Abstract Friday 10:03

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SERMON NOTES from in Touch with Dr

SERMON NOTES From In Touch With Dr. Charles Stanley The Believer’s War Room KEY PASSAGE: Matthew 6:5-6 | SUPPORTING SCRIPTURES: Proverbs 3:5-6 | Isaiah 54:17 | Ephesians 6:10-18 SUMMARY Satan is our enemy, and he’s a murderer, liar, deceiver, schemer, tempter, and destroyer. But as believers, we do What are we to do with our trials, heartaches, and not have to become his victims. God has given us the burdens? key to living in a manner that pleases and honors Him. And that key is prayer. In the war room of prayer, we fight Although many people try to bear them on their own, Jesus our battles on our knees, coming confidently and boldly has given us the solution in a passage from His Sermon on to our heavenly Father, sharing the innermost thoughts the Mount. He says to go into an inner room, close the door, of our hearts, knowing that He hears and intervenes on and pray to our Father in heaven. All of us need to learn our behalf. how to talk to the Lord in private about whatever concerns us. And sometimes that inner room becomes our war room Jesus spoke of a place of prayer. as we fight our battles with sin, conflicts, decisions, and difficulties until we fully surrender in obedience to our God. Because He lived an itinerant lifestyle, Christ’s place of prayer changed as He traveled, but prayer was always a SERMON POINTS priority in His life and should be in ours as well. According to Ephesians 6:10-13, believers are in a struggle— It’s a private place. -

LWF Council Worship

Liturgy and Worship “Freely you have received, freely give.” – Matthew 10:8 (NIV) 2018 Council Meeting Ecumenical Centre, Geneva, Switzerland 27 June – 2 July, 2018 Morning Prayer, Wednesday 27 June This week in the ecumenical prayer cycle, we pray for Kenya and Tanzania We open with the sound of a gong We sing (1st verse in Swahili) Liturgist: Ms Desri Sumbayak, The Indonesian Christian Church Psalm 18: God my friend, You give me strength. God, my shield, my help, You watch over me. You bring me out into a broad place Because you delight in me. It is you who light my lamp. You light up my darkness. By you, God, I can leap over a wall. For this I will extol you in the morning and in the evening, now and always. Amen. Scripture reading: Mark 4:35-41 On that day, when evening had come, he said to them, “Let us go across to the other side.” And leaving the crowd behind, they took him with them in the boat, just as he was. Other boats were with him. A great windstorm arose, and the waves beat into the boat, so that the boat was already being swamped. But he was in the stern, asleep on 2 the cushion; and they woke him up and said to him, “Teacher, do you not care that we are perishing?” He woke up and rebuked the wind, and said to the sea, “Peace! Be still!” Then the wind ceased, and there was a dead calm. He said to them, “Why are you afraid? Have you still no faith?” And they were filled with great awe and said to one another, “Who then is this, that even the wind and the sea obey him?” Meditation Prayers The night has passed, and the day lies open before us; let us pray with one heart and mind. -

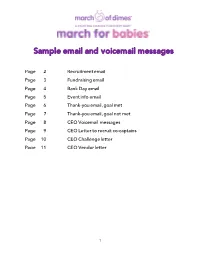

Sample Email and Voicemail Messages

Sample email and voicemail messages Page 2 Recruitment email Page 3 Fundraising email Page 4 Bank Day email Page 5 Event info email Page 6 Thank-you email, goal met Page 7 Thank-you email, goal not met Page 8 CEO Voicemail messages Page 9 CEO Letter to recruit co-captains Page 10 CEO Challenge letter Page 11 CEO Vendor letter 1 Recruitment email Subject: Walking together for stronger, healthier babies It’s March for Babies® season, and [COMPANY] would like you to join our team in support of the March of Dimes. Need a reason to walk with us? How about nearly half a million reasons: that’s how many babies are born too soon every year in the United States — [NUMBER FROM peristats.org] of them right here in [STATE]. With you on our team, we can give families hope by raising money to fund lifesaving research and programs that help moms and babies. Our goal is to raise $[AMOUNT]. To reach that goal, we need at least [20 PERCENT OF STAFF] people to sign up to raise money and walk. Can we count you in? Getting started is easy. Just go to marchforbabies.org/TEAMNAME and click “join this team.” And check out our fundraising here. [NAME] March for Babies Team Captain [EMAIL] P.S. Save the date: our event takes place on [DATE] at [LOCATION]. 2 Fundraising email Subject: March for Babies 2017 — Join us Team, it’s time to kick it into high gear! Walking in March for Babies® is a great way to raise awareness about the hundreds of thousands of babies born prematurely or with birth defects. -

2021 Lent Devotionals

Lent 2021 Lent 2021 Feb. 17 Passing a Hearing Test 6 Ash Wednesday Dr. Rich Menninger, retired Andrew B. Martin Professor of Religion Feb. 18 Love: a Lenten Challenge 7 Fredrikson Center Team Feb. 19 Prioritizing our Preparation 8 Pastor Jason Foulkerts Feb. 20 Beauty is Only Skin Deep 9 Dr. Rich Menninger, retired Andrew B. Martin Professor of Religion Feb. 22 Fall 10 Fredrikson Center Team Feb. 23 Walking in the Faith 11 Sydney Shrimpton Feb. 24 Worst-Case Scenario 12 Dr. Rich Menninger, retired Andrew B. Martin Professor of Religion Feb. 25 Plans 13 Nicole Hamilton Feb. 26 Gratefulness has an ability to Prevent Discouragement over Our Sins and Weaknesses 14 Rev. Justin Gnanamuthu, C.S.C. Feb. 27 Who’s Pulling the Strings? 15 Dr. Rich Menninger, retired Andrew B. Martin Professor of Religion Mar. 1 On High 16 Fredrikson Center Team Mar. 2 Everyone Gets in Trouble 17 Fredrikson Center Team Mar. 3 That Should Have Been Me! 18 Dr. Rich Menninger, retired Andrew B. Martin Professor of Religion Mar. 4 God’s Providence 19 Sydney Shrimpton Mar. 5 The Secret-Sauce for Impossible Victory 20 David J. Grummon Mar. 6 The Grass Isn’t Always Greener 21 Dr. Rich Menninger, retired Andrew B. Martin Professor of Religion Mar. 8 Held Within Protection 22 Fredrikson Center Team Mar. 9 Lenten Prayer 23 Mary Alice Grosser Mar. 10 When God’s in Charge 24 Dr. Rich Menninger, retired Andrew B. Martin Professor of Religion Mar. 11 God’s Ways are Higher than Our Ways 25 Janice Trigg Mar. -

Novena Prayer Group Weekly Individual and Small Group Opportunity

Novena Prayer Group Weekly Individual and Small Group Opportunity Friday, July 31st Greetings Health and Transition Services and Community Residential Program Associates. I hope this message finds you well. We are writing with today’s weekly Novena Prayer program July 31st, 2020. Once again here’s what you need to participate; A Smart TV, a phone, tablet or computer with YouTube access A calm, connected presence to share 30 minutes A quiet space The following pages contain all you need to proceed. The link to YouTube songs are included. Simply enjoy reading the reflections & Gospel while pausing to watch and listen to the music where noted. In between readings and songs, people can pause for a moment of reflection and conversation with one another. Your weekly comments and suggestions are always appreciated. Please send them to us at [email protected] or [email protected] Take a calm, full breath, slowly relax as you breathe out, and begin… Kind regards, Andrew Terhoch, Spiritual Health Practitioner Wilson Cortes, Spiritual Health Associate This document is available in alternative formats. For assistance please contact (204) 256-4301. Page | 1 Friday, July 31, 2020 (If you wish to use a Smart TV or tablet to view the songs, Enter the following URL in the browser app bit.ly/STAnovena) Welcome to everyone to this week’s Friday Novena Prayer Group. We will begin with an opening song titled “We Remember” By Marty Haugen https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bFZ1NiXzJew Reading a Gospel is a lesson of peace, love, compassion, truth, understanding, and positive activism. -

Service of Worship

SERVICE OF WORSHIP SUNDAY, JANUARY 1, 2017 EPIPHANY SUNDAY GOD’S VISION FOR US To be a community of faith Inviting all to encounter Jesus, Preparing believers to deepen their dependence on God, Caring for those who are hurting, Sending ordinary people into the world equipped to do extraordinary things. 3 WELCOME TO EDENTON STREET We hope that all who pass through our doors will sense the love of Christ! It is in community with others that we grow in faith and serve the world. You are invited to learn more about this congregation and how we are in ministry to the world and one another by contacting Joy Owen, Director of Welcoming Ministries. Interested in becoming a member of Edenton Street? Contact Joy for more information at [email protected]. PRAYER AND CARE Fill out a prayer request card in the pews or email [email protected]. We also have trained Care Ministers to talk and pray with you, email [email protected]. 4 PASTORS ROBERT J. “BOB” BAUMAN Senior Pastor LISA N. YEBUAH Pastor, Southeast Raleigh Campus JUSTIN A. MORGAN Pastor, Church on Morgan WILLIAM S. “WILL” HASLEY Pastor of Discipleship Ministries WILLIAM M. “WILL” MCLEANE Pastor, Original Campus MUSICIANS JOSHUA D. DUMBLETON Organist & Associate Director of Music ELLEN KAEHLER Choir Director GABRIEL RAMOS Cellist CHANCEL CHOIR 5 LITURGY GUIDE Bold Black Text - SPOKEN BY CONGREGATION Black Text - SPOKEN BY LEADER + CROSS INDICATES WHEN TO STAND, IF ABLE UMH # - PAGE NUMBER OF THE HYMNAL FOUND IN PEWS HEARING AIDS AND LARGE PRINT HYMNALS These are available from the ushers. -

“A Call to Arms” Sermon for the First Sunday After Pentecost N. Farnham & St

“A Call to Arms” Sermon for the First Sunday after Pentecost N. Farnham & St. John’s Episcopal Churches June 7, 2020 – The Rev. Torrence Harman The Church calls today Trinity Sunday. Given our passages appointed for today it feels more like “Farewell Sunday.” And in a way it truly is as we cross over into Ordinary Time – the longest period in our liturgical year – with Paul and Jesus taking leave of their “congregations.” Two thousand years later we are crossing over into a time that definitely is not “ordinary.” And we do so as the heat of summer and the heated emotions all around envelop us. In our passages today we have good-bye speeches by Paul and Jesus – both of whom well knew traumatic times. They are taking their leave of us just when it seems we really need them to stay around, walk with us, talk us through the societal traumas our times are presenting. What do they have to say? Listen to Paul’s final words in the final passage of his Second Letter to the Corinthians. Finally, brothers and sisters, farewell. Put things in order, listen to my appeal, agree with one another, live in peace and the God of love and peace be with you. Greet one another with a holy kiss. All the saints greet you. The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ, the love of God and the communion of the Holy Spirit be with all of you. Now listen to the final passage of the final chapter of Matthew’s Gospel offering Jesus’ final words to his disciples as he “ascends” back from where he came. -

Lenten Journey, We Want to Spend Time Reflecting on the Scripture and in Prayer

LENT, A JOURNEY TO DICIPLESHIP A PERIOD FOR PURIFICATION AND ENLIGHTENMENT A PERSONAL WALK ON THE ROAD TO EMMAUS Jesus himself drew near and walked with them on the road to Emmaus. The unknown stranger spoke and their hearts burned. Walk with us too! Let our hearts burn within us! Their eyes were opened when he blessed and broke bread. Let us know you in the breaking of the bread, and in every person we meet. They begged him to stay with them in the village they called home. Please stay with us. Do not leave us at the end of this day, or at the end of all of our days. #1214167v1 1858-26 1 INTRODUCTION1: Each year, Lent offers us a providential opportunity to deepen the meaning and value of our Christian lives, and it stimulates us to rediscover the mercy of God so that we, in turn, become more merciful toward our brothers and sisters. In the Lenten period, the Church makes it her duty to propose some specific tasks that accompany the faithful concretely in this process of interior renewal: these are prayer, fasting and almsgiving. In this year’s Lenten journey, we want to spend time reflecting on the Scripture and in prayer. We are not unlike the disciples who were accompanied by the Lord on the road to Emmaus. They reflected on the Scripture as Jesus explained it to them. And they engaged in the most formidable type of prayer known to us, a dialogue with the Risen Lord. The materials that follow are presented to you as “signposts” on your personal walk with Jesus this Lent. -

Walk Withwaterford, Virginia Us…

Walk withWaterford, Virginiaus… A National Historic Landmark WELCOME TO WATERFORD The story of Waterford is the story of the diverse In 1970 the Secretary of the Interior designated Waterford and enterprising people and its rural surround a National Historic Landmark. who have lived and Preserving the village and its setting as a national site labored and built here for everyone is the principal business of the nonprofit from the 1730s to the Waterford Foundation, which has prepared this guide. present. Take time to Waterford began in 1733 around Janney’s Mill, at the explore the results of all lower end of Main Street. The tiny settlement soon their work; the pace of expanded southeast along that street and—shortly after life in the village is slow, 1800—up Main Street Hill. Then, as additional land even now. became available for development in 1812, building lots were laid out down Second and High Streets. On your tour you will see houses from the mid 18th century to the 21st. Where known, their dates of construction are noted in the text. A more detailed overview of Waterford’s past follows for those interested in the historical context of the buildings you see around you. We hope you enjoy your tour. During your visit, please respect personal property and privacy—Waterford is a living town. If you wish further information about the village or events, rentals, guided walking tours, or membership, contact the Foundation office in the Old School, at 40222 Fairfax Street, 9am-5pm Tuesday-Friday. You may reach us by telephone at 540-882-3018, by fax 540-882-3921 or visit our website at www.waterfordfoundation.org. -

Great Thanksgiving

Great Thanksgiving HYMN #617: I Come with Joy One: The Lord be with you. Many: And also with you. Lift up your hearts. We lift them up to the Lord. Let us give thanks to the Lord our God. It is right to give our thanks and praise. O God, you created the universe with a shout of joy, a word of delight and a big bang. You made gravity holes and antimatter, swirling electrons and dancing quarks, shooting stars and sapphire blue planets. You filled the ocean with clown fish and sharks, with dolphins and killer whales. You filled the air with doves and hawks, songbirds and hummingbirds. You covered the land with shimmering aspen and weathered pine. And You blessed all the creatures of the earth: the bugs, snakes, lizards, the lions, tigers, and bears, the puppies and the hippos, the zebras and the penguins. And You blessed all the children of the earth every shape and size, every color and complexion, every makeup and mood, every style and substance. But we, O God, preferred to go our own way. We messed things up. We wanted to be in charge. We wanted to be in control. We thought everything belonged to us. We polluted the environment. We destroyed each other. We turned playgrounds into battlefields, schoolyards into mine fields, hospitals into death camps, and children into killers. But God, you never gave up on us. You never walked away or walked out. You always honored your promises even when we broke ours. You always welcomed us home with open arms and a warm heart Even when our fists were clenched and our minds still closed. -

Welcome Packet

Welcome Packet Welcome Virtual Walker! What Is The Virtual Walk? The Virtual LUNG FORCE Walk will allow us to continue creating awareness and funding for lung cancer, COPD, COVID-19, asthma while practicing social distancing to keep everyone safe. It will begin with the August 22nd Virtual KickOff Ceremony to learn more about our virtual event and how the money raised will be used. At that time, we will also introduce our virtual challenges and a chance to earn prizes. Each participant must register so please do so today! On September 26th, we will gather for our Virtual Day of Ceremony. We’ll be inspired to hear from our Lung Heroes, remember those who have lost their breath, sponsor welcome, watch a video montage of your challenge submissions, announce winners of our challenges and fundraising while awarding runner/walker participation using the Strava App. Then we’ll walk in our neighborhood, park or other venue to raise awareness and show our FORCE! Why Do We Walk? • Lung cancer is the #1 cancer killer of women and men. • More than 36 million Americans are currently living with a chronic lung disease. • COVID-19 is a respiratory virus that attacks the lungs and can be fatal, regardless of age. What Should I do Next? • Join our Virtual LUNG FORCE Walk New Jersey Facebook Group for the most up to date information and to interact with other Virtual Walk participants. • Download Strava and join the LUNG FORCE Walk Bridgewater Club. Track your miles whenever you exercise. The top three distance finishers will be announced at the Opening Ceremony and receive LUNG FORCE swag. -

Kris Uppendahl

God’s Story By Kris Uppendahl God’s story of salvation for humankind is the to come and break their chains. The chains of overarching theme throughout scripture from slavery. The chains of hopelessness. The chains of Genesis to Revelation. Kris Uppendahl, one of our exhaustion. Here was a people needing to be set Financial Aid Counselors here at LAPU, has offered free. the following thoughts to help us conceptualize how our lives in this season of advent connect to God’s THEN, THE SAVIOUR CAME. story of salvation. But what does that mean? Truly, how do we begin to grasp the concept of God coming into our world GOD WITH US and our chaotic mess in order to walk with us—that “O Come, O Come, Emmanuel, and ransom captive God would give up some of His glory for a time, Israel. That mourns in lonely exile here, until the Son in order to be among those who are fallen and far of God appears. ” (Neal, 1851) from having it all together? Yet, that is exactly what our God did. Through the Incarnation, God became O Come, O Come, Emmanuel. With the birth of flesh, He came to us. Not expecting us to rise to Christ, God came to us indeed, fulfilling the groans Him, for truly how could we? Rather, Emmanuel, of humanity and setting in motion His plan of God with us, wanted more. redemption. A new chapter in the overarching story of God’s salvation for us was begun, and the world He wanted to be in our lives.