A New Subspecies of Oriente Warbler Teretistris Fornsi from Pico Turquino

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Castro Same Cuba

New Castro, Same Cuba Political Prisoners in the Post-Fidel Era Copyright © 2009 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-562-8 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org November 2009 1-56432-562-8 New Castro, Same Cuba Political Prisoners in the Post-Fidel Era I. Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ....................................................................................................................... 7 II. Illustrative Cases ......................................................................................................................... 11 Ramón Velásquez -

Your Day-By-Day Itinerary

Your Day-by-Day Itinerary With the long-awaited dawn of a new era of relations between the U.S. and Cuba, Grand Circle Foundation is proud to introduce a new 13-day journey revealing the sweep of this once-forbidden Caribbean island’s scenic landscapes, colonial charm, and cultural diversity. Witness the winding lanes of colonial gem Camaguey, the magic of Spanish- influenced Remedios—and the electricity of Havana, a vibrant city with a revolutionary past and a bright future. And immerse yourself in Cuban culture during stops at schools, homes, farms, and artist workshops— while dining in family-run paladares and casas particulares. Join us on this new People-to-People program and experience the wonders of Cuba on the brink of historic transformation. Day 1 Arrive Miami After arriving in Miami today and transferring to your hotel, meet with members of your group for a Welcome Briefing and what to expect for your charter flight to Camaguey tomorrow (Please note: No meals are included while you are in Miami). D2DHotelInfo Day 2 Camaguey This morning we fly to Camaguey, Cuba. Upon arrival, we’ll be met by our Cuban Trip Leader. Then, we begin a walking tour of Camaguey. Founded as a port town in 1514—and the sixth of Cuba’s original seven villas—within 14 years Camaguey was moved inland. The labyrinthine streets and narrow squares were originally meant to confuse marauding pirates (the notorious privateer Sir Henry Morgan once sacked Camaguey), and during our stay, we’ll view the city’s lovely mix of colonial homes and plazas in its well-preserved histori- cal center, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. -

Travel Weekly Secaucus, New Jersey 29 October 2019

Travel Weekly Secaucus, New Jersey 29 October 2019 Latest Cuba restrictions force tour operators to adjust By Robert Silk A tour group in Havana. Photo Credit: Action Sports/Shutterstock The Trump administrations decision to ban commercial flights from the U.S. to Cub an destinations other than Havana could cause complications for tour operators. However, where needed, operators will have the option to use charter flights as an alternative. The latest restrictions, which take effect during the second week of December, will put an end to daily American Airlines flights from Miami to the Cuban cities of Camaguey, Hoguin, Santa Clara, Santiago and Varadero. JetBlue will end flights from Fort Lauderdale to Camaguey, Holguin and Santa Clara. In a letter requesting the Department of Transportation to issue the new rules, secretary of state Mike Pompeo wrote that the purpose of restrictions is to strengthen the economic consequences of the Cuban governments "ongoing repression of the Cuban people and its support for Nicholas Maduro in Venezuela." The restrictions dont directly affect all Cuba tour operators. For example, Cuba Candela flies its clients in and out of Havana only, said CEO Chad Olin. But the new rules will force sister tour operators InsightCuba and Friendly Planet to make adjustments, said InsightCuba president Tom Popper. In the past few months, he explained, Friendly Planet’s "Captivating Cuba" tour and InsightCubas "Classic Cuba" tour began departing Cuba from the north central city of Santa Clara. Now those itineraries will go back to using departure flights from Havana. As a result, guests will leave Cienfuegos on the last day of the tour to head back to Havana for the return flight. -

Distribution, Abundance, and Status of Cuban Sandhill Cranes (Grus Canadensis Nesiotes)

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/250071729 Distribution, Abundance, and Status of Cuban Sandhill Cranes (Grus canadensis nesiotes) Article in The Wilson Journal of Ornithology · September 2010 DOI: 10.1676/09-174.1 CITATIONS READS 2 66 2 authors, including: Felipe Chavez-Ramirez Gulf Coast Bird Observatory 45 PUBLICATIONS 575 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Felipe Chavez-Ramirez on 09 January 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND STATUS OF CUBAN SANDHILL CRANES (GRUS CANADENSIS NESIOTES) XIOMARA GALVEZ AGUILERA1,3 AND FELIPE CHAVEZ-RAMIREZ2,4 Published by the Wilson Ornithological Society The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 122(3):556–562, 2010 DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND STATUS OF CUBAN SANDHILL CRANES (GRUS CANADENSIS NESIOTES) XIOMARA GALVEZ AGUILERA1,3 AND FELIPE CHAVEZ-RAMIREZ2,4 ABSTRACT.—We conducted the first country-wide survey between 1994 and 2002 to examine the distribution, abundance, and conservation status of Sandhill Crane (Grus canadensis nesiotes) populations throughout Cuba. Ground or air surveys or both were conducted at all identified potential areas and locations previously reported in the literature. We define the current distribution as 10 separate localities in six provinces and the estimated total number of cranes at 526 individuals for the country. Two populations reported in the literature were no longer present and two localities not previously reported were discovered. The actual number of cranes at two localities was not possible to evaluate due to their rarity. Only four areas (Isle of Youth, Matanzas, Ciego de Avila, and Sancti Spiritus) each support more than 70 cranes. -

Cuba: Camagüey, Sierra De Cubitas

Cuba: Camagüey, Sierra de Cubitas 08 Rapid Biological Inventories : 08 Cuba: Camagüey, Sierra de Cubitas THE FIELD MUSEUM ograms 2496, USA Drive vation Pr – e 12.665.7433 5 3 r / Partial funding by Illinois 6060 , onmental & Conser .fieldmuseum.org/rbi 12.665.7430 F Medio Ambiente de Camagüey 3 T Chicago 1400 South Lake Shor www The Field Museum Envir Financiado po John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Instituciones Participantes / Participating Institutions The Field Museum Museo Nacional de Historia Natural de Cuba Centro de Investigaciones de Rapid Biological Inventories Rapid biological rapid inventories 08 Cuba: Camagüey, Sierra de Cubitas Luis M. Díaz,William S.Alverson, Adelaida Barreto Valdés, y/and TatzyanaWachter, editores/editors ABRIL/APRIL 2006 Instituciones Participantes /Participating Institutions The Field Museum Museo Nacional de Historia Natural de Cuba Centro de Investigaciones de Medio Ambiente de Camagüey LOS INFORMES DE LOS INVENTARIOS BIOLÓGICOS RÁPIDOS SON Cita sugerida/Suggested citation PUBLICADOS POR/RAPID BIOLOGICAL INVENTORIES REPORTS ARE Díaz, L., M., W. S. Alverson, A. Barreto V., y/ and T. Wachter. 2006. PUBLISHED BY: Cuba: Camagüey, Sierra de Cubitas. Rapid Biological Inventories Report 08. The Field Museum, Chicago. THE FIELD MUSEUM Environmental and Conservation Programs Créditos fotográficos/Photography credits 1400 South Lake Shore Drive Carátula / Cover: En la Sierra de Cubitas, hay una inusual frecuencia Chicago Illinois 60605-2496, USA del chipojo ceniciento (Chamaeleolis chamaeleonides, Iguanidae), T 312.665.7430, F 312.665.7433 tanto los adultos como los juveniles. Esta especie incluye en www.fieldmuseum.org su dieta gran cantidad de caracoles, que son muy comunes en las Editores/Editors rocas y los suelos calizos de la Sierra. -

Chamaeleolis” Species Group from Eastern Cuba

Acta Soc. Zool. Bohem. 76: 45–52, 2012 ISSN 1211-376X Anolis sierramaestrae sp. nov. (Squamata: Polychrotidae) of the “chamaeleolis” species group from Eastern Cuba Veronika Holáňová1,3), Ivan REHÁK2) & Daniel FRYNTA1) 1) Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Charles University in Prague, Viničná 7, CZ–128 43 Praha 2, Czech Republic 2) Prague Zoo, U Trojského zámku 3, CZ–171 00 Praha 7, Czech Republic 3) Corresponding author: e-mail: [email protected] Received 10 February 2012; accepted 16 April 2012 Published 15 August 2012 Abstract. A new species of anole, Anolis sierramaestrae sp. nov., belonging to the “chamaeleolis” species group of the family Polychrotidae, is described from the mountain region in the vicinity of La Mula village, Santiago de Cuba province, Cuba. The species represents the sixth so far known species of the “chamaeleolis” species group. It resembles Anolis chamaeleonides Duméril et Bibron, 1837, but differs markedly in larger body size, long and narrow head shape, higher number of barb-like scales on dewlap, small number of large lateral scales on the body and dark-blue coloration of the eyes. Key words. Taxonomy, new species, herpetofauna, Polychrotidae, Chamaeleolis, Anolis, Great Antilles, Caribbean, Neotropical region. INTRODUCTION False chameleons of the genus Anolis Daudin, 1802 represent a highly ecologically specialized and morphologically distinct and unique clade endemic to Cuba Island (Cocteau 1838, Beuttell & Losos 1999, Schettino 2003, Losos 2009). This group has been traditionally recognized as a distinct genus Chamaeleolis Cocteau, 1838 due to its multiple derived morphological, eco- logical and behavioural characters. Recent studies discovering the cladogenesis of anoles have placed this group within the main body of the tree of Antillean anoles as a sister group of a small clade consisting of the Puerto Rican species Anolis cuvieri Merrem, 1820 and hispaniolan A. -

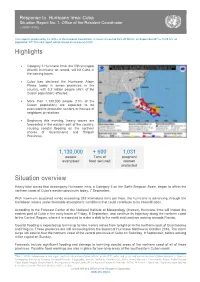

Highlights Situation Overview

Response to Hurricane Irma: Cuba Situation Report No. 1. Office of the Resident Coordinator ( 07/09/ 20176) This report is produced by the Office of the Resident Coordinator. It covers the period from 20:00 hrs. on September 06th to 14:00 hrs. on September 07th.The next report will be issued on or around 08/09. Highlights Category 5 Hurricane Irma, the fifth strongest Atlantic hurricane on record, will hit Cuba in the coming hours. Cuba has declared the Hurricane Alarm Phase today in seven provinces in the country, with 5.2 million people (46% of the Cuban population) affected. More than 1,130,000 people (10% of the Cuban population) are expected to be evacuated to protection centers or houses of neighbors or relatives. Beginning this evening, heavy waves are forecasted in the eastern part of the country, causing coastal flooding on the northern shores of Guantánamo and Holguín Provinces. 1,130,000 + 600 1,031 people Tons of pregnant evacuated food secured women protected Situation overview Heavy tidal waves that accompany Hurricane Irma, a Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Scale, began to affect the northern coast of Cuba’s eastern provinces today, 7 September. With maximum sustained winds exceeding 252 kilometers (km) per hour, the hurricane is advancing through the Caribbean waters under favorable atmospheric conditions that could contribute to its intensification. According to the Forecast Center of the National Institute of Meteorology (Insmet), Hurricane Irma will impact the eastern part of Cuba in the early hours of Friday, 8 September, and continue its trajectory along the northern coast to the Central Region, where it is expected to make a shift to the north and continue moving towards Florida. -

A Phase III Clinical Trial of the Epidermal Growth Factor Vaccine Cimavax-EGF

Author Manuscript Published OnlineFirst on February 29, 2016; DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0855 Author manuscripts have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet been edited. 1 Clinical Cancer Research (CCR) Category: Cancer Therapy: Clinical Title Page A Phase III Clinical Trial of the Epidermal Growth Factor Vaccine CIMAvax-EGF as Switch Maintenance Therapy in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Authors: Pedro C. Rodrigueza*, Xitllaly Popaa, Odeth Martínezb, Silvia Mendoza c, Eduardo Santiesteband, Tatiana Crespoe, Rosa M. Amadorf, Ricardo Fleytasg, Soraida C. Acostah, Yanine Oteroi, Gala N. Romeroj, Ana de la Torrek, Mireisysis Calal, Lina Arzuagam, Loisell Vellon, Delmayris Reyes0, Niurka Futielp, Teresa Sabatesq, Mauricio Catalar, Yoanna Floress, Beatriz Garciaa, Carmen Viadaa, Patricia Lorenzoa, Maria A. Marrerot, Liuba Alonsot, Jenely Parrat, Nadia Aguilera t, Yaisel Pomaresa, Patricia Sierraa, Gryssell Rodrígueza, Zaima Mazorraa, Agustin Lagea, Tania Crombeta, Elia Neningeru. a Centre for Molecular Immunology, Havana, Cuba b Vladimir I. Lenin University Hospital, Holguín Province, Cuba. c Manuel Ascunce University Hospital, Camagüey Province, Cuba. d José L. Lopez Tabranes University Hospital, Matanzas Province, Cuba. e Benefico Jurídico Pneumological Hospital, Havana, Cuba f III Congreso University Hospital, Pinar del Rio Province, Cuba. g Salvador Allende University Hospital, Havana, Cuba. h Saturnino Lora University Hospital, Santiago de Cuba Province, Cuba. i Camilo Cienfuegos University Hospital, Sancti Spiritus Province, Cuba. j Carlos M. de Céspedes University Hospital, Granma Province, Cuba. k Celestino Hernández University Hospital, Villa Clara Province, Cuba. Downloaded from clincancerres.aacrjournals.org on September 30, 2021. © 2016 American Association for Cancer Research. Author Manuscript Published OnlineFirst on February 29, 2016; DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0855 Author manuscripts have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet been edited. -

Office of the Resident Coordinator in Cuba Subject

United Nations Office of the Resident Coordinator in Cuba From: Office of the Resident Coordinator in Cuba Subject: Situation Report No. 6 “Hurricane IKE”- September 16, 2008- 18:00 hrs. Situation: A report published today, September 16, by the official newspaper Granma with preliminary data on the damages caused by hurricanes GUSTAV and IKE asserts that they are estimated at 5 billion USD. The data provided below is a summary of official data. Pinar del Río Cienfuegos 25. Ciego de Ávila 38. Jesús Menéndez 1. Viñales 14. Aguada de Pasajeros 26. Baraguá Holguín 2. La palma 15. Cumanayagua Camagüey 39. Gibara 3. Consolación Villa Clara 27. Florida 40. Holguín 4. Bahía Honda 16. Santo Domingo 28. Camagüey 41. Rafael Freyre 5. Los palacios 17. Sagüa la grande 29. Minas 42. Banes 6. San Cristobal 18. Encrucijada 30. Nuevitas 43. Antilla 7. Candelaria 19. Manigaragua 31. Sibanicú 44. Mayarí 8. Isla de la Juventud Sancti Spíritus 32. Najasa 45. Moa Matanzas 20. Trinidad 33. Santa Cruz Guantánamo 9. Matanzas 21. Sancti Spíritus 34. Guáimaro 46. Baracoa 10. Unión de Reyes 22. La Sierpe Las Tunas 47. Maisí 11. Perico Ciego de Ávila 35. Manatí 12. Jagüey Grande 23. Managua 36. Las Tunas 13. Calimete 24. Venezuela 37. Puerto Padre Calle 18 No. 110, Miramar, La Habana, Cuba, Apdo 4138, Tel: (537) 204 1513, Fax (537) 204 1516, [email protected], www.onu.org.cu 1 Cash donations in support of the recovery efforts, can be made through the following bank account opened by the Government of Cuba: Account Number: 033473 Bank: Banco Financiero Internacional (BFI) Account Title: MINVEC Huracanes restauración de daños Measures adopted by the Government of Cuba: The High Command of Cuba’s Civil Defense announced that it will activate its centers in all of Cuba to direct the rehabilitation of vital services that have been disrupted by the impact of Hurricanes GUSTAV and IKE. -

Squamata: Tropidophiidae)

caribbean herpetology note Easternmost record of the Cuban Broad-banded Trope, Tropidophis feicki (Squamata: Tropidophiidae) Tomás M. Rodríguez-Cabrera1*, Javier Torres2, and Ernesto Morell Savall3 1Sociedad Cubana de Zoología, Cuba. 2 Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 66045, USA. 3Área Protegida “Sabanas de Santa Clara,” Empresa Nacional para la Protección de la Flora y la Fauna, Villa Clara 50100, Cuba. *Corresponding author ([email protected]) Edited by: Robert W. Henderson. Date of publication: 14 May 2020. Citation: Rodríguez-Cabrera TM, Torres J, Morell Savall E (2020) Easternmost record of the Cuban Broad-banded Trope, Tropidophis feicki (Squa- mata: Tropidophiidae), of Cuba. Caribbean Herpetology, 71, 1-3. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31611/ch.71 Tropidophis feicki Schwartz, 1957 is restricted to densely forested limestone mesic areas in western Cuba (Schwartz & Henderson 1991; Henderson & Powell 2009). This species has been reported from about 20 localities distributed from near Guane, in Pinar del Río Province, to Ciénaga de Zapata, in Matanzas Province Rivalta et al., 2013; GBIF 2020; Fig. 1). On 30 June 2009 and on 22 December 2011 we found an adult male and an adult female Tropidophis feicki (ca. 400 mm SVL; Fig. 2), respectively, at the entrance of the “Cueva de la Virgen” hot cave (22.8201, -80.1384; 30 m a.s.l.; WGS 84; point 14 in Fig. 1). The cave is located within “Mogotes de Jumagua” Ecological Reserve, Sagua La Grande Municipality, Villa Clara Province. This locality represents the first record of this species for central Cuba, particularly for Villa Clara Province. -

Support for New Decentralization Initiatives and Identification of the Next Actions

68 C&D•№9•2013 C&D•№9•2013 69 Olga Rufins Machin Anabel Álvarez Paz SUPPORT FOR NEW National Programme Officer and Programme assistant of the Coordinator of the Portal of Culture UNESCO Regional Office for of the UNESCO Regional Office for Culture in Latin America and the Culture in Latin America and the Caribbean, Havana, Cuba DECENTRALIZATION Caribbean, Havana, Cuba he UNESCO Regional Office for Culture in Latin including 46 women. This diagnosis provided the basis for the America and the Caribbean, based in Havana, selection of the artisans to be included in the programme, INITIATIVES AND T since October 2009 has participated in the Joint and allowed characterize the state of the productions and the Programme “Support for new decentralization initiatives and identification of the next actions. This methodological guide production stimulation in Cuba,” within the framework of can be implemented in any territory. the Programme Area Private Sector and Development, an ALVAREZ RUFINS/A. O. ©UNESCO/ initiative that was developed with the support of the Fund Later, under the slogan “For a Better Product,” eight PRODUCTION for the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals workshops were organized for 219 artisans and local directors, (MDG-F). including 156 women. These training actions made it possible to update design and quality criteria, diversify production, UNESCO and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the introduce the use of environmentally friendly fixing agents United Nations (FAO), under the leadership of the United and natural dyes from local plants and substances, and STIMULATION IN CUBA Nations Development Programme (UNDP), have joined involve artisans who did not usually work with natural fibres forces with numerous local and national counterparts. -

Introduced Amphibians and Reptiles in the Cuban Archipelago

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 10(3):985–1012. Submitted: 3 December 2014; Accepted: 14 October 2015; Published: 16 December 2015. INTRODUCED AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES IN THE CUBAN ARCHIPELAGO 1,5 2 3 RAFAEL BORROTO-PÁEZ , ROBERTO ALONSO BOSCH , BORIS A. FABRES , AND OSMANY 4 ALVAREZ GARCÍA 1Sociedad Cubana de Zoología, Carretera de Varona km 3.5, Boyeros, La Habana, Cuba 2Museo de Historia Natural ”Felipe Poey.” Facultad de Biología, Universidad de La Habana, La Habana, Cuba 3Environmental Protection in the Caribbean (EPIC), Green Cove Springs, Florida, USA 4Centro de Investigaciones de Mejoramiento Animal de la Ganadería Tropical, MINAGRI, Cotorro, La Habana, Cuba 5Corresponding author, email: [email protected] Abstract.—The number of introductions and resulting established populations of amphibians and reptiles in Caribbean islands is alarming. Through an extensive review of information on Cuban herpetofauna, including protected area management plans, we present the first comprehensive inventory of introduced amphibians and reptiles in the Cuban archipelago. We classify species as Invasive, Established Non-invasive, Not Established, and Transported. We document the arrival of 26 species, five amphibians and 21 reptiles, in more than 35 different introduction events. Of the 26 species, we identify 11 species (42.3%), one amphibian and 10 reptiles, as established, with nine of them being invasive: Lithobates catesbeianus, Caiman crocodilus, Hemidactylus mabouia, H. angulatus, H. frenatus, Gonatodes albogularis, Sphaerodactylus argus, Gymnophthalmus underwoodi, and Indotyphlops braminus. We present the introduced range of each of the 26 species in the Cuban archipelago as well as the other Caribbean islands and document historical records, the population sources, dispersal pathways, introduction events, current status of distribution, and impacts.