Madness with a Straight Face: John Miller July 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exhibitions in 2019 January 19

Press contacts: Sonja Hempel (exhibitions) Tel. +49 221 221 23491 [email protected] Anne Niermann (general inquiries) Tel. +49 221 221 22428 [email protected] Exhibitions in 2019 January 19 – April 14, 2019 Hockney/Hamilton: Expanded Graphics New Acquisitions and Works from the Collection, with Two Films by James Scott Press conference: Friday, January 18, 2019, 11 a.m., press preview starting at 10 a.m. March 9 – June 2, 2019 Nil Yalter: Exile Is a Hard Job Opening: Friday, March 8, 2019, 7 p.m. Press conference: Thursday, March 7, 2019, 11 a.m., press preview starting at 10 a.m. April 10 – July 21, 2019 2019 Wolfgang Hahn Prize: Jac Leirner Award ceremony and opening: Tuesday, April 9, 2019, 6:30 p.m. Press conference: Tuesday, April 9, 2019, 11 a.m., press preview starting at 10 a.m. May 4 – August 11, 2019 Fiona Tan: GAAF Part of the Artist Meets Archive series Opening: Friday, May 3, 2019, 7 p.m. Press conference: Thursday, May 2, 2019, 11 a.m., press preview starting at 10 a.m. July 13 – September 29, 2019 Family Ties: The Schröder Donation Opening: Friday, July 12, 2019, 7 p.m. Press conference: Thursday, July 11, 2019, 11 a.m., press preview starting at 10 a.m. September 21, 2019 – January 19, 2020 HERE AND NOW at Museum Ludwig Transcorporealities Opening: Friday, September 20, 2019, 7 p.m. Press conference: Friday, September 20, 2019, 11 a.m., press preview starting at 10 a.m. November 16, 2019 – March 1, 2020 Wade Guyton Opening: Friday, November 15, 2019, 7 p.m. -

Glaser NYT Article 2020-03-27

nytimes.com Swiss Museum Settles Claim Over Art Trove Acquired in Nazi Era Catherine Hickley 6-7 minutes The Kunstmuseum in Basel agreed to pay the heirs of a Berlin collector for 200 works he sold as he fled German persecution of Jews. Credit...Julian Salinas Twelve years after the city of Basel, Switzerland, rejected a claim for restitution of 200 prints and drawings in its Kunstmuseum, officials there have reversed their position and reached a settlement with the heirs of a renowned Jewish museum director and critic who sold his collection before fleeing Nazi Germany. In 2008, the museum argued that the original owner, Curt Glaser, a leading figure in the Berlin art world and close friend of Edvard Munch, sold the art at market prices. The museum’s purchase of the works at a 1933 auction in Berlin was made in good faith, it said, so there was no basis for restitution. But after the Swiss news media unearthed documents that shed doubt on that version of events, the museum reviewed its earlier decision and today announced it would pay an undisclosed sum to Glaser’s heirs. In return, it will keep works on paper estimated to be worth more than $2 million by artists including Henri Matisse, Max Beckmann, Auguste Rodin, Marc Chagall, Oskar Kokoschka, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Erich Heckel. Among the most valuable pieces are two Munch lithographs, “Self Portrait” and “Madonna.” The turnaround is a major victory for the heirs but also a sign, experts said, of a new willingness on the part of Swiss museums to engage seriously with restitution claims and apply international standards on handling Nazi-looted art in public collections. -

Robert Indiana

ROBERT INDIANA Born in New Castle, Indiana in 1928 and died in 2018 Robert Indiana adopted the name of his home state after serving in the US military. The artist received his BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1954 and following the advice of his friend Ellsworth Kelly, he relocated to New York, setting up a studio in the Coenties Slip neighborhood of Lower Manhattan and joined the pop art movement. The work of the American Pop artist Robert Indiana is rooted in the visual idiom of twentieth-century American life with the same degree of importance and influence as Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. As a self-proclaimed “American painter of signs” Indiana gained international renown in the early 1960’s, he drew inspiration from the American road and shop signs, billboards, and commercial logos and combined it with a sophisticated formal and conceptual approach that turned a familiar vocabulary into something entirely new, his artworks often consists of bold, simple, iconic images, especially numbers and short words like “EAT”, “HOPE”, and “LOVE” what Indiana called “sculptural poems”. The iconic work “LOVE”, served as a print image for the Museum of Modern Art ‘s Christmas card in 1964 and sooner later the design became popular as US postage stamp. “LOVE” has also appeared in prints, paintings, sculptures, banners, rings, tapestries. Full of erotic, religious, autobiographical, and political undertones — it was co-opted as an emblem of 1960s idealism (the hippie free love movement). Its original rendering in sculpture was made in 1970 and is displayed in Indiana at the Indianapolis Museum of Art. -

Gerhard Richter

GERHARD RICHTER Born in 1932, Dresden Lives and works in Cologne EDUCATION 1951-56 Studied painting at the Fine Arts Academy in Dresden 1961 Continued his studies at the Fine Arts Academy in Düsseldorf 2001 Doctoris honoris causa of the Université Catholique de Louvain-la-Neuve SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2017 About Painting S.M.A.K Museum of Contemporary Art, Ghent 2016 Selected Editions, Setareh Gallery, Düsseldorf 2014 Pictures/Series. Fondation Beyeler, Riehen 2013 Tepestries, Gagosian, London 2012 Unique Editions and Graphics, Galerie Löhrl, Mönchengladbach Atlas, Kunsthalle im Lipsiusbau, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Dresden Das Prinzip des Seriellen, Galerie Springer & Winckler, Berlin Panorama, Neue und Alte Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin Editions 1965–2011, me Collectors Room, Berlin Survey, Museo de la Ciudad, Quito Survey, Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango del Banco de la República, Bogotá Seven Works, Portland Art Museum, Portland Beirut, Beirut Art Center, Beirut Painting 2012, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, NY Ausstellungsraum Volker Bradtke, Düsseldorf Drawings and Watercolours 1957–2008, Musée du Louvre, Paris 2011 Images of an Era, Bucerius Kunst Forum, Hamburg Sinbad, The FLAG Art Foundation, New York, NY Survey, Caixa Cultural Salvador, Salvador Survey, Caixa Cultural Brasilia, Brasilia Survey, Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo Survey, Museu de Arte do Rio Grande do Sul Ado Malagoli, Porto Alegre Glass and Pattern 2010–2011, Galerie Fred Jahn, Munich Editions and Overpainted Photographs, -

Terra Foundation Collection Research Fellow in American Art in Museum Ludwig, City of Cologne, Germany

Terra Foundation Collection Research Fellow in American Art in Museum Ludwig, City of Cologne, Germany The Museum Ludwig—a museum of the City of Cologne, Germany—is one of the most important museums of modern and contemporary art in Europe. Collection strengths include pop art, classical Modernism, Russian Avant-garde, the art of Pablo Picasso, and important works of contemporary art and photography by U.S. artists. Funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art, the Museum Ludwig in Cologne offers a two-year Fellowship for the study/research of Museum Ludwig’s collection of American Art made before 1980. This is a research grant from the Terra Foundation for American Art, based in Chicago and Paris, which supports the study and understanding of American art world wide. The Fellow will research the Museum’s collection of pre-1980 American art, exploring archives in and outside the museum. The orientation of the research should ideally be focused on issues from postcolonial, gender, and/or queer studies, and the outcomes are to be developed so that they are accessible to the general public. Results of the research will be presented in a blog, which is intended to enhance an ongoing dialogue about post-war American art in Europe. In addition, the Fellow will organize a symposium to provide a forum for international scholarly exchange. Finally, in consultation and collaboration with the museum’s curators, the Fellow will participate in the elaboration of an altered presentation of the permanent collection on the basis of archival material and research results. The Fellow will be considered a professional member of the museum’s curatorial staff with ready access to curators, conservators, and other museum departments. -

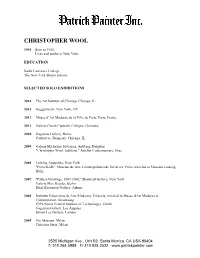

Christopher Wool

CHRISTOPHER WOOL 1955 Born in 1955. Lives and works in New York. EDUCATION Sarah Lawrence College The New York Studio School. SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2014 The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL 2013 Guggenheim, New York, NY 2012 Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, France 2011 Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany 2010 Gagosian Gallery, Rome Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, IL 2009 Galerie Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp, Belgium "Christopher Wool: Editions," Artelier Contemporary, Graz 2008 Luhring Augustine, New York "Porto-Köln," Museum de Arte Contemporanea de Serralves, Porto, traveled to Museum Ludwig, Köln; 2007 "Pattern Paintings, 1987-2000," Skarstedt Gallery, New York Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin Eleni Koroneou Gallery, Athens 2006 Instituto Valenciano de Arte Moderno, Valencia; traveled to Musee d'Art Moderne et Contemporain, Strasbourg ETH (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology), Zurich Gagosian Gallery, Los Angeles Simon Lee Gallery, London 2005 Gio Marconi, Milan Christian Stein, Milan 2525 Michigan Ave., Unit B2, Santa Monica, CA USA 90404 T/ 310 264 5988 F/ 310 828 2532 www.patrickpainter.com 2004 Camden Arts Centre, London Galerie Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp Luhring Augustine, New York Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo 2003 Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne 2002 "Crosstown Crosstown," Le consortium, Dijon; traveled to Dundee Contemporary Arts, Dundee, Scotland Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin 2001 "9th Street Run Down," 11 Duke Street, London; traveled to Galerie Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp Secession, Vienna Luhring Augustine, -

One Hundred Drawings One Hundred Drawings

One hundred drawings One hundred drawings This publication accompanies an exhibition at the Matthew Marks Gallery, 523 West 24th Street, New York, Matthew Marks Gallery from November 8, 2019, to January 18, 2020. 1 Edgar Degas (1834 –1917) Étude pour “Alexandre et Bucéphale” (Study for “Alexander and Bucephalus”), c. 1859–60 Graphite on laid paper 1 1 14 ∕8 x 9 ∕8 inches; 36 x 23 cm Stamped (lower right recto): Nepveu Degas (Lugt 4349) Provenance: Atelier Degas René de Gas (the artist’s brother), Paris Odette de Gas (his daughter), Paris Arlette Nepveu-Degas (her daughter), Paris Private collection, by descent Edgar Degas studied the paintings of the Renaissance masters during his stay in Italy from 1856 to 1859. Returning to Paris in late 1859, he began conceiving the painting Alexandre et Bucéphale (Alexander and Bucephalus) (1861–62), which depicts an episode from Plutarch’s Lives. Étude pour “Alexandre et Bucéphale” (Study for “Alexander and Bucephalus”) consists of three separate studies for the central figure of Alexandre. It was the artist’s practice to assemble a composition piece by piece, often appearing to put greater effort into the details of a single figure than he did composing the work as a whole. Edgar Degas, Alexandre et Bucéphale (Alexander and Bucephalus), 1861–62. Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, bequest of Lore Heinemann in memory of her husband, Dr. Rudolf J. Heinemann 2 Odilon Redon (1840 –1916) A Man Standing on Rocks Beside the Sea, c. 1868 Graphite on paper 3 3 10 ∕4 x 8 ∕4 inches; 28 x 22 cm Signed in graphite (lower right recto): ODILON REDON Provenance: Alexander M. -

Exhibition Program 2021

Pressekontakte: Sonja Hempel (Ausstellungen) Tel +49 221 221 23491 [email protected] Anne Niermann (Allgemeine Anfragen) Tel +49 221 221 22428 [email protected] Exhibitions 2021 March 25 – June 27, 2021 2020 Wolfgang Hahn Prize. Betye Saar March 27 - July 11, 2021 In situ: Photostories on Migration June 12 – August 8, 2021 Green Modernism: The New View of Plants August 21, 2021 – January 23, 2022 HERE AND NOW at Museum Ludwig together for and against it September 3, 2021 – January 9, 2022 Boaz Kaizman September 25, 2021 – January 30, 2022 Picasso, shared and divided The Artist and his Image in the FRG and GDR November 6, 2021 – November 2023 Schultze Projects #3 – Minerva Cuevas November 17, 2021 – February 20, 2022 2021 Wolfgang Hahn Prize. Marcel Odenbach Presentations in the Photography Room March 12 - July 4, 2021 August & Marta How August Sander photographed the painter Marta Hegemann (and her children’s room!) A presentation for children July 30 – November 21, 2021 Voice-Over Felice Beato in Japan December 10, 2021 – March 27, 2022 Raghubir Singh. Kolkata Betye Saar. Wolfgang Hahn Prize 2020 Award ceremony and opening: Tuesday March 24 2021, 6:30 p.m. Presentation: March 25 - June 27, 2021 Due to the Corona Pandemic the award ceremony and the presentation of Betye Saar’s work will be postponed to spring 2021. On March 24, 2021 the american artist will be awarded the twenty- sixth Wolfgang Hahn Prize from the Gesellschaft für Moderne Kunst. This recognition of the artist, who was born in Los Angeles in 1926 and is still little known in Germany, is highly timely, the jury consisting of; Christophe Cherix, Robert Lehman Foundation chief curator of drawings and prints at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York; Yilmaz Dziewior, director of the Museum Ludwig and the board members of the association decided. -

Museum Ludwig, Cologne

MUSEUM LUDWIG, COLOGNE Installation view, Russian Avant-Garde at the Museum Ludwig: Original and Fake. Questions, Research, Explanations, Museum Ludwig, Cologne, 2020. Photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln/Cologne, Chrysant Scheewe. Russian Avant-Garde at the Museum Ludwig: Original and Fake. Questions, Research, Explanations September 26, 2020–January 3, 2021 Digital opening: September 25, live on Instagram @museumludwig at 7pm CEST Museum Ludwig, Cologne Heinrich-Böll-Platz 50667 Cologne Germany Hours: Tuesday–Sunday 10am–6pm www.museum-ludwig.de After a long period in which it was taboo, an increasing number of museums are becoming more transparent about how they deal with inauthentic works and exchanging knowledge. With a studio exhibition on the Russian avant-garde, the Museum Ludwig is presenting research on the authenticity of works in its collection. Thanks to Peter and Irene Ludwig, in addition to Pop Art and Picasso, the Russian avant-garde is a core focus of the museum’s collection, with more than 600 works from the period between 1905 and 1930, including some 100 paintings. For various reasons, works of questionable authorship have continually found their way into private and institutional collections. Works by Russian avant-garde artists were counterfeited particularly often (due to their delayed reception after Stalinism, for instance). Even recently, paintings from this era that have turned out to be inauthentic have been presented in museums. The Museum Ludwig is also affected and is currently systematically investigating its collection of paintings with the help of international scholars. This research represents an important contribution to the international discourse on the Russian avant-garde. -

Christopher Williams Born 1956 in Los Angeles

This document was updated March 3, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. Christopher Williams Born 1956 in Los Angeles. Lives and works in Cologne, Chicago, and Los Angeles. EDUCATION & TEACHING 2008 - present Professor, Kunstakademie Düsseldorf 1981 M.F.A., California Institute of the Arts, Valencia 1978 B.F.A., California Institute of the Arts, Valencia SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 Christopher Williams: Footwear (Adapted for Use), David Zwirner, New York 2019 Christopher Williams - MODEL: Kochgeschirre, Kinder, Viet Nam (Angepasst zum Benutzen), C/O Berlin 2018 Christopher Williams: Normative Models, Kestner Gesellschaft, Hanover [catalogue] 2017 Christopher Williams: Books Plus, ARCHIV, Zurich Christopher Williams: Models, Open Letters, Prototypes, Supplements, La Triennale di Milano, Milan Chirstopher Williams: Open Letter: The Family Drama Refunctioned? (From the Point of View of Production), David Zwirner, London Christopher Williams. Stage Play. Supplements, Models, Prototypes, Miller’s, Zurich [organized by gta exhibitions, ETH Zurich] Christopher Williams: Supplements, Models, Prototypes, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago Christopher Williams: Supplements, Models, Prototypes, ETH Zurich, Institute gta, Zurich 2016 Christopher Williams, Capitain Petzel, Berlin 2014 Christopher Williams. For Example: Dix-Huit Leçons Sur La Société Industrielle (Revision 19), David Zwirner, New York [artist publication] Christopher Williams: The Production Line of Happiness, Art Institute of Chicago [itinerary: The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Whitechapel Gallery, London] [catalogue] Christopher Williams: The Production Line of Happiness, Galerie Mezzanin, Vienna Christopher Williams: The Production Line of Happiness, Musée d’art moderne et contemporain (MAMCO), Geneva [part of Des histoires sans fin/Endless stories series] 2013 Christopher Williams, Volker Bradtke, Düsseldorf Christopher Williams. -

G a G O S I a N Balthus (Balthasar Klossowski De Rola) Biography

G A G O S I A N Balthus (Balthasar Klossowski de Rola) Biography Born in 1908 in Paris, France. Died in 2001 in Rossinière, Switzerland. Selected Solo Exhibitions: 2019 Balthus. Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Spain. 2018 Balthus. Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Switzerland. 2017 Balthus. Gagosian, Geneva, Switzerland. 2016 Balthus. Kunstforum, Vienna, Austria. 2015 Balthus. Scuderie del Quirinale and Villa Medici, Rome, Italy. Balthus. Gagosian Gallery, Hong Kong, Balthus. Gagosian Gallery, Paris, France. 2014 Balthus: A Retrospective. Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Art, Tokyo, Japan. 2013 Balthus: The Last Studies. Gagosian Gallery (976 Madison Ave), New York, NY. Balthus: Cats and Girls—Paintings and Provocations. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY. 2008 Balthus: 100th Anniversary. Fondation Pierre Gianadda, Martigny, Switzerland. 2007 Balthus: Time Suspended. Paintings and Drawings 1932–1960. Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany. 2002 Balthus: Piero della Francesca Alberto Giacometti. Musée Jenisch à Vevey, Vevey, Switzerland. 2001 Balthus. Palazzo Grassi, Venice, Italy. Balthus Remembered. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY. 1999 Balthus: Un Atelier Dans Le Morvan, 1953–1961. Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, Dijon, France. 1996 Omaggio a Balthus. Accademia Valentino, Rome, Italy. Works on paper by Balthus. The Lefevre Gallery, London, England. Balthus. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid, Spain. 1995 Balthus. Palace of Fine Arts, Beijing, China. Balthus. Hong Kong Musuem of Art, Hong Kong, China. 1994 Le Chat au Miroir III by Balthus. Lefevre Gallery, London, England. Balthus: Zeichnungen. Kunstmuseum Bern, Bern Switzerland. 1993 Balthus. Tokyo Station Gallery, Tokyo, Japan. Balthus. Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts, Lausanne, Switzerland. 1992 Balthus dans la maison de Courbet. -

Expressionism in Germany and France: from Van Gogh to Kandinsky

LACM A Exhibition Checklist Expressionism in Germany and France: From Van Gogh to Kandinsky Cuno Amiet Mutter und Kind im Garten (Mother and Child in Garden) (circa 1903) Oil on canvas Canvas: 27 11/16 × 24 3/4 in. (70.4 × 62.8 cm) Frame: 32 1/2 × 28 9/16 × 2 1/4 in. (82.5 × 72.5 × 5.7 cm) Kunstmuseum Basel Cuno Amiet Bildnis des Geigers Emil Wittwer-Gelpke (1905) Oil on canvas Canvas: 23 13/16 × 24 5/8 in. (60.5 × 62.5 cm) Frame: 27 3/4 × 28 9/16 × 2 5/8 in. (70.5 × 72.5 × 6.7 cm) Kunstmuseum Basel Pierre Bonnard The Mirror in the Green Room (La Glace de la chambre verte) (1908) Oil on canvas Canvas: 19 3/4 × 25 3/4 in. (50.17 × 65.41 cm) Frame: 27 × 33 1/8 × 1 1/2 in. (68.58 × 84.14 × 3.81 cm) Indianapolis Museum of Art Georges Braque Paysage de La Ciotat (1907) Oil on canvas Overall: 14 15/16 x 18 1/8 in. (38 x 46 cm) K20 Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen Georges Braque Violin et palette (Violin and Palette) (1909-1910) Oil on canvas Canvas: 36 1/8 × 16 7/8 in. (91.76 × 42.86 cm) Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Heinrich Campendonk Harlequin and Columbine (1913) Oil on canvas Canvas: 65 × 78 3/8 in. (165.1 × 199.07 cm) Frame: 70 15/16 × 84 3/16 × 2 3/4 in. (180.2 × 213.8 × 7 cm) Saint Louis Art Museum Page 1 Paul Cézanne Grosses pommes (Still Life with Apples and Pears) (1891-1892) Oil on canvas Canvas: 17 5/16 × 23 1/4 in.