Professional Liability Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

H 5766 State of Rhode Island

2021 -- H 5766 ======== LC000028 ======== STATE OF RHODE ISLAND IN GENERAL ASSEMBLY JANUARY SESSION, A.D. 2021 ____________ A N A C T RELATING TO BUSINESSES AND PROFESSIONS -- ARCHITECTS Introduced By: Representatives Williams, Hull, Barros, Alzate, Batista, Henries, Biah, Morales, Giraldo, and Perez Date Introduced: February 24, 2021 Referred To: House Corporations It is enacted by the General Assembly as follows: 1 SECTION 1. Section 5-1-7 of the General Laws in Chapter 5-1 entitled "Architects" is 2 hereby amended to read as follows: 3 5-1-7. Practice prohibited -- Criminal penalties -- Injunctions. 4 (a) No individual shall: 5 (1) Practice or offer to practice architecture in this state; 6 (2) Use any title, sign, card, or device implying that the individual is an architect or is 7 competent to practice architecture in this state; 8 (3) Use in connection with his or her name, or otherwise, any title or description conveying 9 or tending to convey the impression that the individual is an architect or is competent to practice 10 architecture in this state; or 11 (4) Use or display any words, letters, figures, seals, or advertisements indicating or 12 implying that the individual is an architect or is competent to practice architecture in this state, 13 unless that individual holds a currently valid certificate of registration/authorization issued pursuant 14 to this chapter or is specifically exempted from holding a certificate under the provisions of this 15 chapter. 16 (b) No sole proprietorship, partnership, limited-liability partnership, -

CVG-Firm-Profile-2020.Pdf

CCHARRETTVE VENTUGRE GROUP Your architecture firm is unique. Your challenges aren't. We invest in small to mid-sized architecture firms. WWW.CHARRETTEVG.COM | (515)-207-2422 CVGCHARRETTE VENTURE GROUP Filling the void. Charrette Venture Group is one of the world’s only investment companies focusing on growing small-to-mid-sized architecture firms. Our mission is to help architecture firms become better businesses. We offer a unique, shared-risk partnership model that provides financial management, leadership development, marketing and business development, organizational design, ownership transition advisory services, recruitment, and other critical business infrastructure in exchange for a percentage of net operating revenue for a five-year period. If you don’t succeed, we don’t succeed. No equity stake is transferred. There are other companies who do management consulting, but CVG goes beyond that—we are focused on being a long-term partner who takes a stake in both the risk and the reward of our partners’ success. We have architectural roots with an entrepreneurial drive. Our founder, Matt Ostanik, AIA, founded two successful technology companies born from his experience working in architectural firms. He observed architects struggling with business priorities, noticing that they might be excellent at design, but have difficulty dedicating time to marketing, business development, and staff nurturing. When our clients want to strengthen their business acumen, CVG executes a plan for change and growth. Our impact is not only on the firm and its financial picture; but also on the lives of firm owners and employees. How we work with you. Each relationship begins with a holistic assessment report where we review your financial metrics, marketing and business development efforts, operations, and culture. -

THE NORTH CAROLINA BOARD of ARCHITECTURE 21St Combined Edition (11/01/2017)

THE NORTH CAROLINA BOARD OF ARCHITECTURE 21st Combined Edition (11/01/2017) Architectural Practice Act Rules of the State Board 127 West Hargett Street Suite 304 Raleigh, NC 27601 (919) 733-9544 [email protected] www.ncbarch.org Members As of November 2017 Robert W. Bishop, AIA, Vice President Steven G. Clipp, AIA, Treasurer Fred Dodson, Jr – Public Member Stephen M. McClure, Public Member, President Jimmy L. Norwood, Jr. AIA, Secretary Katherine N. Peele, FAIA, Member John H. Tabor, FAIA, Member Board of Architecture Staff Cathe M. Evans Executive Director Julie L. Piatek Director of Administration Tyler D. Barrick Firm/CE Compliance Administrator 1 | Page PAGE Law - General Statute 83A. Architects 3 Rules - North Carolina Administrative Code 9 Title 21 Chapter 2 Architecture Other Relative Statutes 33 General Statute 55B – The Professional Corporation Act General Statute 57C – The Professional Limited Liability Statute General Statute 59 - Partnerships Article 3D. Procurement of Architectural, Engineering, and Surveying Services. § 143-64.31. Declaration of public policy. (“Mini-Brooks Act or “Fee Bidding”) 2 | Page Chapter 83A. Architects. § 83A-1. Definitions. When used in this Chapter, unless the context otherwise requires: (1) "Architect" means a person who is duly licensed to practice architecture. (2) "Board" means the North Carolina Board of Architecture. (3) "Corporate certificate" means a certificate of corporate registration issued by the Board recognizing the corporation named in the certificate as meeting the requirements for the corporate practice of architecture. (4) "Corporate practice of architecture" means "practice" as defined in G.S. 83A-1(7) by a corporation which is organized or domesticated in this State, and which holds a current "corporate certificate" from this Board. -

Architectural Firm Case Study

CREATING AN UNEXPECTED PATH TO PROFITABLE REVENUE CLIENT INDUSTRY: ARCHITECTURAL FIRM Architectural firm focused on zoos & aquariums, higher education, healthcare and government. CLIENT GOALS: CREATE DESIGN WORK BY IDENTIFYING FUNDING FOR PROJECTS While this firm has a strong reputation and market experience, it would frequently run into the same issue over and over. Their clients would say, “We are in love with your design and plans, but just don’t have the funding for this project.” OUR DELIVERY PATH Work Creation via Partner Collaboration We helped our client create a strategic partnership with a third party service provider, who happened to be another client of ours. When working together, the two companies could ultimately help project owners free up operational budget – by leveraging an energy performance contract from the service provider -- that would help them pay for a new architectural project – with design from the architectural firm. We like to call this a “Stewardship to Equity” strategy. What is "Stewardship to Equity" Let's break it down. "Stewardship" means responsible overseeing and protection of something considered worth caring for and preserving. So, you need to behaviorally demonstrate financial diligence with your own assets. "Equity" essentially translates to the value or worth you create. So by exhibiting proper “stewardship” over your assets (i.e. leveraging an energy performance contract), you can create “equity” that can be invested into capital projects (i.e. design of a new facility). Architectural Firm Wayne O’Neill & Associates Case Study Page 1 Opportunity Facilitation via the “Meeting Behind the Meeting” We facilitated a meeting behind the meeting during a large industry association convention that enabled our client to present their new value creation model to 10-15 decision makers in their target audience. -

ARCHITECTS LICENSURE LAW - OMNIBUS AMENDMENTS Act of Feb

ARCHITECTS LICENSURE LAW - OMNIBUS AMENDMENTS Act of Feb. 18, 1998, P.L. 186, No. 31 Cl. 63 Session of 1998 No. 1998-31 HB 1291 AN ACT Amending the act of December 14, 1982 (P.L.1227, No.281), entitled "An act regulating the practice of architecture in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania; providing for the examination and licensure of architects by a State Architects Licensure Board; and providing penalties," adding definitions; further providing for firm practice, for permitted practices and for unauthorized practice; and making editorial changes. The General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania hereby enacts as follows: Section 1. Section 3 of the act of December 14, 1982 (P.L.1227, No.281), known as the Architects Licensure Law, is amended by adding definitions to read: Section 3. Definitions. The following words and phrases when used in this act shall have, unless the context clearly indicates otherwise, the meanings given to them in this section: * * * "Design-build." A project delivery method whereby a design-build entity signs a single contract to provide a combination of architectural and construction services to a client. "Design-build entity." An entity which provides by single contract to a client a combination of architectural and construction services. * * * Section 2. Sections 13, 15 and 18(b) of the act are amended to read: Section 13. Firm practice. (a) An individual architect or a group of architects in Pennsylvania may practice architecture in one of the following forms of architectural firms: (1) sole proprietorship; (2) partnership; (3) professional association; (4) professional corporation; [or] (5) business corporation[.]; (6) limited liability company; or (7) limited liability partnership. -

Architectural Firm, Organizational Structure, External Environment, Performance

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Covenant University Repository International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 2014, 3(1): 1-12 DOI: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20140301.01 Organizational Structure of Architectural Firms and Their Performances Adedapo Adewunmi Oluwatayo1,*, Dolapo Amole2 1Department of Architecture, Covenant University, Ota, Ogun State, 110001, Nigeria 2Department of Architecture, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Osun State, 220282, Nigeria Abstract The focus of this study is the organizational structure of architectural firms where the mode of coordination had been unclear. The types of organizational structure in architectural firms were identified using data obtained from 92 architectural firms in Nigeria. The findings show that sizes of the firms was an important factor, which influenced the organizational structures adopted by the architectural firms. Although, sizes of the firms also had direct influence on the performance, no interaction of this variable or any internal firm characteristic with organizational structure led to any significant change in performance. Although the environment did not directly influence organizational structure, it appeared that particular organizational structures worked best when some external influences are high and resulted in higher profit. The results show that while adhoc structure leads to better performance in firms where the influence of other professionals is considered high, the administered structure is more effective highly influenced by government privatization programmes. Only the adhoc structure was however not suitable for firms strongly influenced by increasing concerns for sustainable environment. The results of the study suggest that while larger architectural firms may record higher profit, architectural firms that adapt their organizational structures to environmental conditions to reap improved profit. -

Architectural Firm Initial Registration Application Instructions

Architectural Firm Initial Registration Application Instructions All firms practicing architecture in Louisiana are required to register with the LSBAE and receive a Certificate of Authority within thirty days following registration with the Secretary of State. The legislature has enacted laws which govern all firms practicing architecture in Louisiana. In accordance with those laws, the LSBAE has adopted rules which regulate the registration of such firms. Types of firms that may qualify for registration as an Architectural Firm include corporations, partnerships, limited liability partnerships, limited liability companies, associations, sole proprietorships, or other entities lawfully organized under the laws of Louisiana or other lawful jurisdiction for the purpose of practicing architecture. An Architectural Firm will be required to designate one or more supervising professional architects who shall perform or directly supervise the performance of all architectural services by the firm in Louisiana. See Board Rule §1705.G. Depending on the structure of the firm, you may be required to designate an in-state registered agent with the Louisiana Secretary of State, and other general corporation laws may be applicable. There are no shareholder or control requirements to register as an Architectural Firm. If your firm has been previously registered and you already have a license beginning in “LL,” “AC,” or “AE,” please list your current firm license number. Approval of an Architectural Firm registration will automatically render your previous registration inactive. Do not use this form unless you are applying for an Architectural Firm registration. Please make sure we have an email contact for your firm. 1. Please provide your business name. -

Business Plan BETA TEMPLATE for SMALL ARCHITECTURE FIRMS

Business Plan BETA TEMPLATE FOR SMALL ARCHITECTURE FIRMS Small Firm Exchange ______________________________________ an AIA Member Group Advancing the mutual interests of architects practicing in small firms. Help us improve our tools and resources. Submit your comments and questions about the SFx Business Plan Beta-Template to [email protected] 1 Introduction from Small Firm Exchange (SFx) SFx doesn’t just support small firms. We are small firms. The Small Firm Exchange (SFx) is a group of small firm practitioners who represent the needs of small architecture firms to AIA National. We also provide essential practice and leadership resources, an expansive professional network, and advocacy to small firms everywhere. Learn more and find your rep at aia.org/SFx. Small Firm Business Model Data SFx has been exploring the question of which business models are most appropriate to sustain the practice of architecture for small firms. The survey data we’ve collected represents only a fraction of the results coming out of this focus. Continued efforts promise more detailed information, case studies, and recommendations to follow in the coming year. History: The AIA had been wrestling with the definition of a small firm for many years, and in 2005 assembled a Special Task Force assigned with defining a small firm, and how many staff are required to be considered mid-sized or large. For sole practitioners, the definition was obvious. Single person firms can be defined as small. Also, for organizations with 100 or more staff, it seemed clear that these could be defined as large. But what to label all of those firms with staff between two and 99. -

Application of Indiana's Architect Licensing Laws To

Application of Indiana’s Architect Licensing Laws to Businesses Engaged in Architecture Prepared for AIA Indiana by: William E. Kelley, Jr. 1. Individuals may be registered or licensed in the State of Indiana as architects. Firms or businesses are not registered or licensed in the State of Indiana as architects. a. See Indiana Code (“I.C.”) 25-4-1-6(a) (“A person desiring to engage in the practice of architecture: (1) shall apply to the board for a certificate of registration in compliance with this chapter; (2) shall submit evidence to the board that the person is qualified to engage in the practice of architecture in compliance with the requirements of this chapter, including evidence that the person: (A) graduated with a professional degree from a school or college of architecture accredited by the National Architectural Accrediting Board, Inc., or its successor; (B) successfully completed the required examination; and (C) successfully completed the intern development program required under section 7.5 of this chapter; and (3) must not have been convicted of: (A) an act that would constitute a ground for disciplinary sanction under IC 25-1-11; or (B) a felony that has direct bearing on the applicant’s ability to practice competently.”). b. See also See 804 IAC 1.1-1-1(21): “Registrant” means a registered architect or landscape architect, unless the context clearly indicates otherwise, whose qualifications have been examined by the board and a certificate of registration granted. 2. An architectural firm may, but is not required, to incorporate as a professional corporation. All rights reserved. -

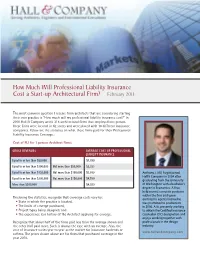

2011 First Time Buyer Copy

How Much Will Professional Liability Insurance Cost a Start-up Architectural Firm? February 2011 The most common question I receive from architects that are considering starting their own practice is “How much will my professional liability insurance cost?” In 2010 Hall & Company wrote 315 architectural firms that employed one person. These firms were located in 42 states and were placed with 10 different insurance companies. Below are the statistics on what these firms paid for their Professional Liability Insurance Coverage.: Cost of PLI for 1 person Architect Firms GROSS REVENUES AVERAGE COST OF PROFESSIONAL LIABILITY INSURANCE Equal to or less than $50,000 $1,780 Equal to or less than $100,000 But more than $50,000 $2,353 Equal to or less than $150,000 But more than $100,000 $3,689 Anthony J. (AJ) Fugitt joined Hall & Company in 2004 after Equal to or less than $200,000 But more than $150,000 $4,780 graduating from the University More than $200,000 $4,929 of Washington with a bachelor’s degree in Economics. AJ has held several associate positions within the firm and upon This being the statistics, recognize that coverage costs vary by: earning his agents license he • State in which the practice is located, was promoted to production • The limits of coverge purchased, in 2006. AJ is presently working • Project types being designed, and to obtain the Certified Insurance • The experience loss history of the Architect applying for coverge. Counselor (CIC) designation and enjoys working together with Recognize that about half of the firms paid less than the average shown and professionals in the design the other half paid more. -

Construction Design Professional Insurance and Indemnity

Presenting a live 90-minute webinar with interactive Q&A Construction Design Professional Insurance and Indemnity: Reconciling Coverage With Contractual Risks Assessing Indemnification, Additional Insured and Other Service Provider Agreement Terms to Ensure Adequate Coverage TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 4, 2014 1pm Eastern | 12pm Central | 11am Mountain | 10am Pacific Today’s faculty features: John D. Broghammer, Partner, Greve Clifford Wengel & Paras, Sacramento, Calif. William E. Kelley, Attorney, Drewry Simmons Vornehm, Carmel, Ind. The audio portion of the conference may be accessed via the telephone or by using your computer's speakers. Please refer to the instructions emailed to registrants for additional information. If you have any questions, please contact Customer Service at 1-800-926-7926 ext. 10. FOR LIVE EVENT ONLY Sound Quality If you are listening via your computer speakers, please note that the quality of your sound will vary depending on the speed and quality of your internet connection. If the sound quality is not satisfactory, you may listen via the phone: dial 1-866-871-8924 and enter your PIN when prompted. Otherwise, please send us a chat or e-mail [email protected] immediately so we can address the problem. If you dialed in and have any difficulties during the call, press *0 for assistance. Viewing Quality To maximize your screen, press the F11 key on your keyboard. To exit full screen, press the F11 key again. FOR LIVE EVENT ONLY For CLE purposes, please let us know how many people are listening at your location by completing each of the following steps: • In the chat box, type (1) your company name and (2) the number of attendees at your location • Click the SEND button beside the box If you have purchased Strafford CLE processing services, you must confirm your participation by completing and submitting an Official Record of Attendance (CLE Form). -

North Carolina Board of Architecture

CHAPTER 2 - BOARD OF ARCHITECTURE SECTION .0100 - GENERAL PROVISIONS 21 NCAC 02 .0101 AUTHORITY: NAME AND LOCATION OF BOARD The "North Carolina Board of Architecture," subsequently herein referred to as the "Board," is established and authorized by Chapter 83A of the General Statutes of North Carolina. Unless otherwise directed, all communications shall be addressed to the Board at 127 West Hargett Street, Suite 304, Raleigh, North Carolina 27601. History Note: Authority G.S. 83A-2; 83A-6; Eff. February 1, 1976; Readopted Eff. September 29, 1977; Amended Eff. June 1, 1995; May 1, 1989; November 1, 1979; Pursuant to G.S. 150B-21.3A, rule is necessary without substantive public interest Eff. January 13, 2015. 21 NCAC 02 .0102 ORGANIZATION OF BOARD AND OFFICERS In addition to the annual meeting as prescribed in G.S. 83A-2, other meetings of the Board may be called by the president or any three Board members. The officers of the Board shall be elected at the annual meeting for terms of one year and until a successor is elected. Vacancies in the officers' terms, occurring from death, resignation, disability or expiration of Board service, shall be filled by election at the next Board meeting following the vacancy. History Note: Authority G.S. 83A-2; 83A-6; Eff. February 1, 1976; Readopted Eff. September 29, 1977; Amended Eff. May 1, 1989; November 1, 1979; Pursuant to G.S. 150B-21.3A, rule is necessary without substantive public interest Eff. January 13, 2015. 21 NCAC 02 .0103 DUTIES OF OFFICERS 21 NCAC 02 .0104 PROCEDURE 21 NCAC 02 .0105 DISCIPLINARY ACTION AND PROCEDURE History Note: Authority G.S.