Observations: a Student Publication of the Lemke Journalism De

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Installation Explores the Final Girl Trope. Final Girls Are Used in Horror Movies, Most Commonly Within the Slasher Subgenre

This installation explores the final girl trope. Final girls are used in horror movies, most commonly within the slasher subgenre. The final girl archetype refers to a single surviving female after a murderer kills off the other significant characters. In my research, I focused on the five most iconic final girls, Sally Hardesty from A Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Laurie Strode from Halloween, Ellen Ripley from Alien, Nancy Thompson from A Nightmare on Elm Street and Sidney Prescott from Scream. These characters are the epitome of the archetype and with each girl, the trope evolved further into a multilayered social commentary. While the four girls following Sally added to the power of the trope, the significant majority of subsequent reproductions featured surface level final girls which took value away from the archetype as a whole. As a commentary on this devolution, I altered the plates five times, distorting the image more and more, with the fifth print being almost unrecognizable, in the same way that final girls have become. Chloe S. New Jersey Blood, Tits, and Screams: The Final Girl And Gender In Slasher Films Chloe S. Many critics would credit Hitchcock’s 1960 film Psycho with creating the genre but the golden age of slasher films did not occur until the 70s and the 80s1. As slasher movies became ubiquitous within teen movie culture, film critics began questioning why audiences, specifically young ones, would seek out the high levels of violence that characterized the genre.2 The taboo nature of violence sparked a powerful debate amongst film critics3, but the most popular, and arguably the most interesting explanation was that slasher movies gave the audience something that no other genre was able to offer: the satisfaction of unconscious psychological forces that we must repress in order to “function ‘properly’ in society”. -

It up on Valentine ^

STUDENTS RAISE MONEY FOR THE HEART AND STROKE FOUNDATION it up on Valentine ^ VALENTINE'S DAY FORMAL: (L-R) Carolyn Valade, Amber Walsh, Andrea Berkuta, Elizabeth Simmonds, Crystal Wood, Teri Stewart, Karyn Gottschalk, and Susan Davies make a conga line at a party put on by Durham College students who live In residence. Money raised went to help support the Heart and Stroke Foundation. See VALENTINE'S pg. 14 - 15 Pholo by Fannio Sunshine tl'si^aliStii^^ Mayor supports a university-college l^n^t^sBsw^on^^w^^s^^f^.^^^ ^Pogal^ BY DEBBIE BOURKE Chronicle staff community's support, the college will be sending a pro- posal to the government in June and is hoping to get Oshawa city councillors are supporting Durham legislative approval by November. College's campaign to convince the provincial govern- Diamond said it is time to collectively endorse a uni- ment to pass legislation that would con- versity-college. vert the college to a university-college. "The moment is now because the During a city council meeting on Feb. province is working with a SuperBuild 7, Mayor Nancy Diamond said a univer- " We should have fund," she said. "And the minister stat- sity would boost Oshawa's economy had a university ed that tlie money would be allotted for and provide an opportunity for young roads, health care, and colleges and uni- people in Durham Region. in the '60s . all versities." The university-college would keep its I'm saying is now Diamond added that the college college programs and offer university- already sits on about 160 acres of land, so P. -

Spartan Daily (October 5, 2011)

Happiness does not come with a price tag Opinion p. 5 See online: Wednesday SPARTAN DAILY LibraryLib evacuated October 5, 2011 Hornets swarm Spartans Sports p. 4 Volume 137, Issue 21 SpartanDaily.com Increasing SJ gang A Clean Slate activity prompts UPD campus alert Over the past 18 months, San Jose has Crimes increase south of seen a spike in gang activity. campus; police cite regular “There have always been spikes in gang activities,” Sgt. Manuel fluctuation in frequency Aguayo of the UPD said. “It’s a generational thing … it's cyclical.” by Chris Marian Staff Writer Homicides per 3.5 100,000 people per year On the night of Saturday, Sept. 24, in San Jose residents of the 500 block of South 3.0 All homicides 10th Street awoke to the sounds of gunfi re ringing out into the night, as 2.5 police said rival gangs clashed once 2.0 more for territory and respect in the neighborhoods southwest of the SJSU 1.5 campus. Gang-related Police arriving on the scene se- 1.0 cured one wounded suspect and cap- homicides 0.5 tured another — the rest fl ed south 20062007 2008 2009 2010 Dulce Alvarez, a San Jose Conservation Corps intern, The Conservation Corp has been working with the with a San Jose Police Department dumps recyclables into a bin on Wednesday, Sept. 28 City of San Jose to advance its zero-waste policy. SWAT team on their heels, according 80 Gang-related crimes per outside of Clark Hall. Alvarez has been working as a The corps has been in existence since 1987. -

Sob Sisters: the Image of the Female Journalist in Popular Culture

SOB SISTERS: THE IMAGE OF THE FEMALE JOURNALIST IN POPULAR CULTURE By Joe Saltzman Director, Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture (IJPC) Joe Saltzman 2003 The Image of the Female Journalist in Popular Culture revolves around a dichotomy never quite resolved. The female journalist faces an ongoing dilemma: How to incorporate the masculine traits of journalism essential for success – being aggressive, self-reliant, curious, tough, ambitious, cynical, cocky, unsympathetic – while still being the woman society would like her to be – compassionate, caring, loving, maternal, sympathetic. Female reporters and editors in fiction have fought to overcome this central contradiction throughout the 20th century and are still fighting the battle today. Not much early fiction featured newswomen. Before 1880, there were few newspaperwomen and only about five novels written about them.1 Some real-life newswomen were well known – Margaret Fuller, Nelly Bly (Elizabeth Cochrane), Annie Laurie (Winifred Sweet or Winifred Black), Jennie June (Jane Cunningham Croly) – but most female journalists were not permitted to write on important topics. Front-page assignments, politics, finance and sports were not usually given to women. Top newsroom positions were for men only. Novels and short stories of Victorian America offered the prejudices of the day: Newspaper work, like most work outside the home, was for men only. Women were supposed to marry, have children and stay home. To become a journalist, women had to have a good excuse – perhaps a dead husband and starving children. Those who did write articles from home kept it to themselves. Few admitted they wrote for a living. Women who tried to have both marriage and a career flirted with disaster.2 The professional woman of the period was usually educated, single, and middle or upper class. -

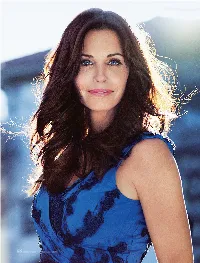

Download Ebook ~ the Courteney Cox Handbook

AK3NQU6LZRTJ » Kindle // The Courteney Cox Handbook - Everything you need to know about Courteney... Th e Courteney Cox Handbook - Everyth ing you need to know about Courteney Cox Filesize: 6.82 MB Reviews A really awesome ebook with perfect and lucid reasons. Indeed, it is engage in, still an amazing and interesting literature. I am just very easily could possibly get a satisfaction of reading a composed publication. (Petra Kuphal) DISCLAIMER | DMCA 7SLYKHJ8JPUL \\ Doc # The Courteney Cox Handbook - Everything you need to know about Courteney... THE COURTENEY COX HANDBOOK - EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT COURTENEY COX To download The Courteney Cox Handbook - Everything you need to know about Courteney Cox PDF, you should refer to the hyperlink under and download the ebook or get access to additional information that are in conjuction with THE COURTENEY COX HANDBOOK - EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT COURTENEY COX book. tebbo. Paperback. Book Condition: New. Paperback. 192 pages. Dimensions: 11.6in. x 8.3in. x 0.4in.Courteney Bass Cox (born June 15, 1964) is an American actress best known for her roles as Monica Geller on the NBC sitcom Friends, Gale Weathers in the horror series Scream, and as Jules Cobb in the ABC sitcom Cougar Town, for which she earned her first Golden Globe nomination. Cox has also starred in Dirt produced by Coquette Productions, a production company created by herself and husband David Arquette. This book is your ultimate resource for Courteney Cox. Here you will find the most up-to-date information, photos, and much more. In easy to read chapters, with extensive references and links to get you to know all there is to know about her Early life, Career and Personal life right away. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Scream a Screenplay by Kevin Williamson Unsubs Central

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Scream A Screenplay by Kevin Williamson UnSubs Central. Your stop for killer book and film reviews about the world's most notorious serial murderers. Scream 4: Calling Kevin Williamson. In 2014, I came across an opportunity to write for an arts & entertainment website. To apply, all I had to do was write a film review. I had never written a film review. After a flurry of research on “How to Write a Film Review,” next was deciding the film. I did not have to think long. I would review Scream 4 . I had an encyclopedic knowledge of the Scream series and had lost count of how many times I had watched and rewatched. I considered Wes Craven one of my heroes. The topper? Scream 4 had filmed in my town and many a late night was spent sitting on a sidewalk across the street watching them film. Yes, I would review Scream 4 . Below is my review as sent to the editor in 2014. Spoiler alert – I got the gig and for three years was a blogger for The Script Lab. Happy reading! Dimension Films – 2011 Director: Wes Craven Screenplay: Kevin Williamson, Ehren Kruger (not credited) Scream 4: Calling Kevin Williamson, Calling Kevin Williamson by Michelle Donnelly. With fevered anticipation I arrive at the movie theater on opening night to see Scream 4 , the latest installment of the Scream series. An hour and fifty-one minutes later, I walk out wondering what I have done to drive screenwriter Kevin Williamson away and am confused as to why he wants to destroy the relationship we once had. -

The Final Girl Grown Up: Representations of Women in Horror Films from 1978-2016

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2017 The inF al Girl Grown Up: Representations of Women in Horror Films from 1978-2016 Lauren Cupp Scripps College Recommended Citation Cupp, Lauren, "The inF al Girl Grown Up: Representations of Women in Horror Films from 1978-2016" (2017). Scripps Senior Theses. 958. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/958 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FINAL GIRL GROWN UP: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN IN HORROR FILMS FROM 1978-2016 by LAUREN J. CUPP SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR TRAN PROFESSOR MACKO DECEMBER 9, 2016 Cupp 2 I was a highly sensitive kid growing up. I was terrified of any horror movie I saw in the video store, I refused to dress up as anything but a Disney princess for Halloween, and to this day I hate haunted houses. I never took an interest in horror until I took a class abroad in London about horror films, and what peaked my interest is that horror is much more than a few cheap jump scares in a ghost movie. Horror films serve as an exploration into our deepest physical and psychological fears and boundaries, not only on a personal level, but also within our culture. Of course cultures shift focus depending on the decade, and horror films in the United States in particular reflect this change, whether the monsters were ghosts, vampires, zombies, or aliens. -

David Arquette Will Return to Pursue Ghostface As Dewey Riley in the Relaunch of Scream for Spyglass Media Group

DAVID ARQUETTE WILL RETURN TO PURSUE GHOSTFACE AS DEWEY RILEY IN THE RELAUNCH OF SCREAM FOR SPYGLASS MEDIA GROUP James Vanderbilt and Guy Busick to Co-write the Screenplay With Project X Entertainment Producing, Creator Kevin Williamson Serving as Executive Producer and the Filmmaking Collective Radio Silence at the Helm LOS ANGELES (May 18, 2020)— David Arquette will reprise his role as Dewey Riley in pursuit of Ghostface in the relaunch of “Scream,” it was announced today by Peter Oillataguerre, President of Production for Spyglass Media Group, LLC (“Spyglass”). Plot details are under wraps but the film will be an original story co-written by James Vanderbilt (“Murder Mystery,” “Zodiac,” “The Amazing Spider-Man”) and Guy Busick (“Ready or Not,” “Castle Rock,”) with Project X Entertainment’s Vanderbilt, Paul Neinstein and William Sherak producing for Spyglass. Creator Kevin Williamson will serve as executive producer. Matt Bettinelli- Olpin and Tyler Gillett of the filmmaking group Radio Silence (“Ready or Not,” “V/H/S”) will direct and the third member of the Radio Silence trio, Chad Villella, will executive produce alongside Williamson. Principal photography will begin later this year in Wilmington, North Carolina when safety protocols are in place. Arquette said, “I am thrilled to be playing Dewey again and to reunite with my ‘Scream’ family, old and new. ‘Scream’ has been such a big part of my life, and for both the fans and myself, I look forward to honoring Wes Craven’s legacy.” Though Arquette is the first member of the film’s ensemble to be officially announced, conversations are underway with other legacy cast. -

66 More.Com | February 2014 Blipp This Page to See—And Hear—Cox Behind the Scenes of the More Shoot

CCC 66 more.com | february 2014 BLIPP THIS PAGE to see—and hear—Cox behind the scenes of the More shoot. CC WELCOME TO TOWN IT’S A PLACECourteney WHERE DIVORCE CAN BE AMICABLE, WORK IS COLLABORATIVE AND FRIENDSHIPS ARE LIFELONG. HOW COURTENEY COX, THE INSPIRINGLY GROUNDED STAR OF COUGAR TOWN, CULTIVATES C CLOSENESS BOTH ONSCREEN AND OFF | BY MARGOT DOUGHERTY PHOTOGRAPHED BY SIMON EMMEtt STYLED BY JONNY LICHTENSTEIN seeming utterly relaxed as she or- “I think he got the idea that I’m not a ders a glass of Cabernet. pain in the ass and am actually fun to Cox is currently entertaining audi- work with.” Shortly thereafter, Law- ences on Cougar Town, the TBS sitcom rence invited Cox and Coquette, the she stars in, produces and occasion- production company she owns with ally directs. Her character, Jules, is her ex-husband, David Arquette, onto the leader of a pack of friends who live the Cougar Town bus. on a Florida cul-de-sac. She began the To create Jules, Lawrence spent show as the recently divorced mother time observing Cox, attending the of an 18-year-old, dating again after Sunday-night dinners she has hosted 20 years of marriage. Now, five sea- for friends and family for about 25 C sons in, Jules is married to her former years. “He was getting to know the neighbor and surrounded by hilari- weird parts of me that he could write ous, idiosyncratic sidekicks played about,” she says. “He said he came to by, among others, Busy Philipps and my house one time and I poured the Christa Miller, whose husband, Bill wineglass so full, he could barely walk COURTENEY COX makes an unexpected Lawrence, is the show’s cocreator. -

Soafty "10V1t

~- \ SOAftY "10V1t ft1:W~lT1: JU\.Y iSl, 1996 ltC1SmtR: WCAW ( FADE IN ON A RINGINGTELEPHONE. A hand reaches for it, bringing the receiver up to the face of CASEY BECKER, a young girl, no more than sixteen. A friendly face with innocent eyes. CASEY Hello. MAN'S VOICE (from phone) Bello. Silence. CASEY Yes? MAN Who is this? CASEY Who are you trying to reach? MAN What number is this? CASEY What number are you trying to reach? MAN I don't know. CASEY I think you have the wrong number. MAN Do I? CASEY It happens. Take it easy. CLICK 1 She bangs up the phone. The CAMERA PULLS BACK to reveal Casey in a living room, alone. She moves from the living room to the kitchen. It's a nice house. Affluent. The phone RINGS again. ~ -::::. l. =···-: 2. INT. KITCHEN /, ,•,. ,. Casey grabs the portable • CASEY Hello. MAN I'm sorry. I guess I dialed the wrong number. CASEY So why did you dial it again? MAN To apologize. CASEY You' re forgiven. Bye now. MAN Wait, wait, don't bang up. Casey stands in front of a sliding glass door. It's pitch black outside. CASEY What? MAN I want to talk to you for a second. CASEY They've got 900 numbers for that. Seeya. CLICKl Casey hangs up. A grin on ber face. EXT. CASEY'S HOUSE- NIGB'l' - ESTABLISHING A big, country home with a huge sprawling lawn full of big oak trees. It sits alone with no neighbors in sight. The phone RINGS again. -

Sherron Kean 056406 Edits Logo SHERRON

Blood, Guts and Becoming: The Evolution of the Final Girl. Sherron Kean, B.A. (Hons). Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy. University of Tasmania May, 2016. "This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright.” 11/05/2016 This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying and communication in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. 11/05/2016 ii Acknowledgments Thank you to my supervisor, Imelda Whelehan, for all her help and support, this certainly wouldn’t have been what it is without you. Also thank you for our weekly meetings and our chats about movies. My sincere gratitude and many thanks to Tony Simoes da Silva for his ongoing support and assistance throughout the everlasting editing process. My sincere thanks and appreciation to my mum, Kath, for listening and talking through every single idea I had. Also for sitting through countless horror films, even the ones that weren’t very enjoyable. Also, a thank you and deep appreciation to my ever-supportive partner who has been through this with me and who has read countless drafts and taken part in numerous conversations about this endeavour. -

I. My Favourite Film – Review of Three Films

Assignments 9ab e2 BE-20-04-27 I. My favourite film – review of three films Read these reviews of three old videos. Daylight (1996) Rob Cohen’s film is an old-fashioned1 disaster movie2. It stars3 Sylvester Stallone as an ordinary person who saves the day when a group of people get stuck4 in the road tunnel between Manhattan and New Jersey. The film isn’t too scary because you know exactly what is going to happen next. I found it fun to guess what was going to happen next. I was usually right! I’ve seen it all before in the old disaster movies but I still enjoyed it. Titanic (1998) James Cameron’s film starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet broke all records to become the most successful film in cinema history. The film, which cost $200 million to make, tells the tragic story of how at 11.40 pm on Sunday April 14, 1912, the passenger ship the Titanic crashed into an iceberg on its first journey from Southampton to New York and sank in the icy waters of the Atlantic two hours later. The film uses a lot of real events but Cameron chose to make the love story between Jack and Rose the centre of the film. It’s romantic and full of tragedy. Scream 2 This scary film stars Neve Campbell and Courteney Cox. It’s an old film but is sure to give you the shivers5. This is the story: Sidney Prescott (Neve Campbell) has finally got over6 her experience in Scream 1 and is about to start college with her boyfriend Derek.