Taxonomy of Duckweeds (Lemnaceae), Potential New Crop Plants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparison of Swamp Forest and Phragmites Australis

COMPARISON OF SWAMP FOREST AND PHRAGMITES AUSTRALIS COMMUNITIES AT MENTOR MARSH, MENTOR, OHIO A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Jenica Poznik, B. S. ***** The Ohio State University 2003 Master's Examination Committee: Approved by Dr. Craig Davis, Advisor Dr. Peter Curtis Dr. Jeffery Reutter School of Natural Resources ABSTRACT Two intermixed plant communities within a single wetland were studied. The plant community of Mentor Marsh changed over a period of years beginning in the late 1950’s from an ash-elm-maple swamp forest to a wetland dominated by Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steudel. Causes cited for the dieback of the forest include salt intrusion from a salt fill near the marsh, influence of nutrient runoff from the upland community, and initially higher water levels in the marsh. The area studied contains a mixture of swamp forest and P. australis-dominated communities. Canopy cover was examined as a factor limiting the dominance of P. australis within the marsh. It was found that canopy openness below 7% posed a limitation to the dominance of P. australis where a continuous tree canopy was present. P. australis was also shown to reduce diversity at sites were it dominated, and canopy openness did not fully explain this reduction in diversity. Canopy cover, disturbance history, and other environmental factors play a role in the community composition and diversity. Possible factors to consider in restoring the marsh are discussed. KEYWORDS: Phragmites australis, invasive species, canopy cover, Mentor Marsh ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A project like this is only possible in a community, and more people have contributed to me than I can remember. -

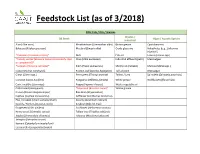

Feedstock List (As of 3/2018)

Feedstock List (as of 3/2018) FOG: Fats / Oils / Greases Wastes / Oil Seeds Algae / Aquatic Species Industrial Aloe (Aloe vera) Meadowfoam (Limnanthes alba) Brown grease Cyanobacteria Babassu (Attalea speciosa) Mustard (Sinapis alba) Crude glycerine Halophytes (e.g., Salicornia bigelovii) *Camelina (Camelina sativa)* Nuts Fish oil Lemna (Lemna spp.) *Canola, winter (Brassica napus[occasionally rapa Olive (Olea europaea) Industrial effluent (palm) Macroalgae or campestris])* *Carinata (Brassica carinata)* Palm (Elaeis guineensis) Shrimp oil (Caridea) Mallow (Malva spp.) Castor (Ricinus communis) Peanut, Cull (Arachis hypogaea) Tall oil pitch Microalgae Citrus (Citron spp.) Pennycress (Thlaspi arvense) Tallow / Lard Spirodela (Spirodela polyrhiza) Coconut (Cocos nucifera) Pongamia (Millettia pinnata) White grease Wolffia (Wolffia arrhiza) Corn, inedible (Zea mays) Poppy (Papaver rhoeas) Waste vegetable oil Cottonseed (Gossypium) *Rapeseed (Brassica napus)* Yellow grease Croton megalocarpus Oryza sativa Croton ( ) Rice Bran ( ) Cuphea (Cuphea viscossisima) Safflower (Carthamus tinctorius) Flax / Linseed (Linum usitatissimum) Sesame (Sesamum indicum) Gourds / Melons (Cucumis melo) Soybean (Glycine max) Grapeseed (Vitis vinifera) Sunflower (Helianthus annuus) Hemp seeds (Cannabis sativa) Tallow tree (Triadica sebifera) Jojoba (Simmondsia chinensis) Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) Jatropha (Jatropha curcas) Calophyllum inophyllum Kamani ( ) Lesquerella (Lesquerella fenderi) Cellulose Woody Grasses Residues Other Types: Arundo (Arundo donax) Bagasse -

C12) United States Patent (IO) Patent No.: US 10,011,854 B2 San Et Al

I 1111111111111111 1111111111 11111 1111111111 11111 1111111111111111 IIII IIII IIII US010011854B2 c12) United States Patent (IO) Patent No.: US 10,011,854 B2 San et al. (45) Date of Patent: Jul. 3, 2018 (54) FATTY ACID PRODUCTIVITY WO W02012052468 4/2012 WO WO 2012-087963 * 6/2012 (71) Applicant: WILLIAM MARSH RICE WO WO 2012-109221 * 8/2012 WO W02013059218 4/2013 UNIVERSITY, Houston, TX (US) WO W02013096665 6/2013 (72) Inventors: Ka-Yiu San, Houston, TX (US); Wei OTHER PUBLICATIONS Li, Houston, TX (US) Whisstock et al. Quaterly Reviews of Biophysics, 2003, "Prediction (73) Assignee: William Marsh Rice University, of protein function from protein sequence and structure", 36(3): Houston, TX (US) 307-340.* Witkowski et al. Conversion of a beta-ketoacyl synthase to a ( *) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term ofthis malonyl decarboxylase by replacement of the active-site cysteine patent is extended or adjusted under 35 with glutamine, Biochemistry. Sep. 7, 1999;38(36)11643-50.* U.S.C. 154(b) by O days. Kisselev L., Polypeptide release factors in prokaryotes and eukaryotes: same function, different structure. Structure, 2002, vol. 10: 8-9.* (21) Appl. No.: 15/095,158 Gurvitz Aner, The essential mycobacterial genes, fabG 1 and fabG4, encode 3-oxoacyl-thioester reductases that are functional in yeast (22) Filed: Apr. 11, 2016 mitochondrial fatty acid synthase type 2, Mo! Genet Genomics (2009), 282: 407-416.* (65) Prior Publication Data Bergler H, et a., Protein EnvM is the NADH-dependent enoyl-ACP reductase (Fahl) of Escherichia coli, J Biol Chem. 269(8):5493-6 US 2016/0215309 Al Jul. -

Introduction to Common Native & Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska

Introduction to Common Native & Potential Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska Cover photographs by (top to bottom, left to right): Tara Chestnut/Hannah E. Anderson, Jamie Fenneman, Vanessa Morgan, Dana Visalli, Jamie Fenneman, Lynda K. Moore and Denny Lassuy. Introduction to Common Native & Potential Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska This document is based on An Aquatic Plant Identification Manual for Washington’s Freshwater Plants, which was modified with permission from the Washington State Department of Ecology, by the Center for Lakes and Reservoirs at Portland State University for Alaska Department of Fish and Game US Fish & Wildlife Service - Coastal Program US Fish & Wildlife Service - Aquatic Invasive Species Program December 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ............................................................................ x Introduction Overview ............................................................................. xvi How to Use This Manual .................................................... xvi Categories of Special Interest Imperiled, Rare and Uncommon Aquatic Species ..................... xx Indigenous Peoples Use of Aquatic Plants .............................. xxi Invasive Aquatic Plants Impacts ................................................................................. xxi Vectors ................................................................................. xxii Prevention Tips .................................................... xxii Early Detection and Reporting -

Phylogeny and Systematics of Lemnaceae, the Duckweed Family

Systematic Botany (2002), 27(2): pp. 221±240 q Copyright 2002 by the American Society of Plant Taxonomists Phylogeny and Systematics of Lemnaceae, the Duckweed Family DONALD H. LES,1 DANIEL J. CRAWFORD,2,3 ELIAS LANDOLT,4 JOHN D. GABEL,1 and REBECCA T. K IMBALL2 1Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Connecticut, Storrs, Connecticut 06269-3043; 2Department of Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal Biology, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 43210; 3Present address: Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, The University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 66045-2106; 4Geobotanisches Institut ETH, ZuÈ richbergstrasse 38, CH-8044, ZuÈ rich, Switzerland Communicating Editor: Jeff H. Rettig ABSTRACT. The minute, reduced plants of family Lemnaceae have presented a formidable challenge to systematic inves- tigations. The simpli®ed morphology of duckweeds has made it particularly dif®cult to reconcile their interspeci®c relation- ships. A comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of all currently recognized species of Lemnaceae has been carried out using more than 4,700 characters that include data from morphology and anatomy, ¯avonoids, allozymes, and DNA sequences from chloroplast genes (rbcL, matK) and introns (trnK, rpl16). All data are reasonably congruent (I(MF) , 6%) and contributed to strong nodal support in combined analyses. Our combined data yield a single, well-resolved, maximum parsimony tree with 30/36 nodes (83%) supported by bootstrap values that exceed 90%. Subfamily Wolf®oideae is a monophyletic clade with 100% bootstrap support; however, subfamily Lemnoideae represents a paraphyletic grade comprising Landoltia, Lemna,and Spirodela. Combined data analysis con®rms the monophyly of Landoltia, Lemna, Spirodela, Wolf®a,andWolf®ella. -

FDA Has No Questions

Valentina Carpio-Téllez Parabel Ltd. 7898 Headwaters Commerce Street Fellsmere, FL 32948 Re: GRAS Notice No. GRN 000742 Dear Ms. Carpio-Téllez: The Food and Drug Administration (FDA, we) completed our evaluation of GRN 000742. We received Parabel’s notice on November 8, 2017 and filed it on December 19, 2017. Parabel submitted amendments to the notice on February 19, 2018; April 16, 2018; June 12, 2018; and August 1, 2018. The amendments included revisions to the dietary exposure assessment. The subjects of the notice are duckweed powder (DWP) and degreened duckweed powder (DDWP) for use as a source of protein in food at levels ranging from 3-20%.1 The notice informs us of Parabel’s view that this use of DWP and DDWP is GRAS through scientific procedures. Our use of the terms “duckweed powder” and “degreened duckweed powder” in this letter is not our recommendation of those terms as appropriate common or usual names for declaring the substances in accordance with FDA’s labeling requirements. Under Title 21 of the United States Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 101.4, each ingredient must be declared by its common or usual name. In addition, 21 CFR 102.5 outlines general principles to use when establishing common or usual names for nonstandardized foods. Issues associated with labeling and the common or usual name of a food ingredient are under the purview of the Office of Nutrition and Food Labeling (ONFL) in the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition. The Office of Food Additive Safety (OFAS) did not consult with ONFL regarding the appropriate common or usual name for “duckweed powder” and “degreened duckweed powder.” Duckweeds are aquatic plants in the Lemnoideae subfamily of the plant family Araceae.2 The notifier intends to use multiple species from the genera Landoltia, Lemna, Wolffia, and Wolfiella.3 Although the products may derive from different duckweed species, the 1 Excluding products regulated by the United States Department of Agriculture. -

Use of Duckweed, Lemna Minor, As a Protein Feedstuff in Practical Diets for Common Carp, Cyprinus Carpio, Fry

Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 4: 105-109 (2004) Use of Duckweed, Lemna minor, as a Protein Feedstuff in Practical Diets for Common Carp, Cyprinus carpio, Fry Erdal Yılmaz1,*, øhsan Akyurt1, Gökhan Günal1 1 Mustafa Kemal University, Faculty of Fisheries and Aquaculture, 31034, Antakya, Hatay, Turkey. * Corresponding Author: Tel.: +90. 326 245 58 45/1315; Fax: +90. 326 245 58 17; Received 09 February 2005 E-mail: [email protected] Accepted 09 June 2005 Abstract The use of dried duckweed, Lemna minor, as a dietary protein source for Cyprinus carpio common carp fry reared in baskets was the topic of investigation in this study. Five diets with similar E:P ratios were fed to common carp fry with an average initial weight of 0.29 g for 90 days. A diet containing 5%, 10%, 15%, or 20% duckweed was substituted for the commercial 32% protein control-group diet, fed in normal rations to common carp. There was no significant difference between the growth performance of fish that were fed diets containing up to 20% duckweed and fish that were fed the control diet (P>0.05), except for the group of fish on the 15% duckweed diet. Also, no significant difference was observed among treatments with respect to feed utilization (P>0.05). While carcass lipid content increased, protein content of the fish fed a diet of 15% duckweed decreased compared to other groups (P<0.05). The results showed that a diet consisting of up to 20% content could be used as a complete replacement for commercial feed in diet formulation for common carp fry. -

Growth Response of Lemna Gibba L. (Duckweed) to Copper and Nickel Phytoaccumulation Effet De L’Accumulation De Cu Et Ni Sur La Croissance De Lemna Gibba L

NOVATECH 2010 Growth response of Lemna gibba L. (duckweed) to copper and nickel phytoaccumulation Effet de l’accumulation de Cu et Ni sur la croissance de Lemna gibba L. (lentilles d’eau) N. Khellaf, M. Zerdaoui Laboratory of Environmental Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Badji Mokhtar University, P.O. Box 12, 23000 Annaba, Algeria (E-mail: [email protected] (N. Khellaf); [email protected] (M. Zerdaoui)) RÉSUMÉ Pour déterminer la tolérance et la capacité de phytoaccumulation du cuivre (Cu) et du nickel (Ni) par une espèce de lentilles d’eau, Lemna gibba L., les plantes sont exposées à différentes concentrations de Cu et Ni (0,1 à 2,0 mg/L) dans une solution de Coïc et Lesaint dilué à 1/4. Le pH est maintenu constant à 6,0 (± 0,1) et le flux de lumière est de 12 h/jour. Le cuivre et le nickel sont tolérés par L. gibba à des concentrations ≤ 0,3 mg/L et ≤ 0,5 mg/L, respectivement. Cependant, la croissance des plantes diminue de 50% (I50) quand le milieu de culture contient 0,45 mg/L de Cu ou 0,75 mg/L de Ni. La plus faible concentration causant une inhibition complète (LCI) est de 0,5 et 1,0 mg/L respectivement en présence de Cu et Ni. Les résultats de l’analyse du métal dans les tissus des plantes révèlent une grande accumulation de Cu et une faible accumulation de Ni dans les tissus végétaux (pour la concentration ne causant aucune inhibition dans la croissance). Une diminution de la concentration de métal dans l’eau est également observée. -

A Preliminary List of the Vascular Plants and Wildlife at the Village Of

A Floristic Evaluation of the Natural Plant Communities and Grounds Occurring at The Key West Botanical Garden, Stock Island, Monroe County, Florida Steven W. Woodmansee [email protected] January 20, 2006 Submitted by The Institute for Regional Conservation 22601 S.W. 152 Avenue, Miami, Florida 33170 George D. Gann, Executive Director Submitted to CarolAnn Sharkey Key West Botanical Garden 5210 College Road Key West, Florida 33040 and Kate Marks Heritage Preservation 1012 14th Street, NW, Suite 1200 Washington DC 20005 Introduction The Key West Botanical Garden (KWBG) is located at 5210 College Road on Stock Island, Monroe County, Florida. It is a 7.5 acre conservation area, owned by the City of Key West. The KWBG requested that The Institute for Regional Conservation (IRC) conduct a floristic evaluation of its natural areas and grounds and to provide recommendations. Study Design On August 9-10, 2005 an inventory of all vascular plants was conducted at the KWBG. All areas of the KWBG were visited, including the newly acquired property to the south. Special attention was paid toward the remnant natural habitats. A preliminary plant list was established. Plant taxonomy generally follows Wunderlin (1998) and Bailey et al. (1976). Results Five distinct habitats were recorded for the KWBG. Two of which are human altered and are artificial being classified as developed upland and modified wetland. In addition, three natural habitats are found at the KWBG. They are coastal berm (here termed buttonwood hammock), rockland hammock, and tidal swamp habitats. Developed and Modified Habitats Garden and Developed Upland Areas The developed upland portions include the maintained garden areas as well as the cleared parking areas, building edges, and paths. -

Check List 5(2): 195–199, 2009

Check List 5(2): 195–199, 2009. ISSN: 1809-127X NOTES ON GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION Plantae, Liliopsida, Arales, Araceae, Dracontioides desciscens, Lemna aequinoctialis and Montrichardia linifera: Distribution extension and first records for state of Sergipe, Brazil José Elvino do Nascimento-Júnior Ana Paula Prata Universidade Federal de Sergipe, Centro de Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde, Departamento de Biologia. Campus Prof. José Aloísio Campos, São Cristóvão. CEP 49100-000. Aracaju, Sergipe, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected] The state of Sergipe is located in the east of This work brings information of such new Brazilian northeastern, with an area of 21,910 occurrences for Sergipe and presents, in a km2, 75 municipalities and approximately 1,7 complementary manner, a dichotomous key to the million inhabitants. The flora of Sergipe occurs aquatic species of Araceae occurring in the state. in different types of vegetation and although The distribution of species was obtained by it is in a fairly advanced stage of degradation it consulting the databases SpeciesLink (CRIA has been little studied. Among the 23 families 2008) and World Checklist of Selected Plant of monocots that occur in the state, Araceae Families (2008), as well as consultations with stand out for its wide variety of forms of life literature. The maps of distribution show points of and habitats, with some terrestrial species, living occurrence only for Brazil. Details about the directly on the soil or in crevices between rocks, occurrence in other regions are commented in the while others are aquatic fixed or floating. text. About 70 % of the species of families are epiphytes, hemiepiphytes or climbing (Grayum Dracontioides Engl. -

THE FAMILY of LEMNACEAE in VENEZUELA Acta Botanica Venezuelica, Vol

Acta Botanica Venezuelica ISSN: 0084-5906 [email protected] Universidad Central de Venezuela Venezuela LANDOLT, Elias; VELÁSQUEZ, Justiniano; LÄMMLER, Walter; GORDON, Elizabeth THE FAMILY OF LEMNACEAE IN VENEZUELA Acta Botanica Venezuelica, vol. 38, núm. 2, 2015, pp. 113-158 Universidad Central de Venezuela Caracas, Venezuela Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=86250805002 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative ACTA BOT. VENEZ. 38 (2): 113-158. 2015 113 THE FAMILY OF LEMNACEAE IN VENEZUELA La familia Lemnaceae en Venezuela Elias LANDOLT1 († 2013), Justiniano VELÁSQUEZ2, Walter LÄMMLER3 and Elizabeth GORDON2* 1 Institut für Integrative Biologie, ETH Zürich Universitätsstr 16, CH-8092, Zürich 2 Laboratorio de Ecología de Plantas Acuáticas, Centro de Ecología y Evolución, Instituto de Zoología y Ecología Tropical, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Central de Venezuela, Caracas 1041-A, A.P. 47058, Venezuela [email protected]; [email protected] (* Autor para correspondencia) 3 Landolt Duckweed Collection, Spiegelgasse 12, CH- 8001, Zürich ABSTRACT During a trip to the northern part of Venezuela in 2005 about 70 samples of Lemnaceae have been collected. Together with the results of herbaria studies it was possible to construct distribution maps of the respective Lemnaceae species in Ve ne- zuela. Fifteen species are recognized from which four have been recorded newly: Landoltia punctata, Lemna obscura, Wolffiella neotropica, Wolffia globosa. Out of these species, W. neotropica is endemic in the northeastern part of South Ame rica. -

Wetland Plants of the Townsville − Burdekin

WETLAND PLANTS OF THE TOWNSVILLE − BURDEKIN Dr Greg Calvert & Laurence Liessmann (RPS Group, Townsville) For Lower Burdekin Landcare Association Incorporated (LBLCA) Working in the local community to achieve sustainable land use THIS PUBLICATION WAS MADE POSSIBLE THROUGH THE SUPPORT OF: Burdekin Shire Council Calvert, Greg Liessmann, Laurence Wetland Plants of the Townsville–Burdekin Flood Plain ISBN 978-0-9925807-0-4 First published 2014 by Lower Burdekin Landcare Association Incorporated (LBLCA) PO Box 1280, Ayr, Qld, 4807 Graphic Design by Megan MacKinnon (Clever Tangent) Printed by Lotsa Printing, Townsville © Lower Burdekin Landcare Association Inc. Copyright protects this publication. Except for purposes permitted under the Copyright Act, reproduction by whatever means is prohibited without prior permission of LBLCA All photographs copyright Greg Calvert Please reference as: Calvert G., Liessmann L. (2014) Wetland Plants of the Townsville–Burdekin Flood Plain. Lower Burdekin Landcare Association Inc., Ayr. The Queensland Wetlands Program supports projects and activities that result in long-term benefits to the sustainable management, wise use and protection of wetlands in Queensland. The tools developed by the Program help wetlands landholders, managers and decision makers in government and industry. The Queensland Wetlands Program is currently funded by the Queensland Government. Disclaimer: This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The authors and funding bodies hold no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this document is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy.