the completion of a long Martyr Saints, c. 1409 – c. 1417, marble tych of the Buddha Śākyamuni. These campaign of restoration, and the loans with traces of gilding, after conserva- works of art, the subjects of long and were again made in the expectation that tion, in the exhibition Monumental careful restoration, were lent to the CASVA would bring together experts to Sculpture from Renaissance Florence: National Gallery of Art by the Imperial explore the history and conservation of Household of Japan for just one month. -

Dell' Accademia Di Palermo

DELL’ ACCADEMIA DI PALERMO DI PALERMO ACCADEMIA DELL’ DELL’ ACCADEMIA DI PALERMO CONOSCENZA, CONSERVAZIONE E DIVULGAZIONE SCIENTIFICA Musei e siti delle opere originali National Gallery of Art - Washington (D.C.) Museo dell'Hermitage di S. Pietroburgo British Museum, Londra Royal Academy, Londra Musée del Louvre di Parigi Grande Museo del Duomo - Milano Gipsoteca di Possagno Galleria degli Uffizi - Firenze Galleria dell’Accademia - Firenze Museo Nazionale del Bargello - Firenze Battistero di San Giovanni – Firenze Museo dell’Opera del Duomo - Firenze Musei Vaticani – Città del Vaticano Museo Gregoriano profano - Città del Vaticano Musei Capitolini – Roma Museo dell’Ara Pacis -Roma Museo Nazionale Romano di Palazzo Altemps, Roma Museo Nazionale Romano di Palazzo Massimo - Roma Galleria Borghese - Roma Museo Archeologico di Napoli Duomo - Monreale Galleria Interdisciplinare Regionale della Sicilia di Palazzo Abatellis - Palermo Galleria d'Arte Moderna (GAM) - Palermo Palazzo dei Normanni - Palermo Palazzo Ajutamicristo - Palermo Chiesa e Oratorio di S. Cita - Palermo Oratorio del Rosario in San Domenico - Palermo Cattedrale - Palermo Chiesa di S. Agostino - Palermo Chiesa di S. Maria della Catena - Palermo Museo Pepoli di Trapani Chiesa di S. Maria La Nova - Palermo Chiesa di Santa Maria dello Spasimo - Palermo Teatro Massimo - Palermo Palazzo Sottile - Palermo Museo Archeologico, Olimpia Palazzo della Cassa di Risparmio Vittorio Emanuele - Palermo Museo Interdisciplinare Regionale “A.Pepoli” - Trapani Museo Archeologico, Atene Museo Interdisciplinare Regionale “M. Accascina” - Messina LA GIPSOTECA DELL’ ACCADEMIA DI BELLE ARTI DI PALERMO conoscenza, conservazione e divulgazione scientifica a cura di Giuseppe Cipolla 1 fotografco di Palazzo MIUR – Ministero DIRETTORE CATALOGO RINGRAZIAMENTI dell’Istruzione, dell’Università Mario Zito a cura di Giuseppe Cipolla Abatellis, Palermo Il Direttore, i coordinatori del SOMMARIO e della Ricerca N. -

Michelangelo's David-Apollo

Michelangelo’s David-Apollo , – , 106284_Brochure.indd 2 11/30/12 12:51 PM Giorgio Vasari, Michelangelo Michelangelo, David, – Buonarroti, woodcut, from Le vite , marble, h. cm (including de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori e base). Galleria dell’Accademia, architettori (Florence, ). Florence National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, Gift of E. J. Rousuck The loan of Michelangelo’s David-Apollo () from a sling over his shoulder. The National Gallery of Art the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, to the owns a fteenth-century marble David, with the head of National Gallery of Art opens the Year of Italian Culture, Goliath at his feet, made for the Martelli family of Flor- . This rare marble statue visited the Gallery once ence (. ). before, more than sixty years ago, to reafrm the friend- In the David-Apollo, the undened form below the ship and cultural ties that link the peoples of Italy and right foot plays a key role in the composition. It raises the United States. Its installation here in coincided the foot, so that the knee bends and the hips and shoul- with Harry Truman’s inaugural reception. ders shift into a twisting movement, with the left arm The ideal of the multitalented Renaissance man reaching across the chest and the face turning in the came to life in Michelangelo Buonarroti ( – ), opposite direction. This graceful spiraling pose, called whose achievements in sculpture, painting, architecture, serpentinata (serpentine), invites viewers to move and poetry are legendary (. ). The subject of this around the gure and admire it from every angle. Such statue, like its form, is unresolved. -

Allegory of Love C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Sixteenth Century Workshop of Titian Italian 15th/16th Century Titian Venetian, 1488/1490 - 1576 Allegory of Love c. 1520/1540 oil on canvas overall: 91.4 x 81.9 cm (36 x 32 1/4 in.) Samuel H. Kress Collection 1939.1.259 ENTRY Ever since 1815, when it was discovered by Count Leopoldo Cicognara in the attic of a palace in Ferrara, the picture has attracted controversy with regard both to its attribution and to its subject. [1] Cicognara, a renowned antiquarian and connoisseur, had been commissioned by the Duchess of Sagan to find works by Titian for her, and he was convinced that his discovery was autograph. His friend Stefano Ticozzi agreed, and went on to identify the figures as Alfonso d’Este, Duke of Ferrara, and his mistress (later wife), Laura Dianti, partly on the basis of the Ferrarese provenance, partly on a supposed resemblance of the male figure to known portraits of Alfonso, and partly on the report by Giorgio Vasari that Titian had painted a portrait of Laura. [2] With these credentials, Cicognara sold the picture (together with Titian’s Self-Portrait now in Berlin) to Lord Stewart, British ambassador to the imperial court in Vienna and lover of the Duchess of Sagan. But Stewart was advised by the Milanese dealer Gerli that both pictures were copies, and he accordingly had them sent to Rome to be appraised by the Accademia di San Luca. The academicians pronounced the Self-Portrait to be authentic, but because of the presence of retouching (“alcuni ritocchi”) on the other picture, they Allegory of Love 1 © National Gallery of Art, Washington National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Sixteenth Century were unable to decide between Giorgione and Paris Bordone. -

Location Reservations Website Opening Ownership

Portrait Firenze is part of the Lungarno Collection LOCATION Just a stone’s throw from the city centre and the main fashion boutiques, looking out over the Arno and the Ponte Vecchio, sits Portrait Firenze, the hotel part of the Lungarno Collection, the hotel management company owned by the Ferragamo family. The exclusive “residence” pays homage to the city of Florence and paints a portrait of it at a very special time – the fabulous Fifties – a time that saw the birth of Italian high fashion precisely in this area of the city. RESERVATIONS +39 055 2726.4000 WEBSITE lungarnocollection.com OPENING 2014 OWNERSHIP Lungarno Collection, Hotel Management Company Property of the Ferragamo Family DESIGN Architect Michele Bönan, Planner and Interior Designer MEMBERSHIP Leading Hotels of the World DESCRIPTION “Portrait is a means, a philosophy, a new style of hospitality. In this incredibly exclusive location, swathed in comfort and elegance, the real bonus is the extraordinary team who magically manages to use this exclusiveness to make all the elements that it consists of vibrantly potent, offering far much more than the usual tailor-made services offered by a deluxe hotel,” says Valeriano Antonioli, the Lungarno Collection CEO. The first Portrait hotel in the Lungarno Collection was established in Rome in the shape of a luxury Italian residence, where the warm and heartening welcome, personalised service and emphasis on establishing a one-to-one relationship make guests feel instantly at home. The name itself – Portrait – expresses the concept of tailor-made hospitality, as if it somehow reflects a portrait of each and every guest. -

Donatello, Michelangelo, and Bernini: Their

DONATELLO, MICHELANGELO, AND BERNINI: THEIR UNDERSTANDING OF ANTIQUITY AND ITS INFLUENCE ON THE REPRESENTATION OF DAVID by Kathryn Sanders Department of Art and Art History April 7, 2020 A thesis submitted to the Honors Council of the University of the Colorado Dr. Robert Nauman honors council representative, department of Art and Art History Dr. Fernando Loffredo thesis advisor, department of Art and Art History Dr. Sarah James committee member, department of Classics TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………..……………….……………1 Chapter I: The Davids…………………………………………………..…………………5 Chapter II: Antiquity and David…………………………………………………………21 CONCLUSION………………...………………………………………………………………...40 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………………………………..58 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Donatello, David, 1430s……………………………………………………………….43 Figure 2: Michelangelo, David, 1504……………………………………………………………44 Figure 3: Bernini, David, 1624…………………………………………………………………..45 Figure 4: Donatello, David, 1408-1409………………………………………………………….46 Figure 5: Taddeo Gaddi, David, 1330…………………………………………………………...47 Figure 6: Donatello, Saint Mark, 1411…………………………………………………………..48 Figure 7: Andrea del Verrocchio, David, 1473-1475……………………………………………49 Figure 8: Bernini, Monsignor Montoya, 1621-1622……………………………………………..50 Figure 9: Bernini, Damned Soul, 1619…………………………………………………………..51 Figure 10: Annibale Carracci, Polyphemus and Acis, 1595-1605……………………………….52 Figure 11: Anavysos Kouros, 530 BCE………………………………………………………….53 Figure 12: Polykleitos, Doryphoros, 450-440 BCE……………………………………………..54 Figure 13: Praxiteles, Hermes and Dionysus, 350-330 BCE…………………………………….55 Figure 14: Myron, Discobolus, 460-450 BCE…………………………………………………...56 Figure 15: Agasias, Borghese Gladiator, 101 BCE……………………………………………...57 Introduction “And there came out from the camp of the Philistines a champion named Goliath, of Gath, whose height was six cubits and a span. He had a helmet of bronze on his head, and he was armed with a coat of mail; the weight of the coat was five thousand shekels of bronze.