THE UNIVERSITY of WINCHESTER Faculty of Humanities and Social

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fordingbridge Town Design Statement 1 1

The Fordingbridge Community Forum acknowledges with thanks the financial support provided by the New Forest District Council and Awards for All towards the production of this report which was designed and printed by Phillips Associates and James Byrne Printing Ltd. CONTENTS LIST ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As an important adjunct to the Fordingbridge 1 Introduction 2 Health Check, work began on a Town Design Statement for Fordingbridge in 2005. A revised 2 Historical context 3 remit resulted in a fresh attempt being made in 2007. To ensure that the ultimate statement would 3 Map of area covered by this Design Statement 5 be a document from the local community, an invi- tation was circulated to many organisations and 4 The Rural Areas surrounding the town 6 individuals inviting participation in the project. Nearly 50 people attended an initial meeting in 5 Street map of Fordingbridge and Ashford 1 9 January 2007, some of whom agreed to join work- ing parties to survey the area. Each working party 6 Map of Fordingbridge Conservation Area 10 wrote a detailed description of its section. These were subsequently combined and edited to form 7 Plan of important views 11 this document. 8 Fordingbridge Town Centre 12 The editors would like to acknowledge the work carried out by many local residents in surveying 9 The Urban Area of Fordingbridge outside the the area, writing the descriptions and taking pho- Town Centre 18 tographs. They are indebted also to the smaller number who attended several meetings to review, 10 Bickton 23 amend and agree the document’s various drafts. -

Estate Management in the Winchester Diocese Before and After the Interregnum: a Missed Opportunity

Proc. Hampshire Field Club Archaeol. Soc. 61, 2006, 182-199 (Hampshire Studies 2006) ESTATE MANAGEMENT IN THE WINCHESTER DIOCESE BEFORE AND AFTER THE INTERREGNUM: A MISSED OPPORTUNITY By ANDREW THOMSON ABSTRACT specific in the case of the cathedral and that, over allocation of moneys, the bishop seems The focus of this article is the management of the to have been largely his own man. Business at episcopal and cathedral estates of the diocese of Win the cathedral was conducted by a 'board', that chester in the seventeenth century. The cathedral is, the dean and chapter. Responsibilities in estates have hardly been examined hitherto and the diocese or at the cathedral, however, were previous discussions of the bishop's estates draw ques often similar if not identical. Whether it was a tionable conclusions. This article will show that the new bishop's palace or a new chapter house, cathedral, but not the bishop, switched from leasing both bishop and cathedral clergy had to think, for 'lives' to 'terms'. Olhenvise, either through neglect sometimes, at least, not just of themselves and or cowardice in the face of the landed classes, neither their immediate gains from the spoils, but also really exploited 'early surrenders' or switched from, of the long term. Money was set aside accord leasing to the more profitable direct farming. Rental ingly. This came from the resources at the income remained static, therefore, with serious impli bishop's disposal - mainly income from his cations for the ministry of the Church. estates - and the cathedral's income before the distribution of dividends to individual canons. -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Mobilizing the Metropolis: Politics, Plots and Propaganda in Civil War London, 1642-1644 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3gh4h08w Author Downs, Jordan Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Mobilizing the Metropolis: Politics, Plots and Propaganda in Civil War London, 1642-1644 A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Jordan Swan Downs December 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Thomas Cogswell, Chairperson Dr. Jonathan Eacott Dr. Randolph Head Dr. J. Sears McGee Copyright by Jordan Swan Downs 2015 The Dissertation of Jordan Swan Downs is approved: ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I wish to express my gratitude to all of the people who have helped me to complete this dissertation. This project was made possible due to generous financial support form the History Department at UC Riverside and the College of Humanities and Social Sciences. Other financial support came from the William Andrew’s Clark Memorial Library, the Huntington Library, the Institute of Historical Research in London, and the Santa Barbara Scholarship Foundation. Original material from this dissertation was published by Cambridge University Press in volume 57 of The Historical Journal as “The Curse of Meroz and the English Civil War” (June, 2014). Many librarians have helped me to navigate archives on both sides of the Atlantic. I am especially grateful to those from London’s livery companies, the London Metropolitan Archives, the Guildhall Library, the National Archives, and the British Library, the Bodleian, the Huntington and the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library. -

Separation of Church and State: a Diffusion of Reason and Religion

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 8-2006 Separation of Church and State: A Diffusion of Reason and Religion. Patricia Annettee Greenlee East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Greenlee, Patricia Annettee, "Separation of Church and State: A Diffusion of Reason and Religion." (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2237. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2237 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Separation of Church and State: A Diffusion of Reason and Religion _________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University __________________ In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History _________________ by Patricia A. Greenlee August, 2006 _________________ Dr. Dale Schmitt, Chair Dr. Elwood Watson Dr. William Burgess Jr. Keywords: Separation of Church and State, Religious Freedom, Enlightenment ABSTRACT Separation of Church and State: A Diffusion of Reason and Religion by Patricia A.Greenlee The evolution of America’s religious liberty was birthed by a separate church and state. As America strides into the twenty first century the origin of separation of church and state continues to be a heated topic of debate. -

Northanger Benefice Profile for an Assistant Priest (House for Duty)

Northanger Benefice Profile For an Assistant Priest (House for Duty) Including: St Nicholas, Chawton, St Peter ad Vincula, Colemore St James, East Tisted, St Leonard, Hartley Mauditt, St Mary the Virgin, East Worldham All Saints, Farringdon, All Saints Kingsley, St Mary the Virgin, Newton Valence, St Mary Magdalene, Oakhanger, St Mary the virgin, Selborne St Nicholas, West Worldham Benefice Profile The Northanger Benefice has 8 parishes: Chawton, East Tisted, East Worldham, Farringdon, Kingsley with Oakhanger, Newton Valence, Selborne and West Worldham with Hartley Mauditt. Each has its own Churchwardens and Parochial Church Council. The Churches are: St Nicholas Chawton St James East Tisted with St Peter ad Vincula, Colemore St Mary the Virgin, East Worldham All Saints, Farringdon All Saints Kingsley with St Mary Magdalene, Oakhanger St Mary the Virgin, Newton Valence St Mary the Virgin, Selborne St Nicholas, West Worldham with St Leonard, Hartley Mauditt Insert map 2 All eight rural Hampshire parishes are close together geographically covering a combined area of approximately 60 square miles to the south of the market town of Alton within the boundary of the newly formed South Downs National Park. The parishes have much in common socially with a high proportion of professionals and retired professionals, but also a strong farming tradition; the total population is around four thousand. The congregations range widely in age from children to those in their nineties, many have lived in the area all their lives. Each parish has its own individual foci for mission, but two areas are shared, the first is to maintain a visible Christian presence in the community. -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT STATUTORY SUPPLEMENT AND AUDITED ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2018 The Cathedral Church of the Holy Trinity, St Peter and St Paul, and of St Swithun in Winchester Annual Report Statutory Supplement and Audited Accounts 2012017777////11118888 Contents 111 Aims and Objectives .................................................................................................. 3 222 Chapter Reports ........................................................................................................ 4 2.1 The Dean .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.2 The Receiver General ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 2.3 Worship ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 6 2.4 Education and Spirituality ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 7 2.5 Canon Principal ............................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Winchester Traveller DPD : Reports to Cabinet (LP) Committee Meeting

Winchester Traveller DPD : Reports to Cabinet (LP) Committee Meeting reference and date Key matters considered CAB2837(LP) 5 October 2016 A programme for preparation of the DPD was reported given the accommodation needs were to be established in LPP2, through a proposed main modification. Presentation of Initial findings on two key evidence reports – site assessments and gypsy and traveller accommodation needs assessment which had recently been completed. CAB2904(LP) 27 February 2017 Further details on the timescale for the preparation of the DPD with LP2 being declared ‘sound’ in January 2017. Feedback on representations received to the ‘commencement notice’ issued during October – December 2016. CAB2947(LP) 30 June 2017 Feedback on initial options consultation held during March – May 2017. Cabinet 5 July 2017 Approval of draft DPD for consultation under Regulation 18 – agreement to explore options to consider the purchasing of land/premises to accommodate the shortfall in provision of sites for travelling showpeople CAB2965(LP) 4 December 2017 Feedback on representations received under Regulation 18 and conclusions of Cabinet 6 December 2017 land search process which did not reveal any suitable sites for purchase. Council 10 January 2018 Approval of amended DPD to publish under Regulation 19 and subsequent submission for examination. CAB2837(LP) FOR DECISION WARD(S): ALL CABINET (LOCAL PLAN) COMMITTEE 5 October 2016 GYPSY AND TRAVELLER NEEDS / SITE ALLOCATIONS DEVELOPMENT PLAN DOCUMENT REPORT OF HEAD OF STRATEGIC PLANNING Contact Officer: -

Diocesan Synod Digest

DIOCESAN SYNOD ACTS 16 March 2017 Acts of the Diocesan Synod held on 16 March 2017 at St Luke’s Hedge End. 70 members were in attendance. The Revd Fiona Gibbs and Mr Nigel Williams led members in opening worship. The Bishop of Winchester welcomed members. AMAP PROPOSALS 2017-1019, DS 17/01 Vision & Implementation of Strategic Priorities The Bishop of Winchester shared an overview of the vision and implementation of the diocesan strategic priorities at a diocesan and archidiaconal level, focusing on sustainable growth for the common good, with the intention to be proactive rather than reactive. Four projects were proposed: 1. Benefice of the Future, Promote Rural Evangelism & Discipleship The Archdeacon of Winchester presented proposals for the Benefice of the Future to be trialled in three benefices initially: Pastrow with Hurstbourne Tarrant & Faccombe & Vernham Dean & Linkenholt; North Hampshire Downs; Avon Valley. 2. Invest Where There is the Greatest Potential for Numerical Growth – Resource Churches Planted, Flourishing and Preparing to Plant Again The Archdeacon of Bournemouth presented proposals for Resource Churches, with initial plans to go into Southampton and Basingstoke, each Resource Church to develop a pipeline to plant other churches. 3. Major Development Areas (MDA) – the Church Supports Sustainable Community Development and Offers a Missional Christian Presence The Bishop of Basingstoke presented an overview of areas across the diocese which will see developments of 250+ houses over the next few years; proposing that the diocese must engage with the new communities as soon as possible to ensure a Christian presence. 4. Further & Higher Education – Grow and Deepen the Church’s Engagement with Students and Institutions The Bishop of Winchester presented members with an overview of Further and Higher Education and the challenges the church faces with engagement. -

Gazetteer.Doc Revised from 10/03/02

Save No. 91 Printed 10/03/02 10:33 AM Gazetteer.doc Revised From 10/03/02 Gazetteer compiled by E J Wiseman Abbots Ann SU 3243 Bighton Lane Watercress Beds SU 5933 Abbotstone Down SU 5836 Bishop's Dyke SU 3405 Acres Down SU 2709 Bishopstoke SU 4619 Alice Holt Forest SU 8042 Bishops Sutton Watercress Beds SU 6031 Allbrook SU 4521 Bisterne SU 1400 Allington Lane Gravel Pit SU 4717 Bitterne (Southampton) SU 4413 Alresford Watercress Beds SU 5833 Bitterne Park (Southampton) SU 4414 Alresford Pond SU 5933 Black Bush SU 2515 Amberwood Inclosure SU 2013 Blackbushe Airfield SU 8059 Amery Farm Estate (Alton) SU 7240 Black Dam (Basingstoke) SU 6552 Ampfield SU 4023 Black Gutter Bottom SU 2016 Andover Airfield SU 3245 Blackmoor SU 7733 Anton valley SU 3740 Blackmoor Golf Course SU 7734 Arlebury Lake SU 5732 Black Point (Hayling Island) SZ 7599 Ashlett Creek SU 4603 Blashford Lakes SU 1507 Ashlett Mill Pond SU 4603 Blendworth SU 7113 Ashley Farm (Stockbridge) SU 3730 Bordon SU 8035 Ashley Manor (Stockbridge) SU 3830 Bossington SU 3331 Ashley Walk SU 2014 Botley Wood SU 5410 Ashley Warren SU 4956 Bourley Reservoir SU 8250 Ashmansworth SU 4157 Boveridge SU 0714 Ashurst SU 3310 Braishfield SU 3725 Ash Vale Gravel Pit SU 8853 Brambridge SU 4622 Avington SU 5332 Bramley Camp SU 6559 Avon Castle SU 1303 Bramshaw Wood SU 2516 Avon Causeway SZ 1497 Bramshill (Warren Heath) SU 7759 Avon Tyrrell SZ 1499 Bramshill Common SU 7562 Backley Plain SU 2106 Bramshill Police College Lake SU 7560 Baddesley Common SU 3921 Bramshill Rubbish Tip SU 7561 Badnam Creek (River -

The Distribution of the Romano-British Population in The

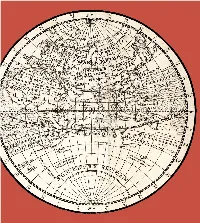

PAPERS AND PROCEEDINGS 119 THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE ROMANO - BRITISH POPULATION IN THE BASINGSTOKE AREA. By SHIMON APPLEBAUM, BXITT., D.PHIL. HE district round Basingstoke offers itself as the subject for a study of Romano-British . population development and. Tdistribution because Basingstoke Museum contains a singu larly complete collection of finds made in this area over a long period of years, and preserved by Mr. G. W. Willis. A number of the finds made are recorded by him and J. R. Ellaway in the Proceedings of the Hampshire Field Club (Vol. XV, 245 ff.). The known sites in the district were considerably multiplied by the field-work of S. E. Winbolt, who recorded them in the Proceedings of the same Society.1 I must express my indebtedness to Mr. G. W. Willis, F.S.A., Hon. Curator of Basingstoke Museum, for his courtesy and assist ance in affording access to the collection for the purposes of this study, which is part of a broader work on the Romano-British rural system.2 The area from which the bulk of the collection comes is limited on the north by the edge of the London Clay between Kingsclere and Odiham ; its east boundary is approximately that, of the east limit of the Eastern Hampshire High Chalk Region' southward to Alton. The south boundary crosses that region through Wilvelrod, Brown Candover and Micheldever, with outlying sites to the south at Micheldever Wood and Lanham Down (between Bighton and Wield). The western limit, equally arbitrary, falls along the line from Micheldever through Overton to Kingsclere. -

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation Sincs Hampshire.Pdf

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINCs) within Hampshire © Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre No part of this documentHBIC may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recoding or otherwise without the prior permission of the Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre Central Grid SINC Ref District SINC Name Ref. SINC Criteria Area (ha) BD0001 Basingstoke & Deane Straits Copse, St. Mary Bourne SU38905040 1A 2.14 BD0002 Basingstoke & Deane Lee's Wood SU39005080 1A 1.99 BD0003 Basingstoke & Deane Great Wallop Hill Copse SU39005200 1A/1B 21.07 BD0004 Basingstoke & Deane Hackwood Copse SU39504950 1A 11.74 BD0005 Basingstoke & Deane Stokehill Farm Down SU39605130 2A 4.02 BD0006 Basingstoke & Deane Juniper Rough SU39605289 2D 1.16 BD0007 Basingstoke & Deane Leafy Grove Copse SU39685080 1A 1.83 BD0008 Basingstoke & Deane Trinley Wood SU39804900 1A 6.58 BD0009 Basingstoke & Deane East Woodhay Down SU39806040 2A 29.57 BD0010 Basingstoke & Deane Ten Acre Brow (East) SU39965580 1A 0.55 BD0011 Basingstoke & Deane Berries Copse SU40106240 1A 2.93 BD0012 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood North SU40305590 1A 3.63 BD0013 Basingstoke & Deane The Oaks Grassland SU40405920 2A 1.12 BD0014 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood South SU40505520 1B 1.87 BD0015 Basingstoke & Deane West Of Codley Copse SU40505680 2D/6A 0.68 BD0016 Basingstoke & Deane Hitchen Copse SU40505850 1A 13.91 BD0017 Basingstoke & Deane Pilot Hill: Field To The South-East SU40505900 2A/6A 4.62 -

Global Encounters and the Archives Global Encounters a Nd the Archives

1 Global Encounters and the Archives Global EncountErs a nd thE archivEs Britain’s Empire in the Age of Horace Walpole (1717–1797) An exhibition at the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University October 20, 2017, through March 2, 2018 Curated by Justin Brooks and Heather V. Vermeulen, with Steve Pincus and Cynthia Roman Foreword On this occasion of the 300th anniversary of Horace In association with this exhibition the library Walpole’s birthday in 2017 and the 100th anniversary will sponsor a two-day conference in New Haven of W.S. Lewis’s Yale class of 2018, Global Encounters on February 9–10, 2018, that will present new and the Archives: Britain’s Empire in the Age of Horace archival-based research on Britain’s global empire Walpole embraces the Lewis Walpole Library’s central in the long eighteenth century and consider how mission to foster eighteenth-century studies through current multi-disciplinary methodologies invite research in archives and special collections. Lewis’s creative research in special collections. bequest to Yale was informed by his belief that “the cynthia roman most important thing about collections is that they Curator of Prints, Drawings and Paintings furnish the means for each generation to make its The Lewis Walpole Library own appraisals.”1 The rich resources, including manuscripts, rare printed texts, and graphic images, 1 W.S. Lewis, Collector’s Progress, 1st ed. (New York: indeed provide opportunity for scholars across Alfred A. Knopf, 1951), 231. academic disciplines to explore anew the complexities and wide-reaching impact of Britain’s global interests in the long eighteenth century Global Encounters and the Archives is the product of a lively collaboration between the library and Yale faculty and graduate students across academic disci- plines.