AUC Kinanthrophologica 2 2015 4438.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Handbook Season 2021/22 Professional Development League Contents

Handbook Season 2021/22 Professional Development League Contents Club Information ....................................................................................................................02 Format .........................................................................................................................................11 Fixtures ........................................................................................................................................12 Rules of the Professional Development League ..................................................24 Professional Development League Club Information Club Information Barnsley Cardiff City Correspondence Address: Oakwell Stadium, Academy Manager: Bobby Hassell Correspondence Address: Cardiff City Academy Manager: James McCarthy Grove Street, Barnsley, S71 1ET Email: [email protected] Stadium, Leckwith Road, Cardiff, CF11 8AZ Email: [email protected] Tel: 01226 211211 Lead Coach: Martin Devaney Tel: 02920 643784 Lead Coach Steve Morison Email: [email protected] Tel: 01226 211211 Email: [email protected] Tel: 07525 709002 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Home Venue Address: Oakwell Training Administration: Jenny Pead Home Venue Address: Leckwith Stadium, Administration: Scott Dommett Ground, Grove Street, Barnsley, S71 1ET Position: Academy Secretary Leckwith Road, Cardiff, CF11 8AZ Position: Football Administrator Tel: 01226 211211 Tel: 02920 643784 Mobile: 07412 465922 -

Barbados Advocate

Established October 1895 See Inside Sunday April 25, 2021 $2 VAT Inclusive FAIR DEAL FOR Give more respect for intellectual property WRITERS! rights in Barbados Caddle: Sarah Ann Gill paved the By Cara L. Jean-Baptiste a license with The UWI Cave Hill start using the system in a way that Campus.” benefited them. However, that would way for other GOVERNMENT institutions are Additionally,he stated that there was mean that the Ministry of Education the biggest abusers of intellectual no respect for intellectual property in should look to use more books by local women to follow property and it is time for Barbados, because there were many writers for their scholastic programmes, something to be done about it. organisations in the country that were but this is not happening. Antonio ‘Boo’ Rudder, well-known using intellectual properties and were Furthermore, Rudder said: “Within – Page 2 musician and author, highlighted this as not paying royalties. recent times, there have been some he spoke during the National Cultural Because of this, Rudder believed that challenges in terms of fair dealings, Foundation’s (NCF) Beyond the Book it was important for writers to learn but the question is that fair dealing webinar. and understand the terms of copyright, can only be fair dealing if you are not “The Government is the biggest so that they could protect their work taking advantage of a piece of work or abuser of intellectual properties and no one would be able to use their exploiting the work to the writer’s in Barbados – the schools and the work without them being rewarded for detriment. -

Page Number: 1/22 May 22, 2017 at 01:45 PM

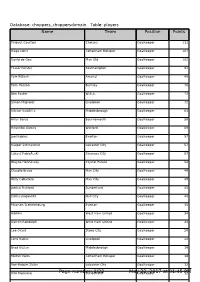

Database: choppers_choppersdomain, Table: players Name Name Team Team PositionPosition PointsPoints Thibaut Courtois Chelsea Goalkeeper 111 Hugo Lloris Tottenham Hotspur Goalkeeper 107 David de Gea Man Utd Goalkeeper 102 Fraser Forster Southampton Goalkeeper 91 Petr ÄŒech Arsenal Goalkeeper 88 Tom Heaton Burnley Goalkeeper 76 Ben Foster W.B.A. Goalkeeper 73 Simon Mignolet Liverpool Goalkeeper 72 VÃctor Valdés Middlesbrough Goalkeeper 63 Artur Boruc Bournemouth Goalkeeper 58 Heurelho Gomes Watford Goalkeeper 58 Joel Robles Everton Goalkeeper 57 Kasper Schmeichel Leicester City Goalkeeper 57 Lukasz FabiaÅ„ski Swansea City Goalkeeper 57 Wayne Hennessey Crystal Palace Goalkeeper 54 Claudio Bravo Man City Goalkeeper 49 Willy Caballero Man City Goalkeeper 49 Jordan Pickford Sunderland Goalkeeper 45 Eldin Jakupović Hull City Goalkeeper 40 Maarten Stekelenburg Everton Goalkeeper 35 Adrián West Ham United Goalkeeper 34 Darren Randolph West Ham United Goalkeeper 34 Lee Grant Stoke City Goalkeeper 28 Loris Karius Liverpool Goalkeeper 24 Brad Guzan Middlesbrough Goalkeeper 19 Michel Vorm Tottenham Hotspur Goalkeeper 16 Ron-Robert Zieler Leicester City Goalkeeper 12 Vito Mannone Page number:Sunderland 1/22 MayGoalkeeper 22, 2017 at 01:45 PM12 Database: choppers_choppersdomain, Table: players Name Name Team Team PositionPosition PointsPoints Jack Butland Stoke City Goalkeeper 11 Sergio Romero Man Utd Goalkeeper 10 Steve Mandanda Crystal Palace Goalkeeper 10 Adam Federici Bournemouth Goalkeeper 4 David Marshall Hull City Goalkeeper 3 Paul Robinson Burnley Goalkeeper 2 Kristoffer Nordfeldt Swansea City Goalkeeper 2 David Ospina Arsenal Goalkeeper 1 Asmir Begovic Chelsea Goalkeeper 1 Wojciech SzczÄ™sny Arsenal Goalkeeper 0 Alex McCarthy Southampton Goalkeeper 0 Allan McGregor Hull City Goalkeeper 0 Danny Ward Liverpool Goalkeeper 0 Joe Hart Man City Goalkeeper 0 Dimitrios Konstantopoulos Middlesbrough Goalkeeper 0 Paulo Gazzaniga Southampton Goalkeeper 0 Jakob Haugaard Stoke City Goalkeeper 0 Boaz Myhill W.B.A. -

West Brom Dig Deep to Win at Everton

SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 14, 2016 SPORTS Long sends soaring Southampton up to sixth They visit Tottenham Hotspur and Arsenal in their next two games. Unbeaten Swansea 0 in their previous four matches, Swansea fielded an unchanged side, with South Korea midfielder Ki Sung-Yueng returning to the bench after missing the 1-1 draw at Southampton 1 home to Crystal Palace with concussion. Southampton recalled four players, among them fit-again pair Matt Targett and Steven Davis, and procured an early sight SWANSEA: Shane Long struck as in-form of goal when Graziano Pelle shot straight at Southampton climbed to within one point Lukasz Fabianski from the edge of the box. of the Premier League’s European places Swansea replied with a tame Andre with a 1-0 victory at relegation-threatened Ayew effort, but the first half did not come Swansea City yesterday. to life until the verge of half-time, when the The Irishman nodded home a cross from teams exchanged good chances in the James Ward-Prowse in the 69th minute at space of a minute. First, Gylfi Sigurdsson the Liberty Stadium as Southampton volleyed over for Swansea from Alberto stretched their unbeaten run to six league Paloschi’s flick-on, before the unmarked games, during which time they have not Long headed straight at Fabianski at the conceded a single goal. other end. Pelle thought he had given It lifted Ronald Koeman’s side up to sixth Southampton the lead just before the hour place in the table, one point below fifth- when he turned the ball in after Fabianski place Manchester United and seven points had dropped it under pressure from Jose off the Champions League berths. -

Sapazovski the Hero As Gully Pays the Penalty

Australia’s Favourite Football Fanzine And Even Bigger In Sandringham! ? www.goalweekly.com $4 Season 5: Issue 13 Monday 25th May 2009 ? GEORGIES ? DERBY DAY Photo: Daniel Flis DELIGHT! SAPAZOVSKI THE HERO AS GULLY PAYS THE PENALTY SOUTH CELEBRATES FOOTBALL FOCUS ON JUBILEE ANNIVERSARY THUNDER’S COLIN QUIRK JUNIOR RESULTS / DUTCH MASTERS / VPL RD 12 FOOTBALL FAMILY FC Bush Fire Appeal Match - 2nd Leg VPL ALL-STARS SHINE VICTORIAN Premier League (VPL) Matthew Leckie had solid games. coach Chris Taylor has praised his “The midfi eld worked really hard team’s gutsy win over Melbourne all night... Osagie was always a Victory FC in the second leg of the threat; he showed last night he was Bushfi re Charity Appeal initiative. more than capable of playing A- The elite VPL combination League.” trounced the reigning A-League Taylor was reluctant to suggest champion 3-1 at Mansion Stadium, that the Victory would now look at an impressive effort given Taylor some of the VPL players for their was forced to fi eld a relatively inex- squad; however, he did say there perienced outfi t. would defi nitely be four or fi ve play- “We had limited preparation and ers considered by other A-League no chance to train,” Taylor said. teams. “Going down a goal and then com- The game, played at Mansion ing back showed a lot of character.” Stadium, was the second in a series Victory gained an early lead after organised by Football Federation Tom Pondeljak combined with Bra- Victoria to raise money for those af- zilian striker Ney Fabiano to score in fected by the Black Saturday bush- the fi rst half. -

2019 Panini Prizm Soccer Checklist

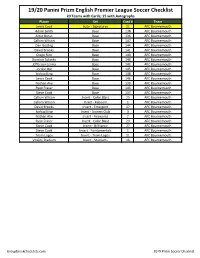

19/20 Panini Prizm English Premier League Soccer Checklist 20 Teams with Cards; 15 with Autographs Player Set Card # Team Lewis Cook Auto - Signatures 21 AFC Bournemouth Adam Smith Base 138 AFC Bournemouth Artur Boruc Base 136 AFC Bournemouth Callum Wilson Base 147 AFC Bournemouth Dan Gosling Base 144 AFC Bournemouth David Brooks Base 141 AFC Bournemouth Diego Rico Base 140 AFC Bournemouth Dominic Solanke Base 149 AFC Bournemouth Jefferson Lerma Base 142 AFC Bournemouth Jordon Ibe Base 145 AFC Bournemouth Joshua King Base 148 AFC Bournemouth Lewis Cook Base 146 AFC Bournemouth Nathan Ake Base 139 AFC Bournemouth Ryan Fraser Base 143 AFC Bournemouth Steve Cook Base 137 AFC Bournemouth Callum Wilson Insert - Color Blast 25 AFC Bournemouth Callum Wilson Insert - Kaboom 1 AFC Bournemouth David Brooks Insert - Emergent 17 AFC Bournemouth Joshua King Insert - Scorers Club 3 AFC Bournemouth Nathan Ake Insert - Fireworks 7 AFC Bournemouth Ryan Fraser Insert - Color Blast 23 AFC Bournemouth Steve Cook Insert - Brilliance 27 AFC Bournemouth Steve Cook Insert - Fundamentals 1 AFC Bournemouth Team Logos Insert - Team Logos 11 AFC Bournemouth Vitality Stadium Insert - Stadiums 16 AFC Bournemouth Groupbreakchecklists.com 2019 Prizm Soccer Checklist Diego Rico Base 140 AFC Bournemouth David Seaman Auto - Flashback 5 Arsenal Dennis Bergkamp Auto - Club Legends Signatures 3 Arsenal Dennis Bergkamp Auto - Dual Player Signatures 3 Arsenal Freddie Ljungberg Auto - Club Legends Signatures 6 Arsenal Robert Pires Auto - Flashback 9 Arsenal Robin van Persie -

Page 01 Jan 17.Indd

www.thepeninsulaqatar.com BUSINESSB | 21 SPORT | 36 AIIB to boost Dakar dozen for regional Peterhansel, Al ininvestments: Xi Attiyah second SUNDAY 17 JANUARY 2016 • 7 Rabia II 1437 • Volume 20 • Number 6678 thepeninsulaqatar @peninsulaqatar @peninsula_qatar OPINION Microchips in vehicles to curb Dr. Khalid Al-Shafi fuel bill fraud Acting Editor-in-Chief The hateful lesion vehicle such as its registration number, name and location of petrol station of terrorism Woqod’s new system (where a customer prefers refuelling), designed to eliminate date, time and other details as desired. errorist blasts and oper- “It’s a very smart and convenient ations are increasing day cash transactions system that we have introduced. It Tafter day affecting dif- will provide full control to custom- ferent places and threatening ers about the details such as accurate lives of individuals and soci- bill, amount purchased etcetera. It eties. Unfor tunately, they are By Mohammad Shoeb works at all our gas stations. It will being committed by indi- The Peninsula also help reduce refuelling time,” viduals and groups calling Yousef Al Sulaiti, Manager, Infor- Portraits of Emir H H Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani and Father Emir H H Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al themselves Islamic groups mation Technology at Woqod, told Thani on a building of the Sheikh Hamad Residential City in the southern Gaza Strip town of Khan Younis whereas Islam preaches reporters. yesterday. peace. The prevalence of DOHA: To check any possible wrong- Al Sulaiti said that the system is this phenomenon is linked doings such as issuing of inflated bills going to bring a significant change in to political developments and by petrol station staff or fraudulent the experience of motorists at Woqod deterioration of conditions in acts by some consumers, Qatar Fuel fuel stations. -

Uefa Europa League 2012/13 Season Match Press Kit

UEFA EUROPA LEAGUE 2012/13 SEASON MATCH PRESS KIT FC Metalist Kharkiv (first leg: 0-0) Newcastle United FC Matchday 8 - Round of 32, second leg Metalist Stadium, Kharkiv Thursday 21 February 2013 19.00CET (20.00 local time) Contents Previous meetings.............................................................................................................2 Match background.............................................................................................................3 Team facts.........................................................................................................................4 Squad list...........................................................................................................................6 Fixtures and results...........................................................................................................8 Match-by-match lineups..................................................................................................12 Match officials..................................................................................................................15 Legend............................................................................................................................16 This press kit includes information relating to this UEFA Europa League match. For more detailed factual information, and in-depth competition statistics, please refer to the matchweek press kit, which can be downloaded at: http://www.uefa.com/uefa/mediaservices/presskits/index.html FC -

Análise Dinâmica De Redes Em Futebol: Contributo Para a Determinação Da Influência Individual No Desempenho Coletivo

UNIVERSIDADE TÉCNICA DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE MOTRICIDADE HUMANA Análise dinâmica de redes em futebol: Contributo para a determinação da influência individual no desempenho coletivo Dissertação apresentada com vista à obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Treino de Alto Rendimento Orientador: Professor Doutor Ricardo Filipe Lima Duarte Coorientador: Professor Doutor Fernando Paulo de Oliveira Gomes Júri Presidente Professor Doutor Pedro José Madaleno Passos Vogais Professor Doutor Fernando Paulo de Oliveira Gomes Professor Doutor Ricardo Filipe Lima Duarte Professor Doutor Luís Pedro Camelo Vilar Vitor José Jorge Pereira Julho 2015 Declaração de Reprodução da Dissertação Nome: Vitor José Jorge Pereira Endereço eletrónico. [email protected] Telefone: 265497314 Número do Cartão de Cidadão: 10122046 4zz2 Título: Análise dinâmica de redes em futebol: Contributo para a determinação da influência individual no desempenho coletivo. Orientador: Ricardo Filipe Lima Duarte Co-Orientador: Fernando Paulo de Oliveira Gomes Ano de conclusão: 2015 Mestrado: Treino de Alto Rendimento É autorizada a reprodução integral desta tese/trabalho apenas para efeitos de investigação, mediante declaração escrita do interessado, que a tal se compromete. Faculdade de Motricidade Humana – Universidade de Lisboa Cruz Quebrada, 26/ 06 / 2015 Assinatura______________________________________________________________ Agradecimentos À semelhança da performance individual dos jogadores de futebol, também o desenvolvimento deste trabalho teve momentos altos e baixos. Olhando para trás, percebo agora um pouco melhor que todos foram importantes, pois se os primeiros serviram de incentivo para prosseguir em frente, os segundos constituíram pontos de mudança numa rota que não se antevia certa. Felizmente, neste percurso tive o privilégio de contar com o permanente apoio de algumas pessoas, às quais gostaria de expressar o meu sincero reconhecimento e agradecimento: Ao Professor Doutor Ricardo Duarte, pela visão, rigor e disponibilidade permanente ao longo da realização do trabalho. -

Soccercardindex.Com Merlin’S Premier Stars 2006

soccercardindex.com Merlin’s Premier Stars 2006 1 Premier League Trophy Bolton Fulham Middlesbrough Tottenham 2 Chelsea - 49 Jussi Jaaskelainen 93 Mark Crossley 137 Mark Schwarzer 181 Paul Robinson Champions 04/05 50 Radhi Jaidi 94 Moritz Volz 138 Stuart Parnaby 182 Ledley King 3 Thierry Henry – Arsenal 51 Bruno N'Gotty 95 Zat Knight 139 Ugo Ehiogu 183 Michael Dawson Topscorer 2004/05 52 Ivan Campo 96 Alain Goma 140 Gareth Southgate 184 Teemu Tainio 4 Frank Lampard – Chelsea 53 Nicky Hunt 97 Niclas Jensen 141 Franck Queudrue 185 Edgar Davids Player of the Year 04/05 54 Gary Speed 98 Steed Malbranque 142 Gaizka Mendieta 186 Michael Carrick 55 Kevin Nolan 99 Claus Jensen 143 George Boateng 187 Andy Reid Arsenal 56 Jay-Jay Okocha 100 Ahmad Elrich 144 Stewart Downing 188 Reto Ziegler 5 Jens Lehmann 57 Ricardo Gardner 101 Luis Boa Morte 145 Mark Viduka 189 Wayne Routledge 6 Lauren 58 El-Hadji Diouf 102 Heidar Helguson 146 Aiyegbeni Yakubu 190 Hossam Ahmed Mido 7 Kolo Toure 59 Kevin Davies 103 Brian McBride 147 Jimmy Floyd Hasselbaink 191 Jermain Defoe 8 Ashley Cole 9 Alexander Hleb Charlton Liverpool Newcastle West Bromwich 10 Fredrik Ljungberg 60 Stephan Andersen 104 José Reina 148 Shay Given 192 Chris Kirkland 11 Philippe Senderos 61 Luke Young 105 John Arne Riise 149 Celestine Babayaro 193 Neil Clement 12 Francesc Fabregas 62 Hermann Hreidarsson 106 Jamie Carragher 150 Jean-Alain Boumsong 194 Paul Robinson 13 Thierry Henry 63 Chris Perry 107 Sami Hyypia 151 Titus Bramble -

Tharunka 2014

Week 11 - Week 12, Semester 2, 2014 First Published 1953 Volume 60, No. 13 University of NSW’s Independent Student Newspaper 2 EDITORIAL Editors’ Letter Hey Folks, Another semester drawing to a close, another Tharunka full of good stuff. Enjoy Issue 13! It's packed to the brim of the usual great news articles, reviews, satire, sports, and zero SRC election coverage (sorry - some red tape means we can't report on the elections this year.) Goodluck this week. xoxo Ammy and Freya, with Tina. Editors: Ammy Singh, Freya King Tharunka acknowledges the Be- team, unless expressly stated. Arc Acting Editor: Tina Giannoulis degal and Gadigal people, the tra- accepts no responsibility for the ac- Copy Editor: Araz Eleyasian ditional custodians of the land on curacy of any of the opinions or in- Design: Chere De Koh which the University stands. formation contained in this issue of Comic illustrations: Dom Foffani, Tharunka is published periodically Paden Hunter Tharunka. Any complaints should by Arc @ UNSW. The views ex- be made in writing to the Market- Contact: pressed herein are not necessarily ing & Publications Coordinator. [email protected] the views of Arc, the Representative PO Box 173, Kingsford, NSW, 2032 Council or the Tharunka editing EDITORIAL 3 Calendar Tuesday 14 October: Volunteer Expo + SRC BBQ Main Library Walkway from 11am to 2pm What happens in caucus, stays in caucus… Been thinking about giving back? Keen to get experience with some of the best volunteer pro- grams out? Unsure where to start? Then stop in on your way to a study sesh for all the info you except in Labor Left could want as well as a barbeque to keep you going! Who is leaking unredacted minutes from UNSW Labor Left Stu- Anti-Poverty Week Trivia Night dents’ (LLS) caucus meetings to their traditional rivals over in UNSW Beer Garden, Roundhouse at 5pm Labor Right, a.k.a. -

Gaia Raising the Bar

Established October 1895 See Inside Monday January 18, 2016 $1 VAT Inclusive GAIA RAISING THE BAR THE Grantley Adams International His comments came during the GAIA People and our competitors, both at the port without the Civil Aviation Airport Inc (GAIA) is going through Inc’s 10th anniversary Awards Dinner national level and industry level, which Department, Customs, Immigration, and a process of change, to provide a held at the Lloyd Erskine Sandiford are other airports, are reinventing them- RBPF [Royal Barbados Police Force]. better product to those who utilise Centre on Saturday night under the selves. And the visitor that comes to Barbados its services and to remain competi- theme:“Reculturalisation: Changing the “We are trying to reculturalise by de- and the Barbadians that return home tive. Way we Do Business.” partment. We are trying to reculturalise are not interested in what department So says Chief Executive Officer of According to Barrow: “The slogan of the whole company that we rise higher you work for, they are interested in the GAIA Inc., David Barrow,who also stated the airport is Rising Higher. We have from the point at which we did the work- service that you provide to them,” he that partnerships with all the entities done pretty well in the last ten years, but shops, to provide a better service, a bet- stated. working at the airport will be key to the the fact is that the industry in which we ter product and in conjunction with our enhancement of the services offered. find ourselves is not a static industry.