The SOS Pesca Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Highlights Situation Overview

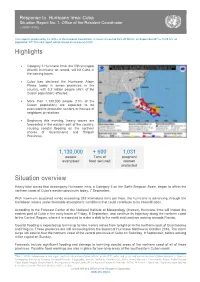

Response to Hurricane Irma: Cuba Situation Report No. 1. Office of the Resident Coordinator ( 07/09/ 20176) This report is produced by the Office of the Resident Coordinator. It covers the period from 20:00 hrs. on September 06th to 14:00 hrs. on September 07th.The next report will be issued on or around 08/09. Highlights Category 5 Hurricane Irma, the fifth strongest Atlantic hurricane on record, will hit Cuba in the coming hours. Cuba has declared the Hurricane Alarm Phase today in seven provinces in the country, with 5.2 million people (46% of the Cuban population) affected. More than 1,130,000 people (10% of the Cuban population) are expected to be evacuated to protection centers or houses of neighbors or relatives. Beginning this evening, heavy waves are forecasted in the eastern part of the country, causing coastal flooding on the northern shores of Guantánamo and Holguín Provinces. 1,130,000 + 600 1,031 people Tons of pregnant evacuated food secured women protected Situation overview Heavy tidal waves that accompany Hurricane Irma, a Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Scale, began to affect the northern coast of Cuba’s eastern provinces today, 7 September. With maximum sustained winds exceeding 252 kilometers (km) per hour, the hurricane is advancing through the Caribbean waters under favorable atmospheric conditions that could contribute to its intensification. According to the Forecast Center of the National Institute of Meteorology (Insmet), Hurricane Irma will impact the eastern part of Cuba in the early hours of Friday, 8 September, and continue its trajectory along the northern coast to the Central Region, where it is expected to make a shift to the north and continue moving towards Florida. -

Office of the Resident Coordinator in Cuba Subject

United Nations Office of the Resident Coordinator in Cuba From: Office of the Resident Coordinator in Cuba Subject: Situation Report No. 6 “Hurricane IKE”- September 16, 2008- 18:00 hrs. Situation: A report published today, September 16, by the official newspaper Granma with preliminary data on the damages caused by hurricanes GUSTAV and IKE asserts that they are estimated at 5 billion USD. The data provided below is a summary of official data. Pinar del Río Cienfuegos 25. Ciego de Ávila 38. Jesús Menéndez 1. Viñales 14. Aguada de Pasajeros 26. Baraguá Holguín 2. La palma 15. Cumanayagua Camagüey 39. Gibara 3. Consolación Villa Clara 27. Florida 40. Holguín 4. Bahía Honda 16. Santo Domingo 28. Camagüey 41. Rafael Freyre 5. Los palacios 17. Sagüa la grande 29. Minas 42. Banes 6. San Cristobal 18. Encrucijada 30. Nuevitas 43. Antilla 7. Candelaria 19. Manigaragua 31. Sibanicú 44. Mayarí 8. Isla de la Juventud Sancti Spíritus 32. Najasa 45. Moa Matanzas 20. Trinidad 33. Santa Cruz Guantánamo 9. Matanzas 21. Sancti Spíritus 34. Guáimaro 46. Baracoa 10. Unión de Reyes 22. La Sierpe Las Tunas 47. Maisí 11. Perico Ciego de Ávila 35. Manatí 12. Jagüey Grande 23. Managua 36. Las Tunas 13. Calimete 24. Venezuela 37. Puerto Padre Calle 18 No. 110, Miramar, La Habana, Cuba, Apdo 4138, Tel: (537) 204 1513, Fax (537) 204 1516, [email protected], www.onu.org.cu 1 Cash donations in support of the recovery efforts, can be made through the following bank account opened by the Government of Cuba: Account Number: 033473 Bank: Banco Financiero Internacional (BFI) Account Title: MINVEC Huracanes restauración de daños Measures adopted by the Government of Cuba: The High Command of Cuba’s Civil Defense announced that it will activate its centers in all of Cuba to direct the rehabilitation of vital services that have been disrupted by the impact of Hurricanes GUSTAV and IKE. -

Portfolio of Opportunities for Foreign Investment 2018 - 2019

PORTFOLIO OF OPPORTUNITIES FOR FOREIGN INVESTMENT 2018 - 2019 INCLUDES TERRITORIAL DISTRIBUTION MINISTERIO DEL COMERCIO EXTERIOR Y LA INVERSIÓN EXTRANJERA PORTFOLIO OF OPPORTUNITIES FOR FOREIGN INVESTMENT 2018-2019 X 13 CUBA: A PLACE TO INVEST 15 Advantages of Investing in Cuba 16 Foreign Investment in Cuba 16 Foreign Investment in Figures 17 General Foreign Investment Policy Principles 19 Foreign Investment with agricultural cooperatives as partners X 25 FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES BY SECTOR X27 STRATEGIC CORE PRODUCTIVE TRANSFORMATION AND INTERNATIONAL INSERTION 28 Mariel Special Development Zone X BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES IN ZED MARIEL X 55 STRATEGIC CORE INFRASTRUCTURE X57 STRATEGIC SECTORS 58 Construction Sector X FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY SPECIFICATIONS 70 Electrical Energy Sector 71 Oil X FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY SPECIFICATIONS 79 Renewable Energy Sources X FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY SPECIFICATIONS 86 Telecommunications, Information Technologies and Increased Connectivity Sector 90 Logistics Sector made up of Transportation, Storage and Efficient Commerce X245 OTHER SECTORS AND ACTIVITIES 91 Transportation Sector 246 Mining Sector X FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY SPECIFICATIONS X FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY SPECIFICATIONS 99 Efficient Commerce 286 Culture Sector X FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY SPECIFICATIONS X FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY SPECIFICATIONS 102 Logistics Sector made up of Water and Sanitary Networks and Installations 291 Actividad Audiovisual X FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY SPECIFICATIONS X -

Las Tunas Province 31 / POP 538,000

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd %Las Tunas Province 31 / POP 538,000 Includes ¨ Why Go? Las Tunas . 335 Most travelers say hello and goodbye to Las Tunas province Monte Cabaniguan . .. 341 in the time that it takes to drive across it on the Carretera Puerto Padre . 341 Central (one hour on a good day). But, hang on a sec! This so-laid-back-it’s-nearly-falling-over collection of leather- Punta Covarrubias . .. 342 skinned cowboys and poetry-spouting country singers is Playas La Herradura, known for its daredevil rodeos and Saturday night street La Llanita & parties where barnstorming entertainment is served up at Las Bocas . 343 the drop of a sombrero. Although historically associated with the Oriente, Las Tu- nas province shares many attributes with Camagüey in the west. The flat grassy fields of the interior are punctuated Best Bucolic with sugar mills and cattle ranches, while the eco beaches Escapes on the north coast remain wild and lightly touristed, at least by Varadero standards. ¨ Monte Cabaniguan (p341) In this low-key land of the understated and underrated, ¨ El Cornito (p337) accidental visitors can enjoy the small-town charms of the ¨ Playa La Herradura (p343) provincial capital, or head north to the old mill town Puerto Padre where serenity rules. Best Places When to Go to Stay ¨ The wettest months are June and October, with over ¨ Hotel Cadillac (p337) 160mm of average precipitation. July and August are the ¨ Mayra Busto Méndez hottest months. (p337) ¨ Las Tunas has many festivals for a small city; the best is the ¨ Roberto Lío Montes de Oca Jornada Cucalambeana in June. -

Powereliteofcuba.Pdf

POWER ELITE OF CUBA General of the Army Raúl Castro (86 years old) First Secretary of the Communist Party An intolerant Marxist-Leninist, Raúl Castro is a highly organized, cautious and clannish leader with an unwavering commitment to Communism, Russia, Iran and Venezuela. In March 1953, Raúl traveled to Vienna (four months before the “Moncada”) to attend the Moscow sponsored World Youth Conference. Afterwards, he went to Budapest, Prague and Bucharest. He liked what he saw. During this trip he established a long-lasting friendship with Nikolai Leonov, a KGB espionage officer that later turned out to be a useful link with the Kremlin. Raúl recalled that from that moment on “he was ready to die for the Communist cause.” Declassified KGB documents offer evidence that Fidel Castro “deliberately made a Marxist of Raul.” At 22, back in Cuba, Raúl joined the Cuban Communist Party Youth Branch (CCP). Latter while in Mexico for the “Granma” operation, Raúl struck up a close ideological friendship with Ernesto “Che” Guevara and forged a commitment to create a Marxist society in Cuba. In 1963, Raúl was the official link between Fidel and Nikita Khrushchev to deploy nuclear missiles in Cuba. At 86, he still remains strongly attached to his lifelong ideology. While he is healthy and running Cuba, individual rights and private property will be forbidden in the island. (A car and a house are the exceptions). There are reports stating that Raúl is having health issues. Commander of the Rebel Army José Machado Ventura (87 years old) Second Secretary of the Communist Party A medical doctor, Machado was appointed to the Politburo in 1975. -

Cop13 Prop. 24

CoP13 Prop. 24 CONSIDERATION OF PROPOSALS FOR AMENDMENT OF APPENDICES I AND II A. Proposal Transfer of the population of Crocodylus acutus of Cuba from Appendix I to Appendix II, in accordance with Resolution Conf. 9.24 (Rev. CoP12) Annex 4, paragraph B. 2 e) and Resolution Conf. 11.16. B. Proponent Republic of Cuba. C. Supporting statement 1. Taxonomy 1.1 Class: Reptilia 1.2 Order: Crocodylia 1.3 Family: Crocodylidae 1.4 Species: Crocodylus acutus, Cuvier, 1807 1.5 Scientific synonyms: Crocodylus americanus 1.6 Common names: English: American crocodile, Central American alligator, South American alligator French: Crocodile américain, Crocodile à museau pointu Spanish: Cocodrilo americano, caimán, Lagarto, Caimán de la costa, Cocodrilo prieto, Cocodrilo de río, Lagarto amarillo, Caimán de aguja, Lagarto real 1.7 Code numbers: A-306.002.001.001 2. Biological parameters 2.1 Distribution The American crocodile is one of the most widely distributed species in the New World. It is present in the South of the Florida peninsula in the United States of America, the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of the South of Mexico, Central America and the North of South America, as well as, the islands of Cuba, Jamaica and La Española (Thorbjarnarson 1991). The countries included in this distribution are: Belize, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, El Salvador, United States of America, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru, Dominican Republic and Venezuela (Figure 1). Through its extensive distribution the C. acutus is present in a wide diversity of humid habitats. The most frequent is the coastal habitat of brackish or salt waters, such as the estuary sections of rivers; coastal lagoons and mangroves swamp. -

Influence of Geographic and Meteorological Factors in Fire Generation in Las Tunas Province

ISSN: 1996–2452 RNPS: 2148 Revista Cubana de Ciencias Forestales. 2020; September-December 8(3): 519-534 Translated from the original in spanish Original article Influence of geographic and meteorological factors in fire generation in las Tunas province Influencia de factores meteorológicos en la generación de incendios en la provincia de las Tunas Influência de factores meteorológicos na geração de incêndios na província de las Tunas María de los Ángeles Zamora Fernández1* https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2302-7076 Julia Azanza Ricardo1 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9454-9226 1Universidad de La Habana. Instituto Superior de Tecnologías y Ciencias Aplicadas. Cuba. *Correspondence author: [email protected] Received: January 21th, 2020. Approved: August 5th, 2020. ABSTRACT Due to the repercussions of fires, it is necessary to know the territorial particularities that favor their emergence and dispersion. Because of its meteorological characteristics, Las Tunas is a vulnerable province to the occurrence of fires. For this reason, this study intends to relate the occurrence and magnitude of fires with the geographical and meteorological conditions of Las Tunas and Puerto Padre municipalities in Las Tunas province, Cuba, in the period 2008-2012. For this purpose, 249 fires were analyzed along with the behavior of meteorological variables. There were found differences among the municipalities regarding the occurrence of fires, the areas affected and the factors related to the spreading. For the case of small fires, it was verified the relationship between meteorological variables and the area affected by fires, although the correlation values were not high. The variables with greater influence, as it was expected, were those related to the moisture of the combustible materials the accumulated of precipitations at 15 and 20 days before each fire and the relative humidity. -

La Lucha Insurreccional (1952-1958) En Las Tunas

LA LUCHA INSURRECCIONAL (1952-1958) EN LAS TUNAS. SU REFLEJO EN LOS DOCUMENTOS HISTÓRICOS THE INSURRECTIONAL STRUGGLE (1952-1958) IN LAS TUNAS PROVINCE. ITS REFLECTS ON THE HISTORICAL DOCUMENTS Eduardo Garcés Fernández1 ([email protected]) María Antonia Ochoa Brito ([email protected]) RESUMEN El objetivo principal del trabajo es dar a conocer los hechos históricos de la época y cómo lo reflejaron los documentos históricos. No ha sido la intención escribir la historia completa del período. Se emplearon los métodos de estudio de los documentos históricos (fuentes escritas) y los testimonios (fuentes orales) para corroborar y verificar las informaciones. Se analizaron, cartas, partes y órdenes militares, telegramas e informes. Todo ello permitió elaborar una síntesis que recoge algunos hechos de la historia de Las Tunas de 1952-1958 enriquecida con documentos de la época. PALABRAS CLAVES: hechos históricos, lucha insurreccional, grupos armados, guerrilleros, rebeldes. ABSTRACT The main objective of that work consists on let knowing the historical facts of the epoch and how historical documents. Show them on. The author’s intention is not making the complete history of that period. Some study methods were used from the historical documents (written fountains), and from testimony (oral fountains) to corroborate and verify the information. It was necessary to study letters, orders and military reports, telegrams and information. It let the author elaborate a synthesis which compiles some facts from the history (from 1952 to 1958) in Las -

United Nations Office of the Resident Coordinator in Cuba From

United Nations Office of the Resident Coordinator in Cuba From: Office of the Resident Coordinator in Cuba Subject: Situation Report No. 2 “Hurricane Paloma”— 12 November 2008, 16:00 hrs. Situation: On 8-9 November 2008, Cuba was struck, in less than 10 weeks, by a third high-powered hurricane named PALOMA. On a tour of the affected areas, Raúl Castro Ruz, President of the Councils of State and Ministers of Cuba, provided specific information on the assessment of the damage caused by the hurricanes in this cyclone season, as reported in Granma newspaper today, 12 November 2008. • GUSTAV brought about losses in the order of CUC 1.919 billion (US$ 2.072 billion); • IKE caused damage valued at CUC 6.737 billion (US$ 7.275 billion); • This accounts for CUC 8.656 billion in losses (US$ 9.349 billion); • With the new damage caused by Hurricane Paloma, losses will be in the vicinity of US$ 10 billion. The most affected territories are engaged in the recovery phase. Measures adopted by the Government of Cuba: The Cuban authorities continue to take measures and actions as part of the recovery phase, the highlights being as follows: • Raúl Castro Ruz, President of the Councils of State and Ministers of Cuba, and other high-ranking authorities toured the most affected areas. • They facilitated the return of most evacuees to their places of origin. • They continued to provide temporary accommodation/housing and food to the people that have lost their homes. • They facilitated the activation of cleaning and rubble/garbage removal brigades. • They mobilized vehicles and specialized personnel from other non-affected provinces in order to restore the electricity service and telecommunications. -

United Nations Office of the Resident Coordinator in Cuba

United Nations Office of the Resident Coordinator in Cuba From: Office of the Resident Coordinator in Cuba Subject: Situation Report No. 1 “Hurricane IKE”- September 8, 2008- 14:00 hrs. Situation: Hurricane IKE penetrated in Cuba through its northeastern corner on the night of Sunday 7 September with 194 km/h winds registered at Velasco, Holguin; and 130 km/h at Moa, another Holguin township. As it struck Cuba’s northeastern coast, it carried winds of 195 km/h and higher gusts and a barometer of 945 mb. IKE strikes Cuba just one week alter another violent hurricane, GUSTAV wrecked havoc and spread destruction in Western Cuba, especially in the Special Municipality of the Isle of Youth and the province of Pinar del Rio. With IKE, hurricane winds and torrential rains were compounded by violent sea penetrations in Cuba’s Northeastern-most area. Enormous damages were caused by 6-meter high waves which penetrated almost one kilometer inland destroying everything on its path, including urban areas of the city of Baracoa. Hurricane winds downed thousands of trees, telephone and power posts and caused serious damages to housing and other buildings. Rains are torrential. At Palenque de Yateras, 138 mm were recorded in less than 24 hours. 1 The storm’s eye followed a westerly path and entered the Caribbean Sea at midmorning Monday, after attacking Camaguey Province with 209 km/h winds. At Puerto Padre, Las Tunas Province, a wind squall of 192 km/h was recorded this Monday morning. As it swirls westwards over the warm waters of the Caribbean Sea, IKE will probable gain further in organization and strength. -

WFP Cuba Country Brief Increase in External Transport Costs

WFP Cuba In Numbers Country Brief USD 0.9 million six months net funding June 2021 requirements 47,6 mt of food assistance distributed January 2020 18,235 people assisted 49% 51% Operational Updates • WFP continues to foster the implementation of the Pro-Act project -jointly with FAO- in seven Operational Context municipalities of Villa Clara province in closed coordination with local and national counterparts. By the end of June, WFP facilitated a workshop to Over the last 50 years, Cuba's comprehensive social protection promote synergies and enhance coordination programmes have primarily eradicated poverty and hunger. between Pro-Act and seven projects which are Although effective, these programmes mostly rely on food being implemented in Villa Clara province also imports and strain the national budget. Recurrent natural focused on the resilience of local food systems to shocks place further challenges to food security and nutrition. disasters and climate change. About 25 people participated in this workshop including project WFP accompanies the Government on its efforts to develop a coordinators, local representatives of the new management model to make food-based social protection ministries of Agriculture, Environment, Higher programmes more efficient and sustainable. WFP supports Education as well as representatives of FAO, social safety nets for different vulnerable groups, strengthens UNDP, and European Union. agricultural value chains and promotes the improvement of resilience and disaster risk management. These activities • WFP is developing a pilot project that promotes contribute to Sustainable Goals 2, 5 and 17. preventive and parametric insurance approaches in two municipalities of the eastern provinces, WFP has been working with Cuba since 1963. -

Disaster Preparedness

SAVING LIVES CHANGING LIVES Cuba Annual Country Report 2019 Country Strategic Plan 2018 - 2019 Table of contents Summary 3 Context and Operations 6 CSP financial overview 8 Programme Performance 9 Strategic outcome 01 9 Strategic outcome 02 9 Strategic outcome 03 10 Strategic outcome 04 12 Strategic outcome 05 13 Cross-cutting Results 15 Progress towards gender equality 15 Protection 15 Accountability to affected populations 15 Environment 16 Disaster Preparedness 17 Data Notes 17 Figures and Indicators 19 WFP contribution to SDGs 19 Beneficiaries by Age Group 20 Beneficiaries by Residence Status 20 Annual Food Transfer 20 Strategic Outcome and Output Results 22 Cross-cutting Indicators 28 Cuba | Annual Country Report 2019 2 Summary Throughout 2019, the World Food Programme (WFP) continued supporting the Government’s social protection systems to improve food security and nutrition among beneficiaries by providing food and technical assistance. WFP contributed to systematize the results of the Nutritional Education Strategy led by the Ministry of Education in 34 municipalities, scaling up to include additional municipalities, beyond those supported. For the first time, WFP accompanied a pilot project to develop a nutrition behavioural-change strategy to prevent micronutrient deficiencies in Santiago de Cuba province, which has the highest anaemia prevalence in children aged 6-23 months. WFP advanced in strengthening food value chains to ensure stable food supply to social safety nets. WFP also supported the beans value chains in 18 selected municipalities from Pinar del Río, Matanzas, and the five eastern provinces, by completing the planned distribution of agricultural equipment and tools, as well as the delivery of training and innovative practices to targeted smallholder farmers.