Steve Wilson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeing (For) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2014 Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Benjamin Park, "Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623644. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-t267-zy28 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park Anderson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, College of William and Mary, 2005 Bachelor of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program College of William and Mary May 2014 APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Benjamin Park Anderson Approved by T7 Associate Professor ur Knight, American Studies Program The College -

Concert: Ithaca College Jazz Workshop Tuesday-Thursday Jazz Lab

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 12-5-2003 Concert: Ithaca College Jazz Workshop Tuesday-Thursday Jazz Lab Steve Brown Steve Wilson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Tuesday-Thursday Jazz Lab; Brown, Steve; and Wilson, Steve, "Concert: Ithaca College Jazz Workshop" (2003). All Concert & Recital Programs. 2900. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/2900 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. ITHACA COLLEGE JAZZ WORKSHOP Tuesday-Thursday Jazz Lab Steve Brown, musical director Steve Wilson, guest saxophone soloist Mean What You Say Thad Jones Rhythm-A-Ning Thelonious Monk Arr. Ryan Socrates Jessica's Day Quincy Jones The Dolphin Luis Eca Arr. Ray Brown Fantasy in "D" Cedar Walton Arr. Rufus Reid INTERMISSION There Will Never Be Another You Warren/Gordon Arr. Ray Brown Lisa Victor Feldman Arr. Yvonne Darancou A Joyful Noise Steve Wilson A Penthouse Dawn Oliver Nelson Willow Weep For Me AnnRonell Arr. Phil Woods Ford Hall Friday, December 5, 2003 8:15 p.m. Called by the Palm Beach Post "flawless, gifted with fabulous technique and a first-rate sense of what's musical," Steve Wilson has performed and recorded with the greatest names in jazz. A sampling of the musicians he has worked with includes Chick Corea, Dave Holland, Dianne Reeves, O.T.B., Donald Brown, Billy Childs, Don Byron, Bill Stewart, James Williams, and Mulgrew Miller. -

Downbeat.Com March 2014 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 U.K. DOWNBEAT.COM MARCH 2014 D O W N B E AT DIANNE REEVES /// LOU DONALDSON /// GEORGE COLLIGAN /// CRAIG HANDY /// JAZZ CAMP GUIDE MARCH 2014 March 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 3 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Kathleen Costanza Design Intern LoriAnne Nelson ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene -

Jonny King — Biography

Jonny King Biography Jonny King has been described by Downbeat as "one of the strongest piano voices" of his generation and a "bandleader who kicks ass." JazzTimes likewise wrote that he “represents the best of what jazz has to offer” as both a performer and composer. A native New Yorker, he grew up in the City's jazz clubs, participating first as a fan and then as a performer. Before he was a teenager, King had already performed onstage with Dizzy Gillespie and appeared on television at the piano alongside his early idol, Earl “Fatha” Hines. Before he was 20, he was already sitting in with Art Blakey and playing his first gigs in New York's many restaurants and clubs. King is primarily self-taught, having neither received any formal music education nor attended any jazz schools. He gratefully credits pianists Mulgrew Miller and Tony Aless as important influences, mentors and personal teachers. Beyond their private instruction, King learned music in the most old-school of ways -- by obsessively listening to records, attending jam sessions, and soaking up as much live and recorded music possible, from the most traditional to the most avant-garde. He continues to approach music the same way, both as a performer and composer. Beginning in the 1990s, King became a steady presence on the City's club scene, featuring his own bands at The Jazz Standard, Smalls, and legendary clubs like Sweet Basil's and Bradley's, his home-away-from-home, where he performed regularly both as leader and sideman. He toured as a member of Joshua Redman's Quartet and the Blue Note Records cooperative band OTB, and worked as the pianist in groups led by saxophonists Steve Wilson, Eddie Harris, Vincent Herring and many others. -

For Alto Saxophone and Piano Wade Howles University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research, Creative Activity, and Music, School of Performance - School of Music 2017 The nflueI nce of Jazz Elements in Don Freund's Sky Scrapings for Alto Saxophone and Piano Wade Howles University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent Part of the Composition Commons, and the Ethnomusicology Commons Howles, Wade, "The nflueI nce of Jazz Elements in Don Freund's Sky Scrapings for Alto Saxophone and Piano" (2017). Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music. 113. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent/113 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE INFLUENCE OF JAZZ ELEMENTS IN DON FREUND’S SKY SCRAPINGS FOR ALTO SAXOPHONE AND PIANO by Jason Wade Howles A DOCTORAL DOCUMENT Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Music Under the Supervision of Professor Paul Haar Lincoln, Nebraska December, 2017 THE INFLUENCE OF JAZZ ELEMENTS IN DON FREUND’S SKY SCRAPINGS FOR ALTO SAXOPHONE AND PIANO J. Wade Howles, D.M.A. University of Nebraska, 2017 Adviser: Paul Haar Jazz influence surfaces within traditional repertoire for the saxophone more often than other instruments. This is due to the saxophone’s close association with the jazz idiom. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

JAZZ GUITAR TRIO: an HOUR of SERIOUS JAZZ /October 16/3.00PM Gerry Gibbs Is a Grammy Nominated Drummer, Producer, Band Leader, Composer & Arranger

ST. CATHERINE OF SIENA MUSIC SERIES / CONCERTS IN THE CHAPEL PRESENTS JAZZ GUITAR TRIO: AN HOUR OF SERIOUS JAZZ /October 16/3.00PM Gerry Gibbs is a Grammy nominated Drummer, Producer, Band Leader, Composer & Arranger. As a Solo Artist, Gibbs has released 9 Jazz Recordings. His first, back in 1996, ‘Gerry Gibbs Sextet – The Thrasher’ features Saxophonist Ravi Coltrane with Quincy Jones as Executive Producer, while his last two recordings: ‘Gerry Gibbs & The Thrasher Dream Trio’, ’We’re Back’ and ‘Live In Studio’ feature Ron Carter & Kenny Barron. In 2014 and 2015, all three recordings topped the National Jazz Radio Charts. Gerry performed, recorded and toured with a who’s who in jazz, funk, electronic & world music, among them: McCoy Tyner, Stanley Clarke, Joe Henderson, James Moody, Patrice Rushen, Dewey Redman, Eddie Harris, Mike Stern, Larry Coryell, Randy Brecker, Tom Harrell, Brad Mehldau, Parliament Funkadelic & Electronic Music Pioneer Flying Lotus, to name but a few. GERRY GIBBS / DRUMS Essiet Okon Essiet an internationally renowned Bassist, having toured throughout the The Americas, Europe and Japan as part of the Blue Note Allstars and Danilo Perez's Motherland Project and with South African pianist Abdullah Ibrahim. A member of Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, Essiet performed and recorded with such notables as Benny Golson, Johnny Griffin, James Moody, Freddie Hubbard, Bobby Hutcherson, Cedar Walton, Pat Martino, Kenny Burrell, Jackie McLean, Kenny Barron, Louis Hayes, Art Farmer, Victor Lewis, Kenny Garrett, Kenny Kirkland ,Mulgrew Miller, Jeff "Tain " Watts, Mike Stern, Fort Apache Band, to highlight only a partial list. Currently, Essiet leads his own group called "IBO" named after a Nigerian tribe. -

Joe Henderson: a Biographical Study of His Life and Career Joel Geoffrey Harris

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 12-5-2016 Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career Joel Geoffrey Harris Follow this and additional works at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations © 2016 JOEL GEOFFREY HARRIS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School JOE HENDERSON: A BIOGRAPHICAL STUDY OF HIS LIFE AND CAREER A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Arts Joel Geoffrey Harris College of Performing and Visual Arts School of Music Jazz Studies December 2016 This Dissertation by: Joel Geoffrey Harris Entitled: Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Arts in the College of Performing and Visual Arts in the School of Music, Program of Jazz Studies Accepted by the Doctoral Committee __________________________________________________ H. David Caffey, M.M., Research Advisor __________________________________________________ Jim White, M.M., Committee Member __________________________________________________ Socrates Garcia, D.A., Committee Member __________________________________________________ Stephen Luttmann, M.L.S., M.A., Faculty Representative Date of Dissertation Defense ________________________________________ Accepted by the Graduate School _______________________________________________________ Linda L. Black, Ed.D. Associate Provost and Dean Graduate School and International Admissions ABSTRACT Harris, Joel. Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career. Published Doctor of Arts dissertation, University of Northern Colorado, December 2016. This study provides an overview of the life and career of Joe Henderson, who was a unique presence within the jazz musical landscape. It provides detailed biographical information, as well as discographical information and the appropriate context for Henderson’s two-hundred sixty-seven recordings. -

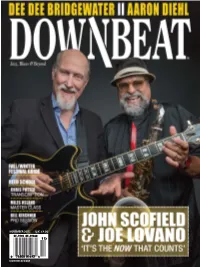

Downbeat.Com November 2015 U.K. £4.00

NOVEMBER 2015 2015 NOVEMBER U.K. £4.00 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT JOHN SCOFIELD « DEE DEE BRIDGEWATER « AARON DIEHL « ERIK FRIEDLANDER « FALL/WINTER FESTIVAL GUIDE NOVEMBER 2015 NOVEMBER 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Stephen Hall Editorial Intern Baxter Barrowcliff ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sam Horn 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; -

May 2008AAJ-NY.Qxd

NEW YORK May 2008 | No. 73 Your FREE Monthly Guide to the New York Jazz Scene newyork.allaboutjazz.com AHMAD JAMAL IT'S MAGIC Vince Giordano • George Garzone • Les Disques Victo • Dizzy’s Club • Event Calendar NEW YORK May is significant in the history of Miles Davis. Not only is the 26th the late trumpeter’s birthday but many of his most enduring works were New York@Night recorded during this month, including the Charlie Parker All-Stars (1948); the 4 Miles Davis-Tadd Dameron Quintet’s run in Paris (1949), most of the Workin’, Steamin’ and Relaxin’ triumvirate by the quintet with John Coltrane (1956), Miles Interview: Vince Giordano Ahead and At Carnegie Hall, both with the Gil Evans Orchestra (1957 and 1961 6 by Michael Hittman respectively); and the bulk of Miles in the Sky (1968). Now in May 2008, another chapter to the Miles Legacy will be written with an ambitious concert at Town Artist Feature: George Garzone Hall May 9th, “Miles From India”. A companion concert to a just-released album 7 by Matthew Miller of the same name, the concert brings together musicians who played with the legend throughout his career as well as a number of classical Indian musicians for Label Spotlight: Les Disques Victo what is billed as a “cross-cultural summit meeting”. Our Encore this month, 8 by Kurt Gottschalk guitarist Pete Cosey, is participating in what is sure to be a monumental event. But, as is typical for New York, the happenings don’t stop happening there. Club Profile: Dizzy’s Club Pianist Ahmad Jamal (Cover) brings his trio to Blue Note in a pre-release by Laurel Gross celebration of his first new album in three years, It’s Magic (Birdology-Dreyfus), due out in June. -

Zycopolis Productions

! ZYCOPOLIS PRODUCTIONS 24 RUE SAINT- LAZARE 69007 LYON – FRANCE TEL: +33 472 730 577 31 RUE BLANCHE 75009 PARIS – FRANCE [email protected] WWW.ZYCOPOLIS.COM ! ! A taylor-made approach of each project, constantly seeking the highest possible quality for each artist in order to reveal his own unique talent.! We’re a TV production company, created in 2002 with a unique goal - filming live shows and musical documentaries. Fully independent, we are praised for a custom made approach to each project, constantly seeking the highest possible quality for each artist in order to reveal their unique talents. ! Zycopolis is trusted by some of the most world's demanding artists like Herbie Hancock, Marcus Miller, Sonny Rollins, Melody Gardot, Coldplay, Maroon 5, Ike Turner, Francis Cabrel, Trust, Ben Harper, Al Jarreau, Steve Vai, George Benson, Kassav, Ibrahim Ferrer, Dee Dee Bridgewater and Youssou N’ Dour. We've filmed shows in many venues including Zénith, l’Olympia, Bercy, La Cigale, Le Bataclan, Le Cabaret Sauvage, The Sea Theater (Sète), The New Morning, the Stade de France and festivals such as Jazz à Vienne, Jazz à Juan, Garance Reggae Festival or Guitare en Scène.! ! We just love the music, and the beat goes on… JAZZ A VIENNE Years : 2011 - 2012 - 2013 Venue : Théâtre Antique de Vienne Broadcasters : France Ô - Arte Concert - Mezzo - Culturebox - Dailymotion - Trace TV 8 Mont-Blanc - Cinaps TV - Télé-Grenoble - TL7 - TLM - TLT AHMAD JAMAL 90 min - 2011 AL JARREAU 90 min - 2011 Live Broadcast on France Ô BATTLE ROYAL BASIE VS ELLINGTON -

The Jazz Messengers

The Jazz Messengers Steven Criado 2 décembre 2020 1 Introduction 1.1 Écoutes du 2 décembre 2020 — The Freedom Rider - Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers (The Freedom Rider, enregistré en 61, sorti en 64) — United - Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers (Roots & Herbs, enregistré en 61 pendant les sessions de Freedom Rider, sorti en 70) — Mr. Jin - Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers (Indestructible, 1964) — I’m Not So Sure - Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers (Anthenagin, 1973), écouter aussi la version de Roy Hargrove (Earfood, 2008) — Live des Jazz Messengers de 1974 au studio 104 de la Maison de la Radio (lien ci-dessous) — Witch Hunt - Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers (Album of the Year, 1981) 2 Freedom riders — arrêt de la cour suprême qui interdit la ségrégation dans les transports, en contradiction avec la loi Jim Crow issue du code noir appliquée dans les états du sud — des militants prennent les bus inter-états en 61, un premier bus partant de Wahsington à la Nouvelle-Orléan, est arrêté dans l’Alabama, à Anniston. Pneu crevé, incendie provoqué par la foule, les militants qui s’échappent du bus sont battus, les blessés ont du quitter l’hôpital par crainte de représailles — l’enregistrement de l’album d’Art Blakey à lieu 3 semaines après 1 3 ANNÉES 70 ET 80 DES MESSENGERS 2 — civil right movement, mouvement des droits civiques formé dans les années 50 rassemblant toutes les organisations noires (N.A.A.C.P, Urban League, S.N.C.C., le C.O.R.E., S.C.L.C), poursuit la lutte contre la ségrégation raciale dans la loi américaine, accès à l’éducation,