Barrier-Breaking Bengals Coach Still Making a Difference in Retirement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Futebol Americano © Paulo Mancha

Paulo Mancha 100 histórias divertidas, curiosas e inusitadas do futebol americano © Paulo Mancha Diretor editorial Projeto gráfico e diagramação Marcelo Duarte Carolina Ferreira Diretora comercial Capa Patty Pachas Mario Kanegae Diretora de projetos especiais Preparação Tatiana Fulas Beatriz de Freitas Moreira Coordenadora editorial Revisão Vanessa Sayuri Sawada Juliana de Araujo Rodrigues Assistentes editoriais Impressão Juliana Silva Corprint Mayara dos Santos Freitas Assistentes de arte Carolina Ferreira Mario Kanegae CIP – BRASIL. CATALOGAÇÃO NA FONTE SINDICATO NACIONAL DOS EDITORES DE LIVROS, RJ Mancha, Paulo Touchdown! 100 histórias divertidas, curiosas e inusitadas do futebol americano/ Paulo Mancha. – 1. ed.– São Paulo: Panda Books, 2015. 168 pp. ISBN: 978-85-7888-502-1 1. Futebol - Competições - História. I. Título. CDD: 796.334 15-22157 CDU: 796.332 2015 Todos os direitos reservados à Panda Books. Um selo da Editora Original Ltda. Rua Henrique Schaumann, 286, cj. 41 05413-010 – São Paulo – SP Tel./Fax: (11) 3088-8444 [email protected] www.pandabooks.com.br twitter.com/pandabooks Visite também nossa página no Facebook. Nenhuma parte desta publicação poderá ser reproduzida por qualquer meio ou forma sem a prévia autorização da Editora Original Ltda. A violação dos direitos autorais é crime estabelecido na Lei n 9.610/98 e punido pelo artigo 184 do Código Penal. Este livro é dedicado à família D’Amaro e à minha amada Elena Vorontsova. Eles têm sido minha linha ofensiva, meus running backs e meus wide receivers nesta jornada. Sumário Apresentação .............................................................................13 1. Por que se chama futebol se é jogado com as mãos? ................17 2. Quando o touchdown não valia pontos ...................................18 3. -

Touchdown!: Achieving Your Greatness on the Playing Field Of

Praise for Touchdown! “Just as one individual makes a diff erence, so can one book make a diff erence. If you follow what it teaches, you will be in a much higher place and get what you deserve, which is victory.” Butch Davis, former Head Coach of the NCAA Champion University of Miami and current Head Coach of the University of North Carolina “Kevin Elko played a huge part of putt ing Rutgers Football on the map. We use what he has taught us every day in our coaching. We owe him for teaching us ‘Th e Chop.’” Greg Schiano, Head Coach, Rutgers University Football “Dr. Elko taught me ‘You have to dream it to achieve it’ and that before championships and pro bowls happen, they have already occurred in your mind. From the moment I learned it I have not only played that way, I have led that way.” Ed Reed, All Pro Safety, Baltimore Ravens “Over my career at the University of Miami, I learned a lot of lessons from Kevin that helped lift myself and my teammates to a higher level. His creativity with his teachings, and the fact that what he taught us worked, was a major reason I still believe in what he taught me to this day.” Ken Dorsey, Quarterback, Cleveland Browns, and former Quarterback of 2001 University of Miami National Champions “Over the course of my career, the principles that Dr. Elko taught were instrumental in me being a starter in the NFL. Th ese principles are now still what I teach to my athletes in the weight room.” Tom Myslinski, MS, CSCS, Head Strength & Conditioning Coach, the Cleveland Browns Football Club “If I had one choice for someone to work with my fi rm, I would pick Kevin Elko. -

INDIANAPOLIS COLTS WEEKLY PRESS RELEASE Indiana Farm Bureau Football Center P.O

INDIANAPOLIS COLTS WEEKLY PRESS RELEASE Indiana Farm Bureau Football Center P.O. Box 535000 Indianapolis, IN 46253 www.colts.com REGULAR SEASON WEEK 6 INDIANAPOLIS COLTS (3-2) VS. NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (4-0) 8:30 P.M. EDT | SUNDAY, OCT. 18, 2015 | LUCAS OIL STADIUM COLTS HOST DEFENDING SUPER BOWL BROADCAST INFORMATION CHAMPION NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS TV coverage: NBC The Indianapolis Colts will host the New England Play-by-Play: Al Michaels Patriots on Sunday Night Football on NBC. Color Analyst: Cris Collinsworth Game time is set for 8:30 p.m. at Lucas Oil Sta- dium. Sideline: Michele Tafoya Radio coverage: WFNI & WLHK The matchup will mark the 75th all-time meeting between the teams in the regular season, with Play-by-Play: Bob Lamey the Patriots holding a 46-28 advantage. Color Analyst: Jim Sorgi Sideline: Matt Taylor Last week, the Colts defeated the Texans, 27- 20, on Thursday Night Football in Houston. The Radio coverage: Westwood One Sports victory gave the Colts their 16th consecutive win Colts Wide Receiver within the AFC South Division, which set a new Play-by-Play: Kevin Kugler Andre Johnson NFL record and is currently the longest active Color Analyst: James Lofton streak in the league. Quarterback Matt Hasselbeck started for the second consecutive INDIANAPOLIS COLTS 2015 SCHEDULE week and completed 18-of-29 passes for 213 yards and two touch- downs. Indianapolis got off to a quick 13-0 lead after kicker Adam PRESEASON (1-3) Vinatieri connected on two field goals and wide receiver Andre John- Day Date Opponent TV Time/Result son caught a touchdown. -

LMR 03 - Week 19 Destiny's Nephew

LMR 03 - Week 19 Destiny's Nephew If you didn't enjoy last week's Division Playoffs, you don't have a pulse. The action was so intense that it reminded the Look Man of, well, it was like no other week in NFL Playoff history. Sure there have been some great single games in the playoffs. Games like The Drive, The Fumble, The Catch, The Tuck, The Sea of Hands, the Immaculate Reception, Air Coryell vs. the Killer Bees, and The Freezer Bowl have captured our imagination. But never in the Look Man's memory, has every single Divisional Playoff game come down to a single possession to determine the outcome. Here are but a few of the Greatest Games in NFL playoff history: • 1972 NFC semis: Cowboys 30, 49ers 28 ... Staubach led 17-point 4th quarter at Candlestick vs. John (Jaws) Brodie • 1975 NFC semis: Cowboys 17, Vikings 14 … the first "Hail Mary" - Staubach to Drew Pearson • 1977 AFC semis: Raiders 37, Colts 31 (2 OT) .. The "Ghost to the Post," Stabler to Casper • 1986 AFC semis: Browns 23, Jets 20 (2 OT) … "The Bernie, Bernay Game", Kosar and the Browns score 10 points in the final 4 minutes, and win in OT. Kosar throws 64 times for 489 yards on the day. • 1989 AFC semis: Browns 34, Bills 30 … "Clay Day/Clay Day!" - LB Clay Matthews INT at 1- yard line with 3 seconds left seals it (included a pick by Felix Wright on Don Beebe that was miscalled) • 1998 NFL wild card: 49ers 30, Packers 27 .. -

Furman Vs Clemson (9/10/1988)

Clemson University TigerPrints Football Programs Programs 1988 Furman vs Clemson (9/10/1988) Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms Materials in this collection may be protected by copyright law (Title 17, U.S. code). Use of these materials beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. For additional rights information, please contact Kirstin O'Keefe (kokeefe [at] clemson [dot] edu) For additional information about the collections, please contact the Special Collections and Archives by phone at 864.656.3031 or via email at cuscl [at] clemson [dot] edu Recommended Citation University, Clemson, "Furman vs Clemson (9/10/1988)" (1988). Football Programs. 195. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms/195 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Programs at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Football Programs by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. $2.00 September 10, 1988 Clemson Football *88 i \i\ii<sin Clemson vs. Furman Memorial Stadium Bullish Blockers MANGE YOU WORTHY OF THE BEST? Batson is the exclusive U.S. agent for textile equipment from the leading textile manufacturers worldwide. Experienced people back up our sales with complete service, spare parts, technical assistance, training and follow-up. DREF 3 FRICTION SPINNING MACHINE delivers yarn to 330 ypm. i FEHRER K-21 RANDOM CARDING MACHINE has weight range ^ 2 10-200 g/m , production speedy | m/min. rttfjfm 1 — •• fj := * V' " VAN DE WIELE PLUSH WEAVING MACHINES weave apparel, DORNIER RAPIER WEAVING MACHINES are upholstery, carpet. -

Never Too Late to Graduate

Originally Published: June 2009 $2.00 PERIODICAL NEWSPAPER CLASSIFICATION C DATED MATERIAL PLEASE RUSH!! M Vol. 28, No. 26 “For The Buckeye Fan Who Needs To Know More” June 2009 Y K File Photo File Photo GRADUATION PHOTOS COURTESY OF OSU ATHLETICS & MICHAEL WILEY WE MADE IT! – Former Ohio State women’s basketball star Katie Smith (above left with university president Gordon Gee) and football star Michael Wiley (right) are recent success stories as participants in the Degree Completion Program. Smith, Wiley and many other former OSU athletes have returned under the program to complete their undergraduate studies and receive their degrees. Never Too Late To Graduate Program Gives Buckeyes Chance To Return, Earn Degree As a result, Ohio State has one of the more active By JEFF SVOBODA Degree Completion Programs in college athletics. Buckeye Sports Bulletin Staff Writer In January 2008, Ohio State was honored as one In This Issue Of BSB of the top two universities offering the program for • A profile of former Ohio State receiver For the past 16 years of her life, Katie Smith has the 2006-07 year, and the 2007-08 NCAS honor Thad Jemison, who took advantage of the uni- been a walking ambassador for Ohio State. roll lists Ohio State at the top of the heap among all versity’s Degree Completion Program to earn She burst onto the scene as a freshman in 1993, universities as far as degrees completed. his diploma more than 25 years after his last leading the Buckeye women’s basketball team to Though fellow Big Ten schools Wisconsin and game with the Buckeyes (Page 7) a berth in the national title game. -

Where's My Johnnie Cochran? Tim Paluch Iowa State University

Volume 54 Issue 2 Article 5 December 2002 Where's My Johnnie Cochran? Tim Paluch Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ethos Recommended Citation Paluch, Tim (2002) "Where's My Johnnie Cochran?," Ethos: Vol. 2003 , Article 5. Available at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ethos/vol2003/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ethos by an authorized editor of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ethos I sports Where's My Johnnie Cochran? IT'S HARD FINDING A COACHING JOB WITH A NAME LIKE THIS. column by I TIM PALUCH he NFL just doesn't hire them to be head coaching job, give the job to the white guy, coaches. Jon Gruden isn't one. Well, and still keep all its draft picks. obviously. Mike Martz isn't one. Yeah, Under my plan, at least one Paluch must be a we know that already. Dick Juaron. candidate for the head coaching position. All TDick LeBeau. Bill Cowher. Bill Callahan. other candidates must be named Angelina Jolie. OK, we get it. Jim Haslett. Dave McGinnis. Mike Tice. And, while we wait in the lobby to be inter Mike Holmgren. Enough, you've made your point. viewed, all other candidates can wear nothing There aren't enough black coaches in the NFL. but their resumes. If no Paluchs are inter BLACK coaches? Who said anything about viewed, or if Angelina's resume is longer than black coaches? Those guys have one thing in one page, teams lose a draft pick, must change common, but it's not the color of their skin. -

Miami Dolphins Weekly Release

Miami Dolphins Weekly Release Game 12: Miami Dolphins (4-7) vs. Baltimore Ravens (4-7) Sunday, Dec. 6 • 1 p.m. ET • Sun Life Stadium • Miami Gardens, Fla. RESHAD JONES Tackle total leads all NFL defensive backs and is fourth among all NFL 20 / S 98 defensive players 2 Tied for first in NFL with two interceptions returned for touchdowns Consecutive games with an interception for a touchdown, 2 the only player in team history Only player in the NFL to have at least two interceptions returned 2 for a touchdown and at least two sacks 3 Interceptions, tied for fifth among safeties 7 Passes defensed, tied for sixth-most among NFL safeties JARVIS LANDRY One of two players in NFL to have gained at least 100 yards on rushing (107), 100 receiving (816), kickoff returns (255) and punt returns (252) 14 / WR Catch percentage, fourth-highest among receivers with at least 70 71.7 receptions over the last two years Of two receivers in the NFL to have a special teams touchdown (1 punt return 1 for a touchdown), rushing touchdown (1 rushing touchdown) and a receiving touchdown (4 receiving touchdowns) in 2015 Only player in NFL with a rushing attempt, reception, kickoff return, 1 punt return, a pass completion and a two point conversion in 2015 NDAMUKONG SUH 4 Passes defensed, tied for first among NFL defensive tackles 93 / DT Third-highest rated NFL pass rush interior defensive lineman 91.8 by Pro Football Focus Fourth-highest rated overall NFL interior defensive lineman 92.3 by Pro Football Focus 4 Sacks, tied for sixth among NFL defensive tackles 10 Stuffs, is the most among NFL defensive tackles 4 Pro Bowl selections following the 2010, 2012, 2013 and 2014 seasons TABLE OF CONTENTS GAME INFORMATION 4-5 2015 MIAMI DOLPHINS SEASON SCHEDULE 6-7 MIAMI DOLPHINS 50TH SEASON ALL-TIME TEAM 8-9 2015 NFL RANKINGS 10 2015 DOLPHINS LEADERS AND STATISTICS 11 WHAT TO LOOK FOR IN 2015/WHAT TO LOOK FOR AGAINST THE RAVENS 12 DOLPHINS-RAVENS OFFENSIVE/DEFENSIVE COMPARISON 13 DOLPHINS PLAYERS VS. -

2013 NFL Diversity and Inclusion Report

COACHING MOBILITY VOLUME 1 EXAMINING COACHING MOBILITY TRENDS AND OCCUPATIONAL PATTERNS: Head Coaching Access, Opportunity and the Social Network in Professional and College Sport Principal Investigator and Lead Researcher: Dr. C. Keith Harrison, Associate Professor at University of Central Florida A report presented by the National Football League. DIVERSITY & INCLUSION 1 COACHING MOBILITY Examining Coaching Mobility Trends and Occupational Patterns: Head Coaching Access, Opportunity and the Social Network in Professional and College Sport. Principal Investigator and Lead Researcher: Dr. C. Keith Harrison, Associate Professor at University of Central Florida. A report presented by the NFL © 2013 DIVERSITY & INCLUSION 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PG Message from NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell 5 Message from Robert Gulliver, NFL Executive Vice President 5 for Human Resources and Chief Diversity Officer Message from Troy Vincent, NFL Senior Vice President Player Engagement 5 Message from Dr. C. Keith Harrison, Author of the Report 5 - 6 Background of Report and Executive Summary 7 - 14 Review of Literature • Theory and Practice: The Body of Knowledge on NFL and 1 5 - 16 Collegiate Coaching Mobility Patterns Methodology and Approach • Data Analysis: NFL Context 16 Findings and Results: NFL Coaching Mobility Patterns (1963-2012) 17 Discussion and Conclusions 18 - 20 Recommendations and Implications: Possible Solutions • Sustainability Efforts: Systemic Research and Changing the Diversity and Inclusion Dialogue 21 - 23 Appendix (Data Tables, Figures, Diagrams) 24 References 25 - 26 Quotes from Scholars and Practitioners on the “Good Business” Report 27 - 28 Bios of Research Team 29 - 30 Recommended citation for report: Harrison, C.K. & Associates (2013). Coaching Mobility (Volume I in the Good Business Series). -

Football Bowl Subdivision Records

FOOTBALL BOWL SUBDIVISION RECORDS Individual Records 2 Team Records 24 All-Time Individual Leaders on Offense 35 All-Time Individual Leaders on Defense 63 All-Time Individual Leaders on Special Teams 75 All-Time Team Season Leaders 86 Annual Team Champions 91 Toughest-Schedule Annual Leaders 98 Annual Most-Improved Teams 100 All-Time Won-Loss Records 103 Winningest Teams by Decade 106 National Poll Rankings 111 College Football Playoff 164 Bowl Coalition, Alliance and Bowl Championship Series History 166 Streaks and Rivalries 182 Major-College Statistics Trends 186 FBS Membership Since 1978 195 College Football Rules Changes 196 INDIVIDUAL RECORDS Under a three-division reorganization plan adopted by the special NCAA NCAA DEFENSIVE FOOTBALL STATISTICS COMPILATION Convention of August 1973, teams classified major-college in football on August 1, 1973, were placed in Division I. College-division teams were divided POLICIES into Division II and Division III. At the NCAA Convention of January 1978, All individual defensive statistics reported to the NCAA must be compiled by Division I was divided into Division I-A and Division I-AA for football only (In the press box statistics crew during the game. Defensive numbers compiled 2006, I-A was renamed Football Bowl Subdivision, and I-AA was renamed by the coaching staff or other university/college personnel using game film will Football Championship Subdivision.). not be considered “official” NCAA statistics. Before 2002, postseason games were not included in NCAA final football This policy does not preclude a conference or institution from making after- statistics or records. Beginning with the 2002 season, all postseason games the-game changes to press box numbers. -

Two Records, Different Tunes the RUNDOWN Houston (-3) at Atlanta, 1 P.M

C M Y K D10 DAILY 09-30-07 MD BD D10 CMYK D10 Sunday, September 30, 2007 B x The Washington Post NFLGameday Compiled By Desmond Bieler, Matt Bonesteel, David Larimer and Christian Swezey Two Records, Different Tunes THE RUNDOWN Houston (-3) at Atlanta, 1 p.m. Today, Green Bay’s Brett Favre goes for the all-time NFL mark in touchdown passes. His pursuit of this record comes the same year as The game only a snooty U-Va. fan (is there any Barry Bonds becoming the home-run king. How these players’ quests for statistical immortality stack up against each other: other kind?) could enjoy. The Falcons are reeling Green Bay after unloading a couple former Wahoos — QB at Minnesota Fair. The touchdown-pass crown probably takes a back seat to PRESTIGE Huge. The home run crown is the most hallowed mark in Ameri- Matt Schaub (to Houston) and DE Patrick Kerney 1 p.m. the career rushing yards record. OF RECORD can sports. (Seattle) — and thanks to some rather unwise decisions by a couple former Hokies, Michael DUBIOUSNESS Vick and DeAngelo Hall. BREAKDOWN Negligible. Favre’s streak of 240 consecutive starts is almost su- Epic. At this point, the only people who don’t perhuman, and he admitted to an addiction to pain-kill- OF ACCOMPLISH- think Bonds took steroids also think Michael New York Jets (-3) at Buffalo, 1 p.m. ers several years ago, but he has never been connected MENT Vick will be named the next head of PETA. 3 to steroids. Bills starting QB Trent Edwards, a rookie from Number of Stanford, must feel as if he has spent the past interceptions Surprisingly tepid. -

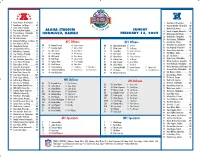

NFC Defense ALOHA STADIUM HONOLULU, HAWAII AFC Offense

4 Adam Vinatieri, New England. K 2 David Akers, Philadelphia. K 9 Drew Brees, San Diego . QB 5 Donovan McNabb, Philadelphia . QB 9 Shane Lechler, Oakland . P 7 Michael Vick, Atlanta . QB 12 Tom Brady, New England. QB ALOHA STADIUM SUNDAY 11 Daunte Culpepper, Minnesota. QB 18 Peyton Manning, Indianapolis . QB HONOLULU, HAWAII FEBRUARY 13, 2005 17 Mitch Berger, New Orleans . P 20 Tory James, Cincinnati . CB 20 Ronde Barber, Tampa Bay . CB 20 Ed Reed, Baltimore . SS 20 Brian Dawkins, Philadelphia . FS 21 LaDainian Tomlinson, San Diego . RB AFC Offense 20 Allen Rossum, Atlanta. KR 22 Nate Clements, Buffalo . CB NFC Offense 21 Tiki Barber, New York Giants . RB 24 Champ Bailey, Denver . CB WR 88 Marvin Harrison 80 Andre Johnson WR 87 Muhsin Muhammad 87 Joe Horn 26 Lito Sheppard, Philadelphia . CB 24 Terrence McGee, Buffalo . CB LT 75 Jonathan Ogden 77 Marvel Smith LT 71 Walter Jones 72 Tra Thomas 30 Ahman Green, Green Bay. RB 32 Rudi Johnson, Cincinnati . RB LG 66 Alan Faneca 54 Brian Waters LG 73 Larry Allen 76 Steve Hutchinson 43 Troy Polamalu, Pittsburgh . SS C 68 Kevin Mawae 64 Jeff Hartings C 57 Olin Kreutz 78 Matt Birk 31 Roy Williams, Dallas . SS 47 John Lynch, Denver . FS RG 68 Will Shields 54 Brian Waters RG 62 Marco Rivera 76 Steve Hutchinson 32 Dre’ Bly, Detroit . CB 49 Tony Richardson, Kansas City . FB RT 78 Tarik Glenn 77 Marvel Smith RT 76 Orlando Pace 72 Tra Thomas 32 Michael Lewis, Philadelphia. SS 51 James Farrior, Pittsburgh . ILB TE 85 Antonio Gates 88 Tony Gonzalez TE 83 Alge Crumpler 82 Jason Witten 33 William Henderson, Green Bay .