The Age of Discrepancy. a Cautionary Tale in Un Banquete En Tetlapayac

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reading Eisenstein's Capital

Sergei Eisenstein. Diary entry, February 23, 1928. Rossiiskii Gosudarstevennyi Arkhiv Literatury i Iskusstva ( Russian State Archive for Literature and Art). 94 https://doi.org/10.1162/grey_a_00251 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/grey_a_00251 by guest on 01 October 2021 Dance of Values: Reading Eisenstein’s Capital ELENA VOGMAN “The crisis of the democracy shoUld be Understood as crisis of the conditions of exposition of the political man.” 1 This is how Walter Benjamin, in 1935, describes the decisive political conseqUences of the new medial regime in the “age of technological reprodUcibility.” Henceforth, the political qUestion of representation woUld be determined by aesthetic conditions of presentation. 2 In other words, what is at stake is the visibility of the political man, insofar as Benjamin argUes that “radio and film are changing not only the fUnction of the professional actor bUt, eqUally, the fUnction of those who, like the politician, present themselves before these media.” 3 Benjamin’s text evokes a distorting mirror in which the political man appears all the smaller, the larger his image is projected. As a resUlt, the contemporary capitalist conditions of reprodUction bring forth “a new form of selection”—an apparatUs before which “the champion, the star, and the dictator emerge as victors.” 4 The same condition of technological reprodUction that enables artistic and cUltUral transmission is inseparably tied to the conditions of capi - talist prodUction, on the one hand, and the rise of fascist regimes, on the other. Benjamin was not the first to draw an impetUs for critical analysis from this relationship. -

Russian Byliny As Discursive Space

Putting Words in Their Mouths: Russian Byliny as 83 Discursive Space Putting Words in Their Mouths: Russian Byliny as Discursive Space Kate Christine Moore Koppy Marymount University and the University of the District of Columbia Community College Arlington, Virginia, United States of America Abstract This article follows the Melnitsa Animation Studio into the imagined medieval space of their bogatyr films. With particular focus on Melnitsa’s use of the Il’ia Muromets corpus in Илья Муромец и Соловей Разбойник [Il’ia and the Robber], we consider the complex set of conflicts among characters and ideas that reflect concepts of identity and social issues in contemporary Russia. In moments of cultural unrest, adaptations of canonical stories serve as a discursive space for the community to redefine itself. In the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries, the byliny [western Slavic heroic epics] have functioned as tools of cultural cohesion at critical moments of national self-redefinition. Most recently, the Студия анимационного кино Мельница [Melnitsa Animation Studio] (1) has adapted the byliny into animated films for children, in which stories of medieval princes, heroes, and villains become a discursive space for the exploration of social issues in the post-Soviet Russian Federation. Melnitsa’s 2007 film Il’ia and the Robber is the most recent example in a steady stream of adaptation and retelling of byliny from the time they were first printed to the present. Along that timeline, there are three moments in which adaptations flourish, and each of these coincides with a crucial moment of redefinition of Russian culture. The nineteenth century recording of these heroic epics, which adapts them from dynamic oral epics to written texts (2), was part of the wave of romantic nationalism that drove scholars across Europe to gather folkloric material as the feudal city-states of the medieval period coalesced into more stable nations. -

Visual Metaphors for the People a Study of Cinematic Propoganda in Sergei Eisenstein’S Film

VIsual Metaphors for the people A Study of Cinematic Propoganda in Sergei Eisenstein’s Film ashley brown This paper attempTs To undersTand how The celebraTed and conTroversial figure of sergei eisensTein undersTood and conTribuTed To The formaTion of The sovieT union Through his films of The 1920s. The lens of visual meTaphors offer a specific insighT inTo how arTisTic choices of The direcTor were informed by his own pedagogy for The russian revoluTion. The paper asks The quesTions: did eisensTein’s films reflecT The official parTy rheToric? how did They inform or moTivaTe The public Toward The communisT ideology of The early sovieT union? The primary sources used in This pa- per are from The films Strike (1925), BattleShip potemkin (1926), octoBer (1928), and the General line (1929). eisensTein creaTed visual meTaphors Through The juxTaposi- Tion of images in his films which alluded To higher concepTs. a shoT of a worker followed by The shoT of gears Turning creaTed The concepT of indusTry in The minds of The audience. Through visual meTaphors, iT is possible To undersTand The moTives of eisensTein and The communisT parTy. iT is also possible, wiTh The aid of secondary sources, To see how Those moTives differed. “Language is much closer to film than painting is. For example, aimed at the “... organization of the psychology of the in painting the form arises from abstract elements of line and masses.”6 Works about Eisenstein in the field of film color, while in cinema the material concreteness of the image theory examine Eisenstein’s career in theater, the evolution within the frame presents—as an element—the greatest of his approach to montage, and his artistic expression.7 difficulty in manipulation. -

Soviet Cinema: Art and Politics from the Avant-Garde to the Return of the Stalinist Repressed

SOVIET CINEMA: ART AND POLITICS FROM THE AVANT-GARDE TO THE RETURN OF THE STALINIST REPRESSED PROF. DANIEL SCHWARTZ RUSS 395 WINTER 2021 COURSE DESCRIPTION The history of Soviet cinema traces the conflicting ideologies and social anxieties of the USSR. This course aims to acquaint students with these ideologies and anxieties through the films of major and minor Soviet directors. It offers a broad survey of the pivotal transformations of Soviet cinema from the pre-Soviet silent era through the Russian avant- garde (1920s), Socialist Realism (1930s and 40s), New Wave (1950s and 60s), Stagnation (1970s), Perestroika and the fall of communism (1980s). Special attention will be given to women and minority filmmakers including Larissa Shepitko, Kira Muratova, and Sergei Parajanov. Key questions we will ask include: How does film function as propaganda or entertainment? How does it foster a multi-ethnic Soviet community? What are the political implications of a film’s stylistic choices? By the end of the course, students will be able to situate Soviet films in their cultural, historical, and theoretical contexts. BASIC INFORMATION Professor: Daniel Schwartz ([email protected]) Office Hours: Thursday, 17:30 – 19:30, or by appointment. REQUIRED READING All Readings will be made available on My Courses Students must have read the readings before class meets / as necessary to complete assignments. REQUIRED FILMS Film for this class are available on various streaming platforms including Kanopy, YouTube, and Amazon. McGill has a subscription to Kanopy that is available to all students. Login at https://mcgill.kanopy.com. Unfortunately, McGill does not have online access to every film I wish to show for this course. -

Depictions of Women in Stalinist Sovet Film, 1934-1953

University of Central Florida STARS HIM 1990-2015 2012 Depictions of women in stalinist sovet film, 1934-1953 Andrew Weeks University of Central Florida Part of the European History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015 University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIM 1990-2015 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Weeks, Andrew, "Depictions of women in stalinist sovet film, 1934-1953" (2012). HIM 1990-2015. 1375. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015/1375 Depictions of Women in Stalinist Soviet Film, 1934-1953 By Andrew Glen Weeks A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in History in the College of Arts and Humanities and in the Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2012 Thesis Chair: Dr. Vladimir Solonari Abstract Popular films in the Soviet Union were the products the implementation of propagandistic messages into storylines that were both ideologically and aesthetically consistent with of the interests of the State and Party apparatuses. Beginning in the 1930s, following declaration of the doctrine on socialist realism as the official form of cultural production, Soviet authorities and filmmakers tailored films to the circumstances in the USSR at that given moment in order to influence and shape popular opinion; however, this often resulted in inconsistent and outright contradictory messages. -

The Pre-Revolutionary Folk Tale Character Archetypes in Grigori Aleksandrov's Four Musical Comedies, 1934 – 1940

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Trepo - Institutional Repository of Tampere University UNIVERSITY OF TAMPERE RIKU SALMIVUORI FROM BOYARS TO BUREAUCRATS: THE PRE-REVOLUTIONARY FOLK TALE CHARACTER ARCHETYPES IN GRIGORI ALEKSANDROV'S FOUR MUSICAL COMEDIES, 1934 – 1940 ___________________________________ School of Social Sciences and Humanities Master's thesis in history Tampere, 2014 University of Tampere School of Social Sciences and Humanities SALMIVUORI, RIKU: From Boyars to Bureaucrats: The Pre-revolutionary Folk Tale Character Archetypes in Grigori Aleksandrov's Four Musical Comedies, 1934 – 1940 Master's thesis, 138 pages. History February 2014 In my master's thesis I study the society of the 1930s Soviet Union through its film culture's relation to the pre-revolutionary folk culture's traditional tale telling. My aim is to find out how the pre- revolutionary culture was reflected in the films. On the one hand the study approaches this question through the official Soviet concepts of the 1930s: the attempt to build a “new society” and through education create a whole “new man”. On the other hand, it supposes that hundreds of years of folk tradition will not simply vanish by the politicians setting such ambitious political aims. Therefore the aim is to study the films, a popular tool of education and definitely a representative of the officially sanctioned culture, in order to find out what traces were left of the pre-revolutionary culture in them and how they were used in the films. The conclusions drawn on this small sample can further be used to consider what actually was new in the new society and the new man. -

Nuclear Weapons, Propaganda, and Cold War Memory Expressed in Film: 1959-1989 Michael A

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2016 Their swords, our plowshares: "Peaceful" nuclear weapons, propaganda, and Cold War memory expressed in film: 1959-1989 Michael A. St. Jacques James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the Cultural History Commons, Defense and Security Studies Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Political History Commons, and the Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies Commons Recommended Citation St. Jacques, Michael A., "Their swords, our plowshares: "Peaceful" nuclear weapons, propaganda, and Cold War memory expressed in film: 1959-1989" (2016). Masters Theses. 102. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/102 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Their Swords, Our Plowshares: "Peaceful" Nuclear Weapons, Propaganda, and Cold War Memory Expressed in Film: 1949-1989 Michael St. Jacques A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History May 2016 FACULTY COMMITTEE: Committee Chair: Dr. Steven Guerrier Committee Members/ Readers: Dr. Maria Galmarini Dr. Alison Sandman Dedication For my wife, my children, my siblings, and all of my family and friends who were so supportive of me continuing my education. At the times when I doubted myself, they never did. -

Visualizing Vertov

Lev Manovich Visualizing Vertov "To represent a dynamic study on a sheet of paper, we need graphic symbols of movement." Dziga Vertov, "We: The variant of the manifesto" (1920), in Kino-Eye: the writings of Dziga Vertov, ed. Annette Michelson, trans. Kevin O’Brien (University of California Press, 1984), p.7. High-resolution versions of all visualizations appearing in this text are available on Flickr for download: http://www.flickr.com/photos/culturevis/sets/72157632441192048/with/8349174610/ This project presents visualization analysis of the films The Eleventh Year (1928) and Man with a Movie Camera (1929) by the famous Russian filmmaker Dziga Vertov. It uses experimental visualization techniques [1] that complement familiar bar charts and line graphs often found in quantitative studies of cultural artifacts. The digital copies of the films were provided by The Austrian Film Museum (Vienna). Visualization gives us new ways to study and teach cinema, as well as other visual time-based media such as television, user-generated video, motion graphics, and computer games. The project is a part of a larger research program to develop techniques for the exploration of massive image and video collections that I have been directing at Software Studies Initiative (softwarestudies.com) since 2007 [2]. In this project, I explore how “media visualization” techniques we developed can help us see films in new ways, supplementing already well-developed methods and tools in film and media studies. Its other goal is to make a bridge between the two fields which at present are not connected: the field of digital humanities which is interested in new data visualization techniques, but does not study cinema, and quantitative film studies research which until now has used graphs in a more limited way. -

The Spatial Cosmology of the Stalin Cult: Ritual, Myth and Metanarrative

Anderson, Jack (2018) The spatial cosmology of the Stalin Cult: ritual, myth and metanarrative. MRes thesis. https://theses.gla.ac.uk/30631/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] School of History, College of Arts University of Glasgow The Spatial Cosmology of the Stalin Cult Ritual, Myth and Metanarrative Jack Anderson Submitted in the fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of MRes in History To my Mum, Gran and Grandad – without their support I would not have been able to study. Thanks to Ryan and Robyn for proof reading my work at numerous stages. And also, to my supervisors Maud and Alex, for engaging with my area of study; their input and guidance has been intellectually stimulating throughout my time at Glasgow. 2 Abstract: This paper will focus on Stalin’s use of Soviet space throughout the 1930s and the relationship this had with the developing Stalin cult. In the thirties, Stalin had consolidated power and from as early as 1929 the Stalin cult was beginning to emerge. -

Jun & Jul Guide

VISIT home box office HOME mcr. 0161 200 1500 2 Tony Wilson Place DON’T MISS... Manchester org THEATRE ART YOUNG M15 4FN home EXHIBITION/ LA MOVIDA INFORMATION & HOME presents Until Mon 17 Jul PEOPLE ROSE Free, drop in BOOKING Until Sat 10 Jun YOUNG IDENTITY homemcr.org/la-movida HOMEmcr.org Tickets £26.50 - £10 Every Monday, 19:00 0161 200 1500 homemcr.org/rose (excluding Bank Holidays) EXHIBITION TOUR: LA MOVIDA Free, drop in [email protected] Accessible Performances Thu 1 Jun, 18:30 homemcr.org/young-identity BSL Interpreted Free, booking required Tue 6 Jun, 19:30 homemcr.org/la-movida ACCESSIBILITY HOMEmcr.org/accessibility Caption Subtitled HOME PROJECTS: EDEN KÖTTING REGULAR Wed 7 Jun, 19:30 & ANONYMOUS BOSCH TOUCH Audio Described Touch Wed 21 Jun – Sun 30 Jul EVENTS KEEP IN TOUCH TOUR Tour Granada Foundation Galleries 1 & 2 PLAYREADING Twitter @HOME_mcr Thu 8 Jun, 18:30 Free, drop in Fri 2 Jun, 11:00 Facebook HOMEmcr homemcr.org/home-projects Audio Described Fri 7 Jul, 11:00 Instagram HOMEmcr Thu 8 Jun, 19:30 Tickets £5 (scripts and CEREMONY Audioboom HOMEmcr refreshments included) Event/ Playreading: The Shroud PART OF MIF17 homemcr.org/playreading Youtube HOMEmcrorg Maker + Q&A with Palestinian Sun 16 Jul, 18:00 writer Ahmed Masoud Free, booking required JMK RESIDENCY Fri 9 Jun, 19:00 homemcr.org/ceremony OPENING TIMES Wed 7 – Fri 9 Jun, 10:00 – 17:00 Tickets £3 Box Office homemcr.org/shroud-maker Free, application required homemcr.org/jmk-jun Mon – Sun: 12:00 – 20:00 creatives Main Gallery Blast Theory and Hydrocracker MOTHERS -

SFSFF 2018 Program Book

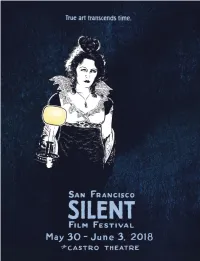

elcome to the San Francisco Silent Film Festival for five days and nights of live cinema! This is SFSFFʼs twenty-third year of sharing revered silent-era Wmasterpieces and newly revived discoveries as they were meant to be experienced—with live musical accompaniment. We’ve even added a day, so there’s more to enjoy of the silent-era’s treasures, including features from nine countries and inventive experiments from cinema’s early days and the height of the avant-garde. A nonprofit organization, SFSFF is committed to educating the public about silent-era cinema as a valuable historical and cultural record as well as an art form with enduring relevance. In a remarkably short time after the birth of moving pictures, filmmakers developed all the techniques that make cinema the powerful medium it is today— everything except for the ability to marry sound to the film print. Yet these films can be breathtakingly modern. They have influenced every subsequent generation of filmmakers and they continue to astonish and delight audiences a century after they were made. SFSFF also carries on silent cinemaʼs live music tradition, screening these films with accompaniment by the worldʼs foremost practitioners of putting live sound to the picture. Showcasing silent-era titles, often in restored or preserved prints, SFSFF has long supported film preservation through the Silent Film Festival Preservation Fund. In addition, over time, we have expanded our participation in major film restoration projects, premiering four features and some newly discovered documentary footage at this event alone. This year coincides with a milestone birthday of film scholar extraordinaire Kevin Brownlow, whom we celebrate with an onstage appearance on June 2. -

Eisenstein's “Dynamic Square”

[ 10 ] The Screen as “Battleground”: Eisenstein’s “Dynamic Square” and the Plasticity of the Projection Format Antonio Somaini Thequestionoftherelationsbetweenthethreeconceptsofformat, medium,anddispositifisraisedbydifferent,pre-andpost-digitalwaysof understandingtheterm“format.”Ifwefocusinparticularonthehistoryof cinema,wecanstudytherelationbetweenthesethreetermsbyreferring toatleastthreedifferentmeaningsof“format,”indicating,respectively, thesizeofthephotosensitiveareaofaframewithinacelluloidfilm(8mm, 16mm,35mm,70mm,etc.),theaspectratioofaprojectedimage,andthe wayinwhichadigitalmovingimagefileisencodedforstorage,process- ing,transmissionanddisplay,oftenthroughsomekindofcompression. Inallthreecases,whatemergesisthecloselinkbetweentheconceptsof “format”and“form”:moreprecisely,between“format”andtheprocess of“givingastandardizedform” (inthesenseof“formatting”)tovisual phenomenabycapturing,storing,andorganizingthemthroughspecific materialsupports,procedures,andtechniquesthatwillconditiontheway theywillbecomevisibleagainthroughsomekindofvisualoraudiovisual dispositif. JonathanSterne’s(2012,8)definitionoftheformatas“whatspecifies theprotocolsbywhichamediumwilloperate”,originallyformulated inthecontextofastudyonthehistoryoftheaudioMP3format,may alsoapplytothethreemeaningsofformatwejustmentioned.Thesize ofthephotosensitiveareaofaframewithinacelluloidfilm,theaspect