Protecting Greenbelt Wetlands How Effective Is Policy? Protecting Greenbelt Wetlands: How Effective Is Policy?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LAKE WILCOX PARK SELF-GUIDED TREE TOUR This Tour Includes 20 Species That Are Native to Southern Ontario

Why plant Lake Wilcox Park What is the urban forest? native species? Our urban forest consists of all the trees on Lake Wilcox Park is located on the eastern public and private property in Richmond Hill Native species adapt to local shorelines of Lake Wilcox, the largest lake on – the ones in your yard, the ones that line our water and soil conditions and the Oak Ridges Moraine. The park is home to a streets and those in our parks and natural areas. therefore require less water variety of wildlife and plants. It’s also a great place for our community to participate in fun activities. and maintenance. Urban forest benefits Richmond Hill’s urban forest provides many They provide habitat and valuable economic, social and environmental food for birds, mammals and services to the community. various insects. Some examples of these services include: • Increasing property values Native species improve local • Reducing energy use and costs biodiversity. • Improving physical health • Promoting psychological well-being • Strengthening communities • Reducing air pollution • Shading and cooling the air • Reducing flooding • Providing wildlife habitat Photo credits: ©2013 Charlotte Ankette / ©2018 David Slaughter Be an Urban Forest Steward! In the Community Citizens can help grow our urban forest by The Healthy Yards Program provides information volunteering to plant trees through the Town’s and resources about how to create healthy lawns Community Stewardship Program. and gardens by using native plants and eco-friendly products which can be purchased at a subsidized cost. At Home The largest portion of our existing trees are LEAF helps property owners plant trees and shrubs located on residential properties and caring at subsidized price and will help you get the right for existing trees is the most effective way of species in the right places with the right care so that For more information, please contact: maintaining a healthy urban forest. -

Lake Wilcox Parking Study

Final Report Lake Wilcox Parking Study Prepared for City of Richmond Hill by IBI Group April 17, 2020 IBI GROUP FINAL REPORT LAKE WILCOX PARKING STUDY Prepared for City of Richmond Hill Document Control Page CLIENT: City of Richmond Hill PROJECT NAME: Lake Wilcox Parking Study REPORT TITLE: Lake Wilcox Parking Study IBI REFERENCE: 121638 VERSION: 3.0 J:\121638_LakeWilcox\6.0_Technical\6.3_Tech- DIGITAL MASTER: Reports\5_FinalReport\TTR_LakeWilcox_FinalReport_20200416_3.0.docx ORIGINATOR: Adam Wenneman, Stefan Tsang REVIEWER: Peter Richards AUTHORIZATION: Peter Richards CIRCULATION LIST: 1.0 Draft Final Report HISTORY: 2.0 Revised Draft Final Report 3.0 Final Report ii IBI GROUP FINAL REPORT LAKE WILCOX PARKING STUDY Prepared for City of Richmond Hill Table of Contents 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 2 Data Collection .................................................................................................................... 2 Parking Utilization Surveys ...................................................................................... 2 2.1.1 Study Area .................................................................................................. 2 2.1.2 Parking Occupancy Survey Methodology ................................................... 4 2.1.3 Parking Utilization Results .......................................................................... 4 Park User Surveys .................................................................................................. -

Chapter One the Vision of A

Oak Ridges Trail Association 1992 - 2017 The Vision of a Moraine-wide Hiking Trail Chapter One CHAPTER ONE The Oak Ridges Moraine is defined by a sub-surface geologic formation. It is evident as a 170 km long ridge, a watershed divide between Lake Ontario to the south and Lake Simcoe, Lake Scugog and Rice Lake to the north. Prior to most THE VISION OF A MORAINE-WIDE HIKING TRAIL being harvested, Red Oak trees flourished along the ridge – hence its name. Appended to this chapter is an account of the Moraine’s formation, nature and Where and What is the Oak Ridges Moraine? history written by two Founding Members of the Oak Ridges Trail Association. 1 Unlike the Niagara Escarpment, the Oak Ridges Moraine is not immediately observed when travelling through the region. During the 1990s when the Oak The Seeds of the Vision Ridges Moraine became a news item most people in the Greater Toronto Area had no idea where it was. Even local residents and visitors who enjoyed its From the 1960s as the population and industrialization of Ontario, particularly particularly beautiful landscape characterized by steep rolling hills and substantial around the Golden Horseshoe from Oshawa to Hamilton grew rapidly, there was forests had little knowledge of its boundaries or its significance as a watershed. an increasing awareness of the stress this placed on the environment, particularly on the congested Toronto Waterfront and the western shore of Lake Ontario. The vision of a public footpath that would span the entire Niagara Escarpment - the Bruce Trail - came about in 1959 out of a meeting between Ray Lowes and Robert Bateman of the Federation of Ontario Naturalists. -

Town of Richmond Hill Terrestrial Biological I N V E N T O R Y Septembe R, 20 15

Town of Richmond Hill Terrestrial Biological Inventory and Assessment September, 2015 Report prepared by: Paul Prior, Fauna Biologist Natasha Gonsalves, Flora Biologist Patricia Moleirinho, GIS Technologist Reviewed by: Sue Hayes, Project Manager, Terrestrial Monitoring and Inventories Scott Jarvie, Associate Director, Environmental Monitoring and Data Management Section This report may be referenced as: Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA). 2015. Town of Richmond Hill: Terrestrial Biological Inventory and Assessment Town of Richmond Hill Terrestrial Biological I n v e n t o r y Septembe r, 20 15 Table of Contents p a g e 1.0 Introduction ......................................................................................... 1 1.1 TRCA’s Terrestrial Natural Heritage Program ............................................................... 1 2.0 Study Area Location and History ........................................................ 3 3.0 Inventory Methodology .......................................................................... 5 3.1 Landscape Analysis ...................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Vegetation Communities, Flora and Fauna Species ..................................................... 8 4.0 Results and Discussion ....................................................................... 11 4.1 Regional Context ........................................................................................................ 11 4.2 Habitat Patch Findings for -

Lake Wilcox SNAP Embracing Nature in the Community Lake Wilcox SNAP Embracing Nature in the Community

Lake Wilcox SNAP Embracing Nature in the Community Lake Wilcox SNAP Embracing Nature in the Community Sustainable Neighbourhood Retrofit Action Plans Lake Wilcox is a unique local treasure – the largest (SNAPs) help established communities improve kettle lake on the ecologically significant Oak Ridges environmental conditions, reduce resource use and Moraine. The surrounding neighbourhood has evolved prepare for climate change, while meeting important from a 1940s cottage community to a growing suburban objectives of their residents. The Lake Wilcox SNAP aims community in the GTA (Figure 1, Box 2). Located in the to motivate local stewardship of unique natural features. headwaters of the historic Humber River watershed, the It is the product of an innovative, integrated approach community of Oak Ridges is surrounded by provincially to urban and suburban retrofit challenges in existing significant wetlands and stands of forest, home to neighbourhoods. One of five pilots in the Greater Toronto sensitive plant, bird, amphibian and fish species. Lake Area (GTA), the Lake Wilcox SNAP was developed by Wilcox and the Lake Wilcox Park draw visitors from near Toronto and Region Conservation (TRCA) in partnership and far. Residents and visitors have been drawn to live with the Regional Municipality of York, Town of Richmond and play here since Aboriginals inhabited the area 10,000 Hill, Oak Ridges Friends of the Environment (ORFE) and years ago. However, ongoing residential development and other community stakeholders (Box 1). growing numbers of visitors to the area stress its highly- valued natural features. A wetland at Ashfield Drive. 1 Lake Wilcox SNAP Embracing Nature in the Community Elevated phosphorus levels in the Lake are an ongoing population’s ecological footprint and improve overall concern. -

Bayview Avenue Extension Project

Bayview Avenue Extension Project Submission to:: Transportation Association of Canada for the Environmental Achievement Award 2002 Abstract The Bayview Avenue Extension project is a deserving candidate for the 2002 Environmental Achievement Award for its innovative design used to minimize environmental impacts, at the same time, improving environmental features and enhancing knowledge of locally significant ecosystem elements, in particular a nationally threatened amphibian species. The project features these innovative environmental achievements: Environmentally Responsible Road Alignment successfully mitigated impacts to the nearby Jefferson Forest, Lake Wilcox, Forester March and adjacent wetland areas. Wetland Habitat Creation Project led to the development of diverse habitat zones for a variety of animal and plant species. Amphibian Roadway Crossings were specifically designed to protect and enhance the amphibian population, in particular the Jefferson Salamander, while adding to research and knowledge base of a rare, nationally threatened species. Jefferson Ravine Bridge Crossing provides unimpeded passage for large and small mammals, including white-tailed deer, reptiles and amphibians, working with existing topography to achieve a unique crossing feature. Extensive Vegetation and Landscaping Enhancements screen nearby sensitive areas from roadway intrusions and provided intensified buffering to disturbed areas. Detailed Environmental Analysis was completed to ensure complete compliance with environmental legislation for the Oak Ridges Moraine. Project Details - Bayview Avenue Extension • Four-kilometre, two-lane rural arterial road • Grading constructed for an ultimate four-lane facility • Located within the Town of Richmond Hill and is situated on the Oak Ridges Moraine • Total gross expenditures for the project approximately $ 16 million • Fully funded and maintained by the Regional Municipality of York. -

The Humber River: the 10-Year Monitoring Report for the Canadian Heritage Rivers System October 2009 Lower Humber Valley, Toronto, TRCA, 2008

THE HUMBER RIVER: THE 10-YEAR MONITORING REPORT FOR THE CANADIAN HERITAGE RIVERS SYSTEM October 2009 Lower Humber Valley, Toronto, TRCA, 2008 THE HUMBER CHALLENGE Our challenge is to protect and enhance the Humber River watershed as a vital and healthy ecosystem where we live, work and play in harmony with the natural environment. GUIDING PRINCIPLES To achieve a healthy watershed, we should: • Increase awareness of the watershed’s resources • Protect the Humber River as a continuing source of clean water • Celebrate, regenerate, and preserve our natural, historical and cultural heritage • Increase community stewardship and take individual responsibility for the health of the Humber River • Establish linkages and promote partnerships among communities • Build a strong watershed economy based on ecological health, and • Promote the watershed as a destination of choice for recreation and tourism The Humber River: The 10-Year Monitoring Report for the Canadian Heritage Rivers System i FRAGMENT: THE VALLEY Like a sweet wine flowing from the glass, the Humber of my boyhood years! First the stretch of the river valley as I knew it best, running south from Dundas Street to my beloved stone marvel of the Old Mill Bridge, a scant mile to the south, not forgetting to count a quarter-mile jog to the east halfway down to heighten the wonderment. What force of ten million years’ cunning erosion, the relentless path of an awkward giant carving out for himself great steps one by one as he strides on and on, thirsty now for a great cold draught of Lake Ontario water! What sheer-climbing cliffs with the history of planet Earth carved in each layer of shale reaching up a hundred feet from the shining valley floor, the littered rocks of the river …. -

Lake Wilcox Park Pay Parking

Staff Report for Council Meeting Date of Meeting: May 27, 2020 Report Number: SRCS.20.13 Department: Community Services Division: Community Standards Subject: Lake Wilcox Park Pay Parking Purpose: To implement pay parking in the Lake Wilcox Park parking lots. Recommendations: a) That Staff Report SRCS.20.13 be received; b) That the Lake Wilcox Parking Study prepared by IBI Group, dated April 17, 2020 (Attachment 1) be received; c) That the Commissioner of Community Services be authorized to negotiate, enter into, and execute an agreement with Precise Park to implement pay parking at Lake Wilcox Park; d) That By-law No. 37-20 (Attachment 2 to staff report SRCS.20.13) be enacted to amend the Parking Regulation By-law No. 402-89 and Municipal Code Chapter 1116 regarding the regulation of parking within the City of Richmond Hill; e) That By-law No. 18-20 (Attachment 3 to staff report SRCS.20.13) be enacted to amend Schedules “A” and “B” of the Administrative Penalty By-law No. 69-16; e) That By-law No. 38-20 (Attachment 4 to staff report SRCS.20.13) be enacted to amend the Tariff of Fees By-law No. 108-19 to include $4 per hour and $5 per hour fees for parking at Lake Wilcox Park applicable to all vehicles not registered to individuals living in Richmond Hill. f) That $10,000 be allocated from the Transportation Network Reserve Fund to the Roads Operating Budget to fund the regulatory signage necessary to implement parking restrictions on residential streets in the vicinity of Lake Wilcox Park as described herein. -

A Guide to Parks & Trails in Richmond Hill

parksandtrails_front9.qxd 10/14/05 9:40 AM Page 1 The Benefits of Outdoor Recreation About This Guide Our Showcase of Parks • Parks and natural environ- ments have great spiritual meaning for many. Get out and participate in one of the many recrrecreationaleational activities • Outdoor recreation is one Briar Nine Park & Reserve #18 on Map French Royalist Park #47 on Map Headwaters Park #60 on Map Hunter's Point Wildlife Park #70 on Map of the best approaches to that can be done on our trail sys- envirenvironmentalonmental education — tem such as: hiking, cycling, The Town of Richmond Hill’s Parks, Recreation and a key to long term sustain- jogging and bird watching. Culture Department is pleased to provide this Parks & Experience breathtaking natural features typical of the Oak Did you know that aristocrats settled in the Richmond Hill The design of Headwaters Park The creation of Hunter’s Point Wildlife Park involved a ability. Trails Guide as a comprehensive reference to our unique Ridges Moraine as you follow the trails at Briar Nine Park area after the French Revolution? Visit French Royalist Park was inspirinspireded by its significant unique and innovative design that aimed to establish • Trail and pathway systems and exciting park and open space system. Richmond Hill & Reserve. Keep your eyes peeled and your ears tuned — and browse through the signs to find more information about location adjacent to the habitat for wildlife. This park is worth a visit in the spring save energy and prprotectotect air quality by encouraging non- contains an unbelievable amount of park and open space at this park there’s a chance to see or hear wildlife native to the history of early French settlers. -

Lake Wilcox Neighbourhood SNAP Richmond Hill, Ontario

Lake Wilcox Neighbourhood SNAP Richmond Hill, Ontario www.sustainableneighbourhoods.ca TRANSFORMING EXISTING NEIGHBOURHOODS INTO GREENER, HEALTHIER PLACES TO LIVE, WORK AND PLAY SNAP - An Action Plan for Change Lake Wilcox SNAP Study Area The Sustainable Neighbourhood Retrofit Action Plan (SNAP) is part of a pilot program to help established communities become more environmentally friendly and prepare for climate change. The SNAP brings together residents, businesses, community groups and government agencies to develop a science-based action plan for change that fits the needs of the neighbourhood. In partnership with York Region, the Town of Richmond Hill, and local groups, Toronto and Region Conservation is leading a SNAP for the “Lake Wilcox” Neighbourhood in the Oak Ridges area of Richmond Hill. What does Lake Wilcox SNAP include? The Lake Wilcox SNAP is a comprehensive action-oriented plan, developed to suit the needs of this growing and changing community. Considering the plentiful natural heritage features located here, the action plan focuses on Embracing Nature in the Community through 3 primary action areas: residential eco-landscaping, visitor stewardship, and green renovations and energy. This integrated action plan finds ways to improve water quality in Lake Wilcox, reduce storm runoff, enhance natural areas, and reduce water use. Finally, the plan strives to inspire long time cottagers and residents, new homeowners, businesses and visitors to work together towards environmental sustainability and strengthened neighbourhood identity. About the Lake Wilcox Neighbourhood The Lake Wilcox neighbourhood is located within the larger community of Oak Ridges in the Town of Richmond Hill, York Region. It is home to a diverse and growing community and it contains the largest Kettle Lake on the Oak Ridge Moraine - Lake Wilcox. -

Film Location Resource Guide

The Smart Place for Business Film Location Resource Guide BusinessRichmondHill.ca Ontario Canada RICHMOND GREEN SPORTS CENTRE AND PARK Table of Contents Richmond Hill Contact ..................................................................................................................... 1 Richmond Hill Locations (photos) .................................................................................................. 2 Filming in Ontario/Richmond Hill .................................................................................................... 6 Transportation ................................................................................................................................. 8 Climate ............................................................................................................................................. 9 Filmed in Richmond Hill ............................................................................................................... 10 Filming Locations in Richmond Hill ............................................................................................... 13 Tax Incentives ................................................................................................................................ 14 Grants and Funding ....................................................................................................................... 15 Filming Guidelines ....................................................................................................................... -

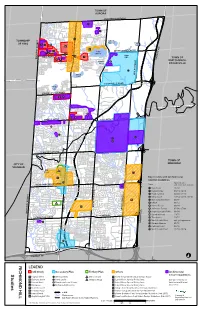

Map Identifying Lands Affected by Area-Specific

TOWN OF AURORA BLOOMINGTON ROAD 1 2 1 TOWNSHIP T Lake St. E George Haynes OF KING E R 3 a b Lake T d 4 S 0 T 4 4 S SDA SIDEROAD c Lake BETHE Y R A U 4 Wilcox 2 W H Swan H T 3 OAD G A KING R f Lake I TOWN OF B e H 5 Catfish T WHITCHURCH- 6 E Pond E STOUFFVILLE R T S E I i L S E Bond L Lake STOUFFVILLE ROAD Philips Lake JEFFERSON SIDEROAD g 7 8 h 9 GAMBLE ROAD 19TH AVENUE 10 11 j 15 12 ELGIN MILLS ROAD TOWN OF CITY OF MARKHAM VAUGHAN Mill m Pond 7 5 Key to sites with Architectural Control Guidelines k Approval date, IVE MAJOR MACKENZIE DR Name addendum date (mm/yy) 13 1 Oak Knoll 11/12 E 2 Sugarbridge 09/14, 02/16 U N 3 Hughey West 04/07, 01/16 E T T V E T E A 4 King South 10/14, 02/16, 05/16 E E E E R W R 5 T R 8 Bond (east & west) 03/15 E T I S T S V S 6 CASA 06/12 T n Y E S I E A L 7 R Harris Beech 08/14 B G 6 S U N E 8 H Jefferson Forest 07/08, 07/08 L O 4 T 0 Y A 9 Anglin/Longhill/19th 06/04 4 B Y 10 Gamble Road 10/11 16TH AVENUE A CARRVILLE ROAD W 11 The Grove 10/15 H G 12 I North Leslie West not yet approved 14 H 13 Garden Homes 01/15 14 Petrolia Court 02/16 15 North Leslie East 11/15, 05/16 l HIGHWAY 7 HIGHWAY 407 R LEGEND I C Inll Study Secondary Plan Tertiary Plan Others Architectural H S M Control Guidelines t a Hughey West i West Gormley m Benson Hunt 1 North Yonge Street Urban Design Study u O b Bathurst Street j North Leslie n Weldrick Road 2 Lake Wilcox Special Policy Area See above for list of d N c Puccini Drive k Downtown Local Centre 3 Lake Wilcox Special Policy Area Architectural Control i e Guidelines D d Elm Grove l Richmond Hill Centre 4 Lake Wilcox Special Policy Area s e Bond Crescent 5 Village Core Neighbourhood Design Guidelines H f Douglas Road 6 David Dunlap Observatory Park Master Plan I C.N.R.