Guide to Pesach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Debate Over Mixed Seating in the American Synagogue

Jack Wertheimer (ed.) The American Synagogue: A Sanctuary Transformed. New York: Cambridge 13 University Press, 1987 The Debate over Mixed Seating in the American Synagogue JONATHAN D. SARNA "Pues have never yet found an historian," John M. Neale com plained, when he undertook to survey the subject of church seating for the Cambridge Camden Society in 1842. 1 To a large extent, the same situation prevails today in connection with "pues" in the American syn agogue. Although it is common knowledge that American synagogue seating patterns have changed greatly over time - sometimes following acrimonious, even violent disputes - the subject as a whole remains unstudied, seemingly too arcane for historians to bother with. 2 Seating patterns, however, actually reflect down-to-earth social realities, and are richly deserving of study. Behind wearisome debates over how sanctuary seats should be arranged and allocated lie fundamental disagreements over the kinds of social and religious values that the synagogue should project and the relationship between the synagogue and the larger society that surrounds it. As we shall see, where people sit reveals much about what they believe. The necessarily limited study of seating patterns that follows focuses only on the most important and controversial seating innovation in the American synagogue: mixed (family) seating. Other innovations - seats that no longer face east, 3 pulpits moved from center to front, 4 free (un assigned) seating, closed-off pew ends, and the like - require separate treatment. As we shall see, mixed seating is a ramified and multifaceted issue that clearly reflects the impact of American values on synagogue life, for it pits family unity, sexual equality, and modernity against the accepted Jewish legal (halachic) practice of sexual separatiop in prayer. -

A Synagogue for All Families: Interfaith Inclusion in Conservative Synagogues

A Synagogue for All Families Interfaith Inclusion in Conservative Synagogues Introduction Across North America, Conservative kehillot (synagogues) create programs, policies, and welcoming statements to be inclusive of interfaith families and to model what it means for 21st century synagogues to serve 21 century families. While much work remains, many professionals and lay leaders in Conservative synagogues are leading the charge to ensure that their community reflects the prophet Isaiah’s vision that God’s house “shall be a house of prayer for all people” (56:7). In order to share these congregational exemplars with other leaders who want to raise the bar for inclusion of interfaith families in Conservative Judaism, the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism (USCJ) and InterfaithFamily (IFF) collaborated to create this Interfaith Inclusion Resource for Conservative Synagogues. This is not an exhaustive list, but a starting point. This document highlights 10 examples where Conservative synagogues of varying sizes and locations model inclusivity in marketing, governance, pastoral counseling and other key areas of congregational life. Our hope is that all congregations will be inspired to think as creatively as possible to embrace congregants where they are, and encourage meaningful engagement in the synagogue and the Jewish community. We are optimistic that this may help some synagogues that have not yet begun the essential work of the inclusion of interfaith families to find a starting point that works for them. Different synagogues may be in different places along the spectrum of welcoming and inclusion. Likewise, the examples presented here reflect a spectrum, from beginning steps to deeper levels of commitment, and may evolve as synagogues continue to engage their congregants in interfaith families. -

Download Ji Calendar Educator Guide

xxx Contents The Jewish Day ............................................................................................................................... 6 A. What is a day? ..................................................................................................................... 6 B. Jewish Days As ‘Natural’ Days ........................................................................................... 7 C. When does a Jewish day start and end? ........................................................................... 8 D. The values we can learn from the Jewish day ................................................................... 9 Appendix: Additional Information About the Jewish Day ..................................................... 10 The Jewish Week .......................................................................................................................... 13 A. An Accompaniment to Shabbat ....................................................................................... 13 B. The Days of the Week are all Connected to Shabbat ...................................................... 14 C. The Days of the Week are all Connected to the First Week of Creation ........................ 17 D. The Structure of the Jewish Week .................................................................................... 18 E. Deeper Lessons About the Jewish Week ......................................................................... 18 F. Did You Know? ................................................................................................................. -

Some Highlights of the Mossad Harav Kook Sale of 2017

Some Highlights of the Mossad HaRav Kook Sale of 2017 Some Highlights of the Mossad HaRav Kook Sale of 2017 By Eliezer Brodt For over thirty years, starting on Isru Chag of Pesach, Mossad HaRav Kook publishing house has made a big sale on all of their publications, dropping prices considerably (some books are marked as low as 65% off). Each year they print around twenty new titles. They also reprint some of their older, out of print titles. Some years important works are printed; others not as much. This year they have printed some valuable works, as they did last year. See here and here for a review of previous year’s titles. If you’re interested in a PDF of their complete catalog, email me at [email protected] As in previous years, I am offering a service, for a small fee, to help one purchase seforim from this sale. The sale’s last day is Tuesday. For more information about this, email me at Eliezerbrodt-at-gmail.com. Part of the proceeds will be going to support the efforts of the Seforim Blog. What follows is a list and brief description of some of their newest titles. 1. הלכות פסוקות השלם,ב’ כרכים, על פי כת”י ששון עם מקבילות מקורות הערות ושינויי נוסחאות, מהדיר: יהונתן עץ חיים. This is a critical edition of this Geonic work. A few years back, the editor, Yonason Etz Chaim put out a volume of the Geniza fragments of this work (also printed by Mossad HaRav Kook). 2. ביאור הגר”א ,לנ”ך שיר השירים, ב, ע”י רבי דוד כהן ור’ משה רביץ This is the long-awaited volume two of the Gr”a on Shir Hashirim, heavily annotated by R’ Dovid Cohen. -

A USER's MANUAL Part 1: How Is Halakhah Organized?

TORAHLEADERSHIP.ORG RABBI ARYEH KLAPPER HALAKHAH: A USER’S MANUAL Part 1: How is Halakhah Organized? I. How is Halakhah Organized? 4 case studies a. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1, and gemara thereupon b. Support of the poor Peiah, Bava Batra, Matnot Aniyyim, Yoreh Deah) c. Conversion ?, Yevamot, Issurei Biah, Yoreh Deah) d. Mourning Moed Qattan, Shoftim, Yoreh Deiah) Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 From what time may one recite the Shema in the evening? From the hour that the kohanim enter to eat their terumah Until the end of the first watch, in the opinion of Rabbi Eliezer. The Sages say: Until midnight. Rabban Gamliel says: Until morning. It happened that his sons came from a wedding feast. They said to him: We have not yet recited the Shema. He said to them: If it has not yet morned, you are obligated to recite it. Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 2a What is the context of the Mishnah’s opening “From when”? Also, why does it teach about the evening first, rather than about the morning? The context is Scripture saying “when you lie down and when you arise” (Devarim 6:7, 11:9). what the Mishnah intends is: “The time of the Shema of lying-down – when is it?” Alternatively: The context is Creation, as Scripture writes “There was evening and there was morning”. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 (continued) Not only this – rather, everything about which the Sages say until midnight – their mitzvah is until morning. The burning of fats and organs – their mitzvah is until morning. All sacrifices that must be eaten in a day – their mitzvah is until morning. -

The Talmud in Tractate Rosh Hashana, Based on Expositions of The

yom kippur 5774 The Talmud in Tractate Rosh Hashana, based on expositions of the relevant verses, teaches us that there is an affirmative Mitzvah to eat and drink on the day prior to Yom Kippur until sunset, when the fast and the restrictions of the day begin. Indeed, the Talmud tells us that the reward for this feasting is equivalent to the reward for fasting on Yom Kippur itself. While it certainly is a wise practice for one who is about to commence a fast to fortify himself with food and drink, why does the Torah make it a special Mitzvah to do so? And why the great reward? Rabbi Yonah in his epic Mussar (Ethics) classic, Sharei Teshuva (4:8,9,10), provides a few reasons for this Mitzvah, two of which provide a particularly meaningful understanding of the Holiday. First, the feast before the fast recognizes the great opportunity Yom Kippur affords us to cleanse ourselves and draw ever closer to G-d. We effect a new reality for ourselves on Yom Kippur, one that anticipates and compels spiritual elevation. The feast before Yom Kippur is a celebration of this new reality and testifies to one’s longing to attain this additional intimacy. Second, it is critical that our inspirations not dissipate nor our commitments go unrealized. We need to conceive of strategies so that we do not fall prey as we have in the past and we must devise ways to ensure that our newly-inspired spiritual resolutions are actualized. This of course requires mental and physical energy. -

Yom Kippur Yizkor – out of Time – 9.28.20

Drasha – Yom Kippur Yizkor – Out of Time – 9.28.20 One of the details we’ve had to contend with as we work on coming back to synagogue is the signage. We want to make sure that, as different as things are, everyone knows where to go and where not to go, what to do and what not to do. We have signs with arrows pointing us in the right direction, we have signs with rules about COVID safety protocols, and we have signs telling not to go beyond this point. The Torah has a similar sign in the form of a verse in the Book of Leviticus. It says (Vayikra 16:2) V’Al Yavo B’Chol Eit El HaKodesh – And don’t come at any time into the [Inner] Sanctum. Rabbi Shlomo Ephraim Luntschitz, author of the biblical commentary Kli Yakar, explains the verse as saying that the Kohen Gadol (High Priest) couldn’t go to the Kodesh Kadoshim (Temple Inner Sanctum) on any day of the year related to time. He was only allowed to go there on the day of the year that is beyond time, which is Yom Kippur. Time is a creation. This is the reason time has limitations, such as before and after. There is one day a year that is above time: Yom Kippur. On this day, we don’t eat or drink; we become like angels, heavenly beings, beyond the boundaries of the physical world. The Kodesh Kadoshim itself was beyond time and space. As the Talmud (Megillah 10b) says “We received the tradition from our forefathers: The Ark of the Covenant didn't take up any room." The Kohen Gadol went to this heavenly place on Yom Kippur because they are both beyond the boundaries of this world. -

Teacher's Guide & Student Worksheets

Teacher's Guide & Student Worksheets An interdisciplinary curriculum that weaves together Jewish tradition and contemporary food issues www.hazon.org/jfen Hazon works to create healthy and sustainable communities in the Jewish world and beyond. Teachers Guide and Student Worksheets www.hazon.org/jfen Authors: Judith Belasco, Lisa Sjostrom Contributing Author: Ronit Ziv-Zeiger, Jenna Levy Design Work: Avigail Hurvitz-Prinz, Lisa Kaplan, Rachel Chetrit Curriculum Advisors: Mick Fine, Rachel Jacoby Rosenfield, Elisheva Urbas, Molly Weingrod, David Franklin, Natasha Aronson Educational Partnerships & Outreach Advisor: Elena Sigman Min Ha’Aretz Advisory Board: Judith Belasco, Cheryl Cook, Rachel Rosenfield, Nigel Savage, Elena Sigman, Elisheva Urbas, Molly Weingrod Special thanks to: Gayle Adler and educators at Beit Rabban, Mick Fine, Benjamin Mann, & Dr. Steven Lorch at Solomon Schechter School of Manhattan for their extensive work to develop the Min Ha’Aretz curriculum Hazon Min Ha’Aretz Family Education Initiative Staff Judith Belasco, Director of Food Programs, [email protected] Daniel Infeld, Food Progams Fellow, [email protected] Hazon | 125 Maiden Lane, New York, NY 10038 | 212 644 2332 | fax: 212 868 7933 www.hazon.org | www.jcarrot.org – “Best New Blog” in the 2007 Jewish & Israeli Blog Awards Copyright © 2010 by Hazon. All rights reserved. Hazon works to create healthy and sustainable communities in the Jewish world and beyond. “The Torah is a commentary on the world, and the world is a commentary on the Torah…” Cover photos courtesy -

Daf Ditty Pesachim 78: Korban Pesach Today (?)

Daf Ditty Pesachim 78: Korban Pesach today (?) Three girls in Israel were detained by the Israeli Police (2018). The girls are activists of the “Return to the Mount” (Chozrim Lahar) movement. Why were they detained? They had posted Arabic signs in the Muslim Quarter calling upon Muslims to leave the Temple Mount area until Friday night, in order to allow Jews to bring the Korban Pesach. This is the fourth time that activists of the movement will come to the Old City on Erev Pesach with goats that they plan to bring as the Korban Pesach. There is also an organization called the Temple Institute that actively is trying to bring back the Korban Pesach. It is, of course, very controversial and the issues lie at the heart of one of the most fascinating halachic debates in the past two centuries. 1 The previous mishnah was concerned with the offering of the paschal lamb when the people who were to slaughter it and/or eat it were in a state of ritual impurity. Our present mishnah is concerned with a paschal lamb which itself becomes ritually impure. Such a lamb may not be eaten. (However, we learned incidentally in our study of 5:3 that the blood that gushed from the lamb's throat at the moment of slaughter was collected in a bowl by an attendant priest and passed down the line so that it could be sprinkled on the altar). Our mishnah states that if the carcass became ritually defiled, even if the internal organs that were to be burned on the altar were intact and usable the animal was an invalid sacrifice, it could not be served at the Seder and the blood should not be sprinkled. -

How to Run a Passover Seder

How to Run a Passover Seder Rabbi Josh Berkenwald – Congregation Sinai We Will Cover: ´ Materials Needed ´ Haggadah ´ Setting up the Seder Plate ´ What do I have to do for my Seder to be “kosher?” ´ Music at the Seder ´ Where can I find more resources? Materials Needed – For the Table ü A Table and Tablecloth ü Seder Plate if you don’t have one, make your own. All you need is a plate. ü Chairs – 1 per guest ü Pillows / Cushions – 1 per guest ü Candles – 2 ü Kiddush Cup / Wine Glass – 1 per guest Don’t forget Elijah ü Plate / Basket for Matzah ü Matzah Cover – 3 Compartments ü Afikomen Bag ü Decorations Flowers, Original Art, Costumes, Wall Hangings, etc., Be Creative Materials Needed - Food ü Matzah ü Wine / Grape Juice ü Karpas – Leafy Green Vegetable Parsely, Celery, Potato ü Salt Water ü Maror – Bitter Herb Horseradish, Romaine Lettuce, Endive ü Charoset Here is a link to four different recipes ü Main Course – Up to you Gefilte Fish, Hard Boiled Eggs, Matzah Ball Soup Haggadah If you need them, order quickly – time is running out Lots of Options A Different Night; A Night to Remember https://www.haggadahsrus.com Make Your Own – Print at Home https://www.haggadot.com Sefaria All English - Jewish Federations of North America For Kids – Punktorah Setting Up the Seder Plate Setting Up the Matzah Plate 3 Sections Conducting the Seder 15 Steps of the Seder Kadesh Maror Urchatz Korech Karpas Shulchan Orech Yachatz Tzafun Magid Barech Rachtza Hallel Motzi Nirtza Matza Conducting the Seder 15 Steps of the Seder *Kadesh Recite the Kiddush *Urchatz Wash hands without a blessing *Karpas Eat parsley or potato dipped in salt water *Yachatz Break the middle Matza. -

EREV PESACH WHICH OCCURS on SHABBOS: a Practical Guide

Rabbi Aaron Kraft Dayan EREV PESACH WHICH OCCURS ON SHABBOS: A Practical Guide When Erev Pesach coincides with Shabbos, we benefit from Friday (13th of Nisan; this year, March 26, 2021) or Shabbos having a restful and spiritually uplifting day leading into the (Erev Pesach; this year, March 27, 2021)? The Shulchan Aruch Seder night. However, this infrequent calendrical occurrence (ibid.) says to burn most of the chametz on Friday, leaving some also raises practical questions relating to the halachos of Erev for the Shabbos meals (see next section). Whatever chametz Pesach1 as well as to the proper fulfilment of the mitzvos of remains after the meals should be broken into small crumbs Shabbos. This article will address these concerns. and disposed of in a manner that destroys it completely but does not violate the laws of Shabbos. Preferred methods include flushing the crumbs down the toilet, feeding them to TAANIS BECHOROS a pet, or throwing them into a garbage outside of the house. While on a regular Erev Pesach, firstborn males customarily Larger quantities may also be given to a non-Jew (but you fast, fasting is prohibited on Shabbos either because it detracts should not directly ask the non-Jew to remove more than from the mitzvah of oneg Shabbos or because an obligation to a meal’s worth of chametz from your house – see Shulchan eat three meals exists (OC 288:1 and Beur Halacha). Therefore, Aruch 444:4 and Mishna Berura 444:18-20). the Beis Yosef (OC 470) cites opposing positions whether to According to the Shulchan Aruch (OC 444:2), the burning observe the taanis on Thursday or not at all this year. -

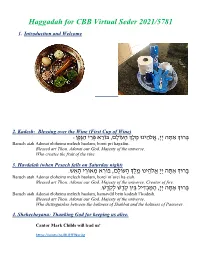

Haggadah for CBB Virtual Seder 2021/5781

Haggadah for CBB Virtual Seder 2021/5781 1. Introduction and Welcome 2. Kadesh: Blessing over the Wine (First Cup of Wine) ָבּרוּ�ַאָתּה ְיָיֱ, א�ֵהינֶוּ מֶל� ָהעָוֹלם, בּוֵֹראְפִּרי ַהָגֶּפן : Baruch atah Adonai eloheinu melech haolam, borei pri hagafen. Blessed art Thou, Adonai our God, Majesty of the universe, Who creates the fruit of the vine. 3. Havdalah (when Pesach falls on Saturday night) ָבּרוַּ� אָתּה ְיָיֱא� ֵֽהינ ֶֽוּ מֶל� ָהעָוֹלם, בּוֵֹראְמאוֵֹרי ָהֵאשׁ . Baruch atah Adonai eloheinu melech haolam, borei m’orei ha-eish. Blessed art Thou, Adonai our God, Majesty of the universe, Creator of fire. ָבּרוַּ� אָתּה ְיָי, ַהַמְּבִדּיל ֵבּי ֹֽן קֶדשְׁל ֹֽקֶדשׁ . Baruch atah Adonai eloheinu melech haolam, hamavdil bein kodesh l’kodesh. Blessed art Thou, Adonai our God, Majesty of the universe, Who distinguishes between the holiness of Shabbat and the holiness of Passover. 4. Shehecheyanu: Thanking God for keeping us alive. Cantor Mark Childs will lead us! https://youtu.be/RUEfFfNxcUg 5. Urchatz: First washing (no blessing) from the 1771 First Edition of Encyclopedia Britannica: What did the non-Jewish editors (Edinburgh, Scotland 1768-1771) know about Jews? We wash our hands! 6. Karpas: Celebrating Springtime בָּרוּ� אַתָּ ה יְיָ, אֱ �הֵ ינוּ מֶ לֶ� הָ עוֹלָם, בּוֹרֵ א פְּרִ י הָ אֲ דָ מָ ה : Baruch atah Adonai eloheinu melech haolam borei pri ha-adamah. Blessed art Thou, Adonai our God, Majesty of the universe, Who creates the fruit of the earth. Springtime in Santa Barbara: This is happening here, now! 7. Yachatz: Silently Breaking the Middle Matzah and Hiding One Half 8. Ha Lachma Anya: This is the Bread of Poverty This is the bread of poverty which our ancestors ate in the land of Egypt.