The Steering Committee on the Environment and Forests Sector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Create Your Own Environmental Emphasis

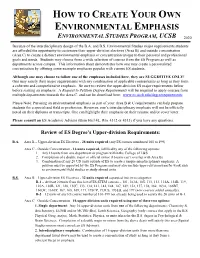

HOW TO CREATE YOUR OWN ENVIRONMENTAL EMPHASIS 2019 ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES PROGRAM, UCSB 2020 Because of the interdisciplinary design of the B.A. and B.S. Environmental Studies major requirements students are afforded the opportunity to customize their upper-division electives (Area B) and outside concentration (Area C) to create a distinct environmental emphasis or concentration unique to their personal and professional goals and needs. Students may choose from a wide selection of courses from the ES Program as well as departments across campus. This information sheet demonstrates how one may create a personalized concentration by offering some example emphases popular with current ES students. Although one may choose to follow one of the emphases included here, they are SUGGESTIVE ONLY! One may satisfy their major requirements with any combination of applicable courses/units as long as they form a coherent and comprehensive emphasis. Be sure to review the upper-division ES major requirements below before starting an emphasis. A Request to Petition Degree Requirements will be required to apply courses from multiple departments towards the Area C, and can be download here: www.es.ucsb.edu/degreerequirements Please Note: Pursuing an environmental emphasis as part of your Area B & C requirements can help prepare students for a specialized field or profession. However, one’s interdisciplinary emphasis will not be officially noted on their diploma or transcripts. One can highlight their emphasis on their resume and/or cover letter. Please consult an ES Academic Advisor (Bren Hall 4L, Rm. 4312 or 4313) if you have any questions. Review of ES Degree’s Upper-division Requirements: B.A. -

Issues in Environmental Science and Technology

ISSUES IN ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY EDITORS: R. E. HESTER AND R. M. HARRISON 12 ROYAL SOCIETY OF CHEMISTRY ISBN 0-85404-255-5 ISSN 1350-7583 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library @ The Royal Society of Chemistry 1999 All rights reserved Apart from any lair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review as permitted under the terms of the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, this publication may not be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of The Royal Societ}' of Chemistry, or in the case ofreprographic reproduction only in accordance with the terms of the licence.~ issued b}' the Cop}Tight Licensing Agenc}' in the UK, or in accordance Ilith the terms of the licences issued by the appropriate Reproduction Rights Organization outside the UK. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the terms stated here should be sent to The Royal Society of Chemistry at the addre.~.~ printed on this page. Published by The Royal Society of Chemistry, Thomas Graham House, Science Park, Milton Road, Cambridge CB4 OWF, UK For further information see our web site,at www.rsc.org Typeset in Great Britain by Vision Typesetting, Manchester Printed and bound by Redwood Books Ltd., Trowbridge, Wiltshire Editors Ronald E. Hester, BSc, DSc(London), PhD(Cornell), FRSC, CChem Ronald E. Rester is Professor of Chemistry in the University of York. He was for short periods a research fellow in Cam bridge and an assistant professor at Cornell before being appointed to a lectureship in chemistry in Y orkin 1965. -

Ecological and Environmental Chemistry

CHEMISTRY JOURNAL OF MOLDOVA. General, Industrial and Ecological Chemistry. 2017, 12(1), 9-19 ISSN (p) 1857-1727 ISSN (e) 2345-1688 http://cjm.asm.md http://dx.doi.org/10.19261/cjm.2017.427 ECOLOGICAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL CHEMISTRY Nowadays, our human civilization existing of industrial and humanitarian aspects of life, to on Earth faces a series of top importance defend against the cosmic threats, etc. People challenges that represent direct impact on its have to harmonize their relations with nature, to existence and development, both industrial and ensure the long-term and sustainable life of their social. All the natural compartments and their civilization, under conditions of rapid changes in components are subjected to the strong and technology, sciences, social life, natural processes unprecedented anthropogenic influence, including and permanently emerging challenges. lithosphere, soil, surface and ocean water, In the previous years of progressively atmosphere, vegetal and animal world. increasing industrial development (XVIII - Anthropogenic activities has reached such high mid-XX centuries), practically no attention was proportions that provoke the changes in the paid to the danger of deliberated interference of energy (heat) balance of certain regions and man into the material processes occurring on the planet as a whole that can affect the climate, planet. Along the decades, the scientists increase of water level in oceans and seas, considered the nature possessing the unlimited flooding of large areas. capacity to compensate the anthropogenic Almost, all the ecosystems and natural impacts. However, even centuries ago, the facts of compartments are affected by the anthropogenic irreversible changes in environment as a result of pollution. -

Smoke and Mirrors Are Not the Solu- Tion to Global Warming Alan Robock (Rutgers University, [email protected])

Royal Society of Chemistry—Environmental Chemistry Group—Bulletin—July 2016 19 DGL Article Smoke and mirrors are not the solu- tion to global warming Alan Robock (Rutgers University, [email protected]) Geoengineering is the “deliberate large- scale manipulation of the planetary environment to counteract anthropogenic climate change” (1). Proposed schemes include carbon dioxide reduction (CDR) and radiation management (RM). CDR technology exists but is very expensive, and no facilities exist for doing it on a large scale. It presents very different engineering, scientific, governance, and ethical issues than RM. Here I focus on the most studied proposed RM scheme, artificial creation of stratospheric aerosol clouds. I use the term “geoengineering” to refer to that scheme (2). Geoengineering is currently impossible. The technology does not exist, and there are serious questions as to whether it would be possible to create a cloud in the stratosphere that would have the desired effects. We can investigate the impacts of a geoengineering intervention Figure 1. Proposed methods of stratospheric aerosol by using analogues, in particular volcanic eruptions, to injection. A mountain top location would require less explore some of the resulting benefits and risks. We can energy for lofting to stratosphere. Drawing by Brian also use climate models, that is, computer simulations West. Reprinted with permission from (5). that calculate the climate response to geoengineering scenarios. These are the same models that we use for African summer monsoons, reducing precipitation to the weather forecasting and global warming climate food supply for billions of people; ozone depletion; no simulations. They are validated with simulations of past more blue skies; reduction of solar power; and rapid climate, in particular the response to volcanic eruptions. -

Green Chemistry

Green Chemistry View Article Online PERSPECTIVE View Journal | View Issue Education in green chemistry and in sustainable chemistry: perspectives towards sustainability Cite this: Green Chem., 2021, 23, 1594 Vânia G. Zuin, *a,b,c Ingo Eilks, d Myriam Elschami c,e and Klaus Kümmerer c,e Innovation in green and sustainable technologies requires highly qualified professionals, who have critical, inter/transdisciplinary and system thinking mindsets. In this context, green chemistry education (GCE) and sustainable chemistry education (SCE) have received increasing attention, especially in recent years. However, gaps remain in further understanding the historical roots of green chemistry (GC) and sustain- able chemistry (SC), their differences, similarities, as well the implications of this wider comprehension into curricula. Building on existing initiatives, further efforts are needed at all levels to mainstream GCE and SCE into chemistry and other education curricula and teaching, including gathering and disseminating best practices and forging new and strengthened partnerships at the national, regional and global levels. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. Received 1st October 2020, The latest perspectives for education and capacity building on GC and towards SC will be presented, Accepted 22nd January 2021 demonstrating their crucial role to transform human resources, institutional and infrastructural settings in DOI: 10.1039/d0gc03313h all sectors on a large scale, to generate effective cutting-edge knowledge that can be materialised in rsc.li/greenchem greener and more sustainable products and processes in a challenging world. 1. Historical perspective on the struct. We cannot change behaviour and properties of chemicals ff under given conditions. How they do this is according to their similarities and di erences of green nature. -

Environmental Chemistry

Narrative for a Lecture on Environmental Chemistry Slide 1: Environmental chemistry is that branch of chemical science that deals with the production, transport, reactions, effects, and fates of chemical species in the water, air, terrestrial, and biological environment and the effects of human activities thereon. ENVIRONMENTAL CHEMISTRY Environmental chemistry is that branch of chemical science that deals with the production, transport, reactions, effects, and fates of chemical species in the water, air, terrestrial, and biological environments and the effects of human activities thereon. Reference: Stanley E. Manahan, Fundamentals of Environmental Chemistry, 3rd ed., Taylor & Francis/CRC Press, 2009 ([email protected]) For additional information about environmental chemistry and to download this and other presentations see: http://sites.google.com/site/manahan1937/Home http://manahans1.googlepages.com/ Slide 2: The definition of environmental chemistry is illustrated with a typical pollutant species. In this case sulfur in coal is oxidized to sulfur dioxide gas that is emitted to the atmosphere. The sulfur dioxide gas can be oxidized to sulfuric acid by atmospheric chemical processes, fall back to Earth as acid rain, affect a receptor such as plants, and end up in a "sink" such as a body of water or soil. ILLUSTRATION OF THE DEFINITION OF ENVIRONMENTAL CHEMISTRY 1 SO2 + /2O2 + H2O H2SO4 SO2 H2SO4 S(coal) + O2 SO2 H2SO4, sulfates Slide 3: In the past many environmental problems were caused by practices that now seem to be totally unacceptable as expressed from the quote in this slide from what was regarded as a reputable book on the American chemical industry in 1954. -

The Role of Green Chemistry in Controlling Environmental and Ocean Pollution

International Journal of Oceans and Oceanography ISSN 0973-2667 Volume 11, Number 2 (2017), pp. 217-229 © Research India Publications http://www.ripublication.com The Role of Green Chemistry in Controlling Environmental and Ocean Pollution Rummi Devi Saini Department of Chemistry, SMDRSD College Pathankot-145001, India Abstract Chemistry brought revolution till about the middle of 20th century. In this era, drugs and anti-biotics were discovered. The world’s food supply also increased enormously due to the discovery of hybrid varieties, improved methods of farming, better seeds and use of insecticides, herbicides and fertilizers. Soon the advancement of chemistry started showing its ill-effects [1]. The use of toxic reactants and reagents also make the situation worse. The gaseous, particulate substances, solvents and heat added to the environment due to laboratory and industrial chemical processes, reach directly or indirectly by incorporating in precipitation to oceans if these persist in the environment for long time. As a result these cause harm to both territorial and aquatic life. Long lived gases such as CO2, SO2, nitrogen oxides gets dissolved in ocean water causing its acidification which has been recently recognized as threat to marine organisms especially marine calcifies. At this stage, the beginning of Green Chemistry was marked. Green Chemistry is defined as environmentally benign chemistry. Green chemistry is one of the most explored topics these days. Main research on green chemistry aims to minimize or eliminate the formation of harmful bi-products and to maximize the desired products in an environment friendly way. The three main developments in green chemistry include the use of super critical carbon dioxide, water as green solvent, aqueous hydrogen peroxide as an oxidizing agent and use of hydrogen in asymmetric synthesis. -

Environmental Sciences 1

Environmental Sciences 1 ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES Emerita Associate Professor: Jane Roberts Specific Requirements for Admission to the Program Director: Mary Ann Vinton Environmental Science Major Program Office: Hixson-Lied Science Building, Room 438 and Creighton • Successful completion of EVS 113 Introduction To Atmospheric Hall 110 Sciences or BIO 201 General Biology: Organismal and Population The Environmental Science Program approaches environmental issues or CHM 203 General Chemistry I and CHM 204 General Chemistry I from a strong natural science perspective yet transcends disciplinary Laboratory. boundaries and prepares students to analyze and solve complex problems with scientific, societal and ethical dimensions. The program Majors in Environmental Sciences is interdepartmental, with 19 faculty from eight departments: Biology, • B.S. Evs., Environmental Science: Global and Environmental Systems Chemistry, Communication Studies, Cultural and Social Studies, History, Track (http://catalog.creighton.edu/undergraduate/arts-sciences/ Philosophy, Physics and Political Science. environmental-sciences/environmental-science-global-environmental- systems-bsevs/) The major produces well-rounded scientists with the background and • B.S. Evs., Environmental Science: Organismal/Population Ecology skills necessary to enter graduate degree programs or gain employment Track (http://catalog.creighton.edu/undergraduate/arts-sciences/ in diverse environmental careers such as conservation biology, natural environmental-sciences/environmental-science-organismal- -

Environmental Studies for Undergraduate Courses

Environmental Studies For Undergraduate Courses Erach Bharucha CORE MODULE SYLLABUS FOR ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES FOR UNDER GRADUATE COURSES OF ALL BRANCHES OF HIGHER EDUCATION Vision The importance of environmental science and environmental studies cannot be disputed. The need for sustainable development is a key to the future of mankind. Continuing problems of pollution, loss of forget, solid waste disposal, degradation of environment, issues like economic productivity and national security, Global warming, the depletion of ozone layer and loss of biodiversity have made everyone aware of environmental issues. The United Nations Coference on Environment and Development held in Rio de Janerio in 1992 and world Summit on Sustainable Development at Johannesburg in 2002 have drawn the attention of people around the globe to the deteriorating condition of our environment. It is clear that no citizen of the earth can afford to be ignorant of environment issues. Environmental management has captured the attention of health care managers. Managing environmental hazards has become very important. Human beings have been interested in ecology since the beginning of civilization. Even our ancient scriptures have emphasized about practices and values of environmental conservation. It is now even more critical than ever before for mankind as a whole to have a clear understanding of environmental concerns and to follow sustainable development practices. India is rich in biodiversity which provides various resources for people. It is also basis for biotechnology. Only about 1.7 million living organisms have been diescribed and named globally. Still manay more remain to be identified and described. Attempts are made to I conserve them in ex-situ and in-situ situations. -

ENVS Environmental Science 1

ENVS Environmental Science 1 ENVS 7170 Applied Environmental Chemistry ENVS Environmental 3 Credit Hours. 3 Lecture Hours. 0 Lab Hours. This course covers a variety of chemical fields as they apply to the five essential human needs: water, food, health, waste management, Science and energy. Various materials, including metals, inorganic and organic compounds, polymers, and proteins, as well as their applications, will ENVS 2202 Environmental Science be introduced. Basic research and cutting-edge technologies will be 3 Credit Hours. 3 Lecture Hours. 0 Lab Hours. discussed. This course is an interdisciplinary course integrating principles from Prerequisite(s): Admission to the Environmental Science graduate biology, chemistry, ecology, geology, and non-science disciplines as programs. related to the interactions of humans and their environment. Issues ENVS 7180 Environmental Modeling of local, regional, and global concern will be used to help students 3 Credit Hours. 3 Lecture Hours. 0 Lab Hours. explain scientific concepts and analyze practical solutions to complex An introduction to the study of environmental phenomena that environmental problems. Emphasis is placed on the study of ecosystems, exhibit complexity emergent from a wide variety of parameters. An human population growth, energy, pollution, and other environmental interdisciplinary course that employs the study of a variety of physical, issues and important environmental regulations. biological, and chemical problems. Students learn how to construct and analyze minimal mathematical, physical, and computational models ENVS 7110 Integrative Environmental Science that provide informative answers to precise questions about: population 3 Credit Hours. 3 Lecture Hours. 0 Lab Hours. dynamics; species interactions (e.g., competition, predation, parasitism); This course will explore the complex interdisciplinary nature of reaction kinetics; sedimentation; biological oscillators; coupled reaction environmental science. -

Environmental Assessment of Two Use Cycles of Recycled Aggregate Concrete

sustainability Article Environmental Assessment of Two Use Cycles of Recycled Aggregate Concrete Tereza Pavl ˚u 1,* , Vladimír Koˇcí 2 and Petr Hájek 1 1 University Centre for Energy Efficient Buildings, Technical University, Prague, Trinecka 1024, 273 43 Bustehrad, Czech Republic; [email protected] 2 Department of Environmental Chemistry, Faculty of Environmental Technology, University of Chemistry and Technology, Technicka 5, 166 28 Praha 6—Dejvice, Prague, Czech Republic; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +420-724-507-838 Received: 30 September 2019; Accepted: 1 November 2019; Published: 5 November 2019 Abstract: The main goal of this study was to compare two use cycles of natural aggregate concrete and recycled aggregate concrete, which is another way to compare the environmental impacts of recycled materials. A series of concrete mixtures with various replacement ratios of primary resources with recycled ones were prepared for this study. The mechanical properties of concrete mixtures were examined and were used for the design of structural elements in the same utilized properties. The two use cycles of a structural element were compared using life cycle assessment (LCA). In the first use cycle, the LCA of the structural element containing only primary raw materials was assessed. In the second use cycle, the LCA of a structural element in which primary materials were partially replaced by recycled ones was assessed. The obtained results confirm the potential use of high-quality recycled aggregate originating from local sources in some applications in building structures. Furthermore, the environmental assessment indicates the benefits of using recycled materials, such as environmental savings, especially the reduction of primary resource use, embodied energy, and embodied emissions, as well as reduction of the pressure on landfill sites. -

Green and Sustainable Chemistry Education: Nurturing a New Generation of Chemists

Green and sustainable chemistry education: Nurturing a new generation of chemists Foundation Paper for GCO II Part IV 23 January 2019 Vania Zuin, Departamento de Quimica, Universidade Federal de Sao Carlos, Brazil Ingo Eilks, Universität Bremen, Institute for Science Education Disclaimer The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Moreover, the views expressed do not necessarily represent the decision or the stated policy of the United Nations Environment Programme, nor does citing of trade names or commercial processes constitute endorsement. 1 Contents 1. A new way of teaching chemistry ......................................................................................................... 1 2. Education reform gaining momentum in many countries, but some regions lagging behind ............. 5 3. Overcoming barriers: key determinants for effective educational reform ........................................ 12 4. Options for action ............................................................................................................................... 15 References .................................................................................................................................................. 15 2 1. A new way of teaching