Jbaa 123, 3 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Registrerings-Tidende

REGISTRERINGS-TIDENDE FOR VARE- OG FÆLLESMÆRKER FOR A AR ET 1928 UDGIVEN AF DIREKTORATET FOR PATENT- OG VAREMÆRKEVÆSENET M. V. KØBENHAVN TRYKT I BIANCO LUNOS BOGTRYKKERI 1929 Fortegnelse over Anmeldere. Varemærker. Reg. Nr. Aagesen, Niels Harald Ludvig, Skotøjshandel, København 249 Aalborg Margarinefabrik, B.Thorsen, A.-S., Fabrikation af Margarine, Aalborg. .162—63, 966 — Mælkekompagni, A.-S., Mejerivirksomhed, Aalborg 561 Aarhus Oljefabrik, A.-S., Handel med Oljer m. m., Aarhus 291 92 — \ ærktøjsmagasin, se Hansen, Johannes, Indehaver af Abdulla and Company, Limited, Tobaksfabrikation, London 1151 Abrahamson, Emil V., Firmaet, Handel med Kemikalier, København 40 Acetol Products, Inc., Fabrikation af Vægbeklædninger, New York 702 Adressograph Company, Fabrikation, Chikago 644, 850 Aktiengesellschaft vormals B. Siegfried, Fabrikation og Handel, Zofingen i Schweiz.. 1136 Alabastine Company, The, British Limited, Farvefabrikation, South Lambeth ved London 259 »Alfa«, Margarinefabrikken, A.-S., Margarinefabrikation, Vejen 1161—62, 1192 94 Almindelige Handelskompagni, Det, A.-S., Handel, København 1094 Alstrup, J. A., A.-S., Handel, Aarhus 510 Aluminium -Indu^trie-Aktiengesellschaft, Fabrikation og Handel med kemiske Produkter, Neuhausen 1046 Aluminum Company of America, Metalvarefabrikation, Pittsburgh 369 Amanti, Aktiebolaget, f. d. A.-B. Bernhard Maring, Fabrikation og Handel med kemisk tekniske Præparater, Stockholm 427 Amber Size & Chemical Company, The, Limited, Fabrikation af kemiske Præparater, London 426 American Laundry Machinery Company, The, Fabrikation, Cincinnati 1357 American Rolling Mill Company, The, Fabrikation, Middletown i Ohio 933 American Tobacco Co., The, A.-S., Tobaksvarefabrikation, København 305, 367, 584, 757, • 1100, 1148, 1189—90, 1212, 1323, 1345 Amiesite Asphalt, Ltd., Handel, Montreal ø5 Andersen, A., Firmaet, Frugthandel, København 666 , Andreas, & Olsen, Handel med Herrehatte Samt Fabrikation af Huer og Kasketter, København 1331 , Axel, Smørfabrikation, Aarhus 45g , Emil, Firmaet, Handel med Mel m. -

Martian Crater Morphology

ANALYSIS OF THE DEPTH-DIAMETER RELATIONSHIP OF MARTIAN CRATERS A Capstone Experience Thesis Presented by Jared Howenstine Completion Date: May 2006 Approved By: Professor M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Professor Christopher Condit, Geology Professor Judith Young, Astronomy Abstract Title: Analysis of the Depth-Diameter Relationship of Martian Craters Author: Jared Howenstine, Astronomy Approved By: Judith Young, Astronomy Approved By: M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Approved By: Christopher Condit, Geology CE Type: Departmental Honors Project Using a gridded version of maritan topography with the computer program Gridview, this project studied the depth-diameter relationship of martian impact craters. The work encompasses 361 profiles of impacts with diameters larger than 15 kilometers and is a continuation of work that was started at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas under the guidance of Dr. Walter S. Keifer. Using the most ‘pristine,’ or deepest craters in the data a depth-diameter relationship was determined: d = 0.610D 0.327 , where d is the depth of the crater and D is the diameter of the crater, both in kilometers. This relationship can then be used to estimate the theoretical depth of any impact radius, and therefore can be used to estimate the pristine shape of the crater. With a depth-diameter ratio for a particular crater, the measured depth can then be compared to this theoretical value and an estimate of the amount of material within the crater, or fill, can then be calculated. The data includes 140 named impact craters, 3 basins, and 218 other impacts. The named data encompasses all named impact structures of greater than 100 kilometers in diameter. -

Towards an Improved Morphometric Database of Valleys and Fans on Mars

52nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 2021 (LPI Contrib. No. 2548) 2084.pdf TOWARDS AN IMPROVED MORPHOMETRIC DATABASE OF VALLEYS AND FANS ON MARS. D. C. A. Silva 1, D. A. Vaz 1,2 , G. Di Achille 2, 1CITEUC, Centre for Earth and Space Research of the University of Coimbra, Observatório Astronómico da Universidade de Coimbra, Almas de Freire, 3040-004 Coimbra, Portugal ([email protected]) , 2INAF - Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica, Osservatorio Astronomico d’Abruzzo, Via Mentore Maggini, 64100 Teramo TE, Italy. Introduction: Martian fan-shaped deposits have included in the database. New deposits will also be been the subject of study for their presumed deltaic surveyed where new CTX data is available. origin, which is thought as a good indicator on how the In order to constrain the age of the deposits we will atmospheric conditions and climate evolved on Mars perform crater-counts for each study area. The overall [1-3]. Therefore, the study of these deposits constitutes age distribution of the fans will be appraised, aiming to one of the few ways to constrain the amount of water test a possible dual formation age scenario that existed on the surface, providing valuable hypothesized in [7]. Mineralogical and thermal-inertia indications regarding the paleoenvironmental summary data will be integrated in the database, conditions. However, these deposits present a large providing additional constrains on the interpreted morphological diversity suggesting different depositional environments and subsequent post- depositional settings. depositional evolution. In [4] is argued that two different types of Finally, this updated global database will be depositional fans are present on the Martian surface. -

Death Certificates 1903-1958

Yamhill County Death Certificate Index Index to Death Certificates at the Yamhill County Historical Society Research Library in Lafayette, Oregon 1903 through 1958 Yamhill County Historical Society 657 Market Street Lafayette, Oregon 97127 www. yamhillcountyhistory.org 1 Death certificates are a mix of originals and some photocopies. Index accuracy is challenged by interpretation of handwriting, and the accuracy of the original transcriber. Copies can be obtained by contacting us at by phone or email, or in person during our open hours. Current contact information can be found at www.yamhillcountyhistory.org A duplication fee will be incurred for copies made. 2 YAMHILL COUNTY DEATH CERTIFICATES ALPHABETICAL Num Snum Lnum Death Last First Middle Middle2 Title 8425 127 6 02 Mar 1943 Aaron George Washington 7317 114 16 09 Jun 1939 Aaron Sabina Barnett 7449 246 162 28 Nov 1939 Abbey David James 8072 32 19 06 Feb 1942 Abbey Mary Josephine 12787 4897 18 18 Apr 1948 Abderhalden Abraham 10767 6285 76 19 May 1951 Abderhalden Sarah Earl 1823 82 3 20 May 1916 Abdil Lloyd 3620 48 22 Feb 1925 Abdill Charlot Gibbon 6272 235 139 25 Nov 1935 Abdill Daniel B 4841 79 43 13 Mar 1930 Abdill George Brezette 5247 231 148 21 Dec 1931 Abdill William Flemming 213 401 05 Feb 1906 Abel Emma 3944 150 01 Sep 1926 Abel Jennie 4375 109 08 Jun 1928 Abel John Henry 4560 63 24 Mar 1929 Abernathy Adelein E 5681 161 21 Aug 1933 Abernathy George Elwood 13130 1374 6 16 Feb 1945 Abernathy Roy 8782 133 42 09 May 1944 Abner Mary Belle 13193 6145 16 17 Sep 1945 Abraham Richard -

Appendix I Lunar and Martian Nomenclature

APPENDIX I LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE A large number of names of craters and other features on the Moon and Mars, were accepted by the IAU General Assemblies X (Moscow, 1958), XI (Berkeley, 1961), XII (Hamburg, 1964), XIV (Brighton, 1970), and XV (Sydney, 1973). The names were suggested by the appropriate IAU Commissions (16 and 17). In particular the Lunar names accepted at the XIVth and XVth General Assemblies were recommended by the 'Working Group on Lunar Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr D. H. Menzel. The Martian names were suggested by the 'Working Group on Martian Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr G. de Vaucouleurs. At the XVth General Assembly a new 'Working Group on Planetary System Nomenclature' was formed (Chairman: Dr P. M. Millman) comprising various Task Groups, one for each particular subject. For further references see: [AU Trans. X, 259-263, 1960; XIB, 236-238, 1962; Xlffi, 203-204, 1966; xnffi, 99-105, 1968; XIVB, 63, 129, 139, 1971; Space Sci. Rev. 12, 136-186, 1971. Because at the recent General Assemblies some small changes, or corrections, were made, the complete list of Lunar and Martian Topographic Features is published here. Table 1 Lunar Craters Abbe 58S,174E Balboa 19N,83W Abbot 6N,55E Baldet 54S, 151W Abel 34S,85E Balmer 20S,70E Abul Wafa 2N,ll7E Banachiewicz 5N,80E Adams 32S,69E Banting 26N,16E Aitken 17S,173E Barbier 248, 158E AI-Biruni 18N,93E Barnard 30S,86E Alden 24S, lllE Barringer 29S,151W Aldrin I.4N,22.1E Bartels 24N,90W Alekhin 68S,131W Becquerei -

IZW Jahresbericht 2016 Leibniz-Institut Für Zoo- Und Wildtierforschung IZW Jahresbericht 2016 IZW Jahresbericht Im Forschungsverbund Berlin E.V

Copyright 2016: Leibniz-Institut für Zoo- und Wildtierforschung (IZW) IZW Jahresbericht 2016 Leibniz-Institut für Zoo- und Wildtierforschung IZW Jahresbericht 2016 IZW Jahresbericht im Forschungsverbund Berlin e.V. Titelfoto: Nabire eines der letzten Nördlichen Breitmaulnashörner (Ceratotherium simum cottoni) verstarb im Juli 2015. Joel Sartore/ ZOO Dvůr Králové. Forschung für den Artenschutz: Rettungsplan für das Breitmaulnashorn Auf der ganzen Welt gibt es nur noch drei Individuen des Nördlichen Breitmaulnashorns. Alle drei Tie- re sind auf natürlichem Weg nicht mehr fortpflanzungsfähig. Unter der Leitung des IZW entwickelte ein internationales Wissenschaftlerteam einen Rettungsplan. Ziel ist es, mithilfe von mondernsten Methoden der assistieren Reproduktion und der Stammzellforschung Nachwuchs zu erzeugen. Publikation: Saragusty J, Diecke S, Drukker M, Durrant B, Friedrich Ben-Nun I, Galli C, Göritz F, Hayashi K, Hermes R, Holtze S, Johnson S, Lazzari G, Loi P, Loring JF, Okita K, Renfree MB, Seet S, Voracek T, Stejskal J, Ryder OA, Hildebrandt TB (2016): Rewinding the process of mammalian extinction. ZOO BIOL 35, 280- 292. doi:10.1002/zoo.21284. S Friedrichsfelde Ost N Alt-Friedrichsfelde B1/ B5 Berlin-Zentrum Frankfurt/Oder Einbeckerstraße Impressum U Friedrichsfelde Zachertstraße Alfred-Kowalke-Straße Titel: Jahresbericht 2016: Leibniz-Institut für Zoo- und Wildtierforschung (IZW) Leibniz-Institut für Zoo- und Wildtierforschung IZW im Forschungsverbund Berlin e.V. :: Forschung für den Artenschutz :: Straße Alfred-Kowalke-Str. 17, 10315 Berlin Herausgeber: Leibniz-Institut für Zoo- und Wildtierforschung Am Tierpark/ im Forschungsverbund Berlin e.V. Alfred-Kowalke-Str Standort: Alfred-Kowalke-Straße 17, 10315 Berlin Rummelsburger (am Tierpark Berlin-Friedrichsfelde) Postalisch: Postfach 70 04 30, 10324 Berlin Am ierpark Tel.: + (49)- 30 - 51 68-0 T So erreichen Sie das IZW: Fax: + (49)- 30 - 51 26-104 Internet: http://www.leibniz-izw.de Tierpark Berlin ISSN: 1661-0208 U5 Bhf. -

XV Congresso Nazionale Di Scienze Planetarie PRESIDENTE DEL CONGRESSO: Giovanni Pratesi

https://doi.org/10.3301/ABSGI.2019.01 Firenze, 4-8 Febbraio 2019 ABSTRACT BOOK a cura della Società Geologica Italiana XV Congresso Nazionale di Scienze Planetarie PRESIDENTE DEL CONGRESSO: Giovanni Pratesi. COMITATO SCIENTIFICO: Giovanni Pratesi, Emanuele Pace, Marco Benvenuti, John Brucato, Fabrizio Capaccioni, Sandro Conticelli, Aldo Dell’Oro, Carlo Alberto Garzonio, Daniele Gardiol, Monica Lazzarin, Alessandro Marconi, Lucia Mari- nangeli, Giuseppina Micela, Ettore Perozzi, Alessandro Rossi, Alessandra Rotundi. COMITATO ORGANIZZATORE: Cristian Carli, Mario Di Martino, Livia Giacomini, Vanni Moggi Cecchi, Emanuele Pace, Giovanni Pratesi, Giovanni Valsecchi. CURATORI DEL VOLUME Giovanni Pratesi, Fabrizio Capaccioni, Emanuele Pace, John Brucato, Marco Benvenuti, Sandro Conti- celli, Aldo Dell’Oro, Daniele Gardiol, Carlo Alberto Garzonio, Monica Lazzarin, Alessandro Marconi, Lucia Marinangeli, Giuseppina Micela, Ettore Perozzi, Alessandro Rossi, Alessandra Rotundi. Papers, data, figures, maps and any other material published are covered by the copyright own by the Società Geologica Italiana. DISCLAIMER: The Società Geologica Italiana, the Editors are not responsible for the ideas, opinions, and contents of the papers published; the authors of each paper are responsible for the ideas opinions and con- tents published. La Società Geologica Italiana, i curatori scientifici non sono responsabili delle opinioni espresse e delle affermazioni pubblicate negli articoli: l’autore/i è/sono il/i solo/i responsabile/i. ABSTRACT INDEX EDUCARE ALLA -

Sammenrediert Rsmelding 2006

Årsmelding Norsk kulturråd 2006 Årsmelding Norsk kulturråd 2006 ........................................................................................... 1 Innledning .............................................................................................................................. 3 Råd og utvalg .......................................................................................................................... 4 Norsk kulturfond ................................................................................................................. 7 Hovedfordeling av Norsk kulturfond 2006 .................................................................................... 8 Oversikt over søknader 2006 ..................................................................................................... 8 Statistikk ................................................................................................................................9 Fylkesvise fordelinger i 2006.....................................................................................................11 Forholdet mellom antall søknader og tildelinger fordelt på fylker i 2006...........................................12 Administrasjonsutgifter........................................................................................................13 Driftsutgifter ..........................................................................................................................13 Inntekter ...............................................................................................................................13 -

Sustainable Mars Sample Return

• ',- Sustainable Mars Sample Return ODU Mars Sample Return Team: Old Dominion University Submission ID: kYIRn Christie Alston Sean Hancock Joshua Laub Christopher Perry Faculty Advisor: Dr. Robert Ash C.J • ABSTRACT The proposed Mars sample return mISSIon will be completed using natural Martian resources for the majority of its operations. The system uses the following technologies: In-Situ Propellant Production (ISPP), a methane-oxygen propelled Mars Ascent Vehicle (MAV), a carbon dioxide powered hopper, and a hydrogen fueled balloon system (large balloons and small weather balloons). The ISPP system will produce the hydrogen, methane, and oxygen using a Sabatier reactor. a water electrolysis cell, water extracted from the Martian surlace, and carbon dioxide extracted from the Martian atmosphere. Indigenous hydrogen will fuel the balloon systems and Iocally-dclivcd methane and oxygen will fuel the MAV for the return of a 50 kg sample to Earth. The ISPP system will have a production cycle of 800 days and the estimated overall mission length is 1355 days from Earth departure to return to low Earth orbit. Combining these advanced technologies will enable the proposed sample return mission to be executed with reduced initial launch mass and thus be more cost efficient. The successful completion of this mission will serve as the next step in the advancement of Mars exploration technology. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 PURPOSE ~ 5 CONCEPT OF OPERATIONS 5 LANDING SITE SELECTION 7 OPERATING ENVIRONMENT 11 SURFACE OPERATIONS SYSTEM OVERVIEW -

EGU2016-12696, 2016 EGU General Assembly 2016 © Author(S) 2016

Geophysical Research Abstracts Vol. 18, EGU2016-12696, 2016 EGU General Assembly 2016 © Author(s) 2016. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Sedimentology and hydrology of a well-preserved paleoriver systems with a series of dam-breach paleolakes at Moa Valles, Mars Francesco Salese (1), Gaetano Di Achille (2), Adrian Neesemann (3), Gian Gabriele Ori (1,4), and Ernst Hauber (5) (1) International Research School of Planetary Sciences, Dipartimento di Ingegneria e Geologia, Università Gabriele D’Annunzio, Viale Pindaro 42, 65127 Pescara, Italy, (2) Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica, Osservatorio Astronomico di Teramo (INAF-OATe), Via Mentore Maggini snc, 64100 Teramo, Italy, (3) Freie Universität Berlin, Institute of Geological Sciences, Planetary Sciences and Remote Sensing, Malteserstr. 74-100, 12249 Berlin, Germany, (4) Ibn Battuta Centre, Université Cady Ayyad, Av. Prince Moulay Abdellah, Marrakech, Morocco, (5) Institute of Planetary Research, German Aerospace Center, Rutherfordstrasse 2, DE-12489 Berlin, Germany Moa Valles is a well-preserved paleodrainage system that is nearly 300-km-long and carved into ancient highland terrains west of Idaeus Fossae. The paleofluvial system apparently originated from fluidized ejecta blankets, and it consists of a series of dam-breach paleolakes with associated fan-shaped sedimentary deposits. This paleofluvial system shows a rich morphological record of hydrologic activity in the highlands of Mars. Based on crater counting the latter activity seems to be Amazonian in age (2.43 - 1.41 Ga). This work is based on a digital elevation model (DEM) derived from Context camera (CTX) and High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) stereo images. Our goals are to (a) study the complex channel flow paths draining into Idaeus Fossae after forming a series of dam-breach paleolakes and to (b) investigate the origin and evolution of this valley system with its implications for climate and tectonic control. -

General Disclaimer One Or More of the Following Statements May Affect

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=19680018720 2020-03-12T10:00:05+00:00Z General Disclaimer One or more of the Following Statements may affect this Document This document has been reproduced from the best copy furnished by the organizational source. It is being released in the interest of making available as much information as possible. This document may contain data, which exceeds the sheet parameters. It was furnished in this condition by the organizational source and is the best copy available. This document may contain tone-on-tone or color graphs, charts and/or pictures, which have been reproduced in black and white. This document is paginated as submitted by the original source. Portions of this document are not fully legible due to the historical nature of some of the material. However, it is the best reproduction available from the original submission. Produced by the NASA Scientific and Technical Information Program ·• NASA TECHNICAL NASA TR R-277 REPORT < V, < z: CHRONOLOGICAL CATALOG OF REPORTED LUNAR EVENTS by Barbara M. Middlehurst University of Arizona Jaylee M. Burley Goddard Space Flight Center Patrick Moore Armagh Planetarium and Barbara L. Welther Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION • WASHINGTON, D. C. • JULY 1968 NASA TR R-277 CHRONOLOGICAL CATALOG OF REPORTED LUNAR EVENTS By Barbara M. Middlehurst University of Arizona Tucson, Ariz. Jaylee M. Burley Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Md. Patrick Moore Armagh Planetarium Armagh, Northern Ireland and Barbara L. Welther Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory Cambridge, Mass. NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION For sale by the Clearinghouse for Federal Scientific and Technical Information Springfield, Virginia 22151 - CFSTI price $3.00 ABSTRACT A catalog of reports of lunar events, or temporary changes on the moon, has been compiled based on literature covering more than four centuries. -

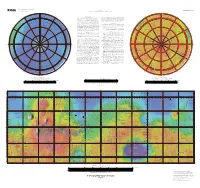

Topographic Map of Mars

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR OPEN-FILE REPORT 02-282 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Prepared for the NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION 180° 0° 55° –55° Russell Stokes 150°E NOACHIS 30°E 210°W 330°W 210°E NOTES ON BASE smooth global color look-up table. Note that the chosen color scheme simply 330°E Darwin 150°W This map is based on data from the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA) 30°W — 60° represents elevation changes and is not intended to imply anything about –60° Chalcoporous v (Smith and others 2001), an instrument on NASA’s Mars Global Surveyor Milankovic surface characteristics (e.g. past or current presence of water or ice). These two (MGS) spacecraft (Albee and others 2001). The image used for the base of this files were then merged and scaled to 1:25 million for the Mercator portion and Rupes map represents more than 600 million measurements gathered between 1999 1:15,196,708 for the two Polar Stereographic portions, with a resolution of 300 and 2001, adjusted for consistency (Neumann and others 2001 and 2002) and S dots per inch. The projections have a common scale of 1:13,923,113 at ±56° TIA E T converted to planetary radii. These have been converted to elevations above the latitude. N S B LANI O A O areoid as determined from a martian gravity field solution GMM2 (Lemoine Wegener a R M S s T u and others 2001), truncated to degree and order 50, and oriented according to IS s NOMENCLATURE y I E t e M i current standards (see below).