Upravený Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hodnotící Zpráva DDM Prachatice

Dům dětí a mládeže, Prachatice, Ševčíkova 273 Ševčíkova 273/II, Prachatice 383 01 Email: [email protected] Hodnotící zpráva DDM Prachatice školní rok 2019/2020 Na základě podkladů HZ vedoucích pracovišť zpracovaly: Mgr. Veronika Veselovská, Bc. Renata Jandová, Bc. Jiří Machart V Prachaticích 31. 10. 2020 OBSAH 1. ZÁKLADNÍ ÚDAJE O ŠKOLSKÉM ZAŘÍZENÍ ................................................................................................. 3 1.1. ZŘIZOVATEL ............................................................................................................................................... 3 1.2. IDENTIFIKAČNÍ ÚDAJE ................................................................................................................................... 3 1.3. VEDENÍ ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.4. VEDOUCÍ PRACOVIŠŤ ................................................................................................................................... 3 1.5. CHARAKTERISTIKA ŠKOLSKÉHO ZAŘÍZENÍ .......................................................................................................... 5 1.6. PROFIL ÚČASTNÍKŮ ZÁJMOVÉHO VZDĚLÁVÁNÍ ................................................................................................... 6 2. ČINNOSTI ZÁJMOVÉHO VZDĚLÁVÁNÍ VE ŠKOLSKÉM ZAŘÍZENÍ ................................................................. 7 2.1. PRAVIDELNÁ ČINNOST ................................................................................................................................. -

JEWISH HERITAGE SITES in South Bohemia

JEWISH HERITAGE SITES in South Bohemia www.jiznicechy.cz JEWISH HERITAGE SITES in South Bohemia There used to be several hundred Jewish communi- ties in Bohemia, each of which had a synagogue or at least a prayer house or room, and a Jewish cemetery. Several dozen such communities existed in South Bohemia as well, but today not a single one remains. Most of their members died during World War II in concentration and extermination camps, whereas many of those who survived emigrated after 1948 or 1968. The South Bohemian Region also falls under the jurisdiction of the Jewish community in Prague, which also manages all Jewish cemeteries and several other preserved South Bohemian Jewish heritage sites. Another problem was that in the second half of the 19th century, many Jews migrated from the villages to the cities. Many rural Jewish communities became extinct and many synagogues were abandoned, some were sold to private individuals and modified for other purposes, and others were purchased by Christian church organizations. Since the Velvet Revolution, some of these have been reconstructed and now serve as museums; in South Bohemia, for example, these are the synagogues in Bechyně, Český Krumlov, and Čkyně. Of the fifty South Bohemian Jewish cemeteries, the rarely preserved Jewish cemetery in Jindřichův Hradec deserves particular attention; it is one of the oldest preserved Jewish cemeteries in the Czech Republic. JEWISH HERITAGE SITES in South Bohemia JEWISH HERITAGE SITES in South Bohemia 1 Babčice 2 Bechyně According to written sources, Jews lived in Babčice from the middle Written sources show that Jews were in Bechyně from the second half of the 18th century at the latest. -

Investiční a Další Priority

Investiční a další priority - seznam projektových záměrů pro investiční intervence v SC 2.4 IROP a pro integrované nástroje ITI, IPRÚ a CLLD a seznam dalších záměrů pro území, zpracovaný pro SO ORP Prachatice Příloha Strategického rámce MAP SO ORP Prachatice Verze 2.0 leden 2017 Schváleno Řídícím výborem MAP 20.1.2017 MAS Šumavsko, z.s. Projekt: Místní akční plán rozvoje vzdělávání pro ORP Prachatice Registrační číslo projektu: CZ.02.3.68/0.0/0.0/15_005/0000329 Sídlo: Archiváře Teplého 102, 387 06 Malenice www.massumavsko.cz +420 724 004 484 Obsah SEZNAM PROJEKTOVÝCH ZÁMĚRŮ ZÁKLADNÍCH ŠKOL A MATEŘSKÝCH ŠKOL ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Základní škola Mistra Jana Husa a Mateřská škola Husinec ........................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Základní škola a Mateřská škola Ktiš ........................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Základní škola a Mateřská škola Nová Pec .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 9 Základní škola a Mateřská škola Strunkovice nad Blanicí ......................................................................................................................................................................... -

List of Municipalities of the Czech Republic Including the Division Based on the Population Criterion

Appendix 4 to the Invitation to Tender for the award of rights to use radio frequencies to provide an electronic communications network in the 3600–3800 MHz band List of municipalities of the Czech Republic including the division based on the population criterion List of municipalities of the Czech Republic including the division based on the population criterion 1 LIST OF MUNICIPALITIES OF THE CZECH REPUBLIC IN THE CATEGORY OF 2,001 TO 5,000 INHABITANTS Number of District Id. Municipality Id. Municipality name inhabitants District of Benešov CZ0201 529451 Bystřice 4,336 CZ0201 529516 Čerčany 2,763 CZ0201 530310 Neveklov 2,547 CZ0201 534382 Sázava 3,786 CZ0201 530905 Votice 4,596 District of Beroun CZ0202 531324 Komárov 2,420 CZ0202 532011 Zdice 4,126 CZ0202 532029 Žebrák 2,141 District of Kladno CZ0203 532169 Buštěhrad 3,157 CZ0203 532371 Hřebeč 2,015 CZ0203 541991 Lány 2,060 CZ0203 532576 Libušín 2,954 CZ0203 532983 Tuchlovice 2,465 CZ0203 533017 Unhošť 4,428 CZ0203 533041 Velvary 3,080 CZ0203 533050 Vinařice 2,035 CZ0203 533114 Zlonice 2,289 District of Kolín CZ0204 537641 Pečky 4,549 CZ0204 533807 Týnec nad Labem 2,074 CZ0204 533831 Velim 2,184 CZ0204 533840 Velký Osek 2,257 District of Kutná Hora CZ0205 534498 Uhlířské Janovice 3,055 CZ0205 534587 Vrdy 2,888 CZ0205 534633 Zruč nad Sázavou 4,732 District of Mělník CZ0206 534935 Kostelec nad Labem 3,883 CZ0206 571784 Libiš 2,127 CZ0206 535222 Tišice 2,184 CZ0206 535273 Veltrusy 2,018 CZ0206 535320 Všetaty 2,268 District of Mladá Boleslav CZ0207 535443 Bělá pod Bezdězem 4,840 CZ0207 535672 Dobrovice 3,351 CZ0207 535702 Dolní Bousov 2,641 CZ0207 570826 Kosmonosy 4,964 CZ0207 536270 Luštěnice 2,129 District of Nymburk CZ0208 537489 Městec Králové 2,921 CZ0208 537764 Sadská 3,302 District of Praha-východ CZ0209 538230 Hovorčovice 2,255 CZ0209 538272 Jirny 2,652 Opening of the Tender – Appendix No. -

Mikroregion Vlachovo Březí

MAS Šumavsko, z. s. Rozvojová strategie MAS STRATEGIE KOMUNITNĚ VEDENÉHO MÍSTNÍHO ROZVOJE 2014 – 2020 místní akční skupiny MAS Šumavsko, z. s. „ŽIVÉ A ŠŤASTNÉ ŠUMAVSKO“ Schváleno Valnou hromadou MAS Šumavsko, z.s. Dne 19. ledna 2016 Strana 2 Obsah 1. POPIS ZÁJMOVÉHO ÚZEMÍ ..................................................................................................................... 6 2. GEOGRAFICKÁ POLOHA ........................................................................................................................ 27 Území a klima okresu Prachatice (S1, S2, O12) ........................................................................................... 27 Území a klima okresu Strakonice ................................................................................................................ 27 3. LIDSKÉ ZDROJE ÚZEMÍ .......................................................................................................................... 28 Obyvatelstvo na území MAS Šumavsko, z. s. .............................................................................................. 28 4. SOCIÁLNÍ ZDROJE ÚZEMÍ ...................................................................................................................... 34 Kulturní a sportovní zařízení na území MAS Šumavsko (S7, S13, S14) ........................................................ 34 Společenský život na území MAS Šumavsko (S14, W7, W23, O6, O7, T4, T5, T12, T20, T21, T22) ............. 35 5. OBLAST SOCIÁLNÍCH SLUŽEB ............................................................................................................... -

Length of Path 9,1 Km 1 the Most Famous Historical Route

WANDERINGS THROUGH ŠUMAVA AND THE BAVARIAN FOREST Following the Golden Trail 1 The most famous historical route Length of Path 9,1 km The most famous historical route The most famous historical route is the Golden Trail. Its oldest route is its Prachatice branch, sometimes called the Lower branch. It has existed since the early 10th century, even though its name “Golden” comes from the 16th. It led from Passau through Sal- zweg, Waldkirchen, Grainet, Bischofsreut, it crossed the border by Marchhäuser and continued across České Žleby, Volary, Cud- rovice, around the Hus castle, through Albre- chtovice and to Prachatice. The Vimperk (Middle) branch of the Golden Trail is younger. It is only first mentioned in 1312. The trail separated from the Prachatice branch by Ernsting and led through Hinter- schmiding and Herzogsreut, below Kunžvart to Horní Vlatavice and through Solná Lhota to Vimperk. The Kašperské Hory (Upper) branch was built around 1356. It led across today’s Röhrnbach, Freyung, Mauth, Finsterau, Buči- na, Kvilda, Horská Kvilda, Červená (after the Hussite Wars through Kozí Hřbety – there was a custom house too) to Kašperské Hory and then to Sušice. At the same time, king Charles IV rules to build the Golden Road. A document has sur- vived from that year which has Charles IV granting Heinczlin Bader hereditary use of land between Malá Losenice and Červená in return for his help during the construction of a road from Passau to Bohemia. Ten years later, Charles IV ordered all merchants travel- ling on the road to stay overnight in Kašper- ské Hory. -

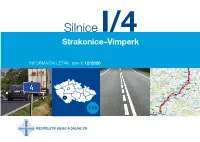

Silnice I/4 Strakonice–Vimperk

Silnice I/4 Strakonice–Vimperk Zvotoky Benešov Silnice I/4 Stod Příbram Přední 4 Libětice Zborovice Přeštice Sedlčany stavba Blovice Strakonice Votice INFORMAČNÍ LETÁK, stav k 12/2020 Strakonice – Vimperk Zahorčice stavba 5 Nepomuk Plzeňský kraj Klatovy Blatná Jihočeský kraj Strunkovice Milevsko Úlehle nad Volyňkou Nová Ves Horažďovice Tábor Sušice Němčice Písek Hoslovice Němětice Strakonice Hoštice Soběslav Nihošovice Týn stavba 7 nad Vltavou Vodňany Vimperk Prachatice Drážov Přechovice Milejovice České Třeboň 170 stavba 8 Budějovice Dřešín Čestice Dobrš Volyně Střítež Vrbice Nuzín stavba 2 142 171 Vacov Zechovice Krušlov stavba 4 Nišovice Litochovice Vacovice stavba 3 170 Nahořany výsledná varianta 144 trasa dle ÚP Volyně Nespice stavba 9 Malenice stavba 6 Předslavice 171 4 Onšovice Dolany Lčovice Tvrzice Putkov stavba 1 Čkyně Zálezly Bušanovice Račov Hradčany stavba 10 Bohumilice Výškovice Újezdec Bošice 0 2,5 5 km Smrčná Geografická data poskytl VGHMÚř Dobruška, © MO ČR, 2008 stavba 11 Radhostice Vlachovo Březí C68 145 Svatá Maří Vimperk 4 Strážný 145 Chlumany Strakonice–Vimperk Silnice I/4 DOPRAVNÍ VÝZNAM STAVBY UMÍSTĚNÍ A POPIS STAVBY Účelem studie je vyhledat trasu silnice I/4 Nová trasa silnice I/4 je navržena tak, aby začína- zí trasa z okresu Strakonice do okresu Prachatice. tak, aby v úseku Strakonice–Volyně vyho- la těsně za mostem v Předních Zborovicích v km Zde navržená trasa výškově i směrově navazuje na vovala kategorii silnice S 11,5/70 a v úseku 114,593 podle pasportu silnice I/4. Trasa nové silnice dnešní silnici, kterou opouští až v km 13,250. V km Volyně–Vimperk kategorii silnice S 11,5/60. -

South Bohemia Region

Mortgage Boom in the Czech Republic The Czech Economy Is Experiencing an Exceptional Period Design, Image, Quality South Bohemia Region 11-12 2006 CONTENTS Ministry of Industry and Trade I INTRODUCTION CZECH BUSINESS Question of the Month for Martin Tlapa, Deputy Minister of Industry AND TRADE and Trade.........................................................................................................4 Economic Bi-monthly Magazine with I ECONOMIC POLICY a Supplement is Designed for Foreign The Czech Economy Is Experiencing an Exceptional Period...............................5 Partners, Interested in Cooperation with Mortgage Boom in the Czech Republic............................................................7 the Czech Republic I Issued by: INVESTMENT Czech Republic – On its Way to Becoming and Ideal Location PP AGENCY s.r.o. for Sophisticated Investment ............................................................................8 Myslíkova 25, 110 00 Praha 1, Czech Republic PP Agency I BUSINESS AND PRODUCTION Company with the ISO 9001 certified quality management system for publishing services Zetor Successful with Smaller Tractors on Russian Market ..............................10 Candy Ovens Lit by Czech Light Bulbs............................................................10 EDITORIAL BOARD: Martin Tlapa (Chairman), Ivan Angelis, I HOW TO DO BUSINESS IN THE CZECH REPUBLIC Zdena Balcerová, Jiří Eibel, Zbyněk Frolík, Companies from EU Able to Found Cooperatives in the Czech Republic ........12 Růžena Hejná, Alžběta Honsová, Josef -

ČD Šumava 7 7 7 18:27 18:02 Jede V Pátek a V Sobotu Od 21

Nové Údolí - Waldkirchen (-Freyung, NP Bavorský les) a zpět Autobusy RBO 6 6 7 7 6 6 7 6 7 7 6 6 7 6 6 7 6 7 7 6 7 6 9:02 10:52 11:12 12:32 16:48 18:00 19:02 Nové Údolí 9:00 10:10 11:10 12:30 16:36 17:59 19:00 19:02 7:53 9:06 10:56 11:16 12:36 16:52 18:04 19:06 Haidmühle, Scherz 8:57 10:07 11:07 12:27 16:33 17:58 18:57 18:59 20:18 7:59 9:12 11:02 11:22 12:42 16:58 18:10 19:12 Alreichenau, Kirche 8:49 9:59 10:59 12:19 16:25 17:47 18:49 18:51 20:10 8:02 9:15 11:05 11:25 12:45 17:01 18:13 19:15 Neureichenau, Rathaus 8:46 9:56 10:56 12:16 16:22 17:44 18:46 18:48 20:07 9:32 11:22 11:42 13:02 17:18 18:29 19:32 Waldkirchen, Bf. 8:28 9:38 10:38 11:58 16:00 17:29 18:28 18:30 19:49 8:20 9:38 11:28 11:48 13:08 17:24 *18:36 19:38 Waldkirchen, Bus Bf. 8:22 10:32 11:52 16:04 17:23 18:22 *18:22 19:43 Vlaky Ilztalbahn 7 7 6 7 6 7 6 7 6 7 6 7 6 7 7 6 7 9:36 11:56 11:56 **18:30 19:36 Waldkirchen 9:40 11:57 15:58 17:30 **18:27 19:40 10:01 12:21 12:21 **18:56 20:01 Freyung 9:15 11:30 15:35 17:05 **18:02 19:15 Autobusy RBO 7 7 6 7 6 7 6 7 6 7 6 7 7 6 10:05 12:30 18:56 Freyung, Bf. -

Šumava – Bayerischer Wald/Unterer Inn – Mühlviertel

Crossing the borders. Studies on cross-border cooperation within the Danube Region The Euroregion Šumava – Bayerischer Wald/Unterer Inn – Mühlviertel Contents 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 2 2. Development of cross-border cooperation .......................................................................... 5 2.1 The development of the Euroregion Šumava-Bayerischer Wald/Unterer Inn- Mühlviertel ..................................................................................................................... 6 3. Geographical characteristics of the area .............................................................................. 8 4. Organisational and institutional structures, activities ......................................................... 16 4.1 The emergence of the institution as a single cross-border unit ................................ 16 4.2 Spatial definition and membership in the Euroregion ............................................... 17 4.3 Organisational structure .............................................................................................. 19 4.4 Main activities .............................................................................................................. 21 5. Composition of the working group ..................................................................................... 23 6. Main activity fields ............................................................................................................ -

Time Coordination of Periodic Passenger Train Connections in Conditions of Single-Track Lines

Hindawi Mathematical Problems in Engineering Volume 2021, Article ID 3876561, 17 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/3876561 Research Article Time Coordination of Periodic Passenger Train Connections in Conditions of Single-Track Lines Filip Lorenz,1 Vit Janos,2 Dusan Teichmann,2,3 and Michal Dorda 3 1Department of Control Systems and Instrumentation, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, VSB–Technical University of Ostrava, 17. listopadu 2172/15, 708 00 Ostrava-Poruba, Czech Republic 2Department of Logistics and Management of Transport, Faculty of Transportation Sciences, CTU in Prague, Konviktska 20, 110 00 Prague, Czech Republic 3Institute of Transport, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, VSB–Technical University of Ostrava, 17. listopadu 2172/15, 708 00 Ostrava-Poruba, Czech Republic Correspondence should be addressed to Michal Dorda; [email protected] Received 30 June 2020; Revised 12 January 2021; Accepted 6 February 2021; Published 9 March 2021 Academic Editor: Luca D'Acierno Copyright © 2021 Filip Lorenz et al. )is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. )e article addresses creation of a mathematical model for a real problem regarding time coordination of periodic train connections operated on single-track lines. )e individual train connections are dispatched with a predefined tact, and their arrivals at and departures to predefined railway stations (transfer nodes) need to be coordinated one another. In addition, because the train connections are operated on single-track lines, trains that pass each other in a predefined railway stations must be also coordinated. -

Submission of the Government on the Merits

EUROPEAN COMMITTEE OF SOCIAL RIGHTS COMITÉ EUROPÉEN DES DROITS SOCIAUX 19 November 2014 Case Document No. 3 European Roma and Travellers Forum (ERTF) v. Czech Republic Complaint No. 104/2014 SUBMISSION OF THE GOVERNMENT ON THE MERITS Registered at the Secretariat on 12 November 2014 The Submission of the Government of the Czech Republic on the Collective Complaint No. 104/2014 filed against the Czech Republic by the European Roma and Travellers Forum I Subject of the Complaint In the Collective Complaint submitted on 20 February 2014, registered under the reference number 104/2014, the European Roma Travellers Forum ('ERTF') states that the Czech Republic violated Articles 11 and 16 of the European Social Charter of 1961 ('1961 Charter') in conjunction with the non-discrimination principle enshrined in the Preamble of the 1961 Charter, particularly in the field of the housing situation of Roma as well as their right to health. The Complaint has been submitted with the purpose of ensuring the full realisation of social rights. II Position of the Government of the Czech Republic on the statements of the ERTF concerning Article 16 Article 16, which guarantees social, legal and economic protection of families, prescribes as follows: With a view to ensuring the necessary conditions for a full development of the family, which is a fundamental unit of society, the Contracting Parties undertake to promote economic, legal and social protection of family life by such means as social and family benefits, fiscal arrangements, provision of family housing, benefits for the newly married, and other appropriate means. In the Complaint, the ERTF describes the situation in the Czech Republic as follows: „b) Discrimination against Roma in the Czech Republic in the field of housing Large number of Roma in the Czech Republic today live segregated from non-Roma, in violation of international human rights norms banning racial segregation.