Therapeutic Class Overview Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treatment of Social Phobia with Antidepressants

Antidepressants for Social Phobia Treatment of Social Phobia With Antidepressants Franklin R. Schneier, M.D. This article reviews evidence for the utility of antidepressant medications in the treatment of social phobia. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) were the first antidepressants shown to be effective © Copyrightfor social phobia, but 2001dietary restrictions Physicians and a relatively Postgraduate high rate of adverse effects Press, often relegate Inc. MAOIs to use after other treatments have been found ineffective. Reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase (RIMAs) hold promise as safer alternatives to MAOIs, but RIMAs may be less effective and are currently unavailable in the United States. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), of which paroxetine has been the best studied in social phobia to date, have recently emerged as a first- line treatment for the generalized subtype of social phobia. The SSRIs are well tolerated and consis- tently have been shown to be efficacious in controlled trials. (J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62[suppl 1]:43–48) arly evidence that antidepressantsOne might personal have utility copy maypressant be printed treatment of other anxiety disorders, such as panic E in the treatment of social phobia emerged in the disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. In particular, 1970s when studies found efficacy for monoamine oxidase the high rate of comorbidity of anxiety disorders with de- inhibitors (MAOIs) in patient samples that included both pression3 makes treatment with antidepressants an efficient -

Guideline for the Treatment of Breakthrough and the Prevention of Refractory Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting in Children with Cancer

This is a repository copy of Guideline for the Treatment of Breakthrough and the Prevention of Refractory Chemotherapy-induced Nausea and Vomiting in Children with Cancer. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/97043/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Flank, Jaqueline, Robinson, Paula, Holdsworth, Mark et al. (7 more authors) (2016) Guideline for the Treatment of Breakthrough and the Prevention of Refractory Chemotherapy-induced Nausea and Vomiting in Children with Cancer. Pediatric blood & cancer. ISSN 1545-5009 https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.25955 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Pediatric Blood & Cancer Guideline for the Treatment of Breakthrough and the Prevention of Refractory Chemotherapy-induced Nausea and Vomiting in Children with Cancer Journal: Pediatric Blood & Cancer Manuscript ID PBC-15-1233.R1 Wiley - ManuscriptFor -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0024365A1 Vaya Et Al

US 2006.0024.365A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0024365A1 Vaya et al. (43) Pub. Date: Feb. 2, 2006 (54) NOVEL DOSAGE FORM (30) Foreign Application Priority Data (76) Inventors: Navin Vaya, Gujarat (IN); Rajesh Aug. 5, 2002 (IN)................................. 699/MUM/2002 Singh Karan, Gujarat (IN); Sunil Aug. 5, 2002 (IN). ... 697/MUM/2002 Sadanand, Gujarat (IN); Vinod Kumar Jan. 22, 2003 (IN)................................... 80/MUM/2003 Gupta, Gujarat (IN) Jan. 22, 2003 (IN)................................... 82/MUM/2003 Correspondence Address: Publication Classification HEDMAN & COSTIGAN P.C. (51) Int. Cl. 1185 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS A6IK 9/22 (2006.01) NEW YORK, NY 10036 (US) (52) U.S. Cl. .............................................................. 424/468 (22) Filed: May 19, 2005 A dosage form comprising of a high dose, high Solubility active ingredient as modified release and a low dose active ingredient as immediate release where the weight ratio of Related U.S. Application Data immediate release active ingredient and modified release active ingredient is from 1:10 to 1:15000 and the weight of (63) Continuation-in-part of application No. 10/630,446, modified release active ingredient per unit is from 500 mg to filed on Jul. 29, 2003. 1500 mg, a process for preparing the dosage form. Patent Application Publication Feb. 2, 2006 Sheet 1 of 10 US 2006/0024.365A1 FIGURE 1 FIGURE 2 FIGURE 3 Patent Application Publication Feb. 2, 2006 Sheet 2 of 10 US 2006/0024.365A1 FIGURE 4 (a) 7 FIGURE 4 (b) Patent Application Publication Feb. 2, 2006 Sheet 3 of 10 US 2006/0024.365 A1 FIGURE 5 100 ov -- 60 40 20 C 2 4. -

Insights Into the Mechanisms of Action Ofthe MAO Inhibitors Phenelzine and Tranylcypromine

Insights into the Mechanisms of Action of the MAO Inhibitors Phenelzine and Tranylcypromine: A Review Glen B. Baker, Ph.D., Ronald T. Coutts, Ph.D., D.Sc., Kevin F. McKenna, M.D., and Rhonda L. Sherry-McKenna, B.Sc. Neurochemical Research Unit, Department of Psychiatry and Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta Submitted: July 10, 1992 Accepted: October 7, 1992 Although the non-selective monoamine oxidase inhibitors phenelzine and tranylcypromine have been used for many years, much still remains to be understood about their mechanisms of action. Other factors, in addition to the inhibition of monoamine oxidase and the subsequent elevation of brain levels of the catecholamines and 5-hydroxytryptamine, may contribute to the overall pharma- cological profiles ofthese drugs. This review also considers the effects on brain levels of amino acids and trace amines, uptake and release of neurotransmitter amines at nerve terminals, receptors for amino acids and amines, and enzymes other than monoamine oxidase, including enzymes involved in metabolism of other drugs. The possible contributions of metabolism and stereochemistry to the actions of these monoamine oxidase inhibitors are discussed. Key Words: amino acids, monoamine oxidase, neurotransmitter amines, phenelzine, tranylcypromine, uptake Despite the fact that the non-selective monoamine oxidase nerve endings (Baker et al 1977; Raiteri et al 1977) and/or (MAO) inhibitors phenelzine (PLZ) and tranylcypromine may act as neuromodulators through direct actions on recep- (TCP) (see Fig. 1) have been used clinically for many years, tors for the catecholamines and/or 5-HT (Jones 1983; much remains to be learned about theirmechanisms ofaction. -

Blood Thinners These Medications Require up to 2 Weeks of Discontinued Use Prior to a Myelogram Procedure

MEDICATIONS TO AVOID PRE & POST MYELOGRAMS Radiocontrast agents used in myelography have the ability to lower the seizure threshold and when used with other drugs that also have this ability, may lead to convulsions. Drugs that possess the ability to lower seizure threshold should be discontinued at least 48 hours prior to myelography if possible and should not be resumed until at least 24 hours post-procedure. Drugs are listed below. ***Always consult with your prescribing physician prior to stoppage of your medication. Phenothiazines Antidepressants MAO Inhibitors Acetophenazine (Tindal) Amitriptyline (Elavil) Furazolidone (Furoxone) Chlorpromazine (Thorazine) Amoxapine (Asendin) Isocarboxazid (Marplan) Promethazine (Phenergan) Bupropion *(Welbutrin, Zyban) Pargyline (Eutonyl) Ethopropazine (Parsidol) Clomipramine (Anafranil, Placil) Phenelzine (Nardil) Fluphenazine (Prolixin) Desipramine (Norapramin) Procarbazine (Matulane) Mesoridazine (Serentil) Doxepin (Sinequan) Tranlcypromine (Parnate) Methdilazine (Tacaryl) Imipramine (Tofranil) Perphenazine (Trilafon) Maprotiline (Ludiomil) CNS Stimulants Proclorperazine (Compazine) Nortriptyline (Pamelor) Amphetamines Promazine (Sparine) Protriptyline (Vivactil) Pemoline (Cylert) Promethazine (Phenergan) Trimipramine (Surmontil) Thiethylperazine (Torecan) Thioridazine (Mellaril) Combination Antidepressants Trifluoperazine (Stelazine) Amitriptyline + Chlordiazepoxide (Limbitrol DS) Triflupromazine (Vesprin) Amitriptyline + Perphenazine (Triavil) Largon Levoprome Miscellaneous Antipsychotics -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2015/0011643 A1 Dilisa Et Al

US 2015 0011643A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2015/0011643 A1 DiLisa et al. (43) Pub. Date: Jan. 8, 2015 (54) TREATMENT OF HEART FAILURE AND (60) Provisional application No. 61/038,230, filed on Mar. ASSOCATED CONDITIONS BY 20, 2008, provisional application No. 61/155,704, ADMINISTRATION OF MONOAMINE filed on Feb. 26, 2009. OXIDASE INHIBITORS (71) Applicants:Nazareno Paolocci, Baltimore, MD Publication Classification (US); Univeristy of Padua, Padova (IT) (51) Int. Cl. (72) Inventors: Fabio DiLisa, Padova (IT): Ning Feng, A63L/38 (2006.01) Baltimore, MD (US); Nina Kaludercic, (52) U.S. Cl. Baltimore, MD (US); Nazareno CPC ..... ... A61 K31/138 (2013.01) Paolocci, Baltimore, MD (US) USPC .......................................................... S14/651 (21) Appl. No.: 14/332,234 (22) Filed: Jul. 15, 2014 (57) ABSTRACT Related U.S. Application Data Administration of monoamine oxidase inhibitors is useful in (63) Continuation of application No. 12/407,739, filed on the prevention and treatment of heart failure and incipient Mar. 19, 2009, now abandoned. heart failure. Patent Application Publication Jan. 8, 2015 Sheet 1 of 2 US 201S/0011643 A1 Figure 1 Sial 8. Sws-L) Cleaved Š Caspase-3 ) Figure . Prevention of caspase-3 productief) fron cardiomyocytes Lapoi) reatment with clorgyi Be. Patent Application Publication Jan. 8, 2015 Sheet 2 of 2 US 201S/0011643 A1 Figure 2 8:38:8 ::::::::8: US 2015/0011643 A1 Jan. 8, 2015 TREATMENT OF HEART FAILURE AND in the art is a variety of MAO inhibitors and their pharmaceu ASSOCATED CONDITIONS BY tically acceptable compositions for administration, in accor ADMINISTRATION OF MONOAMINE dance with the present invention, to mammals including, but OXIDASE INHIBITORS not limited to, humans. -

Pharmaceutical Appendix to the Tariff Schedule 2

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2007) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2007) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 2 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. ABACAVIR 136470-78-5 ACIDUM LIDADRONICUM 63132-38-7 ABAFUNGIN 129639-79-8 ACIDUM SALCAPROZICUM 183990-46-7 ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACIDUM SALCLOBUZICUM 387825-03-8 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ACIFRAN 72420-38-3 ABAPERIDONUM 183849-43-6 ACIPIMOX 51037-30-0 ABARELIX 183552-38-7 ACITAZANOLAST 114607-46-4 ABATACEPTUM 332348-12-6 ACITEMATE 101197-99-3 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ACITRETIN 55079-83-9 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ACIVICIN 42228-92-2 ABETIMUSUM 167362-48-3 ACLANTATE 39633-62-0 ABIRATERONE 154229-19-3 ACLARUBICIN 57576-44-0 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ACLATONIUM NAPADISILATE 55077-30-0 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ACODAZOLE 79152-85-5 ABRINEURINUM 178535-93-8 ACOLBIFENUM 182167-02-8 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ACONIAZIDE 13410-86-1 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ACOTIAMIDUM 185106-16-5 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 -

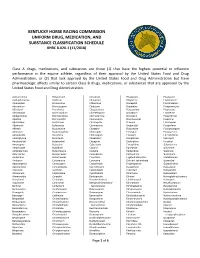

Drug and Medication Classification Schedule

KENTUCKY HORSE RACING COMMISSION UNIFORM DRUG, MEDICATION, AND SUBSTANCE CLASSIFICATION SCHEDULE KHRC 8-020-1 (11/2018) Class A drugs, medications, and substances are those (1) that have the highest potential to influence performance in the equine athlete, regardless of their approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration, or (2) that lack approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration but have pharmacologic effects similar to certain Class B drugs, medications, or substances that are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Acecarbromal Bolasterone Cimaterol Divalproex Fluanisone Acetophenazine Boldione Citalopram Dixyrazine Fludiazepam Adinazolam Brimondine Cllibucaine Donepezil Flunitrazepam Alcuronium Bromazepam Clobazam Dopamine Fluopromazine Alfentanil Bromfenac Clocapramine Doxacurium Fluoresone Almotriptan Bromisovalum Clomethiazole Doxapram Fluoxetine Alphaprodine Bromocriptine Clomipramine Doxazosin Flupenthixol Alpidem Bromperidol Clonazepam Doxefazepam Flupirtine Alprazolam Brotizolam Clorazepate Doxepin Flurazepam Alprenolol Bufexamac Clormecaine Droperidol Fluspirilene Althesin Bupivacaine Clostebol Duloxetine Flutoprazepam Aminorex Buprenorphine Clothiapine Eletriptan Fluvoxamine Amisulpride Buspirone Clotiazepam Enalapril Formebolone Amitriptyline Bupropion Cloxazolam Enciprazine Fosinopril Amobarbital Butabartital Clozapine Endorphins Furzabol Amoxapine Butacaine Cobratoxin Enkephalins Galantamine Amperozide Butalbital Cocaine Ephedrine Gallamine Amphetamine Butanilicaine Codeine -

BMJ Open Is Committed to Open Peer Review. As Part of This Commitment We Make the Peer Review History of Every Article We Publish Publicly Available

BMJ Open is committed to open peer review. As part of this commitment we make the peer review history of every article we publish publicly available. When an article is published we post the peer reviewers’ comments and the authors’ responses online. We also post the versions of the paper that were used during peer review. These are the versions that the peer review comments apply to. The versions of the paper that follow are the versions that were submitted during the peer review process. They are not the versions of record or the final published versions. They should not be cited or distributed as the published version of this manuscript. BMJ Open is an open access journal and the full, final, typeset and author-corrected version of record of the manuscript is available on our site with no access controls, subscription charges or pay-per-view fees (http://bmjopen.bmj.com). If you have any questions on BMJ Open’s open peer review process please email [email protected] BMJ Open Pediatric drug utilization in the Western Pacific region: Australia, Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong and Taiwan Journal: BMJ Open ManuscriptFor ID peerbmjopen-2019-032426 review only Article Type: Research Date Submitted by the 27-Jun-2019 Author: Complete List of Authors: Brauer, Ruth; University College London, Research Department of Practice and Policy, School of Pharmacy Wong, Ian; University College London, Research Department of Practice and Policy, School of Pharmacy; University of Hong Kong, Centre for Safe Medication Practice and Research, Department -

Ssris and Tricyclic Antidepressants Increase Response Rates in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in the Short Term

Evid Based Mental Health: first published as 10.1136/ebmh.4.2.54 on 1 May 2001. Downloaded from Review: SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants increase response rates in post-traumatic stress disorder in the short term Stein DJ, Zungu-Dirwayi N, van Der Linden GJ, et al. Pharmacotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(4):CD002795 (latest version 20 Jul 2000). QUESTION: In patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), is pharmacotherapy effective for relieving symptoms? Data sources Main results Studies were identified by searching Medline (1966–99); 13 RCTs (14 comparisons) of tricyclic antidepressants PsycLIT; the National PTSD Center Pilots database; (TCAs) (3 comparisons), monoamine oxidase Dissertation Abstracts; and the Cochrane Collaboration (MAO) inhibitors (2 comparisons), brofaromine Depression, Anxiety & Neurosis Controlled Trials Regis- (2 comparisons), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors ter; by scanning reference lists of articles; and by contact- (SSRIs) (4 comparisons), alprazolam (1 comparison), ing researchers and pharmaceutical companies. lamotrigine (1 comparison), and inositol (1 compari- son) met criteria. Follow up ranged from 4–14 weeks Study selection (mean 9 wks). More patients responded to SSRIs Source of funding: Published or unpublished randomised controlled trials MRC Research Unit on or TCAs than placebo (table). In 1 RCT, phenelzine led Anxiety and Stress (RCTs) in any language were selected if participants had to a higher response rate than placebo; 1 small RCT Disorders, Cape Town, PTSD (as defined by authors) and if a drug was of lamotrigine and 2 RCTs of brofaromine showed no South Africa. compared with placebo or another drug. difference in response rates between groups For correspondence: Data extraction (table). -

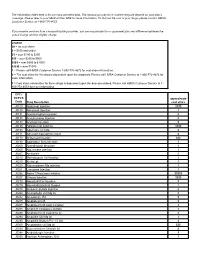

CPT / HCPCS Code Drug Description Approximate Cost Share

The information listed here is for our most prevalent plan. The amount you pay for a covered drug will depend on your plan’s coverage. Please refer to your Medical Plan GTB for more information. To find out the cost of your drugs, please contact HMSA Customer Service at 1-800-776-4672. If you receive services from a nonparticipating provider, you are responsible for a copayment plus any difference between the actual charge and the eligible charge. Legend $0 = no cost share $ = $100 and under $$ = over $100 to $250 $$$ = over $250 to $500 $$$$ = over $500 to $1000 $$$$$ = over $1000 1 = Please call HMSA Customer Service 1-800-776-4672 for cost share information. 2 = The cost share for this drug is dependent upon the diagnosis. Please call HMSA Customer Service at 1-800-772-4672 for more information. 3 = Cost share information for these drugs is dependent upon the dose prescribed. Please call HMSA Customer Service at 1- 800-772-4672 for more information. CPT / HCPCS approximate Code Drug Description cost share J0129 Abatacept Injection $$$$ J0130 Abciximab Injection 3 J0131 Acetaminophen Injection $ J0132 Acetylcysteine Injection $ J0133 Acyclovir Injection $ J0135 Adalimumab Injection $$$$ J0153 Adenosine Inj 1Mg $ J0171 Adrenalin Epinephrine Inject $ J0178 Aflibercept Injection $$$ J0180 Agalsidase Beta Injection 3 J0200 Alatrofloxacin Mesylate 3 J0205 Alglucerase Injection 3 J0207 Amifostine 3 J0210 Methyldopate Hcl Injection 3 J0215 Alefacept 3 J0220 Alglucosidase Alfa Injection 3 J0221 Lumizyme Injection 3 J0256 Alpha 1 Proteinase Inhibitor -

Mikocka-Walus Et Al-2017

This is a repository copy of Adjuvant therapy with antidepressants for the management of inflammatory bowel disease (Protocol). White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/118724/ Version: Published Version Article: Mikocka-Walus, Antonina Anna orcid.org/0000-0003-4864-3956, Fielder, Andrea, Prady, Stephanie Louise orcid.org/0000-0002-8933-8045 et al. (3 more authors) (2017) Adjuvant therapy with antidepressants for the management of inflammatory bowel disease (Protocol). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. ISSN 1469-493X https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012680 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Adjuvant therapy with antidepressants for the management of inflammatory bowel disease (Protocol) Mikocka-Walus A, Fielder A, Prady SL, Esterman AJ, Knowles S, Andrews JM Mikocka-Walus A, Fielder A, Prady SL, Esterman AJ, Knowles S, Andrews JM. Adjuvant therapy with antidepressants for the management of inflammatory bowel disease.