Putting a Glitch in the Field: Music, Technology, Production

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conrad Schnitzler / Pole Con-Struct

CONRAD SCHNITZLER / POLE CON-STRUCT CD / LP (+ CD) / Digital March 24th 2017 Who is Conrad Schnitzler? Conrad Schnitzler (1937–2011), composer and concept artist, is one of the most important representatives of Germany’s electronic music avant-garde. A student of Joseph Beuys, he founded Berlin’s legendary Zodiak Free Arts Lab, a subculture club, in 1967/68, was a member of Tangerine Dream (together with Klaus Schulze and Edgar Froese) and Kluster (with Dieter Moebius and Hans-Joachim Roedelius) and also released countless solo albums. Who is Pole? The Düsseldorf-native musician, producer, remixer and mastering engineer Stefan Betke looks back on a steady two decade career in abstract electronic club music. Together with Barbara Preisinger he created the label „scape Records” and his own mastering studio „scape-mastering”. What is the concept of the Con-Struct series? Conrad Schnitzler liked to embark on daily excursions through the sonic diversity of his synthesizers. Finding exceptional sounds with great regularity, he preserved them for use in combination with each other in subsequent live performances. He thus amassed a vast sound archive of his discoveries over time. When Jens Strüver, the producer of the Con-Struct series, was granted access to this audio library at the outset of the 2010 decade, he came up with the idea of con-structing new compositions, not remixes, from the archived material. On completion of the first Con-Struct album, he decided to develop the concept into a series, with different electronic musicians invited into Schnitzler’s unique world of sound. A few words from Pole on his con-structions To be honest, in earlier times I never quite warmed to Conrad Schnitzler's work. -

Systems Music on Spiro's Pole Star

Systems music on Spiro’s Pole Star Balancing musical experiment and tradition in folk revival Gabriel Harmsen 6630030 Thesis BA Musicology MU3V14004 2019-2020, block 4 Utrecht University Supervisor: dr. Rebekah S. Ahrendt Abstract Theoretical frameworks of folk revival applied by folklorists and (ethno-)musicologists have related revival to identity formation of social groups (divided by class or race), local communities and national “imagined” communities. New theoretical models extend this framework with a transnational, post-revival perspective in which the focus lies on what happens after music traditions are revived. Instead of playing arbiter between “authentic” and imagined/reconstructed music practices, artists and scholars now re-explore creative balances between tradition/innovation, national/international, past/future, and even low/high art. Progressive revival genres have abandoned the concern for “authenticity” by merging traditional and modern musical idioms. Nonetheless, modern folk artists remain connected to an initial revival impulse because they depend on its commercial infrastructure and musical source material. In this thesis I investigate the combination of British traditional music and American minimalism through the post-revival lens. A case study of the album Pole Star by English folk band Spiro demonstrates what compositional techniques of systems music play a role in Spiro’s arrangements, and how they interact with historical melodies. The analysis exposes what musical characteristics of these opposite worlds blend together, coexist or clash with one another. The extended length and lyrical characteristic of historical melodies prove to be crucial factors in determining the crossroad between tradition and modernity in Spiro’s approach. 2 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………. -

Pole Steingarten Mp3, Flac, Wma

Pole Steingarten mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Steingarten Country: Germany Released: 2007 Style: Minimal, Abstract, Dub, Experimental MP3 version RAR size: 1920 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1205 mb WMA version RAR size: 1155 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 626 Other Formats: ADX MOD MP1 AAC MP2 MIDI MP4 Tracklist 1 Warum 4:58 2 Winkelstreben 5:04 3 Sylvenstein 5:08 4 Schöner Land 3:39 5 Mädchen 5:38 6 Achterbahn 4:55 7 Düsseldorf 4:24 8 Jungs 7:15 9 Pferd 4:13 Companies, etc. Distributed By – Indigo – 82439-2 Distributed By – MDM – 1044-2 Manufactured By – Optimal Media Production – A675822 Phonographic Copyright (p) – ~scape Copyright (c) – ~scape Published By – Scape Publishing Published By – BMG Music Publishing Germany Recorded At – Scape Studio, Berlin Recorded At – Scape Rock Garden Mastered At – Scape Mastering Credits Design – Julia Vietense Photography By – Kienberger, Lechbruck* Written-By, Producer – Stefan Betke Notes Recorded at Scape Studio Berlin. Additional Recordings at Scape Rock Garden. Mastered at Scape Mastering Berlin. Published by Scape Publishing / BMG Music Publ. Germany. p c ~scape, 2007. Issued in a slimline jewel case with J-card insert. "For promotional use only" printed on back of insert and CD. Enhancement includes (named "promo cd extras"): info, bio, cover jpg, artist pictures Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout: A675822-01 manufactured by optimal media production INDIGO CD 82439-2 Mastering SID Code: ifpi L572 Mould SID Code: IFPI 9713 Label Code: lc10562 Other versions -

'Musical Pitch Ought to Be One from Pole to Pole': Touring Musicians and the Issue of Performing Pitch in Late Nineteenth

2011 © Simon Purtell, Context 35/36 (2010/2011): 111–25. ‘Musical Pitch ought to be One from Pole to Pole’: Touring Musicians and the Issue of Performing Pitch in Late Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-century Melbourne Simon Purtell In 1869, English vocal teacher Charles Bishenden complained that the high performing pitch in use in England was ‘ruinous to the voice.’ The high pitch, he reported, was the very reason why many European singers did not perform in Britain.1 ‘For a Continental larynx,’ French soprano Blanche Marchesi (1863–1940) later explained, ‘it is a real torture to sing to different pitches.’ ‘The muscles of a trained larynx act like fine clockwork,’ she wrote, and ‘a change of tone, up or down, alters the precision of their action.’ For this reason, Marchesi believed that ‘musical pitch ought to be one from pole to pole.’2 A standard of performing pitch comprises three fundamental concepts: sound frequency, note-name, and standard. A sound frequency, expressed in Hertz (Hz) or cycles per second (cps), becomes a pitch when assigned to a note in the musical scale, thus determining the pitch of every other note in a particular system of tuning. If, in equal temperament, the A directly above middle C equals 440 Hz, then the C directly above it equals 523.25 Hz. A pitch that is agreed upon, at a given time and place, as the reference point for building and tuning musical instruments to play together, is a pitch standard. Standards of pitch are usually expressed in relation to the note A directly above middle C. -

The Antarctic Sun, December 24, 2006

December 24, 2006 HowHow McMurdo Got Its Groove On Local music scene heats up By Peter Rejcek Sun staff OTHER RIFFS t’s possibly the cool- Even Shackleton got the est music scene on the blues, page 10 planet. McMurdo Station Pole, Palmer also jam, is certainly the hub page 11 Iof operations for the U.S. AntarcticI Program (USAP) wise, this is a real hotbed of with an austral summer popu- potential.” lation of a thousand people Fox is a pretty good judge or more. But in the last 10 or of what makes a music scene 15 years, it’s become a cross- pulse. He came of age dur- roads for musicians playing ing punk rock’s angry genesis in just about every genre in the late 1970s and early imaginable in their leisure 1980s, playing bass for the time, from reggae to rock and band United Mutation in the from blues to bluegrass. It’s Washington, D.C., area. (See a scene where a punk rocker the Dec. 18, 2005, issue of can share the night’s billing The Antarctic Sun at antarc- with a folk singer and a blues ticsun.usap.gov for a related guitarist – and the audience is story.) there to see them all. A conversation with Fox is “We have been really itself like listening to a punk lucky down here,” said Jay rock set – briefly intense out- Peter Rejcek / The Antarctic Sun Fox, the retail supervisor for bursts, each riff a variation Barb Propst plays guitar at the McMurdo Station Coffee House. -

The Tim Ferriss Show Transcripts Episode 62: Justin Boreta Show Notes and Links at Tim.Blog/Podcast

The Tim Ferriss Show Transcripts Episode 62: Justin Boreta Show notes and links at tim.blog/podcast Tim Ferriss: Hello ladies and gents, this is Tim Ferriss, and welcome to another episode. God damn. That’s the usual intro music, but I’d like you to hear a brand new version, reimagined by none other than Justin Boreta of The Glitch Mob. This podcast is brought to you by Mizzen and Main. Don’t worry about the spelling. All you need to know is this. I have organized my entire life around avoiding fancy shirts, because you have to iron them, you sweat through them, they smell really easily, they’re a pain in the ass. Mizzen and Main has given me the only shirt that I need. And what I mean by that, and Kelly Starrett loves these shirts as well, is that you can trick people. They look really fancy, so you can take them out to nice dinners, whatever, but they’re made from athletic, sweat- wicking material. So you can throw this thing into your luggage in a heap or on your kitchen table like I did recently, and then pull it out, throw it on, with no ironing, no steaming, no nothing, walk out, and you could probably wear this thing for a week straight, or make it your only dress shirt, and take it on trips for weeks at a time, never wash it, it will not smell, you will not sweat through it, you’ve got to check these things out. So go to fourhourworkweek.com, all spelled out, fourhouroworkweek.com/shirts, and if you order one of their dress shirts in the next week you will get a Henley shirt for free. -

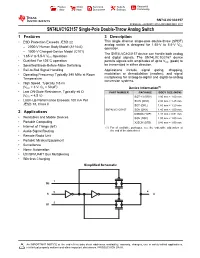

SN74LVC1G3157 Single-Pole Double-Throw Analog Switch Datasheet

Product Order Technical Tools & Support & Folder Now Documents Software Community SN74LVC1G3157 SCES424L –JANUARY 2003–REVISED MAY 2017 SN74LVC1G3157 Single-Pole Double-Throw Analog Switch 1 Features 3 Description This single channel single-pole double-throw (SPDT) 1• ESD Protection Exceeds JESD 22 analog switch is designed for 1.65-V to 5.5-V VCC – 2000-V Human Body Model (A114-A) operation. – 1000-V Charged-Device Model (C101) The SN74LVC1G3157 device can handle both analog • 1.65-V to 5.5-V VCC Operation and digital signals. The SN74LVC1G3157 device • Qualified For 125°C operation permits signals with amplitudes of up to VCC (peak) to • Specified Break-Before-Make Switching be transmitted in either direction. • Rail-to-Rail Signal Handling Applications include signal gating, chopping, • Operating Frequency Typically 340 MHz at Room modulation or demodulation (modem), and signal Temperature multiplexing for analog-to-digital and digital-to-analog conversion systems. • High Speed, Typically 0.5 ns (VCC = 3 V, CL = 50 pF) Device Information(1) • Low ON-State Resistance, Typically ≉6 Ω PART NUMBER PACKAGE BODY SIZE (NOM) (VCC = 4.5 V) SOT-23 (DBV) 2.90 mm × 1.60 mm • Latch-Up Performance Exceeds 100 mA Per SC70 (DCK) 2.00 mm × 1.25 mm JESD 78, Class II SOT (DRL) 1.60 mm × 1.20 mm SN74LVC1G3157 SON (DRY) 1.45 mm × 1.00 mm 2 Applications DSBGA (YZP) 1.41 mm × 0.91 mm • Wearables and Mobile Devices SON (DSF) 1.00 mm × 1.00 mm • Portable Computing X2SON (DTB) 0.80 mm × 1.00 mm • Internet of Things (IoT) (1) For all available packages, see the orderable addendum at • Audio Signal Routing the end of the data sheet. -

BEAUTIFUL NOISE Directions in Electronic Music

BEAUTIFUL NOISE Directions in Electronic Music www.ele-mental.org/beautifulnoise/ A WORK IN PROGRESS (3rd rev., Oct 2003) Comments to [email protected] 1 A Few Antecedents The Age of Inventions The 1800s produce a whole series of inventions that set the stage for the creation of electronic music, including the telegraph (1839), the telephone (1876), the phonograph (1877), and many others. Many of the early electronic instruments come about by accident: Elisha Gray’s ‘musical telegraph’ (1876) is an extension of his research into telephone technology; William Du Bois Duddell’s ‘singing arc’ (1899) is an accidental discovery made from the sounds of electric street lights. “The musical telegraph” Elisha Gray’s interesting instrument, 1876 The Telharmonium Thaddeus Cahill's telharmonium (aka the dynamophone) is the most important of the early electronic instruments. Its first public performance is given in Massachusetts in 1906. It is later moved to NYC in the hopes of providing soothing electronic music to area homes, restaurants, and theatres. However, the enormous size, cost, and weight of the instrument (it weighed 200 tons and occupied an entire warehouse), not to mention its interference of local phone service, ensure the telharmonium’s swift demise. Telharmonic Hall No recordings of the instrument survive, but some of Cahill’s 200-ton experiment in canned music, ca. 1910 its principles are later incorporated into the Hammond organ. More importantly, Cahill’s idea of ‘canned music,’ later taken up by Muzak in the 1960s and more recent cable-style systems, is now an inescapable feature of the contemporary landscape. -

North Pole Folio Album

North Pole Folio Album This folio measures 7 1/2 x 9 with a 1 1/2 spine, and uses the Simple Stories Snap pages incorporated in the design of the folio. This folio can hold up to 80 photos, and is decorated with nothing but scraps left over from a collection of papers. 1 | P a g e January 2021 Scrappin It Up By: Vanessa Peter Supplies Used Kraft Cardstock – Hobby Lobby 65lb Vintage North Pole Collection Simple Stories – Just used scraps to decorate this folio Simple Stories Snap Pages – 4 of them Score-pal tape – double sided tape/glue Cutting Guide Spine Hinges 3 – 1 1/2 x 9 score on the 1 1/2 side at 1/2 & 1 Snap Page Hinges 2 – 4 1/2 x 8 1/2 score on the 4 1/2 side at 3/4, 1, 1 1/2, 2, 2 1/4, 2 1/2, 3, 3 1/2, 3 3/4 Covers 2 – 7 1/2 x 9 2 – 7 1/2 x 10 score on the 10 side at 1/2 on each end Cover Flaps 2 – 9 x 12 score on the 12 side at 3/4, 1 1/8, 1 1/2, 8 1/8 Inside Front/Back Cover Flaps 2 – 6 1/2 x 9 score on the 6 1/2 side at 1/2 2 – 6 1/2 x 6 1/2 score on just one 6 1/2 side Backside of Right/Left Pocket Page 4 – 7 x 9 score on the 7 side at 1/2 2 | P a g e January 2021 Scrappin It Up By: Vanessa Peter Inside Pocket Pages 2 – 7 x 9 2 – 5 x 10 score on the 10 side at 1/2 on each end Pocket Page Flap 2 – 6 x 7 1/2 score on the 6 side at 1/2 Slanted Pocket 2 – 5 1/2 x 6 score 1/2 just on 2 sides, depending on which side the pocket is placed on. -

Palaeontologia Electronica EARLY EOCENE DISPERSED CUTICLES

Palaeontologia Electronica http://palaeo-electronica.org EARLY EOCENE DISPERSED CUTICLES AND MANGROVE TO RAINFOREST VEGETATION AT STRAHAN-REGATTA POINT, TASMANIA Mike Pole Mike Pole. Queensland Herbarium, Toowong, Qld 4066, Australia. [email protected] ABSTRACT Early Eocene plant-fossil assemblages (mostly of dispersed cuticle) from Strahan- Regatta Point, Tasmania, Australia, record evidence of mesothermal rainforest (mean annual temperatures between 12 and 20ºC) and mangrove vegetation surrounding an estuary, which grew close to the polar circle. Plant taxa represented by cuticle include: Bowenia (Cycadales), conifers, including Acmopyle, Agathis, Araucaria, Dacrycarpus, Libocedrus, Prumnopitys, and a gnetalean. Fifty- five taxa of angiosperms are recogn- ised from cuticle, including Winteraceae, 11 Lauraceae (including an unusual toothed species) and seven Proteaceae as well as Gymnostoma, Aquifoliaceae, and Rhipogo- naceae. There is also a Rhizophoraceae, which is interpreted as another mangrove, in addition to the mangrove palm Nypa, which has been described previously. In an Aus- tralasian context the absence of Myrtaceae is notable. Multivariate analysis of the fossil distribution suggests that a significant amount of the variation can be attributed to whether they accumulated in the mangrove mud (or associated tidal sand flat) or in a freshwater facies. KEY WORDS: Early Eocene, cuticle, stomata, mangrove, biodiversity, paleoclimate INTRODUCTION al. 1999; Zachos et al. 2001, 2005). Today the world is also undergoing profound warming due to The Early Eocene includes two periods of glo- anthropogenic greenhouse gases (Intergovern- bally warm temperatures where thermophilic vege- mental Panel on Climate Change 2007) and under- tation (among other biota) extended its range standing the effects this will have on the biota and significantly towards the poles; these were the local climates has become a key research goal. -

"One for the Money"? Introduction

"One For The Money"? The impact of the "disk crisis" on "ordinary musicians" income: The case of French speaking Switzerland Pierre Bataille)1 et Marc Perrenoud2 1Université Grenoble-Alpes, LaRAC/LIVES 2Université de Lausanne, LACCUS/LIVES Abstract The so called "disk-crisis" and the rise of music digitization and/or music piracy regularly make the headlines of general and specialized newspapers. The impacts of these metamorphoses on the more visible actors of the national musical industries are relatively well documented. Nevertheless, little is known about the impact of these changes on the musicians’ incomes – especially the "ordinary" ones, who are located at the intermediary and the bottom stages of the professional hierarchy. This paper aims to contribute to better understanding the extent to which digitization reshaped the ways these little-known musicians make a living from music. To do so, we use longitudinal data collected from a sample of musicians active in the French-speaking part of Switzerland in the early 2010’s. These data mainly consist of life calendar-data, with retrospective information on income sources for every year of the career – from the first gig played in public to 2013. Crossing sequence analysis and geometrical data analysis tools, we analyze whether or not digitization spurred a career reorientation to one of two major "poles" structuring the "ordinary musicians" professional space (the "artist" pole or the "craftsman" one). We show that changes are few. Nevertheless, we point out how social origin and gender impact these potential career reorientations. More broadly, our paper points to the need to analyze the social conditions of appropriability of technological innovations - especially when it comes to symbolic goods. -

Press Sezione Audio

Interferenze 2005 >rumori>visioni>bit di campagna Audio ITA FRAME Il progetto Frame nasce nel 2001 nel corso della realizzazione della colonna sonora originale del film “L'Inverno” di Nina di Majo, presente alla 56esima edizione del festival del cinema di Berlino. si tratta principalmente di un progetto di sonorizzazione di immagini, che concepisce la colonna sonora come un genere musicale a parte, che propone un metodo di lavorazione originale nell'ambito delle produzioni cinematografiche e che sceglie come principale forma espressiva la musica elettronica intesa come manipolazione a più livelli di fonti sonore acustiche e sintetiche, dai suoni della realtà a quelli risultanti da qualsiasi tipo di elaborazione, proprio perché finalizzata alle immagini e in qualche modo alla ricostruzione di una realtà artificiale come quella cinematografica, la musica dei Frame si avvicina molto più all'idea di “concept sonoro” che a quella di musica tout-court. I Frame sono Davide Mastropaolo e Leandro Sorrentino, e si avvalgono a seconda del singolo progetto dell'apporto di musicisti dalle più diverse estrazioni. Nel 2002 hanno pubblicato la colonna sonora del film “L'Inverno” di Nina di Majo, prodotta dalla Cam e distribuita dalla Sony, nei cui crediti figurano tra gli altri Antonella Ruggiero e Marco Messina dei 99 Posse. I Frame hanno inoltre realizzato la colonna sonora originale dei cortometraggi “Ritratto di Bambino” di Gianluca Iodice, prodotto dalla Indigo film, “La Visita” di Andrea De Rosa, prodotto dalla Ananas film, entrambi presenti in concorso nella sezione europea alla 20esima edizione del Torino Film Festival. web: www.framebox.it MAJA RATKJE Tra gli ascolti preferiti di Motorpsycho e Thurston Moore (Sonic Youth), Maja Solveig Kjelstrup Ratkje è compositrice e performer free-lance.