Travel Analysis Report for Tusayan Ranger District, Kaibab National Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Little Colorado River Project: Is New Hydropower Development the Key to a Renewable Energy Future, Or the Vestige of a Failed Past?

COLORADO NATURAL RESOURCES, ENERGY & ENVIRONMENTAL LAW REVIEW The Little Colorado River Project: Is New Hydropower Development the Key to a Renewable Energy Future, or the Vestige oF a Failed Past? Liam Patton* Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 42 I. THE EVOLUTION OF HYDROPOWER ON THE COLORADO PLATEAU ..... 45 A. Hydropower and the Development of Pumped Storage .......... 45 B. History of Dam ConstruCtion on the Plateau ........................... 48 C. Shipping ResourCes Off the Plateau: Phoenix as an Example 50 D. Modern PoliCies for Dam and Hydropower ConstruCtion ...... 52 E. The Result of Renewed Federal Support for Dams ................. 53 II. HYDROPOWER AS AN ALLY IN THE SHIFT TO CLEAN POWER ............ 54 A. Coal Generation and the Harms of the “Big Buildup” ............ 54 B. DeCommissioning Coal and the Shift to Renewable Energy ... 55 C. The LCR ProjeCt and “Clean” Pumped Hydropower .............. 56 * J.D. Candidate, 2021, University oF Colorado Law School. This Note is adapted From a final paper written for the Advanced Natural Resources Law Seminar. Thank you to the Colorado Natural Resources, Energy & Environmental Law Review staFF For all their advice and assistance in preparing this Note For publication. An additional thanks to ProFessor KrakoFF For her teachings on the economic, environmental, and Indigenous histories of the Colorado Plateau and For her invaluable guidance throughout the writing process. I am grateFul to share my Note with the community and owe it all to my professors and classmates at Colorado Law. COLORADO NATURAL RESOURCES, ENERGY & ENVIRONMENTAL LAW REVIEW 42 Colo. Nat. Resources, Energy & Envtl. L. Rev. [Vol. 32:1 III. ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS OF PLATEAU HYDROPOWER ............... -

Off-Road Vehicle Plan

United States Department of Agriculture Final Environmental Assessment Forest Service Tusayan Ranger District Travel Management Project April 2009 Southwestern Region Tusayan Ranger District Kaibab National Forest Coconino County, Arizona Information Contact: Charlotte Minor, IDT Leader Kaibab National Forest 800 S. Sixth Street, Williams, AZ 86046 928-635-8271 or fax: 928-635-8208 The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternate means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Printed on recycled paper Chapter 1 5 Document Structure 5 Introduction 5 Background 8 Purpose and Need 10 Existing Condition 10 Desired Condition 12 Proposed Action 13 Decision Framework 15 Issues 15 Chapter 2 - Alternatives 17 Alternatives Analyzed -

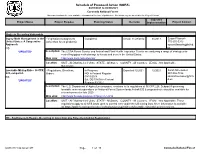

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2021 to 06/30/2021 Coronado National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2021 to 06/30/2021 Coronado National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Gypsy Moth Management in the - Vegetation management Completed Actual: 11/28/2012 01/2013 Susan Ellsworth United States: A Cooperative (other than forest products) 775-355-5313 Approach [email protected]. EIS us *UPDATED* Description: The USDA Forest Service and Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service are analyzing a range of strategies for controlling gypsy moth damage to forests and trees in the United States. Web Link: http://www.na.fs.fed.us/wv/eis/ Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Nationwide. Locatable Mining Rule - 36 CFR - Regulations, Directives, In Progress: Expected:12/2021 12/2021 Sarah Shoemaker 228, subpart A. Orders NOI in Federal Register 907-586-7886 EIS 09/13/2018 [email protected] d.us *UPDATED* Est. DEIS NOA in Federal Register 03/2021 Description: The U.S. Department of Agriculture proposes revisions to its regulations at 36 CFR 228, Subpart A governing locatable minerals operations on National Forest System lands.A draft EIS & proposed rule should be available for review/comment in late 2020 Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=57214 Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. These regulations apply to all NFS lands open to mineral entry under the US mining laws. -

Trip Planner

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon National Park Grand Canyon, Arizona Trip Planner Table of Contents WELCOME TO GRAND CANYON ................... 2 GENERAL INFORMATION ............................... 3 GETTING TO GRAND CANYON ...................... 4 WEATHER ........................................................ 5 SOUTH RIM ..................................................... 6 SOUTH RIM SERVICES AND FACILITIES ......... 7 NORTH RIM ..................................................... 8 NORTH RIM SERVICES AND FACILITIES ......... 9 TOURS AND TRIPS .......................................... 10 HIKING MAP ................................................... 12 DAY HIKING .................................................... 13 HIKING TIPS .................................................... 14 BACKPACKING ................................................ 15 GET INVOLVED ................................................ 17 OUTSIDE THE NATIONAL PARK ..................... 18 PARK PARTNERS ............................................. 19 Navigating Trip Planner This document uses links to ease navigation. A box around a word or website indicates a link. Welcome to Grand Canyon Welcome to Grand Canyon National Park! For many, a visit to Grand Canyon is a once in a lifetime opportunity and we hope you find the following pages useful for trip planning. Whether your first visit or your tenth, this planner can help you design the trip of your dreams. As we welcome over 6 million visitors a year to Grand Canyon, your -

Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument Foundation Document

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument Arizona Contact Information For more information about the Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument Foundation Document, contact: [email protected] or 435-688-3226 or write to: Superintendent, Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument, 345 E. Riverside Drive, St. George, UT 84790 Purpose Significance Significance statements express why Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument resources and values are important enough to merit designation as a national monument. Statements of significance describe the distinctive nature of the monument and why an area is important within a global, national, regional, and systemwide context. They focus on the most important resources and values that will assist in planning and management for the monument. • Spanning 320 million years, the exposed rock layers at Parashant National Monument provide a distinctly identifiable view of the geologic boundaries of the Colorado Plateau and Basin and Range regions, including evidence of the interaction between volcanic processes and native cultural communities. The extensive natural history reveals a robust fossil record and preserves museum-quality marine and ice age fossils. At GRAND CANYON-PARASHANT NATIONAL • Encompassing more than 1 million acres, a dramatic MONUMENT, the Bureau of Land elevational gradient from 1,200 to 8,000 feet, and transitional Management and the National zones of the Sonoran, Mojave, Great Basin, and Colorado Park Service cooperatively protect Plateau ecoregions, Parashant National Monument protects undeveloped, wild, and remote a biologically rich system of plant and animal life. northwestern Arizona landscapes • Parashant National Monument is one of the most rugged and their resources, while providing and remote landscapes remaining in the southwestern opportunities for solitude, primitive United States. -

Forest Insect and Disease Conditions in the Southwestern Region, 2008

United States Department of Forest Insect and Agriculture Forest Disease Conditions in Service Southwestern the Southwestern Region Forestry and Forest Health Region, 2008 July 2009 PR-R3-16-5 The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA's TARGET Center at (202) 720- 2600 (voice and TTY). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TTY). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Cover photo: Pandora moth caterpillar collected on the North Kaibab Ranger District, Kaibab National Forest. Forest Insect and Disease Conditions in the Southwestern Region, 2008 Southwestern Region Forestry and Forest Health Regional Office Salomon Ramirez, Director Allen White, Pesticide Specialist Forest Health Zones Offices Arizona Zone John Anhold, Zone Leader Mary Lou Fairweather, Pathologist Roberta Fitzgibbon, Entomologist Joel McMillin, Entomologist -

Grand Canyon.Com's Spring Travel Guide

Grand Canyon.com’s Spring Travel Guide Second Edition Helping You Get Even More Out of Your Grand Canyon Vacation! Thank you for choosing Grand Canyon.com as your Southwest destination specialist! You’ve chosen a truly extraordinary place for your spring vacation, and our mission is to help you get the most out of your trip. Having helped thousands of busy people like you plan their Grand Canyon vacations for over 20 years, our staff has made a few observations and picked up a few insider tips that can help save you time, money and hassle - sometimes all three at once! It was to that end that we presented our First Annual Spring Break Travel Guide in February. Since then, peoples’ response has been nothing short of overwhelming. But with spring break extending well into April this year, we realized that a few things needed updating in order for you to be as well informed as possible before hitting the road. It is to that end that we present: Grand Canyon.com’s First Annual Spring Travel Guide: The Second Edition Before you dig in, we recommend that you grab a few things: a map or road atlas, a pen and/or a highlighter, maybe a beverage, a few minutes of quiet time, and your “Grand Canyon Top Tours Brochure.” Let’s get started and get YOU* to the Grand Canyon! *Got most of your trip figured out already? Skip to Chapter 8 Traveler Tip 1 - Where’s It At and What Side Am I On? The Grand Canyon is in Northern Arizona. -

Of North Rim Pocket

Grand Canyon National Park National Park Service Grand Canyon Arizona U.S. Department of the Interior Pocket Map North Rim Services Guide Services, Facilities, and Viewpoints Inside the Park North Rim Visitor Center / Grand Canyon Lodge Campground / Backcountry Information Center Services and Facilities Outside the Park Protect the Park, Protect Yourself Information, lodging, restaurants, services, and Grand Canyon views Camping, fuel, services, and hiking information Lodging, camping, food, and services located north of the park on AZ 67 Use sunblock, stay hydrated, take Keep wildlife wild. Approaching your time, and rest to reduce and feeding wildlife is dangerous North Rim Visitor Center North Rim Campground Kaibab Lodge the risk of sunburn, dehydration, and illegal. Bison and deer can Park in the designated parking area and walk to the south end of the parking Operated by the National Park Service; $18–25 per night; no hookups; dump Located 18 miles (30 km) north of North Rim Visitor Center; open May 15 to nausea, shortness of breath, and become aggressive and will defend lot. Bring this Pocket Map and your questions. Features new interpretive station. Reservation only May 15 to October 15: 877-444-6777 or recreation. October 20; lodging and restaurant. 928-638-2389 or kaibablodge.com exhaustion. The North Rim's high their space. Keep a safe distance exhibits, park ranger programs, restroom, drinking water, self-pay fee station, gov. Reservation or first-come, first-served October 16–31 with limited elevation (8,000 ft / 2,438 m) and of at least 75 feet (23 m) from all nearby canyon views, and access to Bright Angel Point Trail. -

2010 General Management Plan

Montezuma Castle National Monument National Park Service Mo n t e z u M a Ca s t l e na t i o n a l Mo n u M e n t • tu z i g o o t na t i o n a l Mo n u M e n t Tuzigoot National Monument U.S. Department of the Interior ge n e r a l Ma n a g e M e n t Pl a n /en v i r o n M e n t a l as s e s s M e n t Arizona M o n t e z u MONTEZU M A CASTLE MONTEZU M A WELL TUZIGOOT M g a e n e r a l C a s t l e M n a n a g e a t i o n a l M e n t M P o n u l a n M / e n t e n v i r o n • t u z i g o o t M e n t a l n a a t i o n a l s s e s s M e n t M o n u M e n t na t i o n a l Pa r k se r v i C e • u.s. De P a r t M e n t o f t h e in t e r i o r GENERAL MANA G E M ENT PLAN /ENVIRON M ENTAL ASSESS M ENT General Management Plan / Environmental Assessment MONTEZUMA CASTLE NATIONAL MONUMENT AND TUZIGOOT NATIONAL MONUMENT Yavapai County, Arizona January 2010 As the responsible agency, the National Park Service prepared this general management plan to establish the direction of management of Montezuma Castle National Monument and Tu- zigoot National Monument for the next 15 to 20 years. -

North Kaibab Ranger District Travel Management Project Environmental Assessment

Environmental Assessment United States Department of Agriculture North Kaibab Ranger District Forest Service Travel Management Project Southwestern Region September 2012 Kaibab National Forest Coconino and Mohave Counties, Arizona Information Contact: Wade Christy / Recreation & Lands Kaibab National Forest - NKRD Mail: P.O.Box 248 / 430 S. Main St. Fredonia, AZ 86022 Phone: 928-643-8135 E-mail: [email protected] It is the mission of the USDA Forest Service to sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of the Nation’s forests and grasslands to meet the needs of present and future generations. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TTY). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Printed on recycled paper – September -

Songbird Ecology in Southwestern Ponderosa

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. Chapter 1 Ecology of Southwestern Ponderosa Pine Forests William H. Moir, Brian Geils, Mary Ann Benoit, and Dan Scurlock describes natural and human induced changes in the com- What Is Ponderosa Pine Forest position and structure of these forests. and Why Is It Important? Forests dominated by ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa Paleoecology var. scopulorurn) are a major forest type of western North America (figure 1; Steele 1988; Daubenmire 1978; Oliver and Ryker 1990). In this publication, a ponderosa pine The oldest remains of ponderosa pine in the Western forest has an overstory, regardless of successional stage, United States are 600,000 year old fossils found in west dominated by ponderosa pine. This definition corresponds central Nevada. Examination of pack rat middens in New to the interior ponderosa pine cover type of the Society of Mexico and Texas, shows that ponderosa pine was absent American Foresters (Eyre1980). At lower elevations in the during the Wisconsin period (about 10,400 to 43,000 years mountainous West, ponderosa pine forests are generally ago), although pinyon-juniper woodlands and mixed co- bordered by grasslands, pinyon-juniper woodlands, or nifer forests were extensive (Betancourt 1990). From the chaparral (shrublands). The ecotone may be wide or nar- late Pleistocene epoch (24,000 years ago) to the end of the row, and a ponderosa pine forest is recognized when the last ice age (about 10,400 years ago), the vegetation of the overstory contains at least 5 percent ponderosa pine (USFS Colorado Plateau moved southward or northward with 1986). -

A Conceptual Hydrogeologic Model for Fossil Springs, Western

A CONCEPTUAL HYDROGEOLOGIC MODEL FOR FOSSIL SPRINGS, WESTERN MOGOLLON RIM, ARIZONA: IMPLICATIONS FOR REGIONAL SPRINGS PROCESSES By L. Megan Green A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Geology Northern Arizona University May 2008 Approved: _________________________________ Abraham E. Springer, Ph.D., Chair _________________________________ Roderic A. Parnell, Jr., Ph.D. _________________________________ Paul J. Umhoefer, Ph.D. ABSTRACT A CONCEPTUAL HYDROGEOLOGIC MODEL FOR FOSSIL SPRINGS, WEST MOGOLLON MESA, ARIZONA: IMPLICATIONS FOR REGIONAL SPRINGS PROCESSES L. Megan Green Fossil Springs is the largest spring system discharging along the western Mogollon Rim in central Arizona and is a rare and important resource to the region. The purpose of this study was to gain a better understanding of the source of groundwater discharging at Fossil Springs. This was accomplished by (1) constructing a 3-D digital hydrogeologic framework model from available data to depict the subsurface geology of the western Mogollon Rim region and (2) by compiling and interpreting regional structural and geophysical data for Arizona’s central Transition Zone. EarthVision, a 3-D GIS modeling software, was used to construct the framework model. Two end-member models were created; the first was a simple interpolation of the data and the second was a result of geologic interpretations. The second model shows a monocline trending along the Diamond Rim fault. Both models show Fossil Springs discharging at the intersection of the Diamond Rim fault and Fossil Springs fault, at the contact between the Redwall Limestone and Naco Formation. The second objective of this study was a compilation of regional data for Arizona’s central Transition Zone.