Medieval Saintonge Pottery in Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spotlight Central and Tayside Residential Market Summer 2016

Savills World Research UK Residential Spotlight Central and Tayside Residential Market Summer 2016 Drumfada (Offers Over £540,000) in Dundee, where overall transactional activity increased annually by 13%. SUMMARY Growing confidence in lower price brackets fuels prime activity across Central and Tayside ■ The market below £400,000 across FIGURE 1 Central and Tayside has outperformed Residential values annual change forecast Scotland and continues to attract second home owners and downsizers Area 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 from outside the region. Prime GB regional 2.5% 3.5% 6.0% 4.5% 4.0% ■ Strong growth across lower price bands is now leading to improved Prime Scotland 2.0% 3.5% 4.0% 4.0% 4.0% prime activity in the city and town locations of Angus, Dundee, Fife, Prime Central & Tayside 1.0% 2.5% 3.5% 3.5% 3.5% Stirling, and Perth. Mainstream UK 5.0% 3.0% 3.0% 2.5% 2.5% ■ The prime market has adjusted to Mainstream Scotland 3.0% 3.0% 2.5% 2.5% 2.5% taxation changes in the city hotspots of Edinburgh and Glasgow, with Mainstream Central & Tayside 2.5% 2.5% 2.0% 2.0% 2.0% growth spreading into traditional suburbs and commuter areas. Source: Savills Research savills.co.uk/research 01 Spotlight | Central and Tayside Residential Market CENTRAL AND to the city hubs of Edinburgh and Stirling city and the hotspots of Glasgow. As a consequence, there Dollar, Dunblane and Killearn. Tayside MARKET will be opportunities for buyers to take advantage of relative The Fife market was in line with affordability (Figure 1). -

Tayside, Angus and Perthshire Fibromyalgia Support Group Scotland

Tayside, Angus and Perthshire Angus Long Term Conditions Support Fibromyalgia Support Group Scotland Groups Offer help and support to people suffering from fibromyalgia. This help and support also extends to Have 4 groups of friendly people who meet monthly at family and friends of sufferers and people who various locations within Angus and offer support to people would like more information on fibromyalgia. who suffer from any form of Long Term Condition or for ANGUS Directory They meet every first Saturday of every month at carers of someone with a Long Term Condition as well as Ninewells Hospital, Dundee. These meetings are each other, light refreshments are provided. to Local held on Level 7, Promenade Area starting at 11am For more information visit www.altcsg.org.uk or e-mail: Self Help Groups and finish at 1pm. [email protected] For more information contact TAP FM Support Group, PO Box 10183, Dundee DD4 8WT, visit www.tapfm.co.uk or e-mail - [email protected] . Multiple Sclerosis Society Angus Branch For information about, or assistance about the Angus Gatepost Branch please call 0845 900 57 60 between 9am - 8pm or e-mail Brian Robson at mailto:[email protected] GATEPOST is run by Scottish farming charity RSABI and offers a helpline service to anyone who works on the land in Scotland, and also their families. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic They offer a friendly, listening ear and a sounding post for Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) you at difficult times, whatever the reason. If you’re The aims of the support group are to give support to worried, stressed, or feeling isolated, they can help. -

Tayside November 2014

Regional Skills Assessment Tayside November 2014 Angus Perth and Kinross Dundee City Acknowledgement The Regional Skills Assessment Steering Group (Skills Development Scotland, Scottish Enterprise, the Scottish Funding Council and the Scottish Local Authorities Economic Development Group) would like to thank SQW for their highly professional support in the analysis and collation of the data that forms the basis of this Regional Skills Assessment. Regional Skills Assessment Tayside Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Context 5 3 Economic Performance 7 4 Profile of the Workforce 20 5 People and Skills Supply 29 6 Education and Training Provision 43 7 Skills Mismatches 63 8 Economic and Skills Outlook 73 9 Questions Arising 80 sds.co.uk 1 Regional Skills Assessment Section 1 Tayside Introduction 1 Introduction 1.1 The purpose of Regional Skills Assessments This document is one of a series of Regional Skills Assessments (RSAs), which have been produced to provide a high quality and consistent source of evidence about economic and skills performance and delivery at a regional level. The RSAs are intended as a resource that can be used to identify regional strengths and any issues or mismatches arising, and so inform thinking about future planning and investment at a regional level. 1.2 The development and coverage of RSAs The content and geographical coverage of the RSAs was decided by a steering group comprising Skills Development Scotland, Scottish Enterprise, the Scottish Funding Council and extended to include the Scottish Local Authorities Economic Development Group during the development process. It was influenced by a series of discussions with local authorities and colleges, primarily about the most appropriate geographic breakdown. -

THE HISTORIC ARCHITECTURE of MORAY Ronald G

THE HISTORIC ARCHITECTURE OF MORAY Ronald G. Cant In this paper the term 'historic architecture' has been taken, arbitrarily perhaps but conveniently, to cover the period from the early twelfth cen tury onwards when Moray came to be effectively absorbed into the medi eval Scottish kingdom, itself being integrated into a pattern of life developed in most parts of Europe in what has sometimes been called 'the medieval renaissance'. In terms of organisation this pattern involved four major elements. First was the authority of the King of Scots based on royal castles like those of Elgin and Forres under such officers as constables or sheriffs. Second, associated with certain castles, were settlements of merchants and crafts men that might (as at Elgin and Forres) develop into organised urban communities or burghs. Third, in the surrounding countryside, were the defensible dwellings of greater and lesser lords holding lands and authority directly or indirectly from the king and ultimately answerable to him. Fourth was the medieval church, an international organisation under the Pope but enjoying a certain autonomy in each of the countries in which it functioned and closely associated with these other elements at every level. Kings, Barons, and Burghers Each element in this 'medieval order' had its distinctive building require ments. For the king control of the previously strongly independent regional dominion of Moray stretching from west of the River Ness to east of the Spey was secured by the building of castles (with associated sheriffs) at Inverness, Nairn, Forres, and Elgin. Beyond the Spey was another at Banff but in civil affairs most of the area there had little direct association with Moray until comparatively recently, while in the west Inverness became the seat of a different and more extensive authority. -

TAYSIDE VALUATION APPEAL PANEL LIST of APPEALS for CONSIDERATION by the VALUATION APPEAL COMMITTEE at Robertson House, Whitefriars Crescent, PERTH on 24 June 2021

TAYSIDE VALUATION APPEAL PANEL LIST OF APPEALS FOR CONSIDERATION BY THE VALUATION APPEAL COMMITTEE At Robertson House, Whitefriars Crescent, PERTH on 24 June 2021 Assessor's Appellant's Case No Details & Contact Description & Situation Appellant NAV RV NAV RV Remarks 001 08SKB2786000 SORTING OFFICE ROYAL MAIL GROUP LIMITED £11,900 £11,900 757371 0002 87-93 HIGH STREET 100 VICTORIA EMBANKMENT Update 2019 KINROSS LONDON 31 March 2020 KY13 8AA EC4Y 0HQ 002 12PTR0127000 WAREHOUSE DMS PARTNERS LTD £35,100 £35,100 £17,550 £17,550 719396 0005 UNIT 1A PER ANDREW REILLY ASSOC. LTD Update 2020 ARRAN ROAD 31 RUTLAND SQUARE 12 June 2020 PERTH EDINBURGH PH1 3DZ EH1 2BW 003 12PTR0127125 WAREHOUSE DMS PARTNERS LTD £17,200 £17,200 £8,600 £8,600 524162 0002 UNIT 1B PER ANDREW REILLY ASSOC. LTD Update 2020 ARRAN ROAD 31 RUTLAND SQUARE 12 June 2020 PERTH EDINBURGH PH1 3DZ EH1 2BW 004 12PTR0095000 WAREHOUSE & OFFICE REMBRAND TIMBER LTD £36,900 £36,900 £18,450 £18,450 772904 0003 ARRAN ROAD PER ANDREW REILLY ASSOC. LTD Update 2020 PERTH 31 RUTLAND SQUARE 19 June 2020 PH1 3DZ EDINBURGH EH1 2BW 005 12PTR0127250 WAREHOUSE BELLA & DUKE LTD £30,100 £30,100 522012 0002 UNIT 2 PER ANDREW REILLY ASSOCIATES LTD Update 2020 ARRAN ROAD 31 RUTLAND SQUARE 23 June 2020 PERTH EDINBURGH PH1 3DZ EH1 2BW 006 09SUC0144000 YARD SUEZ RECYCLING & RECOVERY UK LTD £49,800 £49,800 766760 0002 WOOD CHIP PROCESSING PLANT PER AVISON YOUNG Update 2019 BINN HILL 1ST FLOOR, SUTHERLAND HOUSE 29 March 2020 GLENFARG 149 ST VINCENT STREET PERTH GLASGOW PH2 9PX G2 5NW Page 1 Assessor's Appellant's -

Stewart2019.Pdf

Political Change and Scottish Nationalism in Dundee 1973-2012 Thomas A W Stewart PhD Thesis University of Edinburgh 2019 Abstract Prior to the 2014 independence referendum, the Scottish National Party’s strongest bastions of support were in rural areas. The sole exception was Dundee, where it has consistently enjoyed levels of support well ahead of the national average, first replacing the Conservatives as the city’s second party in the 1970s before overcoming Labour to become its leading force in the 2000s. Through this period it achieved Westminster representation between 1974 and 1987, and again since 2005, and had won both of its Scottish Parliamentary seats by 2007. This performance has been completely unmatched in any of the country’s other cities. Using a mixture of archival research, oral history interviews, the local press and memoires, this thesis seeks to explain the party’s record of success in Dundee. It will assess the extent to which the character of the city itself, its economy, demography, geography, history, and local media landscape, made Dundee especially prone to Nationalist politics. It will then address the more fundamental importance of the interaction of local political forces that were independent of the city’s nature through an examination of the ability of party machines, key individuals and political strategies to shape the city’s electoral landscape. The local SNP and its main rival throughout the period, the Labour Party, will be analysed in particular detail. The thesis will also take time to delve into the histories of the Conservatives, Liberals and Radical Left within the city and their influence on the fortunes of the SNP. -

Autumn Trip to Inverness 2017

Autumn trip to Inverness 2017 Brian weaving his magic spell at Clava Cairns © Derek Leak Brian Ayers spends part of his year in the north low buttress with a recumbent stone in the SE. of Scotland and offered to show us the area The three Clava cairns cross a field near round Inverness. Amazing geology and scenery, Culloden Moor. These are late Neolithic/Bronze intriguing stone circles, carved Pictish crosses, Age and two circles have outliers like spokes with snatches of Scottish history involving on a wheel ending in a tall upright. One circle ambitious Scottish lords, interfering kings is heaped with stones and revetted, with the of England, Robert the Bruce, and rebellious very centre stone-free. Another is completely Jacobites added to the mix. Scotland’s history covered in stones while the most northerly was long a rivalry between the Highlands and circle has walls surviving to shoulder height Isles, and the Lowlands; the ancient Picts, and and the tunnel entrance probably once roofed. the Scots (from Ireland), and the French. Cup-marked stones mark the entrance to the In the shadow of Bennachie, a large darkest space. mountain, is Easter Aquhorthies stone circle. Standing on the south bank of a now-drained A well preserved recumbent stone circle, sea loch with RAF Lossiemouth to the north, is designated by the huge stone lying on its side the impressive Spynie Palace. For much of its flanked by two upright stones which always early years the bishopric was peripatetic before face SSW, it apparently formed a closed door the Pope allowed the move to Spynie in 1206. -

Assessment of Landscape Sensitivity to Wind Turbine Development in Highland

Assessment of Landscape Sensitivity to Wind Turbine Development in Highland D.R. Miller, S. Bell, M. McKeen, P.L. Horne, J.G. Morrice and D. Donnelly Summary Report Macaulay Land Use Research Institute September 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................................II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.......................................................................................................................II 1 INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................................1 1.1 OBJECTIVES..........................................................................................................................1 1.2 DEFINITION OF KEY TERMS.................................................................................................2 1.3 LIMITATIONS..........................................................................................................................3 2 METHODOLOGY............................................................................................................................4 2.1 BACKGROUND.......................................................................................................................4 2.2 LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT..........................................................................5 2.3 LANDSCAPE CHARACTER SENSITIVITY ............................................................................6 -

Girls Cup Competition 2020

Girls Cup Competition 2020 Girls U16 Cup Competition Pool 1 Pool 2 Pool 3 East Cartha Queens Park Murrayfield Kilbride/Waysiders RFC Wanderers RFC Drumpellier Highland RFC Caithness RFC Lismore RFC Biggar & Friends Tayside & Fife Girls Dumfries Saints RFC Rugby Oban Lorne RFC Grampian Girls Currie Chieftains Wigtownshire RFC Shetland RFC Wolves Rugby Stirling County RFC Leith Rugby Ayr RFC Cup Fixtures (10 aside plus 4 replacements) 02 February 2020 (20 minutes fixtures) Venue: St Andrews & Madras (4 pitches) Pitch 1 o East Kilbride/Waysiders Drumpellier v Grampian Girls (KO 11:00am) o Highland RFC v Wigtownshire RFC (KO 11:30am) o Tayside & Fife Girls Rugby v Ayr RFC (KO 12noon) o Cartha Queens Park RFC v Highland RFC (KO 12:30pm) o Tayside & Fife Girls Rugby v Currie Chieftains (KO 1:00pm) o Shetland RFC v Grampian Girls (KO 1:30pm) o Murrayfield Wanderers RFC v Tayside & Fife Girls Rugby (KO 2:00pm) o Leith Rugby v Grampian Girls (KO 2:30pm) o Biggar & Friends v Highland RFC (KO 3:00pm) Pitch 2 o Lismore RFC v Shetland RFC (KO 11:00am) o Biggar & Friends v Stirling County RFC (KO 11:30am) o East Kilbride/Waysiders Drumpellier v Lismore RFC (KO 12noon) o Biggar & Friends v Oban Lorne RFC (KO 12:30pm) o Ayr RFC v Wolves Rugby (KO 1:00pm) o Cartha Queens Park RFC v Biggar & Friends (KO 1:30pm) o Ayr RFC v Caithness RFC (KO 2:00pm) o Dumfries Saints RFC v Lismore RFC (KO 2:30pm) o Wolves Rugby v Murrayfield Wanderers RFC (KO 3:00pm) Pitch 3 o Dumfries Saints RFC v Leith Rugby (KO 11:00am) o Murrayfield Wanderers RFC v Currie Chieftains -

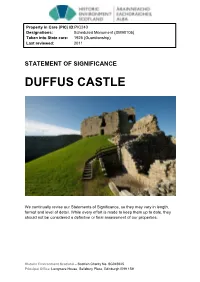

Duffus Castle Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID:PIC240 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90105) Taken into State care: 1925 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2011 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE DUFFUS CASTLE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2018 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH DUFFUS CASTLE SYNOPSIS Duffus Castle is the best-preserved motte-and-bailey castle in state care. It was built c.1150 by Freskin, a Fleming who founded the powerful Moray (Murray) dynasty. -

P898: the Barrett Family Collection

P898: The Barrett Family Collection RECORDS’ IDENTITY STATEMENT Reference number: P898 Alternative reference number: Title: The Barret Family Collection Dates of creation: 1898 - 2015 Level of description: Fonds Extent: 7 linear meters Format: Paper, Wood, Glass, fabrics, alloys RECORDS’ CONTEXT Name of creators: Administrative history: Custodial history: Deposited by Margret Shearer RECORDS’ CONTENT Description: Appraisal: Accruals: RECORDS’ CONDITION OF ACC. ESS AND USE Access: Open Closed until: - Access conditions: Available within the Archive searchroom Copying: Copying permitted within standard Copyright Act parameters Finding aids: Available in Archive searchroom ALLIED MATERIALS Related material: Publication: Notes: Nucleus: The Nuclear and Caithness Archive 1 Date of catalogue: 02 Feb 2018 Ref. Description Dates P898/1 Diaries 1975-2004 P898/1/1 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1975 P898/1/2 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1984 P898/1/3 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1987 P898/1/4 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1988 P898/1/5 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1989 P898/1/6 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1990 P898/1/7 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1991 P898/1/8 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1992 P898/1/9 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1993 P898/1/10 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1995 P898/1/11 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1996 P898/1/12 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1997 P898/1/13 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1998 P898/1/14 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1999 P898/1/15 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 2000 P898/1/16 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 2001 P898/1/17 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 2002 P898/1/18/1 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 2003 P898/1/18/2 Envelope containing a newspaper clipping, receipts, 2003 addresses and a ticket to the Retired Police Officers Association, Scotland Highlands and Island Branch 100 Club (Inside P898/1/18/1). -

Clan Dunbar 2014 Tour of Scotland in August 14-26, 2014: Journal of Lyle Dunbar

Clan Dunbar 2014 Tour of Scotland in August 14-26, 2014: Journal of Lyle Dunbar Introduction The Clan Dunbar 2014 Tour of Scotland from August 14-26, 2014, was organized for Clan Dunbar members with the primary objective to visit sites associated with the Dunbar family history in Scotland. This Clan Dunbar 2014 Tour of Scotland focused on Dunbar family history at sites in southeast Scotland around Dunbar town and Dunbar Castle, and in the northern highlands and Moray. Lyle Dunbar, a Clan Dunbar member from San Diego, CA, participated in both the 2014 tour, as well as a previous Clan Dunbar 2009 Tour of Scotland, which focused on the Dunbar family history in the southern border regions of Scotland, the northern border regions of England, the Isle of Mann, and the areas in southeast Scotland around the town of Dunbar and Dunbar Castle. The research from the 2009 trip was included in Lyle Dunbar’s book entitled House of Dunbar- The Rise and Fall of a Scottish Noble Family, Part I-The Earls of Dunbar, recently published in May, 2014. Part I documented the early Dunbar family history associated with the Earls of Dunbar from the founding of the earldom in 1072, through the forfeiture of the earldom forced by King James I of Scotland in 1435. Lyle Dunbar is in the process of completing a second installment of the book entitled House of Dunbar- The Rise and Fall of a Scottish Noble Family, Part II- After the Fall, which will document the history of the Dunbar family in Scotland after the fall of the earldom of Dunbar in 1435, through the mid-1700s, when many Scots, including his ancestors, left Scotland for America.